The death of a soldier dissolves some of the informality of Israeli life. Gal Eisenkot, the 25-year-old son of Gadi Eisenkot, a former Israel Defense Forces chief of staff and an observer in the war cabinet, died on a Thursday afternoon. He had to be buried on Friday morning, as soon as possible and before the early start of a winter Shabbat. There had to be infrastructure in place for family, friends, the wartime leadership of the country, and multitudes who had never known Eisenkot in life. A tent-shaded gravesite with rows of chairs and bags of earth had materialized according to a strict halachic timeline in the old cemetery in Herzliya, where cigarette-smoking policemen with the seal of the State of Israel on their black yarmulkes stalked through a network of metal crowd barriers.

At the cemetery gates, volunteers representing no organization—Israelis who had acted on an impulse to help—handed out packets of tissues as thousands of mourners filed into the spaces between the graves surrounding the tent, which rose from the cemetery’s military section.

An announcement rang out: In the event of a red alert, God forbid, we were to stand in place with our hands on top of our heads for protection. Aren’t we supposed to lie down during a rocket attack? I mused to a nearby mourner, an American-born man with a wild gray beard, wearing an IDF uniform from a distant era. Where would you lie down? he replied, pointing to the grave in front of us, resting place of Moshe Halpern, a veteran of the pre-statehood Haganah. With him?

Gal Eisenkot had been alive less than 24 hours earlier, when an urban land mine planted under the asphalt—a “tunnel bomb”—detonated during an operation to rescue two hostages in Jabaliya, in the northern Gaza Strip. These hostages did not leave Gaza alive. A photograph the IDF released later that week showed their flag-draped bodies departing a ruined street in the middle of the night on the back of a mud-green Humvee, in the company of fully kitted special forces whose faces were blurred out.

The beginning of the funeral commanded an awesome silence from a vast crowd, a national cross section made of sturdy aging men wearing caps with the insignia of a dozen IDF units and middle-aged parents with their teenage children, dressed in jeans and cargo shorts and black sunglasses. Between the bird cries and the whoosh of circling helicopters, under the glare of an unseasonably hot morning, the father, sister, and close friends of the dead man gasped to steady themselves as they struggled through brief and disbelieving eulogies, every voice a pain-stricken battle against the unimaginable fact of even being there.

The only exception was the heroically steady Benny Gantz, the former IDF chief of staff. “When we approved plans we knew their meaning,” Gantz said in his remarks. “We knew that the arrows on the maps could become arrows to the heart of good and dear families.” Sending the children of your friends and colleagues to their deaths was part of the holy and awful work of Israel’s survival: “Blessed is the land whose sons are like Gal.” After Gantz spoke, a bone-thin old man in a loose-fitting olive uniform put on an orange pair of gardening gloves and untied the bags of earth.

Within the anguished graveside blur of family and battle comrades and cabinet ministers, Benjamin Netanyahu became distinguishable only when he was called to lay a black memorial wreath. He looked ashen, defeated, long lines streaking his face, mouth in a half-scowl, eyes retreating into his head. The prime minister and a small security detail rapidly snaked its way to the back of the tent.

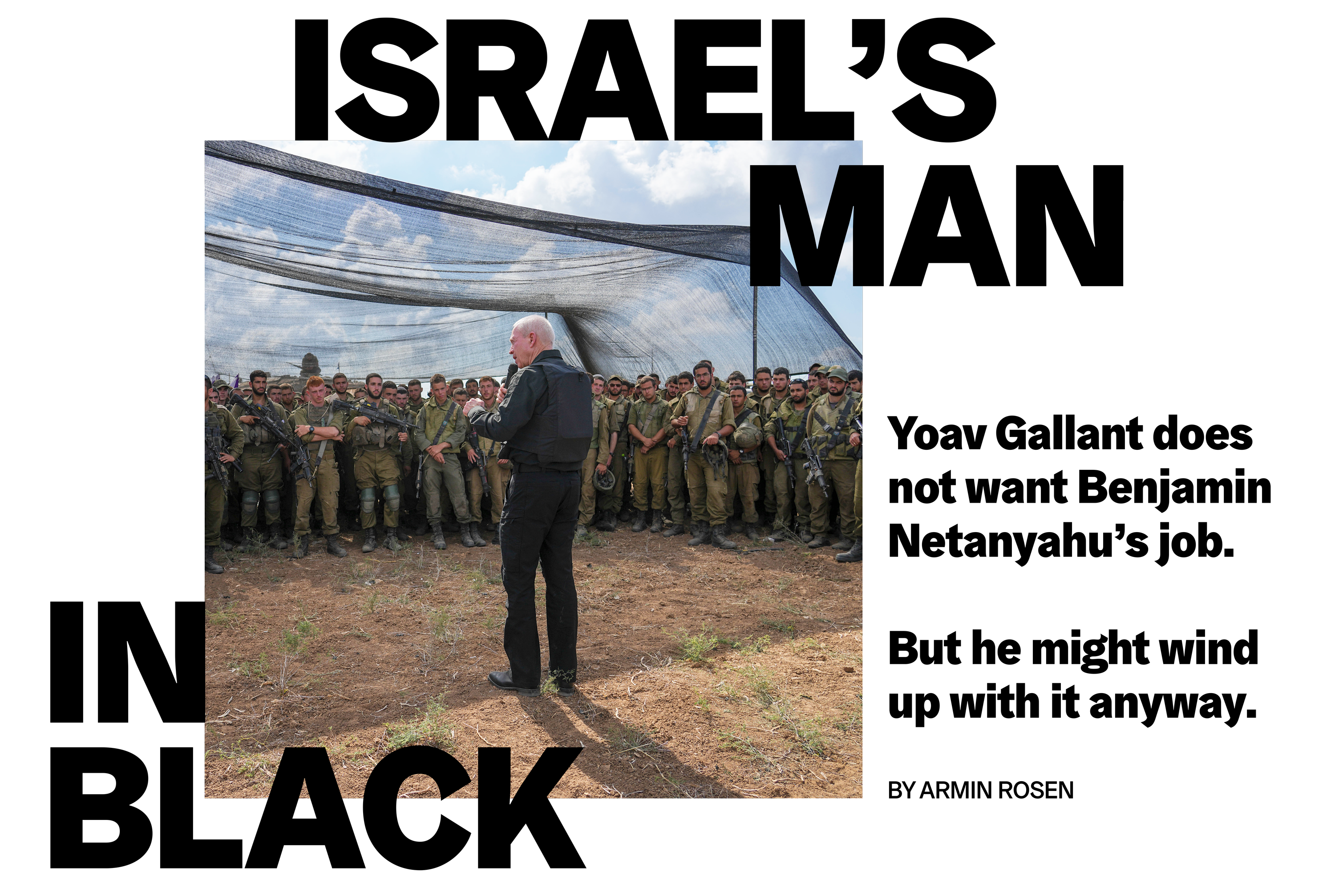

Towering amid the graveside crowd was Yoav Gallant, the defense minister. Since Oct. 7, the only outfit Gallant has worn is a Uniqlo-style double-breasted black shirt with black buttons, open enough at the top to reveal a black undershirt, as well as black pants held up with a military nylon black belt and black dress shoes as featureless as wooden clogs. The voidlike uniform communicates mournfulness, gravity, and perhaps a note of penance from the retired general and 30-year IDF veteran, who was Israel’s top civilian security official on the deadliest day in its history. That he continues wearing black means the goals of the war haven’t been achieved yet, which means there are still a quarter-million internally displaced, 350,000 soldiers mobilized, and 130 people in Hamas captivity. It means there are still Israelis dying in Gaza nearly every day.

When it was his turn to lay a wreath, Gallant, whose wife is a retired lieutenant colonel and whose children have served in special forces units, knelt at the grave, rose, spent an endless second staring down at the blank vessel that encased the son of a close colleague who had died on their watch, and then executed a sharp 90-degree military turn before merging back into the crowd.

Eisenkot, Gantz, Gallant and Netanyahu have been at the highest levels of their country’s leadership for much of the past 15 years. The funeral in Herzliya was only the latest and starkest confrontation with the reality they’d made. The sons of Israel’s founding generation had squandered a national patrimony that it might be too late to recover—a feeling and a reality of optimism, an ability to see the world clearly and to meet its challenges no matter what that required, ownership of a national destiny that Jews had no choice but to control themselves. Now they can only regain it all through months or even years of violence, and at the expense of their own children’s lives.

But these days, the war cabinet barely functions. Most everyone believes that the only three people who really matter are Netanyahu and Gallant, both of the Likud Party, and Gantz, who joined an emergency unity government the week after the Oct. 7 massacre (the final two members, observers Eisenkot and Ron Dermer, are backers of Gantz and Netanyahu, respectively). These people do not work well together and don’t seem to like each other. Netanyahu reportedly barred Gallant from attending a late December meeting with the country’s intelligence chiefs, and the two Likudniks have repeatedly declined to appear before the press together. When Israel’s plans for postwar Gaza, as well as a possible commission of inquiry into the army’s Oct. 7 failings, were raised before the full security cabinet in early January, the session plunged into a shouting match between IDF Chief of Staff Herzi Halevi and far-right cabinet ministers. Gantz and Gallant leapt to Halevi’s defense; Netanyahu stood by as his coalition partners assailed the wartime leader of Israel’s military.

The war cabinet holds regular, highly tense meetings with families of the over 130 hostages still in Gaza. Within this high-stakes emotional maelstrom, “Gantz is somebody who people like to identify with,” one insider who has been present at these meetings said—a sharp contrast with Netanyahu, who often comes across as distant, badgering, or self-concerned. “[Gantz] speaks and he looks like Rabin.” Israel’s always unreliable polls show him as an early favorite for postwar prime minister. But as a key theorist of the failed multi-billion-dollar defensive barrier that Hamas breached on Oct. 7, it is hard to see Gantz transcending his image as an unexciting centrist mainstay, especially at a moment when the establishment he represents has sunk to all-time lows in credibility.

Gallant “is perceived to be very trustworthy, if not as cuddly as Gantz,” the source said of the hostage families’ reactions to the defense minister. “The way he speaks, and as a persona—he’s less lovable. But when he speaks his messages are respected. People don’t start shouting at him. He’s not polarizing. He comes across as someone who’s very professional. It doesn’t go beyond this. People don’t say, ‘oh, we love you.’”

Those familiar with Gallant’s thinking do not believe he wants Netanyahu’s job, though in the unknowable chaos of post-Oct. 7 Israeli politics he might wind up with it anyway. In a post-Netanyahu scenario, Gallant would be one figure capable of holding together a simultaneously chastened and energized secular right. If the war ends with Yahia Sinwar dead and Hezbollah pushed beyond the Litani, more credit would go to Gallant than to Netanyahu or Gantz.

It is possible to see the glimmer of Gallant’s future appeal. If there is anyone in Israeli wartime leadership who evokes a lost era of national power and confidence, it is Gallant, who issues dire predictions to the enemy in the short, grave, punctuated sentences of someone who really means it. “If Hezbollah wants to go up one level, we will go up five,” Gallant declared during a visit to the Lebanese border on Dec. 17, two weeks before an Israeli airstrike killed Hamas political chief Saleh al-Arouri in the Hezbollah stronghold of South Beirut, an attack reportedly carried out without prior warning to the U.S. Hamas fighters who are counting the days until the IDF withdraws from Gaza, Gallant said on Jan. 4, “need to change the count until the end of their lives.”

In these moments, Gallant is a Jewish war chief beamed in from the late ’70s, or maybe from the mid-’50s, or maybe from the time of the Shoftim themselves. Whether that is what Gallant really is relates to the question of what Israel now is—whether Oct. 7 has reawakened an ancient knowledge of the national condition, or exposed everything the country has lost.

In peacetime, Gallant, who is 65, would wake up before dawn and go from his house in Amikam, a moshav near the coastal wine country hub of Zichron Yaakov, to the dock at Sdot Yam to kayak on the Mediterranean—on Saturdays he’d spend three hours on the sea. Surrounding his house is an agricultural plot smaller than a farm but much larger than a garden. “Everything in the area where he hosts his friends is something he did with his own hands, and he’s very proud,” said one occasional visitor. “He does everything himself, everything”—he builds his own furniture, grows and harvests his own fruit and vegetables, makes olive oil from olives he picks himself.

Our work is as urgent as it has ever been.

The monasticism of Gallant’s wartime uniform isn’t a pose. The defense minister can thrive without these distractions and comforts, and possibly without any comfort at all. “How do you know he’s a military person?” asked Nira Yadin, a former Knesset aide of Gallant’s. “Because he can live a whole day on two dates.” As an officer in Shayetet 13 in the runup to the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, Gallant and the men under his command swam distances to the enemy shoreline that a unit comrade of his wouldn’t disclose to me even 40 years later.

Today, Gallant is in charge of prosecuting a multidimensional conflict in which Israel must apply enough concentrated brutality to destroy Hamas, deter Iran, free its remaining hostages, and render the north and south of the country habitable again, all without alienating the United States, tanking Israel’s once-secure international standing, agreeing to temporary cease-fires long enough to rescue Hamas from destruction, or touching off any escalation spirals whose pace and severity Israel can’t dictate. The conflict is also an unprecedented domestic crisis: It is socially and economically crippling for a country of Israel’s size to remain on an indefinite war footing, or endure the ongoing mass displacement of its own citizens and the shrinking of its livable territory.

Gallant is different from his peers in politics and the military. He is more aggressive, more skeptical of the enemy, less in thrall to political fantasy, less oriented toward Western and specifically American obsessions, and less afraid of confrontation. His IDF career, which ended when the superior political maneuvering of opponents in the army sank Gallant’s appointment as chief of staff in 2011, reads like a long and often losing campaign against the national drift Hamas exposed on Oct. 7.

Amos Ben Gershom/GPO; Avi Ohayon/GPO

Still, reversing course requires an era-defining break with the failed assumptions that governed much of Israeli life for the past 30 years, which is something that might prove beyond the ability and imagination of any of the country’s current leaders, Gallant included.

“Gallant when it comes to military operations has always been a hawk. In every operation I saw, he was always the guy who wanted to extend it, or to be more decisive,” said Amir Avivi, a retired IDF general and Gallant’s former colleague who served under Gallant as deputy commander of the army’s Gaza division. “He is exactly the kind of guy you want in a war. He’s a gladiator. The only thing he thinks about morning, noon, and evening is how to destroy the enemy, that’s it.”

Gallant was—and, by all accounts, still is—the kind of good-natured hardass who inspires admiration in the people under him. During a press conference I attended at the Kirya, the Defense Ministry’s college campus-like Tel Aviv headquarters, it was impossible not to focus on his hands, which are massive, veiny, and very likely still dangerous. Gallant has a close-cut, white brow line and absolutely no facial hair. When facing the media he stands with the freakish stillness of a man accustomed to situations where survival depends on total bodily control, never pivoting weight or looking down at notes that he might not even have. He locks his head at an almost imperceptible downward tilt, such that TV viewers will see him in a subtle and unwavering upward stare that draws out an intense pair of unblinking eyes. They are beacons of mortal seriousness burning from the end of a muscular neck, simultaneously trained on the Israeli public, on Yahia Sinwar, and on whatever journalist is questioning him. His cheeks are twin cliff faces; he might not smile again in public, or maybe even in private, until the war’s been won.

Leading militaries train their career officers through a long-established system of service academies, war colleges, and domestic academic programs. But as Avi Bareli, a Ben-Gurion University historian who specializes in civil-military relations in Israel, explained, “professionalism in the Israeli army is problematic. It still has some traits of a militia.” Among them is an ad hoc system of recognizing and fostering leadership talent. In the IDF people of middling ability can advance through cliquishness; an enduring informality allows institutional conformity to fester, since there are no structures in place for ensuring that overly independent thought isn’t punished. “The best military education they’re expected to have is to study in the USA,” said Bareli.

Gallant once opened a talk before an AIPAC group in Jerusalem by saying: ‘Sorry for my poor English. But Hezbollah and Hamas don’t understand English.’

In the decades after the Oslo Accords, the advanced intellectual and strategic training of Israel’s military elite has been effectively outsourced to the United States, through programs like the recently ended Wexner Fellowship at Harvard University’s Kennedy School. Netanyahu is calculatedly American in his style and outlook, and Gantz, military attache to the U.S. from 2005 to 2009, is the kind of pliable army establishment type whom Washington has always seen as a natural ally.

The young Gallant did not get a fancy foreign degree or eye a career in business or politics, working instead as a lumberjack in Alaska when his initial six-year period of active-duty service ended. Gallant did not prepare himself for anything but a life in the IDF, which he treated as his natural home and his entire professional future when he returned to Israel. He once opened a talk before an AIPAC group in Jerusalem by saying: “Sorry for my poor English. But Hezbollah and Hamas don’t understand English.”

In contrast to this gruff public persona, Gallant is “one of the most intellectual people I ever met in the army,” Avivi told me. He is said to be a voracious student of history, with an interest in the Middle East, World War II, Islam, Jewish history, and Zionist history. As with the sometimes-mercurial Ariel Sharon, who pulled off one of Israel’s most fateful reversals at a time when Gallant served as his military secretary, there is a significant side of Gallant’s personality that he shields from his battlefield enemies, his political opponents, and—crucially—members of the press. He gave no real on-record interviews during the first three monthsof the war, and did not talk to me. He seems to believe that amid a multifront conflict and simmering domestic political chaos, excessive outside mediation of his decisions is unnecessary, maybe even counterproductive. “Don’t be confused,” Yom-Tov Samia, a retired general who oversaw the IDF’s southern command between 2001 and 2003 and served with Gallant during three operations against Hamas in Gaza, told me. “The only ones who control what’s happening now are Gallant and the army headquarters.”

Yoav Gallant believed he would be IDF chief of staff from a young age. He was the leader of his local cohort of Tzofim, Israel’s version of the Boy Scouts, and predicted he would go far during his coming army service. Usually only sociopaths share such extravagant future visions of themselves, but Gallant is not a craven egoist. He is instead a prior era’s version of an uncynical patriot. One official who has worked with Gallant described him as an embodiment of eretz Yisrael hayeshana ve hatova—the good old Eretz Yisrael, the secular macho pioneer society that believed itself capable of anything and whose big disillusionments were all in the future. “He is very Zionist,” said one friend. “When he writes something down, at the end there’s always an Israeli flag. Always—always.” Gallant is named after Operation Yoav, the decisive counteroffensive against the Egyptian army in the Negev during the War of Independence, which his father fought in. Both of his parents were Holocaust survivors from Poland—Gallant often talks about his mother’s childhood voyage aboard the Exodus, the Jewish refugee ship that British authorities blocked from landing in mandatory Palestine in 1947. His father, an anti-Nazi partisan fighter in Eastern Europe and decorated Israeli war veteran, died when Gallant was 17, not long before he began his military service.

Once in the IDF, Gallant chose the most difficult possible path for himself, one that all but prohibited him from serving as chief of staff. The head of the IDF had always started out as an army officer. Gallant went to an ultra-selective navy special forces unit with perhaps the hardest training in the entire military: Shayetet 13, the Jewish state’s version of the navy SEALs. I met a Shayetet veteran who served under Gallant in the early 1980s when the future defense minister led one of the unit’s teams, and who himself went on to a senior position in a different branch of the Israeli security state. In those days, a class of 120 candidates would be whittled down to as few as 15. The 18-month training often involved swimming in open water in pitch darkness for hours on end, with no wetsuit and no illumination. “It’s cold in the winter, and you need to do things that are not for human beings sometimes,” said the source, who, like Gallant, looked like he could still handle a solo midnight dip in the pitch-black Mediterranean.

Avi Ohayon/GPO

Gallant was fastidious and hard-charging even by the unit’s standards. The source recalled Gallant’s team returning from a training exercise in the north of Israel late one night. Gallant knew that they were about to drive past a banana farm and announced to the exhausted SEALS that they were taking a brief detour. “He said: We are going to walk in the banana fields, to see if it’s noisy or not noisy. There are banana fields in Lebanon! He was like that.”

“He’s a well-known warrior,” said Amos Gilead, a retired major general and the longtime policy director at the Ministry of Defense. “His whole career is based on serving in the most difficult and challenging units.” In the early 1980s, when Gallant was first on active duty, some of Shayetet’s riskiest operations were commando raids against Palestine Liberation Organization militants operating from their Lebanese safe haven.

For the rising officer corps of Gallant’s generation, the 1993 Oslo Accords were a fundamental break with much of what they’d known. The PLO, the group that Gallant and his comrades had fought in dangerous amphibious night raids barely a decade earlier, became a peace partner and a neighboring quasi-government. Yitzhak Rabin, the man who now touted the moral and strategic wisdom of allowing Yasser Arafat to establish a statelet within Israeli-controlled territory, was one of the most legendary soldiers in the country’s history and a bona fide security hawk. Oslo was a sunny, post-Cold War, almost post-historical project, the impossible peace made real through American unipolarity and humanity’s dawning awareness that war is wrong and futile. Over the next 30 years, much of the Israeli political class—including most of the mainstream right—and nearly the entire senior echelon of the army fell captive to this beautiful and inevitably corrupting dream.

Gallant wasn’t one of them. Harel Knafo, who was Gallant’s chief of staff during his time as head of the IDF’s southern command in the late 2000s, said Gallant “wasn’t fooled by the Oslo Accords. He is not under the American point of view. The two-state solution is the American point of view. It is not the Israeli point of view.”

In the early and mid-’90s, Gallant switched over to the army to head the IDF’s territorial brigade in Jenin, in the West Bank, before becoming the top commander of Shayetet 13. By 1996, it was clear a reinvigorated Palestinian militant movement would be a defining feature of the post-Oslo peace dividend. After a wave of attacks and the killing of a deputy division commander, the IDF decided that control over a more restive and quasi-autonomous Gaza Strip required the attention of a serious senior officer. At the time, Amir Avivi was deputy commander of a division in the north of Israel. Gallant, the army’s incoming Gaza chief, invited him for an interview at his house in Amikam. “He opens the door wearing a T-shirt and sandals, prepares a cappuccino, takes me to his garden, sits and talks about what’s going on in Gaza,” Avivi recalled. “This is Yoav Gallant”—hospitable, serious though also informal within his closely protected private spaces, and able to command immediate loyalty.

As Avivi explained, between 1996 and 2000 “Gallant took a very basic headquarters and made it a real division, with reserve units, command and control—a real buildup of force. He really built up the Gaza division for war, which we knew would start in the year 2000.”

Gallant and his deputies were correct about the looming conflict. The Oslo process wasn’t a prelude to a fast-approaching final peace, but a glide path toward the Second Intifada, which was then the longest, deadliest outburst of violence between Palestinians and Israelis.

In 2002, Gallant became the military secretary to Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, perhaps the greatest and most controversial field marshal in Israeli history. “Yoav really loves Sharon,” a political operative who knew both men well told me. “When he speaks about Sharon, he smiles.” The source expounded on the similarities between the two men. “Both are farmers … both were heroes in the army. Both are very brave, with a lot of sense of humor. Both are very loyal to the people who worked for them. Both are very strict. Both are akshan”—stubborn. “If they believe something, that’s what they do. You can’t move them … Sharon knew every point in Israel. He didn’t need a map. Gallant is the same.” And there was one other, telling similarity: “With both, there is a huge gap between their image and how you meet them one on one. One on one, he’s completely different.”

Former colleagues all say Gallant is looser, funnier, and more cerebral than he appears. “He doesn’t behave at all like a general or a military man,” said Nira Yadin, who worked as Gallant’s press aide at an early point in his political career before becoming a lawyer. She described a somewhat warmer man than Israelis know. “What’s important for him is the background of the person. He asks about family, your army service—the Israeli side of your personality.” Yadin, then a journalist, contacted Gallant when she saw a job opening as his spokesperson in 2015. At first they communicated only through text messages. When they finally met, Gallant, who was then Israel’s construction minister, did not care that Yadin was deaf so long as she could do the job well. “It had no meaning for him,” she recalled.

“He doesn’t speak a lot,” said Harel Knafo. “But you should be with him in the same room where he’s making the decision, and explaining the decision.”

Sharon had similar qualities, which were also at odds with a public image that underwent several inversions. Before the mid-2000s, the general-turned-prime minister had entered history by encircling the Egyptian Third Army in 1973, ravaging Beirut in the early ’80s, and crushing the deadliest terror campaign Israelis had ever faced in the early 2000s. Since the early ’80s, Sharon, legally barred from serving as defense minister over the IDF’s failure to stop the Sabra and Shatilla massacres in Beirut, had been a phantom stalking the Israeli system, which treated the hero of the Yom Kippur War as the sole scapegoat for the setbacks and excesses of the 1980s Lebanon invasion. As prime minister in the early 2000s, Sharon oversaw Operation Defensive Shield, the broadly successful military campaign that ended the suicide bombings of the Second Intifada.

The terrorism campaign and its defeat seemed to vindicate the brutal genius of Israel’s internally exiled war chief. Sharon’s predecessor as prime minister, Ehud Barak, as well as the entire political and security mainstream, believed peace would come through vacating Gaza City and the West Bank’s population centers and working with Arafat. Defensive Shield succeeded through the army reoccupying these places and besieging Arafat’s office in Ramallah. One of the 21st century’s great counterinsurgency campaigns reversed the national demoralization of an unprecedented terror wave. Then Sharon capitulated to the dream-logic of the people whom he’d fought his entire career, just after proving all of them wrong.

Sharon treated Israel’s post-intifada position of strength as a chance to resolve the Palestinian issue on his own chosen terms, beginning with a unilateral withdrawal of all civilians and military forces from the Gaza Strip in August of 2005. No one can remember if Gallant supported the disengagement, though Avivi, who was present at meetings in which Sharon and the country’s security chiefs discussed the move, does not recall Gallant ever opposing it.

The record of the Oslo era suggests that any land ceded to any Arab-governed political entity will rapidly become a new beachhead in a suicidal war against Israel’s existence, a reality Gallant sensed from the mid-1990s. At the same time, it is internally corrupting and perhaps impossible for Israel to rule over millions of Arabs living in places that Israelis have no real desire to conquer and no practical means to hold in the long term. Sharon staked his legacy on this premise when he decided to pull out of Gaza.

One answer to the dilemma of how Israel can protect itself without the political, diplomatic, and moral hazards of governing or depopulating Arab-inhabited lands is a clear policy of deterrence, tailor-made for regional realities. “We are not living in Sweden. We are in the Middle East,” explained the retired General Yom-Tov Samia, a child of Libyan immigrants to Israel and a former colleague of Gallant’s in the army. “And in the Middle East the language and the culture is different. The main points of the language in the Middle East are religion, power, and nonrespect to the human being, meaning that from the leaders’ point of view the people should serve the leader, not that the leaders should serve the people.”

Samia is now an executive in alternative energy. Like Gallant, he makes his own furniture, wooden desks, and tables with glassy colored inlay, though it is hard to imagine Gallant wearing a large Magen David ring. Samia was one of Gallant’s predecessors as IDF southern commander, a theater he oversaw during the peak of the intifada and Operation Defensive Shield, and he served with Gallant as a reserve officer after leaving the active-duty military. During this latest war, Samia has spent his spare time in communities in the north of Israel training and organizing kitot konenut, local civilian protective forces that have had to become much more serious operations, once Oct. 7 exposed the enemy’s intentions and previously unknown gaps in basic Israeli state capacity.

Israel in the 21st century has had the image of a high-tech military superpower, but this is something very different from possessing actual strength. In 2000, Samia told Ehud Barak, who was then both the prime minister and defense minister, that his planned withdrawal of Israeli forces from southern Lebanon could ensure an epoch of quiet only as long as Hezbollah and everyone else on the other side of the border swiftly internalized the consequences of attacking Israel. “I told him, we should use the word baal habayt hishtagea”—“the landlord has gone crazy.”

This concept meant sending the following series of messages north of the border: “Remember, one missile on Kiryat Shmona, I’m going to destroy such and such infrastructure in Lebanon. If you’re going to shoot more missiles on the Galilee, I’m going to destroy the Syrian corps in Lebanon. And if you’re going to continue I’m going to destroy all the, I don’t know, airports, bridges, water, power plants; I’m going to send back Lebanon and Hezbollah 100 years; you will not have electricity, you will not have water, you will have nothing.” Ideally the threat would be executed without any foot-dragging deliberation on the Israeli side. “[We’ll] have a plan in the drawer so the air force commander, once one missile is fired, just opens the drawer and three two one, order, boom. No decisions, no meetings in the government, it’s attack attack attack automatically. And this is the language of the Middle East.”

A generation of Israeli leaders communicated a very different mentality to the enemy. The reality that hardened in its wake has not been especially peaceful. In a drearily familiar paradox of armed conflict, avoiding war made the eventual eruption inevitable, and also worse. “In our language,” Samia said, “we can live with some missiles on Kiryat Shmona once in a while; we can live with the kidnapping of three soldiers in 2006; never mind, it’s OK. [But] then they understand that you are very weak.”

When Gallant became head of the IDF’s southern command in 2005, he put the entire theater on a more active footing. Top generals and Israel’s political leadership thought that the real-world responsibilities of governing Gaza would moderate the Palestinians, perhaps leading to a bright horizon in which the Strip became the Singapore of the eastern Mediterranean. “Gallant said no,” recalled Knafo. “We’re going to wartime.”

When the IDF would not provide the budget he thought he needed, Gallant ordered Knafo to coordinate with other generals so that they could transfer some of their own resources, allowing the southern command to deploy additional observation posts and radar, and hold large-scale exercises. Gallant insisted on the deployment of the new and novel Baron radar system along the Gazan and Egyptian borders, even though the southern command wasn’t budgeted for them. “He told me, I don’t care. Cancel other plans,” said Knafo. “I want these Barons a year from now on all the Gaza Strip. And we did it. We had to fight other commanders. But after it started to be operational, they all thanked us.”

In 2006, Hamas kidnapped the Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit in a cross-border raid. The Islamists seized the Gaza Strip from the Palestinian Authority in 2007, throwing their political foes off of the roofs of high-rise buildings. Rocket attacks grew more frequent and the Hamas arsenal more advanced across 2008. Gallant advocated a solution nicknamed anan kaved within the southern command: “heavy cloud,” the total defeat of Hamas through a full-scale invasion, followed by a lengthy though temporary Israeli reoccupation of the Strip. By the winter of 2008, Israel’s political and military chiefs were persuaded the Hamas attacks required a serious response. Defense Minister Ehud Barak and Chief of Staff Gabi Ashkenazi didn’t want anan kaved but something much more limited and surgical, aimed only at degrading Hamas’ capabilities and ending the rocket fire.

Jack GuezAFP via Getty Images

Israeli war-planners believed they could contain Hamas through meeting operational objectives that now seem ludicrously unfocused, and that were absurd even at the time. “Some of the goals were strange down to funny,” recalled Samia of Operation Cast Lead, the round of Gaza fighting that began in late 2008. “I’ll tell you for example: Goal No. 1, reduce the amount of missiles from Gaza to Israel. That’s a target. So I told Yoav, how many did we have today, 1,000 per day? Let’s make it 950 and we reached our target. It’s reduced!” I asked Samia how Gallant responded. “He was more angry than me. He was shouting as I shout. And they told him yes, this is your mission, along with other funny things. None of them was to vanquish Hamas.”

Cast Lead was Gallant’s masterpiece as a field commander, even if it stopped far short of what he believed was necessary. Six brigades swept across most of the Strip, which the IDF swiftly divided in three. Ten soldiers died in total, four by Israeli fire, meaning Hamas killed as many IDF personnel in a month as it has during single days of this current war. Hamas had no fortified tunnel network and far fewer rockets.

For the next 15 years, the total destruction of Hamas’ Gaza branch remained far outside the mainstream of official thinking. Hundreds of Israelis might die taking over Gaza. Ruling the place was too hard and too costly for Israel to do itself, even temporarily. Perhaps something worse would replace Hamas once the IDF left. Maybe careful and patient engagement with the Hamas threat could be a new and improved form of battlefield victory. A generation of Israeli leaders convinced themselves that financing their enemy was in fact a brilliant means of controlling their enemy. Tolerating frequent rocket attacks was evidence of careful threat management and strategic restraint, as well as the brilliance of Israeli missile defense—only a very strong and very wise country could afford to allow Sderot to live under fire.

The architects of this system of trade-offs, which Ehud Barak and Benjamin Netanyahu both wholeheartedly embraced, were not entirely wrong about any of this. Israel fought no major wars in the 2010s, a decade when the country reached Western European levels of economic prosperity and material comfort, became a global high-tech leader, and made peace with four Arab nations. Israel achieved this without ceding any additional territory to the Palestinians, or even having to talk to them—the last round of even half-serious negotiations was in 2014. Suicide bombings were relegated to an earlier and darker era of national life. The border between Israel and the Hezbollah statelet in Lebanon was quiet for 15 years.

“The real debate wasn’t, do we destroy Hamas,” recalled Ari Harow, who served as Netanyahu’s chief of staff during Operation Pillar of Defense, the 2014 Gaza operation (and recently wrote a book about the experience). “[Avigdor] Lieberman and [Naftali] Bennet did release calls in that vein,” Harow recalled of the fighting. “But to a large extent it was perceived as political posturing. You know we’re not going to take over Gaza, and if you did you’d be more hesitant.”

Ayelet Shaked, a former member of the security cabinet, summed up the national groupthink from her years as a leading Knesset member: “The reality was that Hamas is there and the army said in all those years that in order to eliminate Hamas it will have to pay a very, very high price in casualties,” she told me. “This is what everyone wanted to believe: that we will hit them if they do something, and that we have a very, very sophisticated fence.”

Zohar Palti, the head of Mossad’s directorate of intelligence in the early 2010s, raised the chilling possibility that Israel’s political, defense, and intelligence establishment didn’t merely get Hamas wrong. Pogroms and holocausts notwithstanding, the Jewish state had lapsed into a fatally idealistic view of their enemies’ motives and of human nature in general. “We thought, even with bad guys they have morality, conscience, things like that … the assumption was that if you give them [the chance] to live in a decent way, they’ll be restrained in their behavior …”

“It failed.”

Gallant oversaw the southern command for five years, between 2005 and 2010, an unusually long time for such a position. When asked why Gallant stayed, Knafo invoked the Native American idea of the afterlife as an “endless field of hunting.” Even in his early 50s, Gallant wanted to fight Israel’s most dangerous enemies from as close up as possible. “Gallant believed southern command is the best job in the world.”

If Gallant also calculated that a major regional command was a logical final step to the chief of staff’s chair, he was proven correct in August of 2010, when Defense Minister Ehud Barak overcame their Cast Lead disagreements and named him as the next leader of Israel’s armed forces. Gallant then became the decisive loser of one of the more prescient episodes in modern Israeli political history, one that helped solidify the army and legal system’s growing role in how the country was run, and that showed how the establishment mainstream could punish potential dissenters who had flown too high.

First came the so-called Harpaz Document, also from August of 2010, a forgery that purported to be a public relations firm’s strategy for a mud-slinging campaign by Gallant against his rivals for the chief of staff job—including Benny Gantz, then the army’s second in command. The fake was too sloppy, though: On closer examination, the Harpaz Document was an unintentionally transparent ploy to besmirch Gallant by portraying Gantz and Ashkenazi as the victims of a fake dirty trick, although it might also have been part of a move to pressure Barak, another rival of Ashkenazi, into extending his term as chief of staff. An investigation into the document’s origins was buried under circumstances that were themselves suspicious, with future Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit implicated in the possible coverup. The person who leaked the document to Israeli media, an intelligence officer turned private sector defense adviser named Boaz Harpaz, was reportedly close with Ashkenazi.

The anti-Gallant forces, whoever they might have been, delivered their headshot over a seemingly insignificant issue. News broke that Gallant had built an addition to his property, already a very large one by Israeli standards, on public land in Amikam without obtaining the right permits. Attorney General Yehuda Weinstein told Israel’s Supreme Court that it was unreasonable to promote someone accused of such wrongdoing to so high a position. Barak and Prime Minister Netanyahu canceled Gallant’s appointment in early 2011.

It is now widely believed among Israeli political watchers that Gabi Ashkenazi ran a winning campaign to sink his successor. Though they had disagreed over whether to destroy Hamas in 2008, the differences between Gallant and Ashkenazi were petty, personality driven, and nonideological. “It was a war of the generals. Gallant’s appointment was scuttled because one side of the generals won and one side of the generals lost,” said Avi Bell, a Jerusalem-based political observer.

Gallant had his dream destroyed at the last possible second, thanks to the cattiness and factionalism of a mediocrity-stricken Israeli officer class that was beginning to test its ability to meddle in civilian politics. Members of Gallant’s own club had purged him. Critical issues of state were being decided the cheapest way possible, through absurdist covert media campaigns. Worse still, a chief of staff appeared to have successfully blocked the nomination of his replacement. “This is something that goes to the basics of the control of the elected government over the military,” said Bareli. “Douglas MacArthur was fired for much less.”

Elad Malka (IMoD)/Anadolu via Getty Image; Ariel Hermoni (GPO)/ Handout/Anadolu via Getty Images

Benny Gantz became head of the IDF instead of Gallant. Ashkenazi later became Israel’s foreign minister as a senior member of the Gantz-led Blue and White party. As Israel’s national security quietly eroded, centrist ex-generals sympathetic to Washington’s outlook on the Middle East became increasingly common features of Israeli political life.

What did Gallant learn from all this? Friends and colleagues insist that the experience of losing the chief of staff job did not embitter him, and Gallant’s subsequent record proves them at least partly correct. Over the next decade, Gallant learned how to be a politician, and how to play the Israeli political game so that he wouldn’t be at the receiving end of any future debacles. But in his biggest moment in politics, Gallant treated the forces that destroyed his army career—the politicization of the military and the legal system, the rise of a vindictive and conformist post-Oslo establishment—as factors to be accounted for rather than reversed.

In 2015 national elections, Gallant checked the security box for Kulanu, the new political party of Moshe Kachlon, whose cost-saving reforms to the cellphone industry had made him a popular communications minister and a potential threat to Netanyahu, his former Likud colleague. In a sign Gallant had grown into something of a subtle political tactician, he began angling toward the larger and more powerful Likud almost as soon as he joined Kachlon, becoming a frequent presence at the weddings and bar mitzvahs of the party’s leaders and key supporters. He served as the Likud education minister during the COVID pandemic, a position in which he did not especially distinguish himself.

In late 2022, a Netanyahu-led right-wing block won a four-seat Knesset majority in national elections, creating a stable coalition with the potential to end Israel’s yearslong political deadlock. Netanhyahu’s electoral success was based partly on the manipulation of figures to his right: In the 2022 election, he boosted the neo-Kahanist Otzma party of Itamar Ben-Gvir and Betzalel Smotrich, gained their support for prime minister, and then rewarded them with ministerial positions designed to either neutralize their actual power or expose them as unserious.

With Netanyahu’s majority finally in hand and the entire right seemingly under his control, Likud Justice Minister Yariv Levin launched a sweeping legal reform effort aimed at stripping Israel’s Supreme Court of much of the extra-democratic power it had allegedly seized. Allowing Levin to move forward was the worst miscalculation of Netanyahu’s long political career: Nearly everyone outside of the prime minister’s base of supporters came to view the reforms as a power grab, owing to Netanyahu’s own legal troubles and the perceived illiberalism of the new coalition. More importantly, Netanyahu did not anticipate the establishment backlash, or for that matter the American backlash and Biden administration countercampaign, against any attempt to reduce the court’s reach.

For a significant and powerful group of Israelis, Gallant had rescued the Zionist dream from the dictatorial, messianic schemes of Bibi, Ben-Gvir, and other zealots who were lining up to trample the country’s democracy.

When he was named defense minister in late 2022, Gallant was perceived as a Netanyahu loyalist. But as one of the most respected and least-ideological members of the most right-wing government in Israel’s history, as well as someone who had been socialized within the same military establishment that was beginning to line up against the reforms, Gallant was also a possible weak link in the coalition’s plan. In March of 2023, after meeting with pilots and other specialized officers who threatened to sit out their reserve service if the reforms moved forward, Gallant declared he could not support the package in its current form, and urged compromise with the opposition. In another sign that Gallant had learned the tactics of his old opponents, he waited until Netanyahu was out of the country to make his announcement. Netanyahu then fired Gallant, only to unfire him after a half-million Israelis poured into the streets to protest the move. Gallant’s victory in his faceoff with the prime minister meant a Levin-style judicial overhaul was now politically impossible.

To his critics, and most of all to supporters of Netanyahu, Gallant legitimized an act of mass insubordination and validated the army’s growing role in civilian politics—the exact phenomena that once cost him his shot at being chief of staff. Gallant had the option of telling the reserve duty boycotters that they were legally and morally obligated to defend the State of Israel, a country that was always one botched war away from nonexistence, and that the full force of military justice would fall on anyone who refused. Instead he listened thoughtfully and gave the boycotters what they wanted.

For a significant and powerful group of Israelis, Gallant had rescued the Zionist dream from the dictatorial, messianic schemes of Bibi, Ben-Gvir, and other zealots who were lining up to trample the country’s democracy. Gallant did not view his actions in these grandiose terms. “He felt obligated to take care of the security system,” Yadin recalled.

Perhaps Gallant had figured out how to make it at the top of national politics, waiting until the time was right to join the winning side and single-handedly settle the biggest issue in the country. Perhaps Gallant believed, or has always believed, that the interests of the country and the security system are effectively one and the same, and that the precedent of army officers successfully using their position in the military to influence matters of civilian governance wasn’t that important so long as the IDF itself remained strong and prepared. Maybe he had an honest horror of the reforms, and a justifiable distrust of the prime minister. Whether Gallant acted out of principle or political expediency is hard to discern; where and how he draws the line between the two is an even greater unknown.

In the weeks after Oct. 7, when the security system really did briefly collapse and the IDF proved itself weak and disorganized for several deadly and history-changing hours, Gallant finally had the opportunity to test his long-opposed belief that the Hamas problem could be solved through force. In 2008, soldiers under Gallant’s command had reached the sea in 12 hours, using two attack vectors that cut off the Strip’s major population centers from one another. Fifteen years later, Hamas had turned Gaza into a multilayered armory defended by 50,000 fighters, some of them Iranian trained and armed, many of them indistinguishable from civilians. The number of ground soldiers mobilized for the post-Oct. 7 campaign was far greater than earlier Gaza invasion plans called for—perhaps twice as great, according to Palti, the former Mossad intelligence directorate chief. The IDF undertook a patient advance from footholds in the north of Gaza, rather than a swift multipronged invasion.

But the enemy had also adjusted. By mid-December Hamas fighters were no longer wearing any clothing that marked them as militants—they’d stopped exhibiting such combat basics as tactical pants or military footwear, and often moved in groups of fewer than 10. “The notion of them standing and fighting has been erased,” explained one soldier with knowledge of operations in the Strip. Hamas’ battle tactics are now based on avoiding any face-to-face confrontation with the IDF—the extensive physical damage in parts of Gaza City is the result of Hamas’ success at “mousing,” or moving its fighters between interconnected structures without using easily spotted ground-level entrances. Killing an enemy that’s “mousing” means destroying five buildings instead of one, which is something the IDF can do exceptionally well now. Ground troops can call in highly precise airstrikes in as little as five minutes. “Technically there is unprecedented excellent cooperation between ground forces, air forces, and intelligence,” said Amos Gilead, the retired general and former senior Defense Ministry official.

Another way of looking at this is that jet fuel and advanced firepower have to be expended to kill numerically insignificant numbers of enemies. The damage is costly, both to Israel’s image and to whoever will have to pay for rebuilding the Strip. Surviving fighters can retreat to a tunnel network that is broader, deeper, more fortified, and more booby-trapped than Israeli war planners anticipated.

There is no easy solution for the tunnel problem. As one soldier explained to me, flooding the tunnels with sea water isn’t enough to destroy them or even to make them inoperable, but it at least forces Hamas to waste its fuel reserves pumping the tunnels, which is done using very loud generators. But then one of the many perversities of this war—one that Gallant and his colleagues in the war cabinet have been powerless to reverse so far—is that Israel is expected to facilitate the delivery of fuel and other dual-use items into Gaza, some of which will be used to power the pumps.

In three months, Israel has killed or captured perhaps 10,000 enemy fighters, including many of Hamas’ major field commanders in the Gaza Strip; pacified most of Gaza City, captured certain population centers in the south and central Strip, freed a little under half of its hostages and proved it can maintain large-scale military operations for months at a time without an internal or diplomatic collapse. Aside from all the dead and kidnapped Jews, the most significant enemy accomplishment of the war has been the ongoing depopulation of the north and south of Israel.

In a war of theological fantasy in which one side conceives of every success and every sacrifice as part of a thousand-year march to paradise, it will not matter if Sderot and Kiryat Shmona recover their pre-conflict populations. It will not even matter if they become as large as Tel Aviv one day. Israelis fight on short time scales imposed by the basic realities of having to maintain a functioning society at first-world standards. In contrast, the Palestinians, whose social functioning is underwritten through money and services that the U.S., the EU, the U.N. and of course Israel mostly provide, have now achieved a taste of what they’ve dreamed of for generations. Every additional day the north and south of Israel sit empty proves that their hopes of a cleansed homeland are not so insane. That Hamas and Hezbollah could chase a quarter-million Zionists from their homes for three months and counting—that it could turn the southern kibbutz belt, a place that had stood for a uniquely Israeli agrarian ideal, into a war zone—is a fact that will feed the violent dreams of people not yet born.

Can any official of any Israeli government change these basic realities? Do future Israeli leaders have any choice but to change them if the country is to survive? Many different concepts failed on Oct. 7: Hamas could not in fact be bribed into good behavior, actually existing Palestinian nationalism did turn out to be eliminationist, Israel’s high-tech defensive systems actually could be breached through low-tech means, and the United Nations Works and Relief Agency, Qatar, Hamas and Israel’s other subcontractors and co-managers of the Gaza problem hadn’t extricated Israel from the Strip but had instead set the conditions for a massacre. The concept that failed on Oct. 7 of most relevance to Gallant’s job was the idea that Palestinians and their Iranian patrons could be fought like any normal enemy which was accountable to battlefield realities, rational deterrence, and its own governing obligations. In the summer of 2023 Israel agreed to allow the development of Gaza’s maritime gas field, a move that would have enriched Hamas authorities in the Strip. The number of Israeli work permits issued to Gazans climbed from 2,000 in 2021 to nearly 20,000 by Oct. 7. The attackers used permit-holders as advance scouts for their massacre.

Amir Avivi, Gallant’s former colleague, is the founder of Israel’s Defense and Security Forum, a group of 2,000 retired security officials, most of whom are on the more hawkish, right-wing end of the Israeli spectrum. Three years ago, the organization released a national security assessment warning that an eruption was coming. “Our enemy is ready for war, our national security concept has lost relevance. We rely on deterrence, we are not deterring anybody. We rely on alerts but we don’t have an alert. So: We have no choice but to conquer Gaza.” Avivi showed me a picture of Gallant sitting in the front row of the report’s launch event. “Gallant was shocked,” Avivi said. “He didn’t even speak.” I asked Avivi if he thought Gallant shared the group’s grim conclusions. “If he thought that, he should’ve prepared for that,” Avivi replied.

Oct. 7 destroyed many of the comforting fictions of Israeli life. After 14 years in power, it is clear that the core principle of the Netanyahu era, which both backers and opponents of the prime minister had come to unconsciously accept, is that as long as Israel can maintain its bourgeois living standards, its innovative edge, and its appearance of strength and stability, the country’s failure to make meaningful choices could ascend to the level of a higher ideal. The problems could stop being problems if life stayed good enough and safe enough. But billion-dollar tech exits, flights to Dubai, and long stretches of quiet and prosperity did nothing to weaken the enemy. Somewhere between 3,000 and 5,000 Gazans broke into Israel using little more than bulldozers and pickup trucks, proving that the country’s eroded deterrent power had made its technological superiority irrelevant. A fatally comforting theory of a normal and settled existence couldn’t survive the army’s failure to scramble support for communities being massacred.

During its long intermission of relatively unharassed national success, Israel was in fact an advanced society blindly hurtling toward catastrophe. It increasingly appears to be a feature of such societies that they reflexively dismiss the possibility of catastrophe until it happens, even though history demonstrates that large numbers of people, and especially members of elites, often get basic aspects of their reality massively wrong. Individuals have a similar capacity for self-deception, and just as strong and uncritical a belief in the necessary rectitude of their own analysis.

That Hamas and Hezbollah could chase a quarter-million Zionists from their homes for three months and counting is a fact that will feed the violent dreams of people not yet born.

Yom-Tov Samia recalled a conversation he had with Ariel Sharon during the runup to the Gaza disengagement. Samia advised that Israel carry out a gradual withdrawal that left a temporary residual force inside the Strip. “Don’t run away in one night like Ehud Barak did in Lebanon,” he cautioned. Samia said he received “an unserious answer: ‘If we will stay there, they will call us occupiers,’” Sharon told him. “Well, I was very surprised. I told him, you know that as long as we are in Tel Aviv and Ramle and Lod and Jaffa and Haifa, we are occupiers … ‘Occupier’ is our second name.”

By the end of his career, Sharon, a last living avatar of a time when Israel won wars and flexed its power without mercy or apology, had lost sight of what had once been obvious to him. Gallant, another potential national rescuer who harks back to an earlier era, has the chance to correct the mistakes of his mentor, beginning with that rapid flight from Gaza. As one Israeli security official explained, “We have no interest in controlling Gaza. We are going to take the ’05 disengagement and redisengage to a whole new level.” A political consultant familiar with Gallant’s thinking elaborated on what this might mean. The defense minister does not believe any Arab state wants to have any role in governing Gaza, and knows Israelis would never trust a peacekeeping force from the EU with their security. Gallant is said to favor a post-conflict occupation, after which Israel, with the help of the U.S., Egypt, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, will leave the Strip to a “serious, honest, powerful Palestinian that can lead Gaza to the next step … But if you ask me if he knows for sure he can find someone like that? I don’t know.”

Two associates of Gallant’s stressed to me that since the start of the war, he has spoken with U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin on almost a daily basis. It is of course important to keep one’s primary sponsor and weapons supplier happy, but the assistance comes at the expense of Israel’s strategic freedom. In a joint news conference in Tel Aviv on Dec. 18, Austin stressed the need for Israel “to transition from high-intensity operations to lower intensity and more surgical operations,” called to “increase the flow of humanitarian aid into Gaza,” and restated the U.S.’ belief that it was best for both Israelis and Palestinians to “move forward toward two states living side by side in mutual security.” In addition, Austin said, “we’re working to ensure that this conflict does not escalate beyond Gaza,” broadcasting the questionable Washington assumption that the best way to contain the war is by openly telling Hezbollah (and Iran) that the U.S. doesn’t want Israel to retaliate too strongly against their daily attacks. “Hamas does not speak for the Palestinian people,” Austin said, which is something very few Israelis now believe.

In essence, Austin said Israel must continue following the prior failed concept, however counter to Israel’s national interests it might be, and also accept something akin to America’s varyingly successful counterterror doctrine, which dictates a shift from large-scale military operations to surgical special forces strikes to the so-called “over the horizon” posture meant to justify the U.S. flight from Afghanistan. In return for all this, Gallant cracked the closest thing to a smile he’d allowed himself in public in months, vigorously shook Austin’s hand, and thanked him for his help in English.

“Israel will not govern Gaza’s civilians,” read a Jan. 4 postwar plan for Gaza issued in Gallant’s name alone. “Gaza residents are Palestinian, therefore Palestinian bodies will be in charge.” At some future point, a “multinational task force … led by the U.S., in partnership with European and regional partners” will be responsible for the Strip’s “rehabilitation.”

At one of the press conferences I attended, Gallant spoke one sentence in English. “Israel will take any measures to destroy Hamas but we have no intention to stay permanently in the Gaza Strip,” he said. He conceded this crucial point on the conflict’s end-state in a way that made it clear he is obeying someone else’s demand, whatever his personal views might be. Gallant issued a nerve-rattling surrender-or-die ultimatum to Hamas, and then explained, during the question and answer, that a strong Palestinian economy in the West Bank was in Israel’s best interest, and that guest workers in the territory should be allowed back into Israel after a long post-Oct. 7 suspension of permits because “99% of Palestinians aren’t terrorists.” This was something even more disorienting: A statement in Hebrew that seemed calibrated for American ears. Lloyd Austin’s ears, perhaps.

Had Gallant accepted the American outlook on the war, or was he merely appearing to accept it in order to buy time for the soldiers battling in Gaza, an hour’s drive from the Kirya? Was it a sign of incoherency or of true political sophistication that he could promise death to Hamas fighters in one language and signal a Washington-friendly outlook in another?

Avi Bareli, the Ben-Gurion University historian, believes Gallant will say no to the U.S. if it ever demands an end to the war before Hamas is defeated. If the two allies ever reached a true impasse, Gallant is the kind of man who could make Tony Blinken or Lloyd Austin fly home from Tel Aviv empty-handed. “The guts, he has,” Bareli told me. “But what do you say after you shut them down? It’s not a matter of objective will. It’s also a matter of subjective ability.”

In the end, Gallant has to have a strategy that’s worth the trouble of a crisis with Washington, one that dismantles Hamas’ Gaza statelet, pushes Hezbollah far off the northern border, and replaces American assurances with hard-power projection that Israel’s enemies actually fear. It would not be surprising if Gallant has no ready answer to this dilemma. No Israeli leader in the 21st century has had one.

In early January, Gallant finally gave his first exclusive on-record interview of the war, to The Wall Street Journal. The defense minister showed a trademark flash of quotable bellicosity: Hezbollah “can see what is happening in Gaza,” he said. “They know we can copy-paste to Beirut.” Gallant has used a similar line in meetings with soldiers for much of the war. In Israel, the Journal interview was newsmaking for his discussion of imminent, less intense “phases” of the operation, which drew sharp criticism during a closed-door meeting of Likud Knesset members on Jan. 8. Opponents of Gallant—supporters of Netanyahu, in all likelihood—leaked a version of Gallant’s reply, where he said that it would be the army, and not “the women of Sderot and Ofakim,” two cities near the Gaza border, who would decide on the course of the operation.

Had Gallant blundered, losing control in front of his biggest political opponents, who are within the Likud itself? Maybe these were the unfiltered words of someone who doesn’t care about being popular or diplomatic or sounding all that enlightened so long as Israel could fight its enemies and win. Maybe he had overcome his political instincts and made a thrilling statement of actual principle, harking back to his time as a proud commando fighting on behalf of a stronger and more confident country with smaller margins for a failure.

The icons of Israel’s past had to force their way through and above the chaos around them because they had no other choice. Maybe Gallant—who has called the fight he is now leading “a war for a future for the Jewish people”—knows he doesn’t have a choice either.

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.