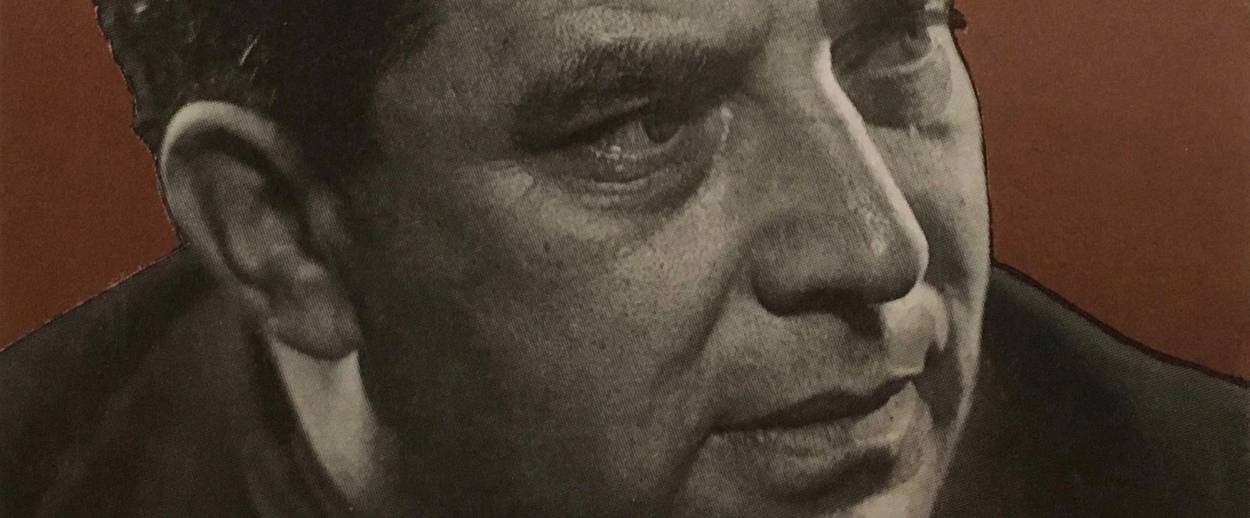

Lev Ginzburg, Soviet Translator

The story of a Jewish Germanophile who became a Soviet investigator of Nazi crimes

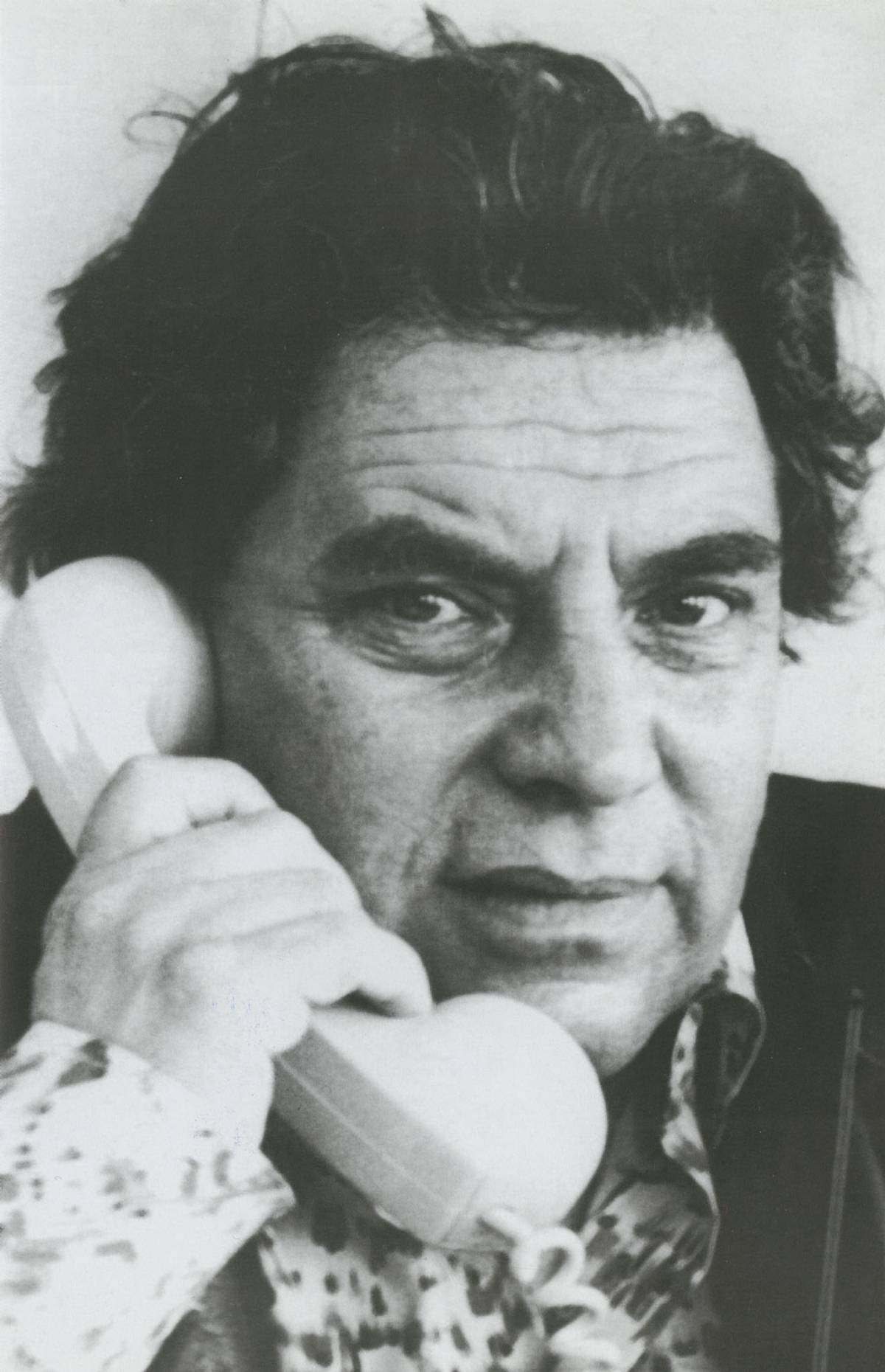

The Jewish-Russian writer Lev Ginzburg (1921-1980) wore several professional hats: a literary translator of poetry from German into Russian; an essayist with a focus on the postwar Germanys; an investigator of Nazi crimes abroad and at home. As chairman of the Translator’s Section of the Moscow Branch of the Union of Soviet Writers and as a Jew trusted to make trips to the West, Ginzburg was a member of the Soviet nomenklatura. He was, one might say, an official Soviet Jew.

The shadow of Ilya Ehrenburg (1891-1967), a senior contemporary, hovered over Ginzburg’s career. Both wrote at length about Nazi crimes and the Shoah; both were poetry translators, political polemicists and sworn anti-Fascists. Both enjoyed their greatest popularity at home when they functioned as Soviet messengers abroad—Ehrenburg in the 1940s and 1950s, Ginzburg in the 1960s. But there was a stark contrast between these two Jewish-Russian authors. In Ehrenburg’s life and writings, the passionate Francophilia—the legacy of his Parisian youth, his intimacy with the international avant-garde—countered the virulent Germanophobia of his wartime articles. During World War II and the Shoah, Ehrenburg’s Germanophobia of both the “Kill [the German]!” variety and of the Black Book fame became a concordant expression of his Russianness, his Jewishness and his Sovietness. Through the first half of Lev Ginzburg’s career, his Germanophilia—and, one might ruefully add, his GDR-philia—kept his writings about WWII, Nazism, and neo-Nazism from becoming artistic texts. Only at the end of his life did Ginzburg produce a work that could stand up to some of Ehrenburg’s best wartime essays and his memoir People, Years, Life, an eye-opener for Soviet readers in the 1960s. In Ginzburg’s novel-essay “Only my heart was broken …,” finished in 1980 and posthumously published in 1981, his Germanophilia implodes, the poet’s heart breaks, and Jewish memory bleeds through the pages of a Soviet writer’s confessional narrative.

Lev Ginzburg was born in Moscow in 1921 to a family of Jewish intelligentsia. Ginzburg’s mother came from Libava (now Liepāja), where she and Ginzburg’s father were married. Wartime refugees, Ginzburg’s parents and their clan moved to Moscow in 1915. If one takes stock of the survival of cultural Germanophilia among Soviet Ashkenazi Jews, then the origins of Ginzburg’s family in Kurland might help explain his own ardent love of German language and culture.

Studying German and writing poetry since childhood, Ginzburg attended the literary seminar at the Moscow Palace of Young Pioneers, directed by the Jewish-Russian poet—and legendary shiker—Mikhail Svetlov. Ginzburg reminisced that

the German language was popular in Moscow at the time. It amounted to being the language of anti-Fascism, the language of Comintern, the language of Roter Wedding and Floridsdorf. It was studied in school much more commonly than any other foreign language. … Waves of German language also wafted in from the songs of the young Rot Front bard Ernst Busch—he sang them in Moscow before leaving, as part of an international brigade, for the war front in Spain.

Ginzburg entered the Institute of History, Philosophy, and Literature (IFLI) in the fall of 1939. A month later, he was drafted into the army, serving for six years in the Far East and joining the Communist Party in 1945, the year he saw military action against Japan. Only in December of 1945 did Ginzburg finally visit Eastern and Central Europe, where he accompanied a Soviet general who brought him along to get impressions. Ginzburg traveled from the Far East via Poland to Germany. The trip, and especially a visit to Warsaw, was Ginzburg’s first face-to-face encounter with the aftermath of the Shoah.

From the late 1940s until his death in 1980 Ginzburg’s close friends were the writers Yuri Trifonov and Iosif Dik, both of them children of mixed marriages between Communist Jews and Communist Slavs. (Ginzburg married Iosif Dik’s sister, the half-Polish, half Jewish-Romanian Bibisa Dik-Kirkillo). As a translator, Ginzburg was encouraged by the dean of Soviet literary translators Samuil Marshak, who had published Zionist poetry in his youth. By the early 1960s, Ginzburg had emerged as a leading poetry translator from German. His contributions included translations of Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, German baroque poetry (especially Martin Opitz, Paul Fleming, and Andreas Gryphius), Schiller’s drama Wallenstein’s Camp, German poetry of the clerici vagantes, and German folklore (Reineke Fox). His translations were collected in a number of books, including German Folk Ballads in L. Ginzburg’s Translations (1959), Words of Morning and Consolations: German Poetry of the Thirty-Year War, 1618–1648, Translated by L. Ginzburg (1963), Pages of German Poetry Translated by Lev Ginzburg: From Vagantes Lyric to Poets of the GDR (1970), Wheel of Fortune: German Poetry Translated by Lev Ginzburg (1976), and From German Poetry. X-XX Centuries. L. Ginzburg’s Translations (1979). Ginzburg the translator was omnivorous. He championed poets of the GDR, sometimes exaggerating their talents and significance. In 1967, Ginzburg wrote a preface to Passages of Time, an important anthology of “younger German-language poets from the FRG, Austria, Switzerland and West Berlin,” to which he contributed the first Russian translation of Paul Celan’s “Todesfuge” and thus introduced Soviet readers to European poetry about the Shoah.

Contemporaries offer diverging accounts of Ginzburg’s gifts as a translator and of his position in the Soviet cultural establishment. Some contemporaries have charged Ginzburg with carrying out ideological missions abroad. Others have referred to him as the head of the “Jewish translators’ mafia” (this sentiment was particularly resonant among the ultranationalist Russian wing within the Union of Soviet Writers). Settling scores with Ginzburg, the Moscow translator Evgeny Vitkovsky dubbed him “a saw blade virtuoso.” In Vitkovsky’s words, “Ginzburg’s method permitted a doubling and trebling of the original’s lines in translation: for example, … Paul Celan’s ‘Death Fugue,’ just over thirty lines in the original, [became] a poem of almost one hundred lines; the length of almost each of the fragments of Parzifal … is increased at least by twofold.” Consider the testimony of the late St. Petersburg author and translator Viktor Toporov, whose mother, a defense attorney, represented Joseph Brodsky at the scandalous trial of 1964: “He was a talented translator. Diabolically talented. … Ginzburg was in possession of only one [translator’s creative] template (which he most brilliantly realized in the poetry of vagantes and Schiller’s early lyrical poetry), but he possessed it with an unsurpassed virtuosity.” The poet Inna Lisnyanskaya, daughter of a Jewish father and an Armenian mother, described Ginzburg as “an ordinary … functionary.”

I met with Lisnyanskaya and her husband, the Odessa-born poet and translator Semyon Lipkin, on a frosty clear day in January 2000. Over coffee in Peredelkino, a writers’ colony outside Moscow, where many Soviet writers had dachas and where Pasternak lived and is buried, Lisnyanskaya and Lipkin reminisced about the scandal surrounding Metropol, an unsanctioned literary anthology that was published in the United States in 1979. Both Lisnyanskaya and Lipkin participated in Metropol, and both resigned from the Union of Soviet Writers to protest the official ostracism of some of the anthology’s contributors. According to Lisnyanskaya, the leadership of the Union of Writers dispatched Ginzburg as its “emissary”: “He wanted us to write some sort of an [apologetic] letter.” When the couple refused, Ginzburg lost his temper and allegedly said this about the way Lipkin and Lisnyanskaya expressed their Jewishness: ‘What is this all supposed to mean anyhow? One goes to synagogue, the other to church …’”

In the post-Soviet years some of the former official liberals within the Soviet cultural apparatus have suggested that the deliberate choices Ginzburg made as a translator (such was his obsession with the Thirty-Year War or his discovery of Celan for the Soviet reader) and as a writer about Fascism were forms of protest against totalitarianism and anti-Semitism not only in Germany alone but also at home in the USSR. In fact, Ginzburg’s path as a translator of German poetry cannot be understood apart from his career as a writer about the legacy of Nazi war crimes and genocidal atrocities. The lists of Ginzburg’s books about Nazism and neo-Nazism starts with The Ratcatcher’s Pipe: Writer’s Sketches, 1956–1959 (Moscow, 1960).

Is The Ratcatcher’s Pipe a text of Shoah memory, and, more specifically, a text of Soviet memory of the Shoah? Only to a degree, although one finds in it a chapter entitled “Buchenwald or Weimar?” in which Ginzburg describes the 1958 Bayreuth trial of Walter Gerhard Martin Sommer, the sadistic executioner of prisoners in Buchenwald. The book also showcases a chapter about Anne Frank’s story and diary. The word “Jew” comes up several times, but it’s not a book about the destruction of European Jewry by Nazis. In its thrust, The Ratcatcher’s Pipe is about the living and regrouping legacy of Nazism in the Federal Republic of Germany and the alleged triumph of the German Democratic Republic over its past. Many of Ginzburg’s optimistic pages about the GDR read like propaganda and lack the wisdom and depth of his best prose.

Ginzburg titled his second book of nonfiction The Price of Ashes: German Sketches (Moscow, 1962). A series of essays about Adenauer’s Germany, it already marks a transition to writing about Shoah memory.

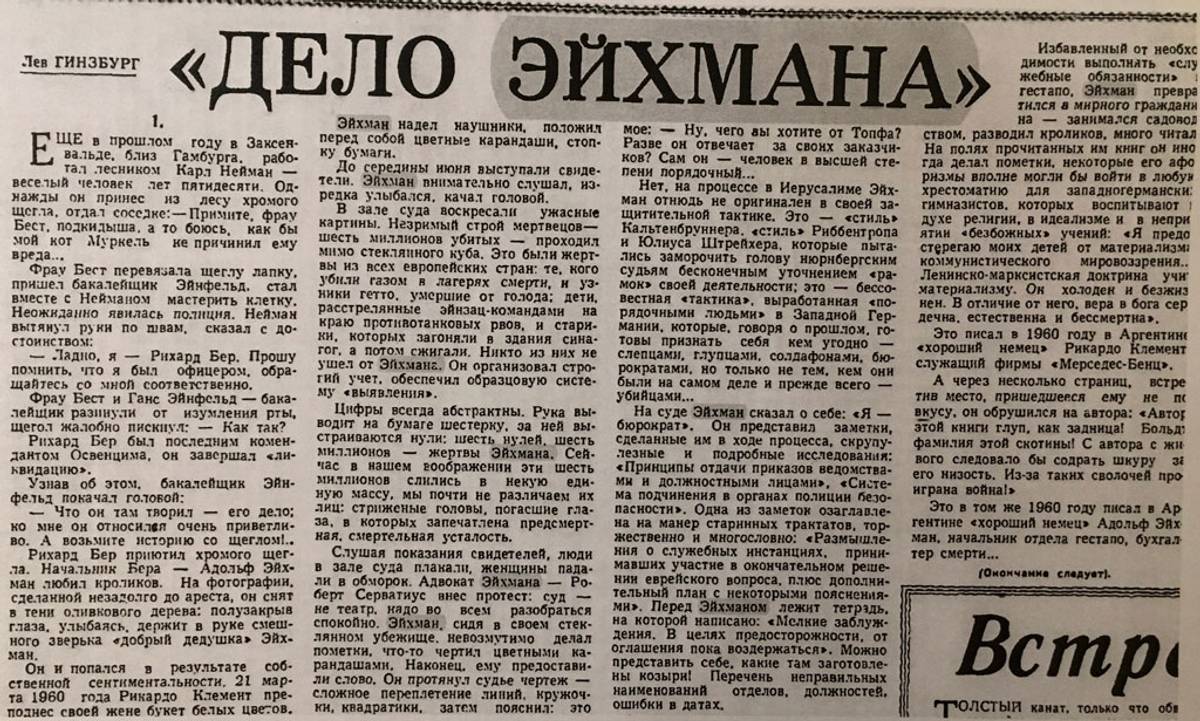

Traveling across the FRG and visiting its cities and towns, including Dachau, is both a goal of Ginzburg’s literary research and a pretext for writing about the presence of former Nazi officials, be it Gen. Adolf Heusinger or the jurist Hans Globke, in West German society and government apparatus. A chapter titled “The Eichmann Affair” forms the moral center of Ginzburg’s book. In addition to “The Eichmann Affair,” Ginzburg addressed Adolf Eichmann’s crimes and trial in two other chapters, “The Price of Ashes” and “A Cause for Anxiety.” Sections were serialized in the newspaper Literaturnaya gazeta (Literary Gazette) and the political magazine Novoe vremya (New Times).

Ginzburg’s publications of 1961-62, when the USSR still maintained diplomatic relations with Israel, amounted to the most extensive Soviet treatment of the Eichmann affair. This is particularly important, given the pathological paucity and spottiness of the coverage of Eichmann’s arrest and trial in the Soviet press. For example, on 12 April 1962 Pravda ran a three-liner on page 6, under the rubric “In Brief”: “Yesterday the trial of the major Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann opened in Jerusalem.”

In light of the dearth of information in the Soviet mainstream, the question of Ginzburg’s sources (which he rarely acknowledged) becomes especially intriguing. In October 2017, as I was researching this story, I turned to the Israeli historian Nati Cantorovich, author of pioneering research on the coverage and reception of the Eichmann trial in the USSR. Cantorovich surveyed the complete runs of central, regional and provincial Soviet newspapers for 1961-1965—a colossal task. His preliminary research revealed no evidence of a Soviet journalist in the courtroom. Cantorovich explained, in an email, that “the other Eastern Bloc countries sent their reporters to the trial (Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary) or decided to hire a local employee (Bulgaria and Yugoslavia). The 1000-page file of the [Israeli] Foreign Ministry contained no mentioning of any Soviet reporter, at least during the period of pretrial and shortly after it started.” Cantorovich allows the possibility that Soviet diplomats attended the trial as “private observers.” It’s my sense that, in addition to the reportage by Eastern Bloc journalists, Ginzburg relied on the coverage of Eichmann’s arrest and trial in the West German press and also had access to dispatches by Western news agencies and other information sources that were considered classified by Soviet standards.

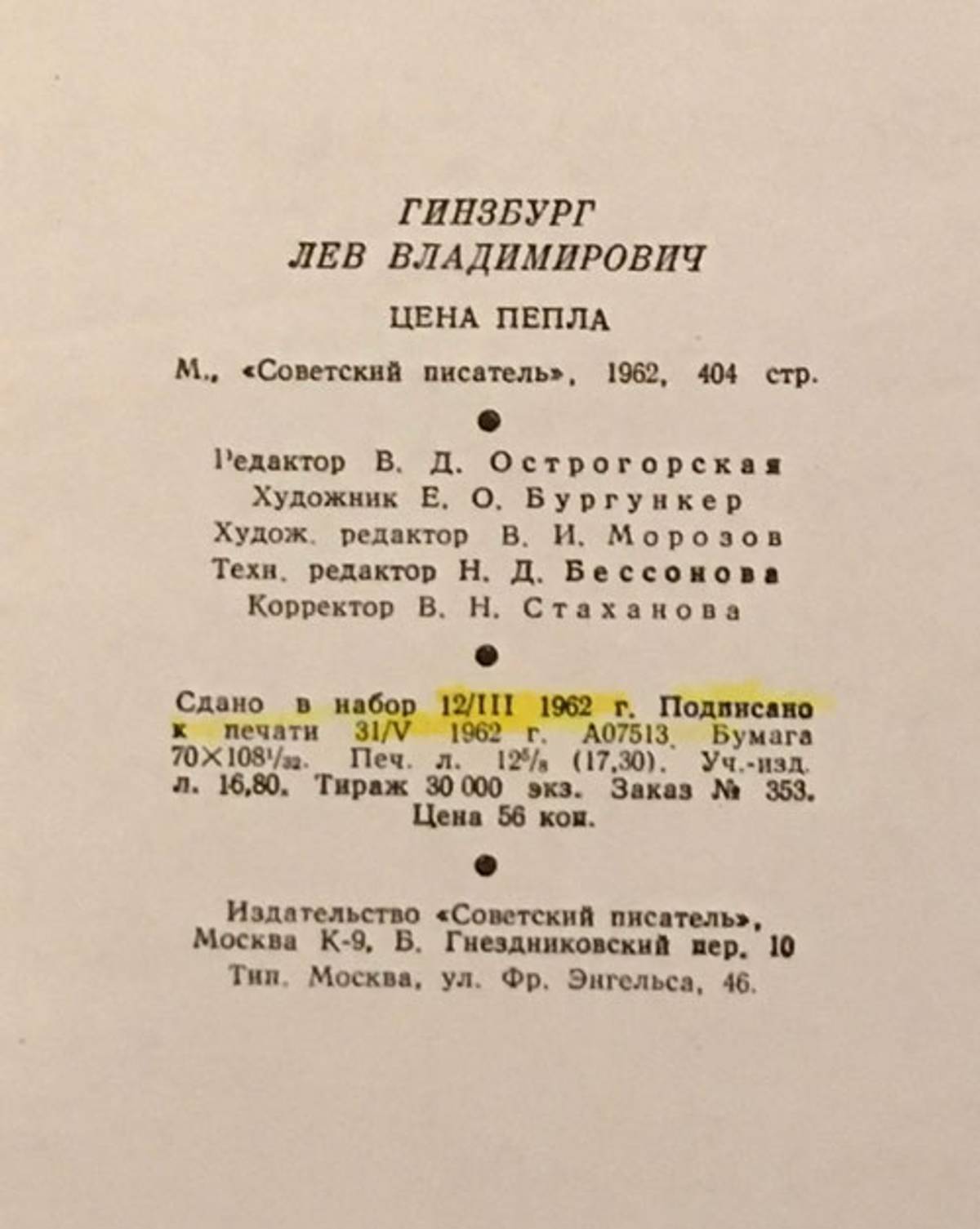

Found guilty of crimes against humanity and the Jewish people and of war crimes, Eichmann was sentenced to death on 15 December 1961 and executed on 31 May 1962.

Ginzburg’s book was officially “signed into print” on the same date when Eichmann was executed by hanging. This circumstance is most significant as it indicates that Soviet censors and publishing executives were waiting for the outcome of the trial before they would allow the publication of 30,000 copies of Ginzburg’s book.

Some aspects of The Price of Ashes would deter the scrupulous reader unfamiliar with the Soviet context of the early 1960s. For instance, Ginzburg refers to Margarete Buber-Neumann, author Als Gefangene bei Stalin und Hitler (1948, in English Under Two Dictators: Prisoner of Stalin and Hitler), as a “renegade,” while the index Eichmann appended to his recollections is said to include “traitor-Zionists” (Ginzburg’s language, not Eichmann’s). Was the dose of Soviet Cold War propaganda and Soviet anti-Zionist rhetoric Ginzburg’s price of ashes, the price he had to pay for being able to write and publish about the Shoah?

Differences of political context notwithstanding, Ginzburg’s lengthy literary treatment of the Eichmann trial invites a comparison with Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), originally serialized in The New Yorker in 1963 and then published as a book. Despite criticism of the handling of the Eichmann trial by the Israeli government and of Israeli relations with the Federal Republic of Germany (“Ben-Gurion committed an act of betrayal not only in respect to the cause of peace but also the Jewish people”), Ginzburg wrote poignantly of the details of the trial, of the Yad Vashem memorial, and of the address to the court, in the name of “six million accusers,” by Israel’s attorney general Gideon Hausner. Ginzburg concluded the chapter on the Eichmann trial with this appeal: “We must not forget this, we who have been participants of the great liberation mission. There is a debt—to those who perished, to those who are living, and to ourselves—to guard the fruits of the victory, not to allow the profanation of all that was fought for and saved for a price of blood, price of ashes …” Here “we” refers both to the collective “Soviets” and the collective “Jews.”

Ginzburg’s next book, Abyss: A Narrative Based on Documents (1966), took the creation of Soviet Shoah memory to a new level.

Abyss was Ginzburg’s report on the October 1963 Krasnodar trial of Nazi collaborators in the Soviet Union, at which nine defendants, all of them former auxiliaries of SS-Sonderkommando 10A of Einsatzgruppe D, were found guilty of war crimes, sentenced to death and executed. This was in fact the second such trial in the southern Russian city of Krasnodar; at the historic 1943 Krasnodar trial, 11 auxiliaries had been found guilty, eight of them publicly hanged at the conclusion of the proceedings.

Tremendously successful, first serialized in Znamya (Banner) monthly magazine, then published as a book twice in 1966 and reprinted in 1968, Ginzburg’s Abyss earned praise in leading Soviet publications. Both Konstantin Simonov, who had been Stalin’s favorite frontline journalist during World War II, and Yuri Trifonov, who had already emerged as one of the leading Russian-language novelists of his and Ginzburg’s generation, published rave reviews of the book. Translations into a number of languages, including Hungarian, Italian, and German, followed. Ginzburg’s Abyss was serialized in the Munich-based magazine Kürbiskern (Pumpkinseed). Partially in response to the publication of Ginzburg’s Abyss, the office of the public prosecutor in Munich reopened a criminal investigation of the activities of one of the book’s characters, Dr. Kurt Christmann, chief of SS-Sonderkommando 10A in August 1942-July 1943, who had already been charged in absentia at the July 1943 Krasnodar trial and whose crimes were revisited at the October 1963 Krasnodar trial. After the end of the war Christmann had fled to Argentina but in 1956 he returned to Munich, where he built a real estate business and was living in the community.

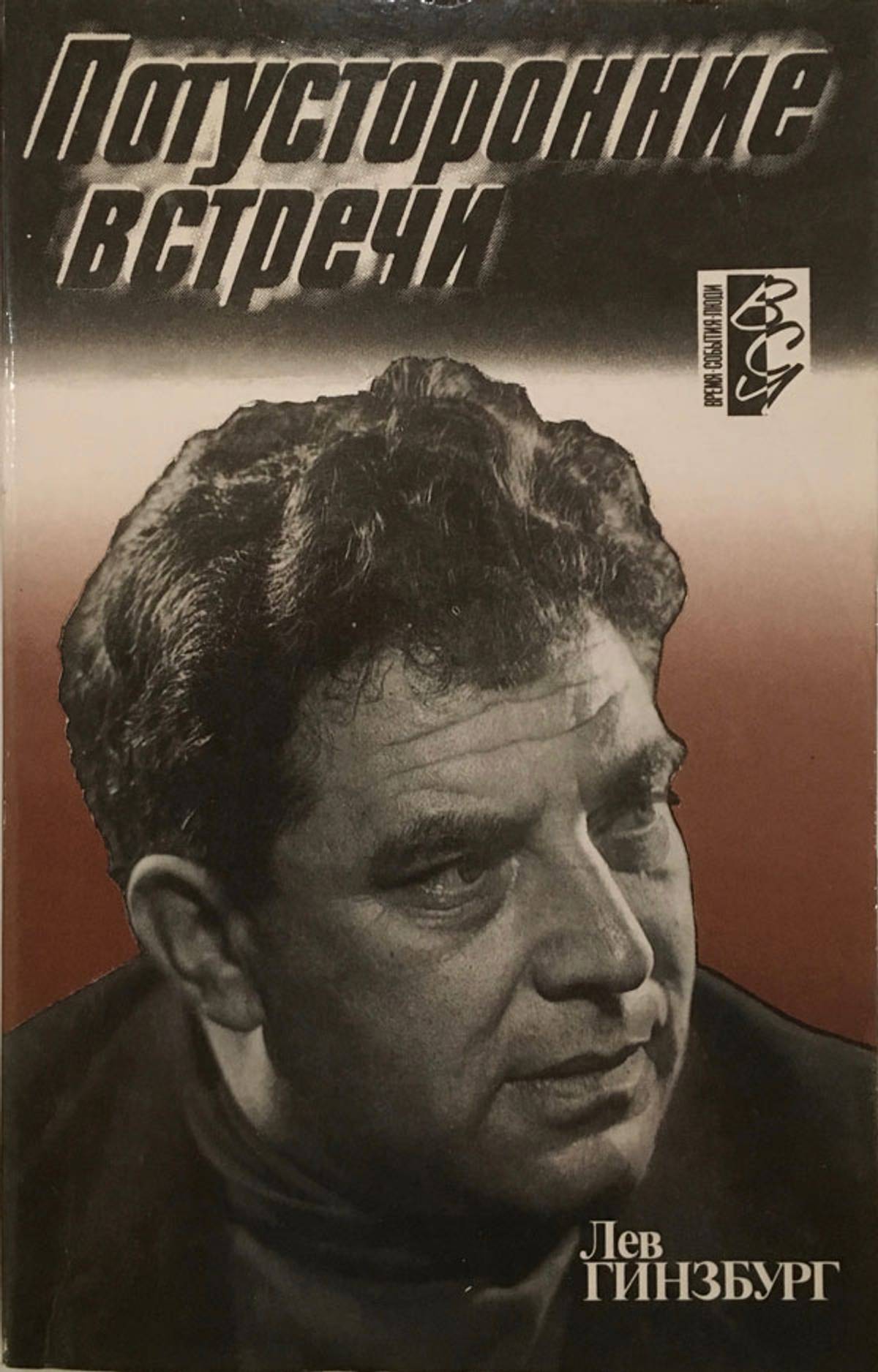

Ginzburg gave his next book, Otherworldly Encounters, the subtitle From a Munich Notebook. The Nazi criminal that bridged Abyss and Otherworldly Encounters was none other than Kurt Christmann. However, Ginzburg’s ambition was to meet face to face with some of the surviving top-tier Nazi leaders and with those who had known them intimately. Ginzburg enjoyed phenomenal freedoms, phenomenal for any Soviet writer and especially so for a Soviet Jew. Having taken a number of trips to West Germany in the 1960s, he reported on his meetings and conversations with Albert Speer, Baldur von Schirach (former leader of the Hitlerjugend), Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht (Nazi minister of economics in 1934-1937), Hermann Esser (member of the National Socialist Party No. 2), and also with Eva Braun’s sisters, Himmler’s son-in-law, and others. At the end of 1969 Otherworldly Encounters was serialized in Moscow monthly Novyi mir (New World)—still then the most progressive Soviet literary journal, where Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich had been published in 1962. Excerpts were printed in newspapers and journals of the Eastern Bloc countries. On the initiative of the distinguished actor and director Oleg Efremov, a stage production was in the works at the Moscow Art Theater.

Then followed a change of fortune. In a Pravda article dated 13 April 1970, then deputy chief of the Propaganda Section of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, A. Dmitryuk, zeroed in on Ginzburg in a defamatory passage: “In the very least, one cannot say of Otherworldly Encounters that it helps denounce the social and class nature of fascism. But it does reek of sick sensationalism.” Historians cite the party’s official verdict on Ginzburg’s book as one of the factors leading to the retirement of Alexander Tvardovsky as editor in chief of Novyi mir.

Ginzburg’s son, the Berlin-based journalist Yuri Ginzburg, believes that his father was attacked because in his book one could glean “parallels between Hitler’s totalitarian state and Stalin’s state, the traditions of which had remained sacrosanct at home.” It is more likely that Ginzburg was targeted in connection with the changing historical and political context of the Jewish question in the USSR during the late 1960s and early 1970s. After revoking diplomatic relations with Israel in 1967, following the Six-Day War, the USSR pursued an openly belligerent anti-Israel course. A prominent official Jew, Ginzburg was likely targeted to send a message: Only strictly Soviet versions of World War II and Nazism would be tolerated. This message directly applied to the questions about the destruction of European Jewry that Ginzburg posed, however cautiously, to the former Nazis he had interviewed. In a sense, an attack on Ginzburg’s Otherworldly Encounters was part of the Soviet regime’s efforts, renewed in the late 1960s following the end of Krushshev’s Thaw, to obfuscate the memory of the Shoah.

Ginzburg’s book about the personal responsibility of Nazi leaders was withdrawn from publication, the stage version from production, and Ginzburg was blacklisted for a few years as a writer of prose although he continued publishing as a literary translator. (I was unable to gain access to Ginzburg’s archive, held in private hands in Germany, and I don’t know whether he continued to write nonfiction for the desk drawer in the early 1970s.) Otherworldly Encounters did not appear in book form until 1990, the penultimate Soviet year.

On Dec. 10, 1980, after nearly a decade of delays and legal choreography, a Munich court sentenced Kurt Christmann, former commander of SS-Sonderkommando 10A, to 10 years of imprisonment. Ginzburg, who had passed away on 17 September 1980 in Moscow, had not lived to see how his books had brought Nazi criminals to task. He died just five months after completing a draft of his greatest literary achievement, Only my heart was broken…: A Novel-Essay, posthumously published in Novyi mir magazine in August 1981 and issued as a separate book in 1983. Simultaneously an autobiographical novel and a meditation on a Soviet Jew’s inability to unlove Germany even after the Shoah, Ginzburg’s Only my heart was broken… constitutes a unique text of Soviet Shoah memory and as such deserves a broad audience in translation.

Ten years separated the publication and banishment of Otherworldly Encounters and the publication of Only my heart was broken ….” In those years a great deal had changed in the position of Jews in the Soviet Union. In the 1970s over 225,000 Jews left the USSR. While 1978-1979 were the peak years, with over 80,000 Soviet Jews and their families leaving the country, the USSR still claimed about 1.8 million Jews—the world’s third-largest Jewish community after the United States and Israel. Both the creation and the official publication of Ginzburg’s last testament owes itself to the peak years of the Jewish exodus from the USSR.

We are only now starting to understand the function of the major texts of Shoah memory created by official Soviet Jews and published in the USSR, most notably Anatoly Rybakov’s novel Heavy Sand (1979). Books such as Rybakov’s Heavy Sand and Ginzburg’s Only my heart was broken… became an antidote to the massive Jewish emigration. In attempting to offer meaningful if palliative accounts of the Shoah in the occupied Soviet territories, these books pushed the lid off the official Soviet taboo while temporarily soothing some of the restless Soviet Jews who might have been teetering on the verge of emigration.

Ginzburg’s loaded title, Only my heart was broken…, is a translation of Nur mein Herze brach—the second half of the last line of Heine’s poem “Enfant Perdu” (Lost Child). “Enfant Perdu” is the final, 20th part of the cycle “Lazarus”; in Heine’s volume Romanzero: Gedichte, published in Hamburg in 1851, it appears within part II of the volume, “Lamentation,” and right before part III, “Hebrew Melodies.” The term enfant perdu likely goes back to the French Revolution and may refer to a sentry posted at the vanguard of the troops. Broadly speaking, Heine’s poem is about poetry and politics, but allegorically about the plight of being both a Jew and a German poet. The speaker in the poem is a soldier, presumably having fought in the Thirty-Year War, but also a poet whistling “impudent rhymes of a mockery.” This is a literal translation of the final stanza of Heine’s poem “The outpost is abandoned!—The wounds gape—/[While] one falls, the others follow [in his stead];/ I fall still undefeated, and my weapons/Are not broken—only my heart is broken.”

In Chapter 4 of Only my heart was broken…, Ginzburg explained his affinity for Heine and this poem: “What, then, makes people of our time feel close to Heinrich Heine? I believe, it’s his sharpness, his ruthlessness of thought, his ridicule of pompous, talentless villains and their protracted, sickening omnipotence. It was dangerous to fight them: One had to pay with blood, with life. Heine’s obsessive image, ‘Enfant perdu,’—a fighter who ends up perishing without dropping his weapon: ‘Nur mein Herze brach….’ They say: I perish, but I don’t surrender! Heine shifts the logical accent: I don’t surrender, but I perish! Hence the particular tragic quality of his bitter irony.”

The first Jew to become a German national poet, Heine converted to Protestantism to skirt restrictions but never came to terms with his apostasy. He has been popular with Russian poets and translators, and the first known translation of this poem, by the political exile Mikhail Mikhailov, dates to 1864. Perhaps the best-known, albeit still imperfect version, belongs to Ginzburg’s contemporary and competitor Vilgelm Levik, another celebrated Jewish-Russian translator. Jewish authors have identified with Heine in different ways, depending on their own degree of acculturation or Christianization. Anti-Semites of many colors and stripes, the Nazi ideological apparatus especially, targeted Heine as an example of a Jew who allegedly penetrated Aryan culture to corrupt it from within.

For his last book, Ginzburg had initially contemplated the title Confession of a Poetry Translator. According to Irina Ginzburg-Zhurbin, her father had changed the title just a few hours prior to the surgery, after which he never regained consciousness: “Papa [came to] and said to the nurse what the book should be called, citing in German a line from his beloved Heinrich Heine, the hidden Jewish irony of which he had never been able to capture fully in translation: “nur mein Herze brach [razbilos’ lish’ serdtse moe].” The book’s deathbed title evokes profound historical and cultural associations. The last line of Heine’s “Enfant Perdu” captures the quintessence of Ginzburg’s Jewish-Soviet lamentations.

Ginzburg interspersed pages about the investigation of Nazi crimes with reflections on the German poetry he had so lovingly translated, especially his translations of the poetry of the Thirty-Year War and of Schiller. Among the most powerful episodes in the book are Ginzburg’s reflections on the genocide of European Roma and on the fate of Franciska Gaal, the once famous Jewish-Hungarian performer and movie star. The subtitle “novel-essay” underscores the hybrid genre of Ginzburg’s book, where the personal blends with the historical and the literary with the political. This novel sprouts out of the ashes and memories of the victims of Nazism, the way Soviet history itself composes the Jewish author’s biography—often against his or her own will.

“Wheel of Fortune,” the fourth of the book’s six chapters, features Ginzburg’s vintage narrative strategies, conjoining reportage, autobiographical digressions and authorial reflections. Ginzburg recalls a road trip to Latvia he took in the summer of 1966 with his family. Through the character of Simon Mindlin, a master denture technician who had survived but lost his whole family in the Shoah, Ginzburg tells the story of the annihilation of the Jewish community of Libava (Latvian name Liepāja; German name Libau). Ginzburg does not openly identify the town where his mother’s family came from and where Mindlin was living at the time the episode took place, but he undoubtedly refers to Liepāja, Latvia’s third largest city, located over 200 kilometers west of Riga on the west coast of Latvia.

The mass murder of Jews in Libava is particularly well documented in part due to the survival of a cache of photographs, some of them very graphic, taken and preserved by SS-Oberscharführer Karl-Emil Strott. (Prior to Only my heart was broken…, Ginzburg had alluded to these photographs in Otherworldly Encounters.) In his testimony embedded within Ginzburg’s story, the survivor Mindlin refers to Peski (literary “sands” in Russian; ”Šķēde” in Latvian), an area of dunes on the Baltic coast north of Liepāja, where on Dec. 14–17, 1941, over 2,700 local Jews were murdered by Nazi mobile killing squads and Latvian collaborators, including members of the Aizsargi (“Land Guard”). Over 7,000 Jews lived in Libava prior to the Nazi invasion of the USSR; about 200 survived the Nazi occupation.

Ginzburg’s guide Mindlin points to a popular area for seaside summer homes located right next to the killing site. As he puts is, at Peski one literally stands on the bones. At the very end of the episode, Mindlin brings Ginzburg and his family to an old cemetery. For the construction of Soviet Shoah memory, the following passage is particularly significant (translation mine):

The cemetery through which we were walking was very old, with many abandoned and overgrown graves: sections of ancient gravestones with rubbed-off lettering had taken root and sunk into the earth, resembling stakes. Apparently under one such gravestone lay my great-grandfather, and from direct contact with this earth I felt as though an electrical shock was going through me: for the first time in my life I really, physically felt the linkage of generations, that greatest mystery of being, binding my ancestors with me, and me—through my children—with my unknown successors. …

Having guessed what I was feeling, Mindlin began to speak, drawing on numerous details, like an experienced tour guide, about the history of the local families, in turn addressing me and my children. And they stood there, tired of the excursion, of Mindlin’s stories. Languid from having been in the sun that was getting hotter and hotter, they pulled me by the sleeve, quietly urging, ‘Let’s go to the beach …’

The writer’s children—here betokening the assimilated children of Soviet Jews in the 1960s and ’70s—are not moved. They want to leave this site of suppressed Jewish memory and return to reading their books (the son—Heavy Flows the Don, the daughter—A Farewell to Arms) and having fun. Ginzburg’s own Jewish heart keeps breaking as he stands with his oblivious Soviet children—a short distance from the site of Nazi atrocities and near his ancestral graves in a Sovietized Latvia.

In post-Soviet Russia, Lev Ginzburg is remembered as a translator yet forgotten as an anti-Fascist polemicist and a talented prose writer. In honoring Ginzburg’s contributions, we acknowledge the many contradictions of Jewish-Soviet intelligentsia—the very contradictions his life and legacy embodied so fully, and the contradictions that Israel, the United States, Canada, and Germany have inherited over the past 40 years without knowing how to absorb, translate, or assimilate them.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual author and a professor at Boston College. He was born in Moscow and emigrated in 1987. His recent books include A Russian Immigrant: Three Novellas and Immigrant Baggage, a memoir. Shrayer’s new collection of poetry, Kinship, will be published in April 2024.