Struggling with the feeling of helplessness that has gripped so many in the aftermath of Hamas’ Oct. 7 atrocity and Israel’s ferocious response—exhausted, depressed and depleted from the endless scroll of war coverage, the instant polarization, and the flood of reactive hot takes followed by reactions to those—I found myself at home one November evening reading The Merchant of Venice. I couldn’t exactly say why. I did it on impulse, probably springing from the same source that has led others I know to sign statements, attend various marches, buy guns, or post video reels on Instagram. Reading is one thing I’ve always done to feel both connected and safe.

Like everyone else in the chattering class to which I belong, I suppose I too was feeling a vague but increasingly intolerable pressure to “say something.” Already friends had stopped speaking to me because I refused to endorse their renewed calls for an “academic and cultural boycott of Israel” in the wake of Oct. 7 (well before Israel had even begun its military response). I resigned from my ceremonial masthead position at the magazine I’d founded 20 years ago because I’d questioned the editorial wisdom of publishing an unapologetic, celebratory account of the pro-Palestinian rallies on Oct. 8. I was told that this was how the people now running things wanted it.

My public persona is that of a literary critic. I’m no expert in the politics, history, or great power realpolitik of the region Americans call the Middle East. Yet, I was constantly being challenged by people who almost certainly had read and knew less than I did to make a statement or sign a statement, to participate in the contemporary ethics and aesthetics of position-taking that constitutes “public intellectual life” in the era of Substack and X. My editor at Tablet—without any animus—told me my decision to write my November column about a quirky, punk historical novel by an assimilated British Jew was like someone who responds to horrifying news by “taking a warm bath and listening to the Pixies.” So, fine, I would pour lavender bath salts on my wounded ego and read The Merchant of Venice. Maybe I’d have something to say about it.

It had been a while since I’d last looked into Shakespeare’s Jewish play, possibly when I was in graduate school, or maybe more recently, after a 2017 conversation with the Kashmiri writer Basharat Peer. Basharat, a friend, is the author of an astounding film adaptation of Hamlet (Haider, 2014). He’d mentioned that he was thinking of tackling The Merchant of Venice, setting it in Mumbai with Shylock as a member of that city’s historically persecuted Shi’ite Muslim minority. The truth is that the play had never much resonated with me in previous readings and the two performances I’d attended. That was the case this time, too.

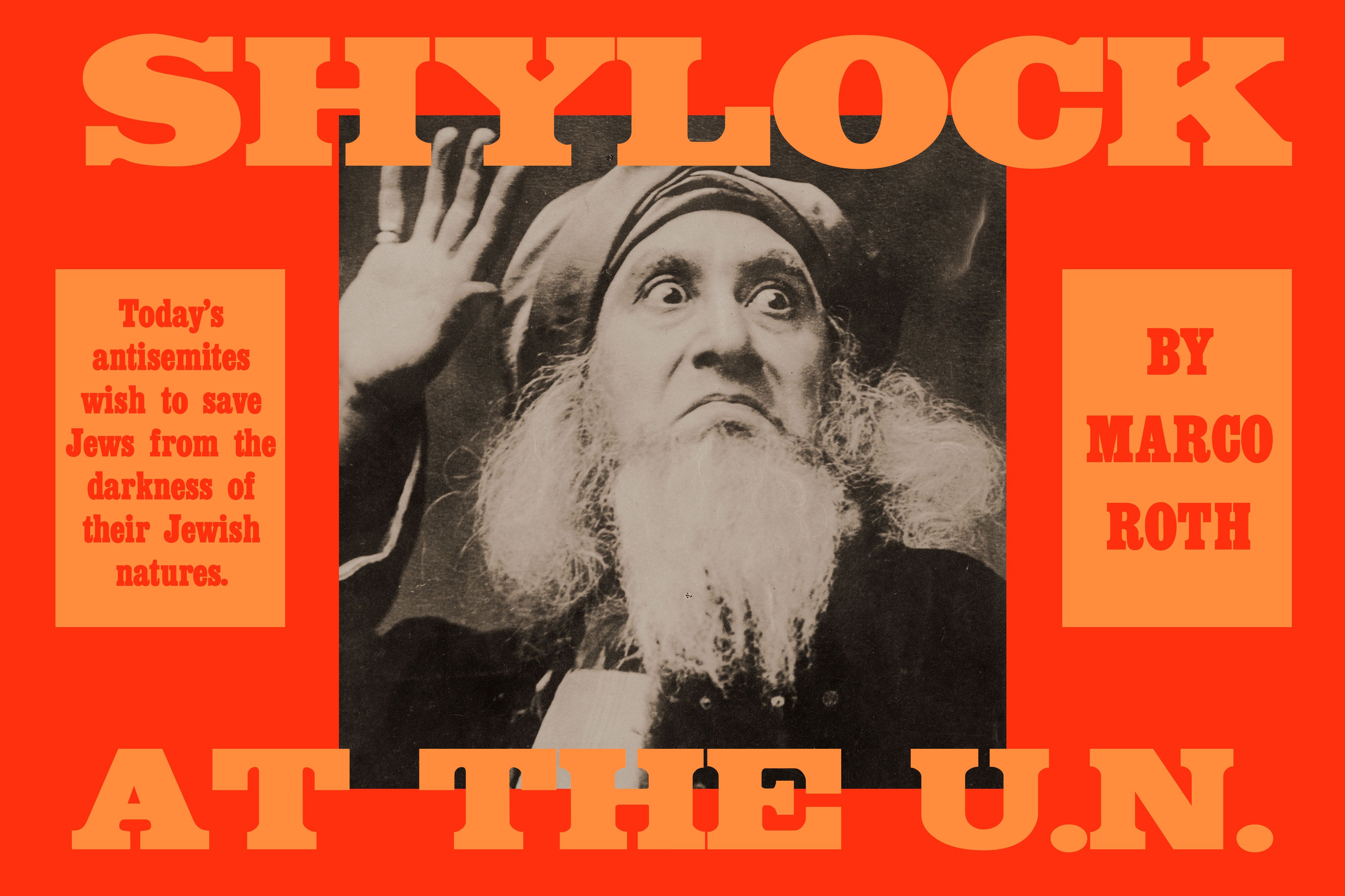

For one thing, The Merchant of Venice is clearly a drama for and about gentiles. The Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro once devoted an entire book, Shakespeare and the Jews, to arguing that “the English turned to Jewish questions in order to answer English ones.” Shylock is not a play for Jews, but rather a play that reveals the large role that the figure of the Jew played in the minds of early modern (late 16th century) English people. Jews were a mirror of misprised identity, both identified with and identified against.

The titular merchant is not Shylock, a moneylender, but Bassanio, a profligate chancer who draws on the credit of his friend and would-be lover Antonio, prevailing on him to borrow 3,000 ducats against the infamous pound of his own flesh to finance a long shot marriage-for-money scheme. The play was considered a comedy—which is to say that all’s well that ends well for the characters meant to garner the audience’s sympathies. It’s possible that Shakespeare deemed Shylock’s ultimate humiliation a happy ending for the Jew as well, since there were worse outcomes for a Shylock in the Elizabethan world and its cosmology than being stripped of all his worldly goods and being forced to convert to Christianity on pain of death. He might have been hung, drawn, and quartered as an alleged “poisoner,” like Queen Elizabeth’s personal doctor, the converso Rodrigo Lopes, in 1594, one of a few people of Jewish descent allowed legal residence in England at the time.

The plot and pacing of the play assumes an audience that will take pleasure in the frustration of Shylock’s revenge scheme and in his subsequent humiliation. This remains true despite the Shakespearean genius for character that allows us to glimpse the proud, stubborn, raw, aggrieved and stunted human being beneath the Jew’s gabardine.

I read ‘The Merchant of Venice’ on impulse, probably springing from the same source that has led others I know to sign statements, attend various marches, buy guns, or post video reels on Instagram. Reading is one thing I’ve always done to feel both connected and safe.

Malignancy, in Shakespeare, with the avowed exception of Iago, always has a motive; even a random hit man in Macbeth gets to state his case: “I am one, my lord, who the wretched blows and buffets of the world have made me reckless at what I do to spite the world.” So Shylock comes on stage brimming with motivated grievances, chafing against the indignities and “the suff’rance” that is “the badge of all our tribe.” “You that did void your rheum upon my beard, / and foot me as you spurn a stranger cur / over your threshold moneys is your suit. What should I say to you? ... ‘You spurned me such a day, another time / You called me dog: and for these courtesies / I’ll lend you thus much moneys’?”

Whatever the merits and measure of Shylock’s anger, the play also continuously invites us to find him repulsive, to jeer from his first line (“Three thousand ducats, well.”). We are to despise him—for this is what it means to be a Jew: to be despised, not for anything in particular but precisely for nothing in particular, only because a Jew. To attend to The Merchant of Venice means you inhabit a worldview hostile to Jews by default. It’s not an “antisemitic” text, it just belongs to a world of routine, consensus Jew-hating and Jew-baiting. The same world asks us to partake in Bassanio’s admiration for the object of his affections, the woman he stakes his friend’s life to win, the “fair (and fairer than that word)" Portia—she of the three caskets, a fine legalistic turn of mind, and a great portion of inheritance.

And here too I felt frustrated. Portia’s famous exhortation to Shylock to be merciful, in which she expounds the essence of Christian charity and justice that transcends both reasons of state and reasons of law, “The quality of mercy is not strained ...,” has always struck me precisely as strained, or as straining for effect. Perhaps this is because I first heard the lines pronounced during a high school Shakespeare competition by an actress who struggled to understand the meanings of all the words. Or perhaps also because in what follows, once she has turned the tables and has Shylock in the dock, Portia, disguised as the young legal scholar Balthasar, shows herself to be something less than merciful.

Having rescued Antonio with a literal reading of the pound of flesh contract that would make any Talmudist proud, she then turns the tables with two ominous words that render Shylock both more and less than a single nasty man who has lost a court case: “Tarry, Jew.” Harold Bloom refers to Portia as a “delightful hypocrite,” which neatly sums up her contradictions.

Present events have revealed many such Portias, with the example of Francesca Albanese, the United Nations special rapporteur on the occupied Palestinian territories only one of the most flagrant. Albanese has not only argued that Palestinians have a “right to resist” by any means, however unnecessary, but also that Israel as an occupying power on disputed territory (which, by her account, could include the 1948 boundaries of Israel as previously determined by the body she represents) does not possess a right to self-defense.

But that’s getting ahead of my argument. It makes little sense to quarrel with a work of literature written nearly 420 years ago, or try to find points of sympathy, or, worse, identification with its characters. Not only was the play not written for Jews, it wasn’t written for moderns either. It wasn’t until 1814 that an actor (the great Edmund Kean) first ventured to play Shylock for sympathy and gave a modern and moving turn to the lines that any Jewish lover of Shakespeare probably knows by heart:

Hath not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer as a Christian is?—If you prick us do we not bleed? If you tickle us do we not laugh? If you poison us do we not die? And if you wrong us shall we not revenge?

This can sound like humanism or at least a case for equal rights. But, after watching Kean as Shylock, the critic William Hazlitt understood the undertone of menace behind the plea for recognition: “Our sympathies are much oftener with [Shylock] than with his enemies. He is honest in his vices; they are hypocrites in their virtues.”

The culmination of this contrast between villainous honesty and virtuous hypocrisy comes at the outset of Shylock’s trial, when Shylock puts his case to the Duke of Venice in terms he might understand, “You have among you many a purchas’d slave, Which (like your asses, and your dogs and mules) you use in abject and in slavish parts, / because you bought them. Shall I say to you, / Let them be free, marry them to your heirs? ... You will answer ‘The slaves are ours’—so do I answer you: The pound of flesh which I demand of him / is dearly bought, tis mine and I will have it.” Shylock is only asking for the same rights of any “bond holder” in a slave-owning society. But what kind of justice is that?

One can imagine how Hazlitt and Kean, both abolitionists, would have received those lines in 1814. But they were both of the same era and sensiblity—sometimes called “Romanticism”— that thought Satan the hero of Milton’s Paradise Lost and shared William Blake’s observation that the poet was “of the devil’s party without knowing it.”

Present events have revealed many such Portias.

This ability to give voice to the “reasons” of passions in all their fervor, is what makes Shakespeare modern, or “ahead of his time,” or “the inventor of the human,” as Harold Bloom argued, with Shylock, Hamlet, and Falstaff as crucial examples. But it is more likely that contemporary audiences heard these pleadings as a special kind of rhetoric: variations of a “devil’s argument.” The play baits the audience with the possibility of sympathizing with Shylock, much in the way—according to Stanley Fish in Surprised by Sin—Milton baited his audience into sympathizing with Satan. Like Satan, Shylock may get some of the best lines, but “in context,” as certain former university presidents might say. For the Jew in a world ultimately ruled by a gentile god and gentile justice, there’s neither equality of condition nor chance of redemption.

A “fair” or outwardly persuasive rhetoric or appearance that conceals a shady, malevolent, or foul intention and essence unites the play’s marriage plot with the secondary Shylock plot or counterplot. Bassanio, when he has to choose among the caskets, foreshadows Shylock’s later trial, “So may the outward shows be least themselves, / —The world is still deceived with ornament— / In law, what plea so tainted and corrupt, / but being seasoned with gracious voice / obscures the show of evil.” So at least suggests the long dead J.R. Brown in his rather genteel (gentile?) midcentury introduction (1955) that still lives in zombie reprint in the 2005 Arden edition I had closest to hand. (Arden intro: Lii). The Jew can both look and talk like any other person, but inside he lacks grace. The Jew is “unfair,” so it is not (to the Elizabethan mind, at least) unfair to discriminate against the Jew.

Taking this interpretation to its logical conclusion would mean that the play pushes its audience to judge not by appearances or performance but by the invisible interior or content of the character. On stage, however, the results of these nuanced distinctions often align with and reaffirm instinctive and superficial prejudice.

One of Portia’s suitors, the King of Morocco, reveals himself to be a narcissistic man-child, boasting about his martial and sexual conquests and choosing the casket that promises only “What many men desire.” But Portia was already turned off at first sight on account of his skin color, and hails him offstage with the aside “Let all of his complexion choose so.” Some of the audience at the first recorded court performance of The Merchant of Venice, in 1605, might also have attended the first production of Othello the previous year, and would endorse the prejudice, knowing how a Moor is likely to strangle his wife over a misplaced handkerchief. Likewise, Shakespeare’s audience, some of the same people who openly laughed at Rodrigo Lopes’ profession of loyalty to the Queen as he was being disemboweled, probably knew not to trust Shylock’s fine words, nor his insistence on the letter—that is the face—of his agreement with Antonio.

Distinctions between comic and tragic in Shakespeare’s time were not about funny versus sad as much as outcomes. Comedy is the name applied to those dramas that end with the restoration or reaffirmation of a perceived natural order of the universe in the best of all possible worlds: The lost are found, the true king crowned, the lovers meet their right partners in accord with their looks, habits, and, most importantly, status.

That comedies have their victims and their losers too was an insight of a later age that derived from Shakespeare. Bloom refers to that trio of “comic villains: Shylock, Malvolio, and Caliban” who each seek to rise above their status: Malvolio the steward, Caliban the slave, Shylock the Jew. Each of these characters introduces elements of tragedy into the comic universe through the cruelties visited upon them. The comedy of The Merchant of Venice is Shylock’s tragedy.

All of this is to say that whether in 1598, 1605, 1814, or 2023, The Merchant of Venice offers up a theater of justice in the case of a Jew who is both wronged and vengeance-seeking. This Jew operates in a hypocritical gentile world governed by gentile laws both written and unwritten, according to which the audience judges the Jew’s case according to their own prejudices. In this way The Merchant of Venice continues to provide a paradigm for certain ideas of justice and fairness, both for Jews and about Jews in the so-called courts of “international law” and Westernized “public opinion.”

This brings us to what I’d like to call, in reaction to the current iteration of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, “Shylockism.” Let me be clear that in writing about the Oct. 7 Hamas attack and the ongoing Israeli invasion of Gaza precisely as “a spectacle,” I am in no way diminishing or dismissing those real lives destroyed by Hamas, Hezbollah, and the IDF, physically and psychologically. I am dealing only with how a multitude indirectly affected by the ongoing war are processing the conflict in its spectacular or rhetorical dimensions, on the great world stage of the internet, a place where we, as both actors and audience members, are always being asked to infer essences from appearances and render judgment based on an apparent surplus (Shakespeare would say “surfeit”) of information and details that are overwhelming and yet always insufficient.

Upon this stage, where we can see and hear so much—too much—suffering and tracking it in almost lived time, we inevitably come to organize the plentitude of information we receive according to received narratives about Jews and how Jews deal with others. Shylockism is one name for one of these stories.

I would suggest that a lot of what Jews have recently perceived as antisemitism—at least from institutions and otherwise mild-mannered advocates of boycott and sanctions and shunning—would be better understood more specifically as Shylockism, a subtype of antisemitism that often does not feel like “Jew-hating” to those engaged in it. Shylockism often comes across as a wish to save Jews from themselves, most especially from Jewish anger, however righteous, by making them into something else, either through assimilation / conversion (as with Shylock’s daughter, Jessica) or through an extra-legal but pseudo-legal framework—adherence to a higher law—that will ensure a happy end for everyone, once the Jews have renounced their claims.

Shylockism also effectively names the persistence of a certain kind of “imaginary Jew” that lives in the heads of gentiles—and now, thanks to modernity and Jewish assimilation, governs the imaginations of many Jews as well. In its contemporary form, the Shylock story comprises two tendencies at once:

1. the tendency among gentiles to urge wronged and angry Jews to show exceptional mercy on those who have wronged them ... or else.

2. the countertendency among certain Jews to argue in the courts of Western public opinion that their own suffering and victimization gives them no choice but to be “as bad as the gentiles.”

The first of these cases is fairly obvious. In the aftermath of the Oct. 7 attacks, there were a number of highly publicized instances of mercy-splaining to Israelis but that were really playing to the gallery of international public opinion. Francesca Albanese, the would-be Portia, is the most egregious example, but as someone who has openly and wholeheartedly espoused the Palestinian cause at the expense of Israelis and Jews, she’s less interesting than other more unconscious instances of the phenomenon. Josep Borrell, the European Union’s head of foreign policy, used a visit to Kibbutz Be’eri to ask Israelis, “not to be consumed by rage.” U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres spoke about understanding the attacks “in context” during an Oct. 24 address devoted to urging both sides to respect international law. Each of these phrases was cited and reported “out of context” by official Israeli spokespersons and the press as signs of an anti-Israel bias. Yet both Borrell and Guterres (Catalan and Portuguese Catholics respectively) seemed genuinely baffled to be so accused.

Neither of the two European diplomats could see how asking the Jewish state to show exceptional restraint, neither to succumb to a perceived emotional atavism (the Old Testament law of reprisal), nor to ignore a suite of alleged historical injustices carried out against their adversaries, might be seen as casting Jews back into roles from a European Christian passion play, rather than addressing Israelis as a modern nation dealing with the aftermath of a horrific cross-border attack on its civilians by a terror army. Borrell is basically saying “don’t be so Old Testament” and Guterres, “well the Jews must have done something to deserve this.”

It seems obvious that neither diplomat would ever have thought of urging restraint upon Islamic nationalists, or an understanding of a broader context to Palestinians, who are implicitly granted a freedom of action that comes from being outside of a Judeo-Christian cultural imaginary (though often enrolled in a different one—I’m looking at you Caliban). Indeed, one searches in vain for similar calls by European and U.N. leaders for anger management to Assad in Syria or Erdogan in Turkey. But, in the case of Israel, a Jewish demand for justice (or retribution) in the here and now is an inevitable, and perhaps even pleasurable, occasion for hardened diplomats to open up the possibility of an ultimate or final justice that will transcend justice, in the process of which the Jew will be inducted into the ways of mercy.

A similar dynamic can be seen at play in President Biden’s account of a recent conversation with Prime Minister Netanyahu:

It was pointed out to me—I’m being very blunt with you all—it was pointed out to me , by Bibi, that ‘Well, you carpet-bombed Germany. You dropped the atom bomb. A lot of civilians died,’ I said, ‘Yeah, that’s why all these institutions were set up after World War Two to see to it that it didn’t happen again—it didn’t happen again. Don’t make the same mistakes we made at 9/11. There was no reason why we had to be in a war in Afghanistan at 9/11. There was no reason why we had to do some of the things we did.

In Biden’s gaff-prone way, he admits that these institutions of international law set up after World War II and intended to prevent massive civilian casualties were ignored again and again by the United States, most recently during the Afghanistan war, thereby contradicting his statement that “it didn’t happen again.” He’s also implicitly urging Netanyahu to set a better example than the United States has. The quality of mercy is not strained and becomes the throned monarch better than his crown.

A lot of what Jews have recently perceived as antisemitism is better understood as Shylockism, a subtype of antisemitism that often does not feel like ‘Jew-hating’ to those engaged in it. Instead, it often comes across as a wish to save Jews from themselves.

In the way that, according to James Shapiro, The Merchant is not about Jews but rather a projection onto Jews of another people’s anxieties, so is the ongoing drama of Israel-Palestine. Biden turns a dialogue about Israeli national security and how that country should respond to terrorism—not being a global terrorism expert, I personally don’t know!—into a stream-of-consciousness soliloquy full of belated and uneasy American guilt and doubt about its own response to terrorism and insurgency, in parts of the world that are certainly much farther away from U.S. borders than Gaza is from Israel’s.

The Biden-Netanyahu conversation also shows the first tendency of Shylockism running headlong into the second. That is, Jews claiming the right to be as bad as gentiles, because they can imagine no other recourse. We don’t know if Bibi said exactly what Biden said he did: Biden may have been hearing Israel’s leader through the same distorting field that is audible in the rest of his account. Yet much of the historical rhetoric of Zionism as well as the State of Israel’s own messaging amounts to a kind of “honesty in vice” that attempts to justify actions seen as excessive through appeals to a tarnished self-image of “Western civilization” from which Jews were historically excluded and “Western nations” no longer want to defend.

What remains exceptional about Jews and the Jewish state is a wish to exit a state in which Jews must be exceptional, either exceptionally good or exceptionally bad. But this desire to be like others is also an old wish that runs through the heart of modern Jewish experience, going at least as far back to the time of Shylock and Rodrigo Lopes, and is inextricable from the searing prejudices that provoked it, at times becoming their obverse.

In a remarkable interpretation of The Merchant of Venice that turns on the question of what it meant to be a human being and a man in 16th-century Europe, the critic Marc Shell suggests that much of Shylock’s behavior is “out of character for a Jew.” Specifically, Shell notes Shylock’s contract with Antonio as being inherently goyish. As he writes, “The apparent commensurability between persons and purses which this enactment reveals turns out to be more typical of Christian law, which allows human beings to be purchased for money, than Jewish ‘justice’ and practice, which disallow it.”

Shylock is not afraid to say or do in broad daylight—transact with human flesh—what the Venetian nobles are themselves ashamed of. Shylock’s mention of slavery is the first time slaves appear in the play, although one might wonder what cargo Antonio is indeed trading to and from Mexico and the Indies. The play’s response to this is to invoke something beyond the law: Portia’s merciless mercy dressed up in judicial robes. It is through the invocation of mercy that Shylock inherently lacks that the crimes of the nobles of Venice are made to disappear from view. Without Jewish guilt, there can be no Christian innocence. I don’t like it.