Everyone Has the Right to Rest on Their Sabbath

Remembering when Joe Lieberman intervened in support of a Sunday-observing Presbyterian

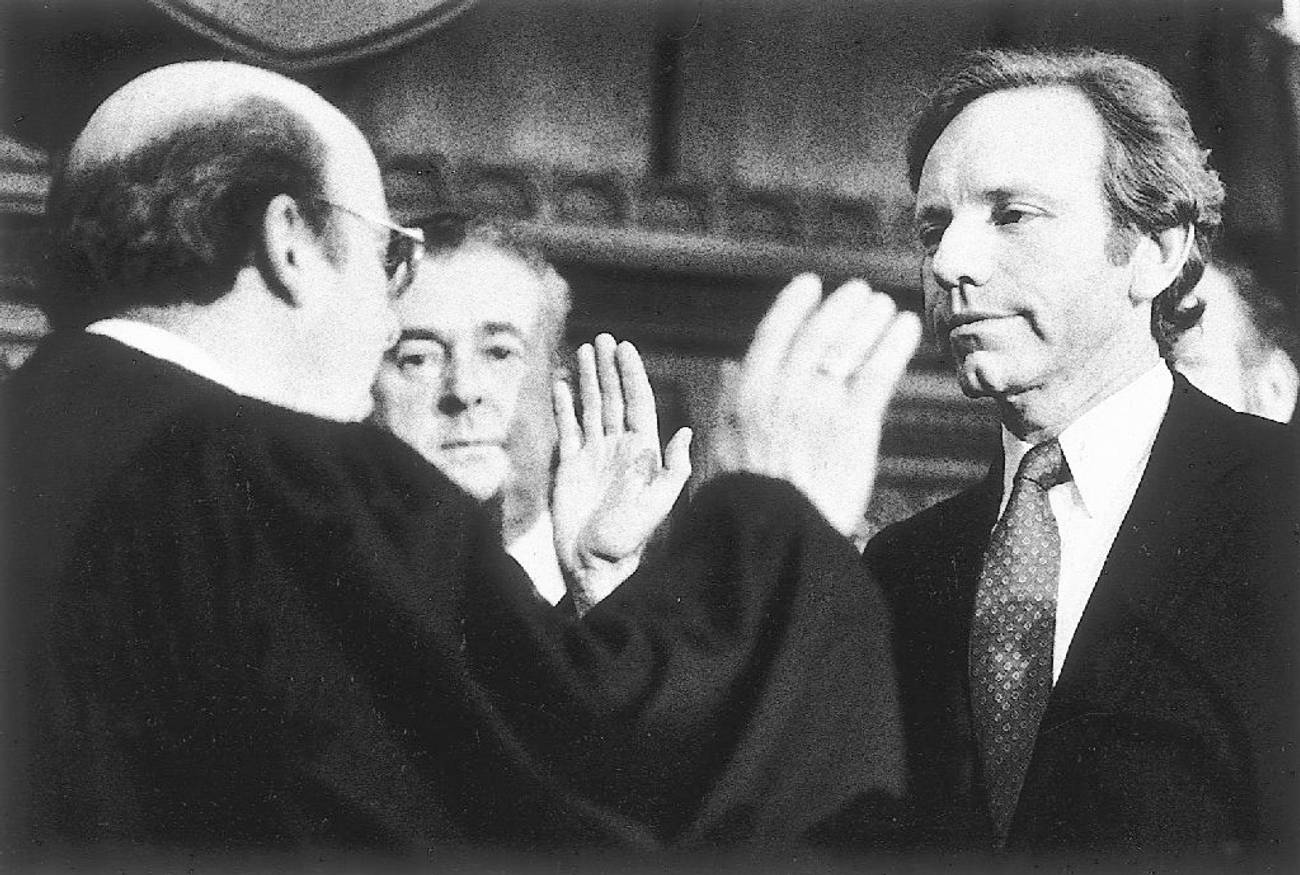

Tribune News Service via Getty Images via Getty Images

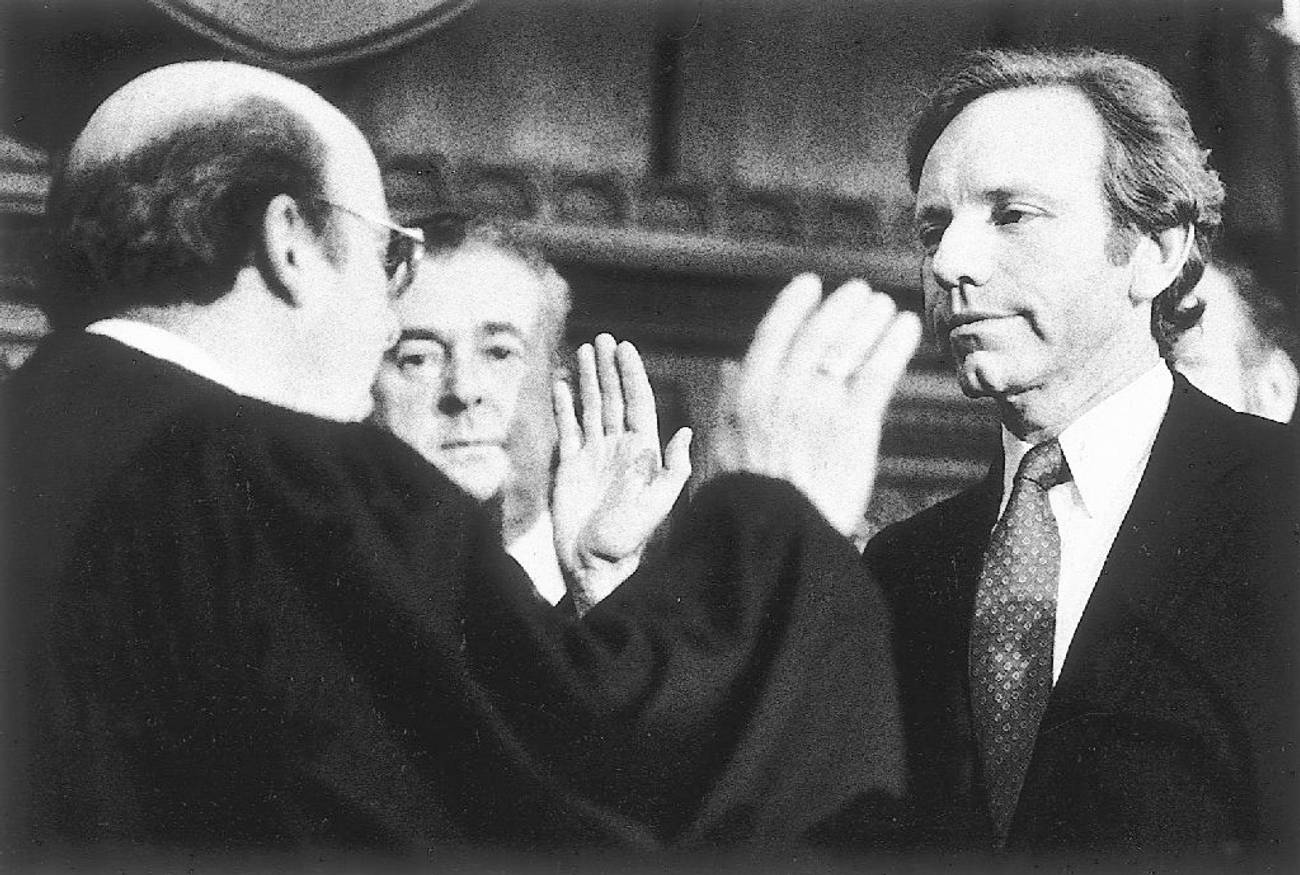

Tribune News Service via Getty Images via Getty Images

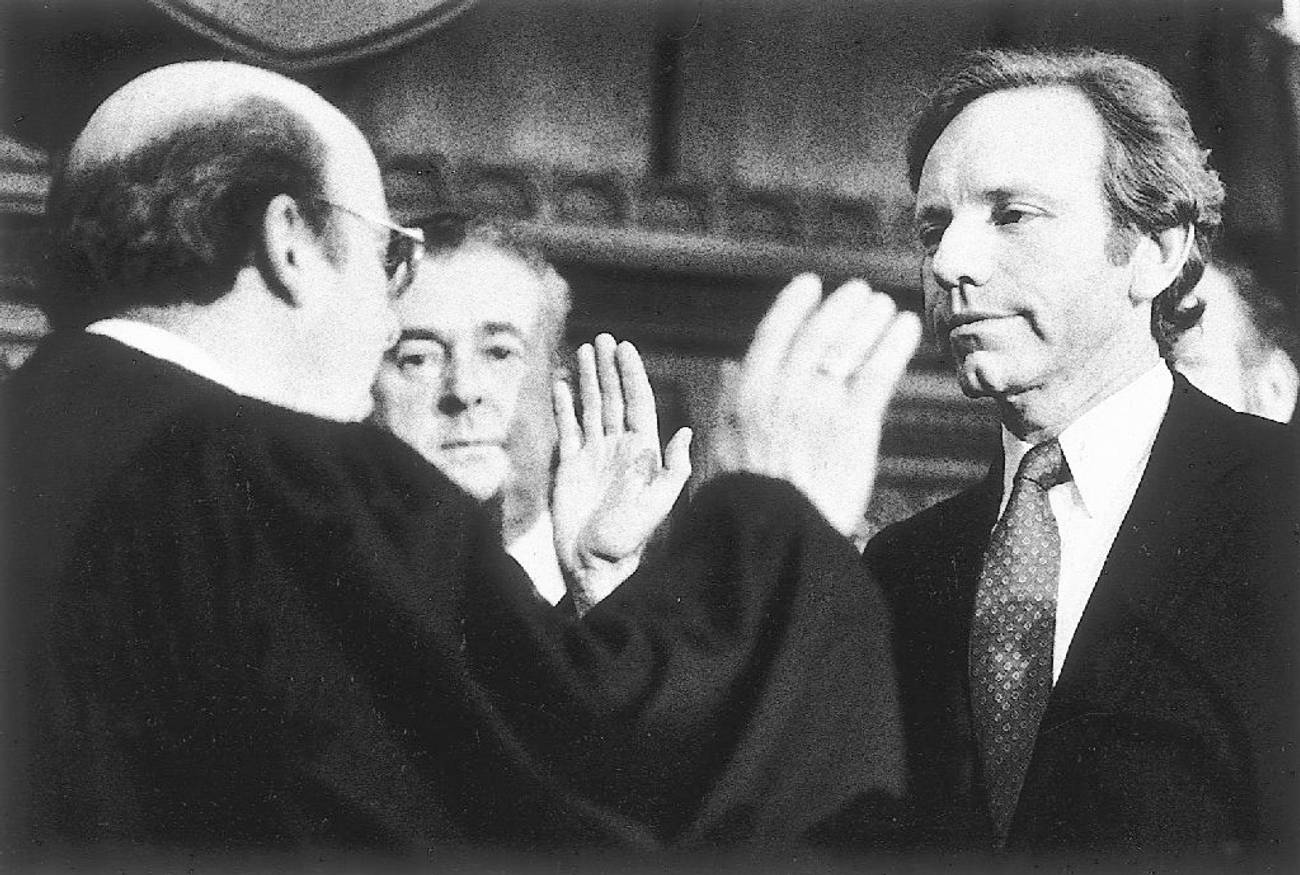

Tribune News Service via Getty Images via Getty Images

“Do you know that Connecticut recently elected a Jewish Sabbath-observing attorney general?” That question was put to me in January 1984 after I filed a petition asking the Supreme Court to review a Connecticut Supreme Court decision that had invalidated, on federal constitutional grounds, a law that declared, “No person who states that a particular day of the week is observed as his Sabbath may be required by his employer to work on such day.” The court reasoned that the word “Sabbath” was not “devoid of religious overtones” so that the day specified in the law “comes with religious strings attached.” The Connecticut court concluded that this invalidated the law under the First Amendment’s clause prohibiting an establishment of religion.

The case had been brought by a Sunday-observing Presbyterian named Donald Thornton, who had been employed by a Caldor department store. When Connecticut repealed its compulsory Sunday closing laws, Thornton was assigned to work on Sunday. He refused, was fired, and filed a lawsuit citing the law that had been passed to mitigate the effect of the new law enacted to accommodate religious employees.

I read the Connecticut decision and called his lawyer to notify him that I would be preparing an amicus curiae (friend-of-the-court) brief on behalf of the Orthodox Jewish community to support the request to the U.S. Supreme Court that he would surely make. The lawyer replied that Thornton had died while his lawsuit was pending and that his widow would not pay for further litigation. I volunteered to represent Thornton’s estate in the Supreme Court pro bono to get the horrendous ruling vacated. Thornton’s widow officially designated me as the estate’s lawyer.

Joe Lieberman’s personal decision to inject the state into the case was a seed of the independence and candor that marked his future public career.

The state of Connecticut had not defended the law’s constitutionality when it was challenged in the state’s highest court. I did not know whether it would officially defend the law before the U.S. Supreme Court. I was, of course, eager to enlist Connecticut on my side. So I called the relatively new religiously observant attorney general to ask him to file a friend-of-the-court brief supporting my request that the court hear the case.

That is how I first met Joe Lieberman. He had been elected attorney general of Connecticut in 1983.

Joe expressed surprise when I informed him of the decision of Connecticut’s Supreme Court. No local law or procedure required notification to the attorney general when the constitutionality of a duly enacted statute was challenged in court. Connecticut’s Supreme Court had voided the law without asking the state’s highest legal officer to weigh in.

Lieberman responded sympathetically to my request but added his personal belief that the state should be more than a friend of the court. It should, he said, be a party to the litigation. He intended to file a motion in the Supreme Court requesting formal “intervention” as a party.

Invoking my years of experience as a former Supreme Court law clerk and, by then, frequent litigator in the Supreme Court, I confidently told Joe that he was too late. “The time to intervene was when the case was in the Connecticut courts. The Supreme Court does not allow intervention if it is first requested when a case comes before it.”

Joe brushed off my admonition. He filed a request that the state of Connecticut be permitted to intervene and a brief supporting Thornton’s refusal to work on Sundays. Our constitutional defense of the law and my request for review were also supported by the U.S. Department of Justice, speaking through Solicitor General Rex Lee and his assistant, a young lawyer named Michael McConnell (who went on to become the nation’s foremost legal authority on church-state law and a celebrated federal judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit).

Seeking to trivialize the case, Caldor told the Supreme Court that “nobody seems to know from whence this statute came” and that “this odd statute and odd factual situation is designed for consideration by moot courts and not by the Supreme Court of the United States.” But the case fascinated the justices. The files of Justice Harry Blackmun are publicly accessible in the Library of Congress. His law clerks’ memoranda recommended that the court agree to hear the case, and Blackmun’s own handwritten notes reveal the puzzling legal issues they saw.

The court agreed to take the case and, disproving my confident expert opinion, it granted Joe’s request to intervene. He and I filed briefs, and on the afternoon of Wednesday, Nov. 7, 1984, we both sequentially presented oral argument.

Justice Blackmun customarily took handwritten contemporaneous notes during oral argument. He would assign a numerical grade to the advocates’ performance and would identify the lawyers by age and by the law school they had attended. At times, he would note a physical characteristic. (I had started growing a beard shortly before the Thornton argument, and Blackmun’s handwritten note has my name, that I was then 48, and “beard now.”) Blackmun’s personally written notes reveal an idiosyncratic interest in the Jewish identity of counsel. When Blackmun believed that a lawyer was Jewish, he would put a capital letter “J” on the identifying line. His notes of Lieberman’s oral argument read, “blond,” 42, and “no look J.”

Joe opened his oral argument as follows:

As Attorney General of Connecticut, I am particularly troubled by the decision of our supreme court in this case, because of the message that it gives to our legislature, which is that any act that it may choose to adopt which gives special benefit or recognition to religious observance like the observance of the Sabbath is automatically unconstitutional. That is clearly not the message that this Court has given.

This Court has repeatedly warned against absolute and inflexible application of the establishment clause which would lead to mechanically invalidating any law that recognized religious observance in any particular way.

Representing the state of Connecticut, Joe told the court that the agency enforcing the law “quite clearly read it as not being absolute.” The court did not issue a decision in the case until late June, when it decided by an 8-to-1 vote to declare the Connecticut law unconstitutional in a short opinion by Chief Justice Burger because—ignoring the Connecticut attorney general’s authoritative pronouncement—Burger said it “provides Sabbath observers with an absolute and unqualified right not to work on their Sabbath.”

Joe Lieberman’s stint as Connecticut’s attorney general is a blip in his lifetime of personal courage and accomplishment on behalf of the United States, the Jewish people, and Israel. But his personal decision to inject the state into the case of a deceased Sunday-observing Presbyterian and the dismay he expressed, as he opened his oral argument, over the intolerant message that the state court’s decision conveyed to the state legislature were seeds of the independence and candor that marked his future public career. It was, unfortunately, not the only time in years of public advocacy that other authoritative voices failed to heed his words.

And, as all his biographers note, he was the quintessential American exemplifying the many who “stated that a particular day of the week is observed as his Sabbath.”

Nathan Lewin is a Washington, D.C., lawyer with a Supreme Court practice who has also taught as an adjunct professor at Harvard, Georgetown, Columbia, and University of Chicago law schools.