Sweating the Small Stuff

In Tractate Bava Kama, the Talmud teaches us how to be religious by minding life’s most mundane details

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

I began studying Talmud in fifth grade. We began with the sixth chapter of Bava Kama, the tractate that includes tort law and the laws of damages. Beginning Talmud is exciting; I was awaiting discussions of God, or perhaps the mystical ideas of Jewish practice, or, at the very least, I had hoped for more depth to the Jewish concepts I was already familiar with, such as the laws of Shabbos and blessings. Instead, most of my fifth grade introduction to Talmud was about cows.

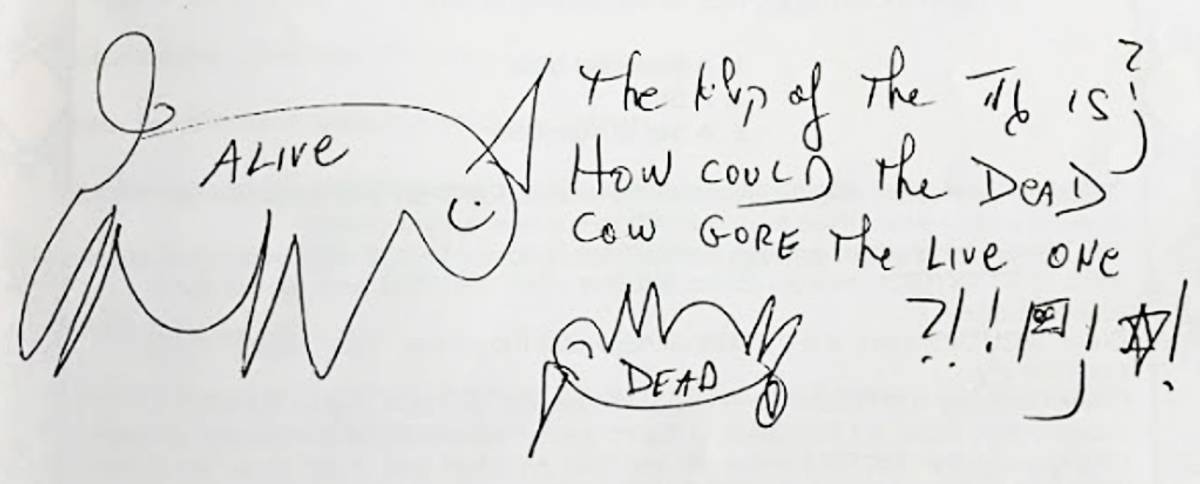

What happens if a cow gores another cow? What happens if someone’s cow causes damage to someone’s property? As a boy who lived on Long Island, I was woefully unprepared for this much cow talk. Every page of Talmud felt like a panel from Gary Larson’s Far Side comics. My rebbe in eighth grade, Rabbi Pressman, would draw crude comic illustrations of cows on the whiteboard. He wasn’t much of an artist, but we appreciated his attempt to make the Talmud feel more relevant. As memorable as Rabbi Pressman’s cows may have been, I was still left somewhat disappointed from my early introduction to Talmud study. Where was God, Shabbos, divinity? Is the secret of Jewish spirituality somehow just about cows? A closer look at Bava Kama, however, reveals that the majesty and divinity of Talmud may just be hiding in plain sight—within the everyday concerns of torts, damages, and yes, even cows.

I am not the first to experience disappointment with the Talmudic preoccupation with cows. In the Oct. 31, 1940, issue of HaKriya V’Hakedusha, the Torah journal of Chabad hasidut, a Yiddish article titled “Toras Chassidus Chabad” was published, purportedly presenting the Hasidic approach to Talmud study. Based on the Mishnah in Bava Kama that opens with the phrase “shor sh’nagach es haparah,” when an ox gores a cow, the author wonders why such mundane theoretical questions occupy so much time in the beit midrash, or house of study. “Important as it may be,” the author writes, “it is totally mundane.” What spirituality are such passages in Talmud meant to convey? “The superficial study of this Mishnah has no connection with the Deity, and reminds its students very little of God,” the author, under the pseudonym A.Y. Segel, writes. Instead, the article suggests, such Talmudic discussion requires Hasidic interpretation in order to uncover the mystical divinity latent beneath such passages.

Courtesy the author

The article caused a furor among adherents to more classical Talmud study. Subsequent issues of the Chabad journal featured letters to the editor that felt the article was bordering on heresy for questioning the spiritual value of cow-based Talmudic conversations. As Rabbi Nathan Kaminetsky discusses at length in his magisterial work Making of a Godol, leaders in the yeshiva world felt it was necessary to pen a rebuttal that would reassert the importance of seemingly mundane conversations common in the yeshiva curriculum. As Kaminetsky reports, a responding article was published under the name Y.D. Zamir, supposedly a pseudonym for the great Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, whose last name means “songbird” in Russian (zamir is songbird in Hebrew). Koren Publishers, in a nod to the meaning of the Soloveitchik name, actually include a picture of a songbird on the back cover of many of Rabbi Soloveitchik’s books. Despite the efforts of many family members and scholars, most notably my dearest friend Jake Sasson, Rabbi Soloveitchik’s response has never been found. Some even question whether it exists.

What makes the Talmud’s laws of damages any different from tort law in any other legal system? Bava Kama is not only a new tractate, it begins a new order of the Mishnah known as Seder Nezikin, the Order of Damages. This section is qualitatively different from the five other orders of Mishnah. The laws of Shabbos or the laws of sacrifices do not have any clear parallels in secular law—these Talmudic discussions invite you into a new world. Not so for the world of Nezikin. Damages are a familiar concept to anyone—Jewish or non-Jewish. Fender benders, borrowing something and losing it, “accidentally” eating food in the company fridge that doesn’t belong to you—these are the mundane issues explored in Seder Nezikin. We know this world. Even if cows may be foreign to this Long Island boy, this tractate is still bewildering—not because it is so unusual but precisely the opposite: because these are the obligations I am familiar with from just being a law-abiding citizen. So where is the spiritual magic within the world of Seder Nezikin?

In most societies, the laws of damages are designed to reinforce societal equilibrium and reciprocity. If you slam into someone else’s car, you need to pay for that damage. Without a legal system enforcing the laws of damages, society would descend into chaos. The pragmatic reciprocity enforced through secular legal systems ensures that society can function.

Jewish law adds an additional component, infusing societal pragmatism with religious idealism. Normally we associate religious obligations with solemn prayer, devout study, and joyous holidays. Nezikin flips the script. As Rabbi Michael Rosensweig explains, this entire part of the Talmud stands at the nexus where pragmatism and idealism meet. Through Seder Nezikin we can find divinity in perhaps the most important place of all: within each other. We don’t just refrain from causing each other damage because we have a practical need for law and order to prevail. We do it because we strive for a higher order of being.

The 12th-century scholar Rabbi Meir Abulafia explained this well in his commentary Yad Ramah. The entire prohibition of causing damages, he suggested, is an outgrowth of the biblical commandment to love your neighbor as yourself. Seder Nezikin may not feel otherworldly, but it requires us, acting as emissaries of God, to transform and infuse our mundane world with religious idealism. As Rabbeinu Yonah explains in his commentary on the first Mishnah in Pirkei Avos, the laws of damages contain the ingredients necessary to bake divinity within the very fabric of our mundane world.

The Talmud itself seems to confirm this worldview, doubling down on the holiness of being very careful not to cause pain and discomfort to your fellow human beings. If you want to become a Hasid, the Talmud writes, learn the laws of damages. You don’t need to move to Williamsburg, you don’t need to wear a shtreimel, you don’t even need to speak Yiddish. A Hasid, the Talmud reminds us, is someone who can find divinity not just everywhere but within everyone.

Seder Nezikin is the reminder that if Talmud study only transforms the otherworldly parts of religious life—Shabbos, prayer, and the like—but leaves your interpersonal obligations the same as when you arrived then you haven’t really immersed yourself in the world of the Talmud. Real commitment to religious life means the mundane interactions of our everyday life—shopping carts slamming into cars, cutting people in line, road rage—need to be transformed as well. If religious growth does not also translate into everyday decency and care for others, one should rightly wonder if there has even been any religious growth at all. Seder Nezikin gives us a new pair of glasses where we can look at the proverbial cows of this world with the same wonder that we gaze at Shabbos candles. It is the ultimate reminder that the most important religious illumination is that which emerges from our friends and neighbors. “Earth’s crammed with heaven,” writes Elizabeth Barrett Browning. “And every common bush afire with God.”

Seder Nezikin gives us the lens to see such a world where religious ideals extend beyond the synagogue and beit midrash. Within the world of Seder Nezikin, cows can be holy, our interpersonal relationships become religiously ambitious, and every common bush afire with God.

הדרן עלך מסכת בבא קמא והדרך עלן

Dovid Bashevkin is the Director of Education at NCSY and author of Sin·a·gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought. He is the founder of 18Forty, a media site exploring big Jewish questions. His Twitter feed is @DBashIdeas.