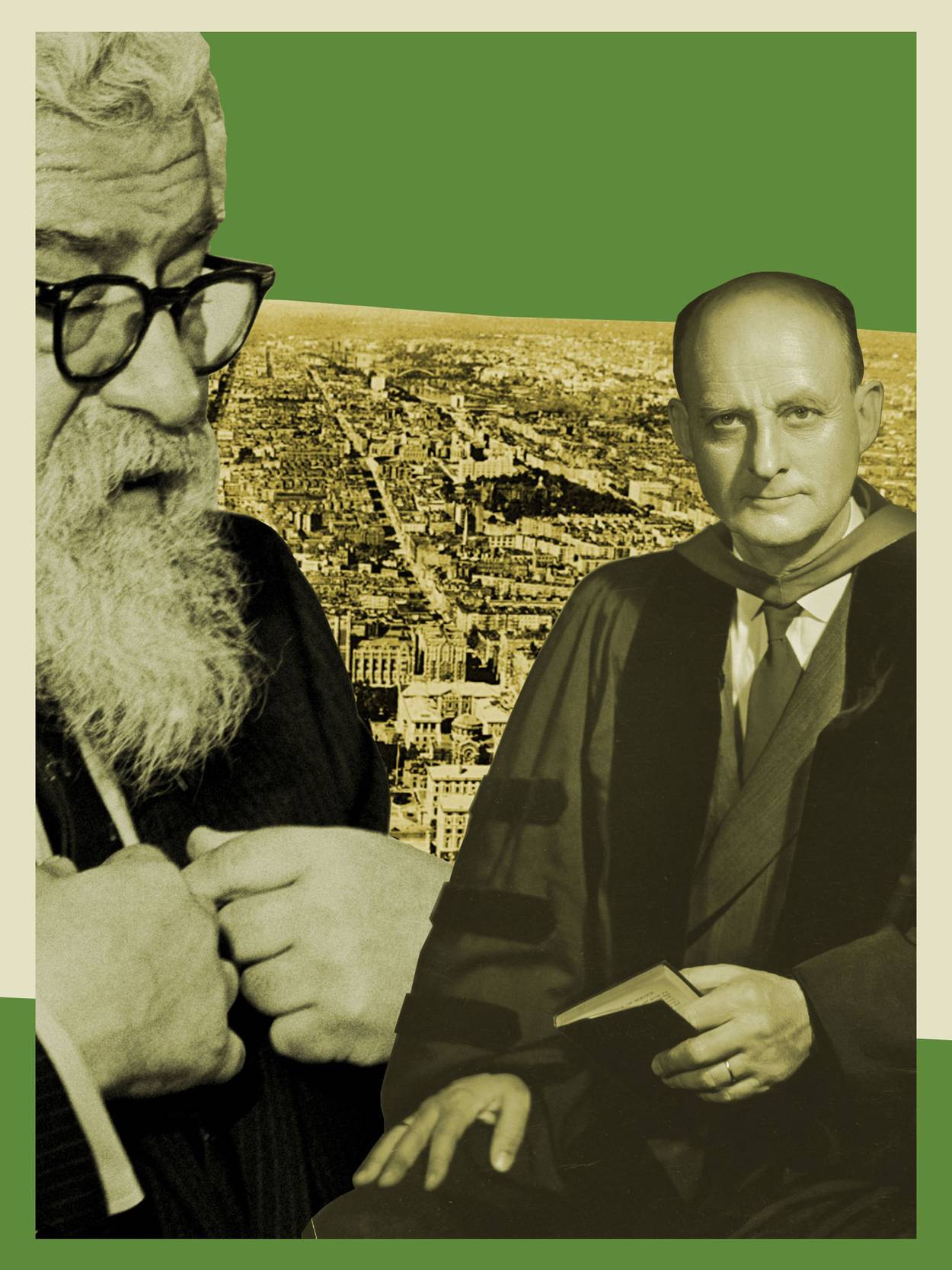

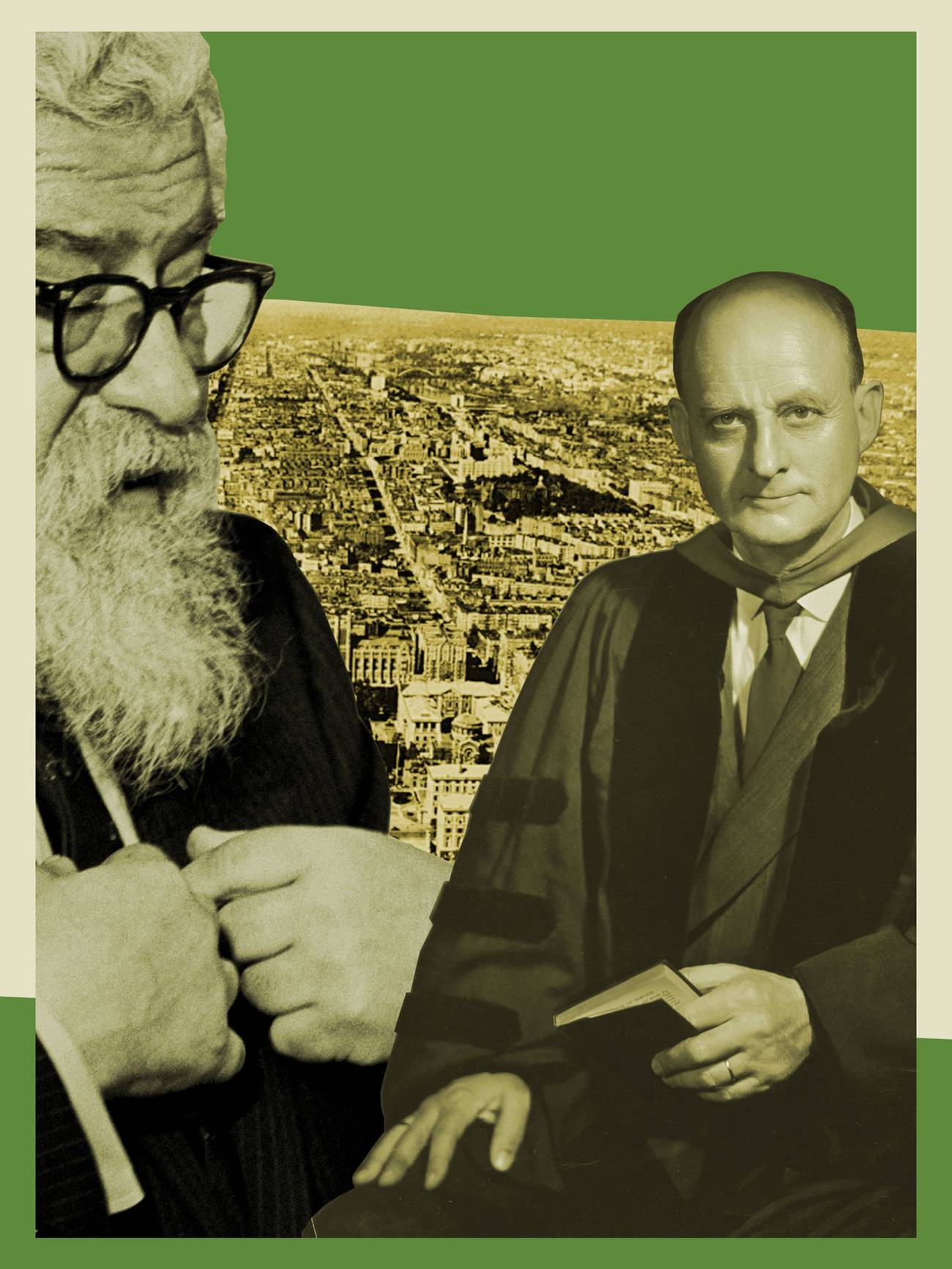

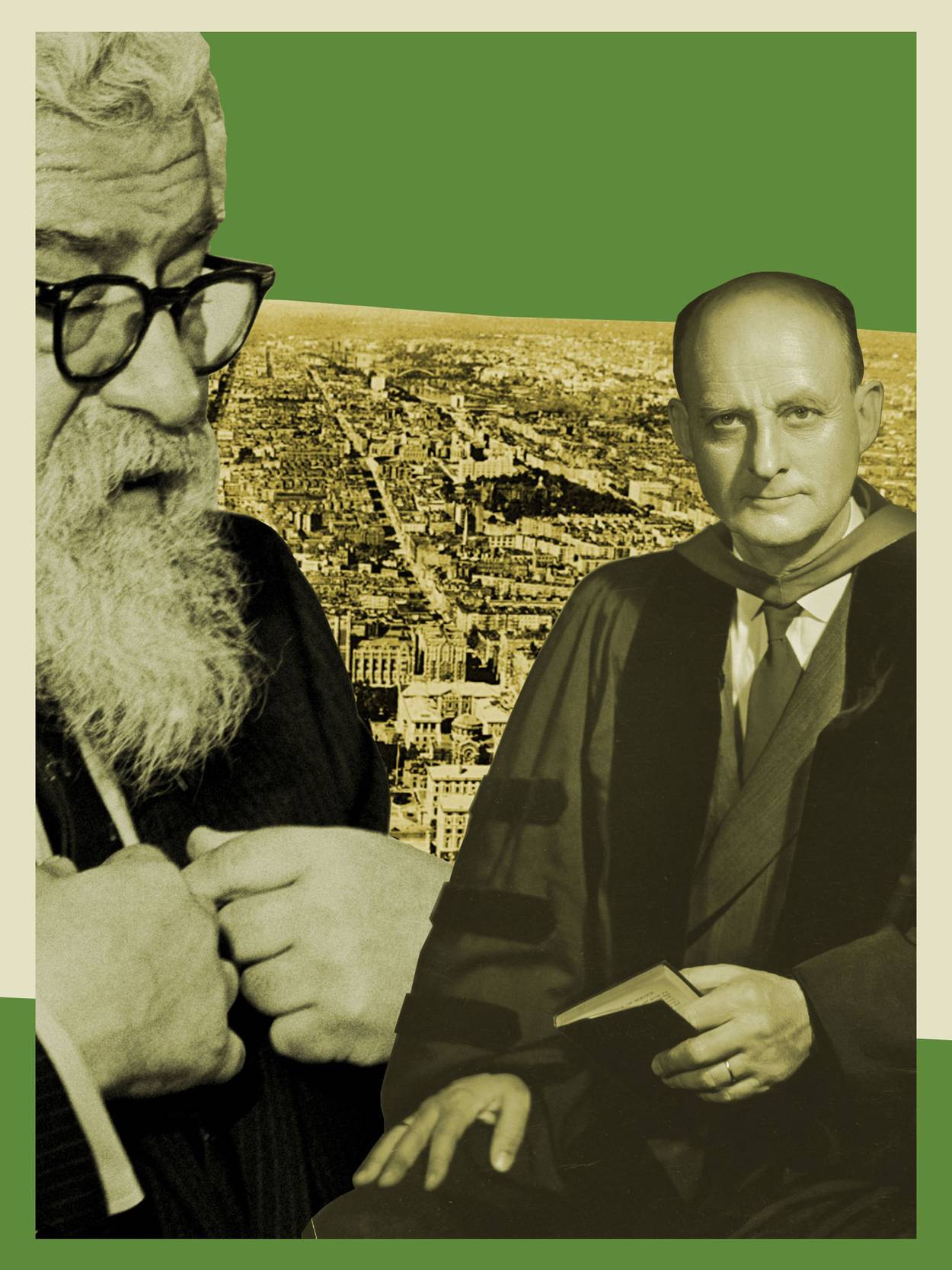

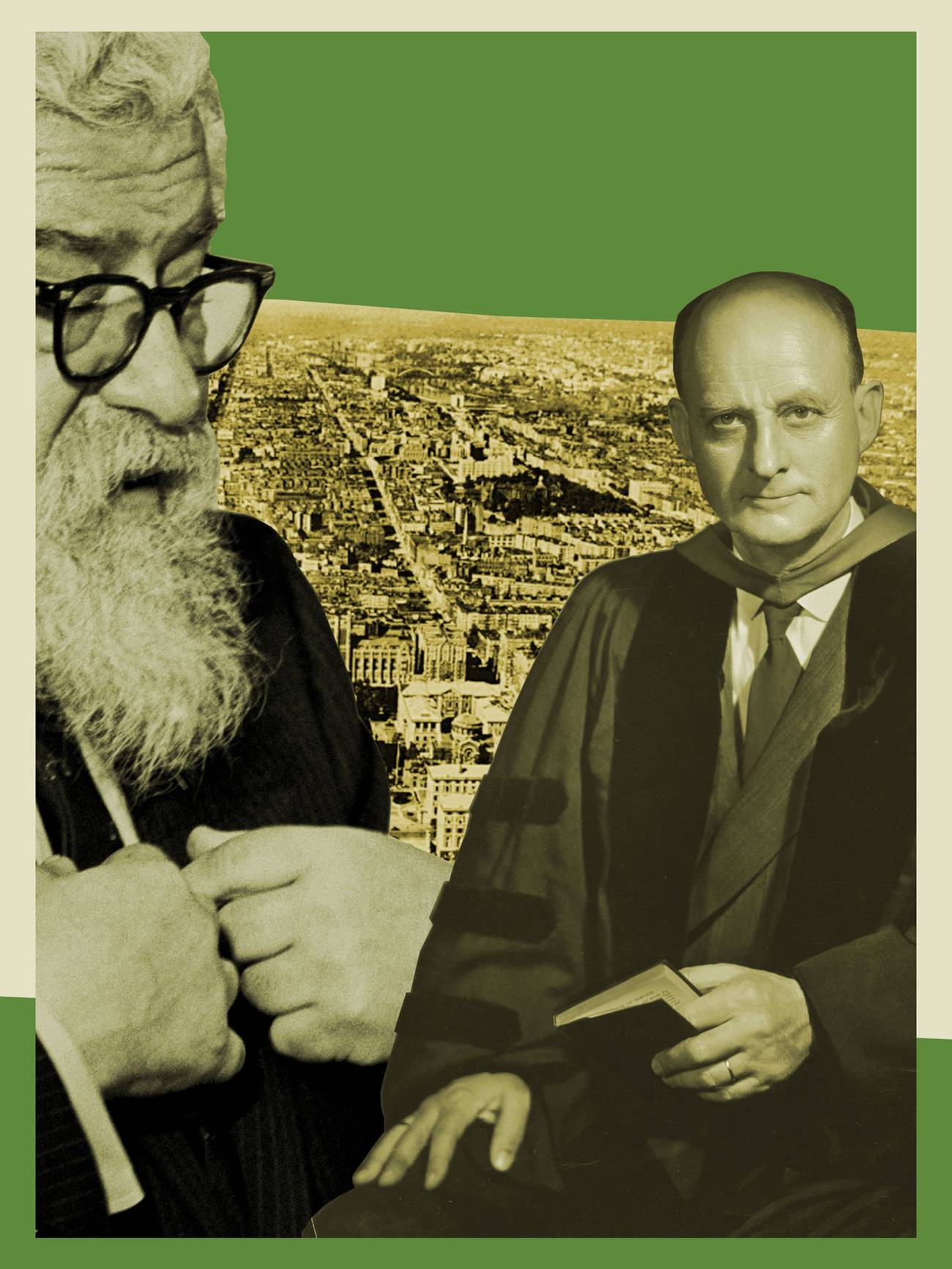

When a Broader Religious Pluralism Began to Flower

The impact of Abraham Joshua Heschel and Reinhold Niebuhr on post-WWII America

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971) and Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-72) were two of the greatest American religious figures of the last century—as well as unlikely friends.

Niebuhr’s sometimes controversial emphasis on the limitations in human nature was widely influential among groups as diverse as religious scholars and foreign policy strategists. His resulting Serenity Prayer, asking God to grant us serenity for things we can’t change, courage to change what we can and should change, and wisdom to know the difference, has been popular for decades as a day-at-a-time recipe for living.

Niebuhr’s influence has declined slightly since his death, whereas Heschel’s has increased. Heschel’s stand-out, passionate embrace of the Civil Rights movement and his friendship with Martin Luther King Jr., also somewhat controversial then, are uniformly celebrated today. And his spiritual orientation has attracted an interfaith audience across the religious spectrum.

Heschel was a leading Jewish theologian who said he sometimes thought Christians understood him better than Jews did. Niebuhr, one of the 20th century’s dominant Protestant theologians, had some interesting Jewish affinities, such as a steady focus on the Hebrew prophets.

Niebuhr grew up speaking German, and initially pastored German-speaking immigrant congregations in the Midwest. Heschel, though originally from a Hasidic dynasty in Poland, lived and taught in Germany, and wrote his doctoral dissertation in German. But that did not prevent his mother and three sisters from being killed during the Holocaust. And yet, remarkably, shortly before he died, Niebuhr chose Heschel to deliver the only eulogy at his funeral—despite a heritage that was very different from Heschel’s and despite Niebuhr’s worldwide prominence among Protestants.

The unexpected closeness between Niebuhr and Heschel is partially explained by not-always-obvious similarities between them, such as each being the son of a cleric and each striving to move beyond a provincial upbringing. The easiest similarity to decipher was physical proximity: Heschel taught for two decades at the Jewish Theological Seminary on the Upper West Side of Manhattan near Columbia University. Niebuhr taught for more than three decades at Union Theological Seminary, situated on the very next block diagonally across Broadway from JTS. The area is called Seminary Row, and each became perhaps the most famous teacher at his respective institution.

Two other similarities deserve greater attention; first, the ways in which both thinkers flourished in an American religious environment that seems quite different from our own, and second, the contributions of both theologians to a broader American religious pluralism at a time when it was only beginning to fully flower.

The period just after WWII was a time that was both less fully pluralistic but also more outwardly religious than now. The opinions of Heschel and Niebuhr mattered more than they would today, when American liberal and moderate religious affiliation—as well as enrollment in mainline (that is, nonevangelical) Protestant seminaries and the more liberal (that is, non-Orthodox) Jewish seminaries—has been in decline. Last year the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, where Heschel taught for five years after being rescued from the Holocaust, announced closure of its rabbinical program begun in 1875 in favor of its East and West Coast branches.

The seminaries on Seminary Row and elsewhere exist, in important part, to build religious communities, and the sense of religious community in America has withered somewhat. A recent Gallup poll found fewer Americans—just 47%—now belong to a house of worship than at any time since Gallup began keeping track in 1937, a trend that this post-pandemic period has not improved. And among millennials, that demographic cohort born between 1981 and 1996, many now with young families, about 1 in 3 are religiously unaffiliated “Nones,” a high-water mark according to data from the General Social Survey.

Jews continue to be a small minority of about 2% of Americans. But non-Orthodox religious affiliation has been shrinking, powered by a lack of religious education, indifference, and privatized spirituality. The Pew Research Center’s 2020 study of the American Jewish community found that, while almost two-thirds of non-Orthodox respondents consider tikkun olam (“repairing the world,” or social justice) an essential part of being Jewish, barely one-quarter said the same thing about belonging to a Jewish community. And only 15% consider the observance of ritual commandments (Halacha) important, a principle still central to both Orthodoxy and the ethos of JTS. Even having a sense of humor, according to an earlier Pew survey, was considered a more important barometer of being Jewish than synagogue membership. (Niebuhr, incidentally, agreed that laughter, and especially self-deprecating humor, “has an important [religious] purpose” because all of us are “a little funny in our foibles, conceits and pretensions.”) By contrast, it is the Orthodox, approximately 10% of all American Jews but having lots of children, who are growing. Many also cultivate greater insularity because of a rightward religious shift among traditionalists in recent decades. Therefore, they have higher retention rates and a deeper sense of community.

At the same time, the larger self-identified American Christian population has declined a startling 15 percentage points to 63% in the past 15 years alone, according to Pew. Among mainline Protestants, the Episcopal Church, for example, has lost almost half its membership since the 1960s. It was in that decade that the so-called American Protestant establishment began to deteriorate, as it gave way to a more extensive palette of identities.

In a projection released last year, Pew concluded that if American Christians leave the faith at current rates (30% before age 30 and 7% afterward), by 2070 only 46% of Americans will be Christian, 41% will be Nones, and the rest will be Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, or something else. Protestants, who had constituted a large majority of Americans since the beginning of the republic, have now lost their majority status. Although evangelicals have also been losing members since their recent apogee in the 1990s, shrunken mainline denominations now total only about 16% of Americans, according to a report by the Public Religion Research Institute, significantly lower than even half a century ago.

But maybe, despite this oft-told tale of contraction, and precisely because they could connect with audiences across denominational and party lines, Niebuhr and Heschel will matter more again in this new time of foreboding, with the unprecedented horrors of Hamas and the continuing tragedy of Gaza, with the most extensive war in Europe since the Nazi era, with renewed antisemitism and other bigotries, and with angry debates that too often end in gridlock. A NORC/Wall Street Journal poll last year found over 80% of Americans believe the country is heavily split over the most important values, and that the situation will be even worse five years from now. Moral leaders like Heschel and Niebuhr who could bridge gaps have had a harder time being heard today because we have backed ourselves into contending little worlds of our own making, warring tribes that find it difficult even to converse without giving offense to one another. Meanwhile, according to a newly released NORC/AP poll, nearly half of all Americans have “hardly any confidence in organized religion.”

The friendship between Niebuhr and Heschel was most significant, historically, in the interreligious arena, where both theologians were pioneers of religious pluralism—against a backdrop of two institutions that were never a natural pair on Seminary Row. Niebuhr’s UTS was more theologically liberal than Heschel’s JTS, just as Niebuhr himself was more theologically liberal than Heschel. (Today there is a tighter weave between religious and political liberalism at both seminaries than there was just after WWII.)

Relations between the two seminaries have always been cordial despite their religious differences, though they have grown closer in more recent decades as the religious and social barriers between them have lessened. Mary Boys, the former UTS academic dean, a distinguished Catholic scholar of Christian-Jewish relations, and a nun teaching in a historically Protestant seminary, developed an interseminary teaching collaboration with JTS Chancellor Shuly Rubin Schwartz. Schwartz is a historian who has explored the roles of American rabbis’ wives and who in 2020 became only the eighth chancellor to oversee JTS in its now 137-year history. Today Schwartz and Boys cross Broadway with ease to visit each other’s seminaries, as Heschel and Niebuhr once did with what must have been, at times, greater muscular tension.

It was only in 1965 that Heschel became the first Jewish scholar to teach at UTS. The times were so different that, according to the UTS historian Robert Handy, even this liberal Protestant seminary had to change its constitution to allow a non-Christian to teach there. It was an exclusionary formality that is hard to imagine today in a highly pluralistic, post-Niebuhr UTS. Its website now touts the presence of two dozen faith traditions, including all the major world religions, to say nothing, for example, of Unitarians, many of whom no longer identify as Christian. Indeed, UTS now offers a concentration in “socially engaged Buddhism.”

But the implications of religious diversity and theological pluralism, with more expansive notions of religious truth, along with the diminution of a feeling of religious certainty that had existed for centuries, had not yet fully developed in the first half of the 20th century to become the major theological issue in all religions that it is today. In the same year Heschel crossed Broadway to become a visiting professor at UTS, Wilfred Cantwell Smith, the Protestant comparative religion scholar, could still write that the theological problem presented by religious pluralism, or whether religious “truth” inheres in more than one faith, “is really as big an issue, almost, as the question of how one accounts theologically for evil.” But he detected much less interest in the former issue, though the situation has changed dramatically in this century.

It was noteworthy that the formal installation last year of Schwartz as JTS chancellor, delayed by the pandemic, was covered not only by the Jewish press but also by The Christian Century, the most widely read mainline Protestant periodical, which as late as the 1940s had attacked Catholics. If one reads the Century regularly today, one finds that it is filled with a consistent and sympathetic amalgam of stories about other faiths, especially about Jews and Muslims.

Niebuhr and Heschel flourished in a postwar America where, particularly in response to “godless” communism and the misery of WWII, there was a turn toward religion. New churches and synagogues sprouted in the suburbs amid postwar prosperity, and membership rolls swelled. In 1958 President Dwight Eisenhower, an embodiment of the bland 1950s, laid the cornerstone at a massive new rectangular National Council of Churches building near Seminary Row, popularly known as the “God Box” or the “Protestant Kremlin.” It was an optimistic time, perhaps partially explaining the decision to relocate a Protestant headquarters to New York City where, unlike the Midwest or the South, Catholics and Jews each far outnumbered Protestants. (Today the building is home to many different faith groups.) Meanwhile, the Conservative movement in Judaism was adding as many as 100 new synagogues to its roster annually, with many members moving to the left from prewar Orthodoxy.

Feel-good self-help books by Protestant clerics like Norman Vincent Peale joined the bestseller lists. The Catholic Bishop Fulton Sheen brought religious broadcasting to a new high. The words “under God” were added to the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954. Was it a genuine religious revival or mostly a desire for a settled sense of community? Whatever the answer, Eisenhower suggested that just being religious was what counted, more so than the specific religious box one checked. Catholics and Jews now took on a more prominent role in a tri-faith America, albeit one that still did not take seriously enough the particularities of the Black, Hispanic, and Asian churches and the faiths that then still had a much smaller American footprint.

Meanwhile, the centrist Conservative movement is now likely to become the smallest of the three major American Jewish “denominations,” with, according to Pew, less than 10% of young American Jews explicitly identifying with it. But in the immediate postwar era it grew to become the largest. UTS was already the largest Protestant seminary in the north when Niebuhr joined, but in the 1960s its enrollment climbed to almost 800, the highest in its nearly two-century history, compared to about 200 today.

On a popular level, extensive American prejudice against Catholics and Jews had only recently receded in the 1950s. Catholic upward mobility, increased wealth and influence, and a corresponding assertiveness rankled the Protestant majority. Similar resentments festered toward Jews where, in 14 separate opinion polls from 1938 to 1946, an average of almost half of Americans said American “Jews have too much power,” evidently including too much wealth and cultural influence, too. The Holocaust gradually changed that, though the resurgent antisemitism seen recently may change it again.

American prejudice against Muslims would arise later. But Muslims were still rare enough in the 1950s that Niebuhr could refer to them as “Mahometans,” an offensive term today because it centers the faith in a human being rather than in God as the term Islam (submission) does. Heschel never even met a Muslim until shortly before he died. He said: “[W]hile I have prayed from the heart for the Muslims all my life …, I have never been face-to-face with them to talk about God.” Last year marked the rare convergence of Ramadan, Easter, and Passover. On the night that a public television documentary on Heschel’s life by the Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Martin Doblmeier had its in-person premiere in the JTS auditorium, the seminary was hosting a Ramadan iftar (break-fast) dinner in support of its Muslim neighbors. (UTS also excels in hospitality of this sort.)

Mormons, who are 16 million-strong today, comprised only about 1 million adherents just after WWII, mostly in Utah. Few had even met a Hindu or a Sikh or a Buddhist, though today there are more Sikhs in the world than either Mormons or Jews. And there was more consensus between the right and the left. In 1952 only half of Americans saw a big difference between Republicans and Democrats; by 2020, 90% did. There was, to be sure, a stifling social uniformity that disfavored women, gays, and minorities, but there was also greater trust than now in American institutions and in religious leaders like Niebuhr, Heschel, and, larger than any of them, Billy Graham.

On a theological level, while 9 in 10 Americans today believe that good people of any religion will get into heaven, prior to the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church held—as it had throughout most of its history and in line with many evangelical theologians even today—that Christianity provides the exclusive means of personal salvation. Christianity was seen to have superseded Judaism, hence the theological term supersessionism, rendering the latter spiritually defunct and necessitating conversion to Christianity, the repository of supreme religious truth.

In part to ameliorate the effect of these views, the two seminaries stepped up efforts to meet across Broadway. The two-volume official history of JTS devotes a whole chapter to intergroup relations advanced by Louis Finkelstein, its chancellor from the 1940s through the 1960s. Though little is said specifically about relations with UTS, John Coleman Bennett was a UTS president of the time who made reciprocal efforts. But Niebuhr’s influence was also decisive.

In 1957 Niebuhr delivered a bold lecture to the first-ever formal joint gathering of the JTS and UTS faculties. There he argued that, contrary to centuries of firm precedent and his own pro-missionizing sentiments as a young man, it was wrong to try to systematically convert Jews to Christianity because the two religions, despite important differences, are sufficiently similar in line with the common Judeo-Christian heritage that Niebuhr did much to promote. This speech would eventually strike a blow for even more inclusive notions of religious pluralism.

Niebuhr, who was 15 years older, had given Heschel his first significant national exposure. In 1951, a year before he suffered a debilitating stroke, Niebuhr wrote a highly positive review of one of Heschel’s earliest books in English, Man Is Not Alone, calling the then 44-year-old Heschel “the most authentic prophet of religious life in our culture.” It was after Niebuhr’s milestone twin faculties lecture on religious pluralism that the bond between him and Heschel apparently deepened. Heschel returned the favor eight years later when he became the first Jewish scholar to be appointed a visiting professor at UTS. And his now famous inaugural lecture at UTS, “No Religion Is an Island,” extended the boundaries of religious pluralism even among some, like Heschel himself, who also had traditionalist leanings.

Living up to the only half-serious designation of Heschel as an apostle to the gentiles, Heschel, too, stressed similarities between religions, arguing that “religious isolationism is a myth,” that “sooner or later [each of the religions is] affected by the intellectual, moral and spiritual events” of the other, and that Christianity and Judaism needed each other as a joint moral force in the world. Although Heschel conceded that, in their conflicting claims of propositional religious truth, “Jews and Christians are strangers and stand in disagreement with each other,” nevertheless, he argued, religious “[p]arochialism has become untenable” because in a globalized world it becomes harder to stand apart and claim one’s own faith has a “monopoly of the holy spirit. … The voice of God reaches the spirit of [humans] in a variety of ways, in a multiplicity of languages. One truth comes to expression in many ways of understanding … In this aeon diversity of religions is the will of God.”

Heschel was wrong about the staying power of religious parochialism in the world, but he would go on to become a primary Jewish interlocutor in the revolutionary Catholic Church reforms of the 1960s that comprised the Second Vatican Council. His Catholic counterpart was a saintly German cardinal, Augustin Bea. It did not always go smoothly. For example, Heschel publicly exaggerated his discussions with and influence on Pope Paul VI. But in the end no harm came of any of it, and Vatican II transformed the Catholic Church and with it Jewish-Christian relations. Vatican II renounced the notion that Christianity had superseded Judaism and rendered it defunct. It also repudiated charges of deicide, condemned antisemitism, and omitted mention of any hope for wholesale Jewish conversion. It also cultivated a fresh appreciation of the Hebrew Bible and the Jewishness of Jesus.

Vatican II was only the beginning according to Mary Boys, who recalls being a pre-Vatican II teenager in Seattle, not permitted by Catholic teaching to attend the bar and bat mitzvah services of her friends. Since Nostra Aetate (In Our Time) in 1965, Vatican II’s proclamation on interfaith relations, multiple pronouncements from both the Catholic Church, and many Protestant bodies following in its wake, have begun to view Judaism as well as Islam and other religions as living faiths, entitled to their own dignity rather than serving as examples of religious error and foils for a sometimes-triumphalist Christianity. These new efforts of enhanced respect are also slightly more than a half-century old.

Nostra Aetate also recalls the 20th anniversary last year of a corresponding proclamation signed by an unofficial group of over 200 Jewish leaders titled Dabru Emet (Speak Truth). It saluted these major theological changes in a show of reciprocal respect. Then, more than a decade ago, Boys’ own friendship deepened with JTS Chancellor Schwartz on the other side of Broadway, and they joined forces to teach the largely upsetting history of pre-Vatican II Christian-Jewish relations to a mixed group of JTS and UTS students. According to Boys, this course would have been a nonstarter barely 50 years ago when Niebuhr and Heschel were still alive.

A coming to terms with the realities and theological implications of American religious diversity that Heschel and Niebuhr did their part to further more than 50 years ago is mirrored in a different sort of diversity today on Seminary Row. There, a majority of the ministers and rabbis ordained at UTS and JTS are now women, and many identify as LGBTQ. Even the Talmud and Rabbinics Department, for centuries an exclusively male bastion, is today headed by Marjorie Lehman at JTS. And while the Catholic Church still does not ordain women, an important Vatican synod is currently discussing the ordination of women as deacons and blessings for same-sex couples—to the dismay of traditionalists who warn of compromising “basic truths” of Catholic doctrine.

In addition, people of color are far more visible at UTS than in Niebuhr’s time—in line with the seismic shift of Christianity to the global south and the burgeoning number of Latino Protestants on a formerly monolithic Roman Catholic continent. (According to Pew, only 36% of U.S.-born Latinos now identify as Catholic.) Soon the largest share of the world’s Protestants will have roots in Africa and Latin America, not Europe and North America. Moreover, the world Jewish population is no longer divided simply between Ashkenazim (lighter-skinned Jews from Germanic lands) and Sephardim or Mizrahim (darker-skinned Jews from Mediterranean areas).

The 2020 Pew Research Center study of the changing American Jewish community found that, due primarily to increased intermarriage, adoptions, individual conversions, and even rediscovery of heritage based on DNA testing, only 49% of Jewish young adults ages 18-29 now have two parents who are Jewish by birth, and 15% identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian, or other. Cornelia Dalton, a recently ordained JTS rabbi, is one example of UTS and JTS seminarians who grew up in homes with a mixed religious heritage. She has a stop-them-in-their-tracks comeback when someone tells her she’s half-Jewish because of her Catholic father. “Is that my top half,” she asks, “or my bottom half?”

More diversity is coming in American Judaism because it is more open to outsiders as a religious option than it has been for centuries—a far cry from the Christianized Roman Empire, for example, when helping someone who wanted to become Jewish was a capital crime. According to Rick Jacobs, who leads the liberal Reform movement, now the largest in American Judaism, assisting outsiders to feel welcome in Jewish communities has now become a matter of “theology” rather than mere sociology.

Meanwhile, until not long ago virtually all Christian and Jewish theologians have been male, and female theologians have been rightly critical of them. But both Niebuhr and Heschel still might be pleased that, for the first time, both seminaries are now headed by women (Schwartz at JTS and Serene Jones at UTS) because last year also marked a half century since the first woman rabbi (and 45 years since the first female Episcopal priest) was ordained in the United States. It was also the 100th anniversary of the first American bat mitzvah, which involved the daughter of a leading JTS scholar, Mordecai Kaplan, and also took place on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, not far from Seminary Row.

For more than two decades Gordon Mehler, a lawyer, has lived near the neighboring seminaries where Heschel and Niebuhr taught. His articles have appeared in The Atlantic, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal.