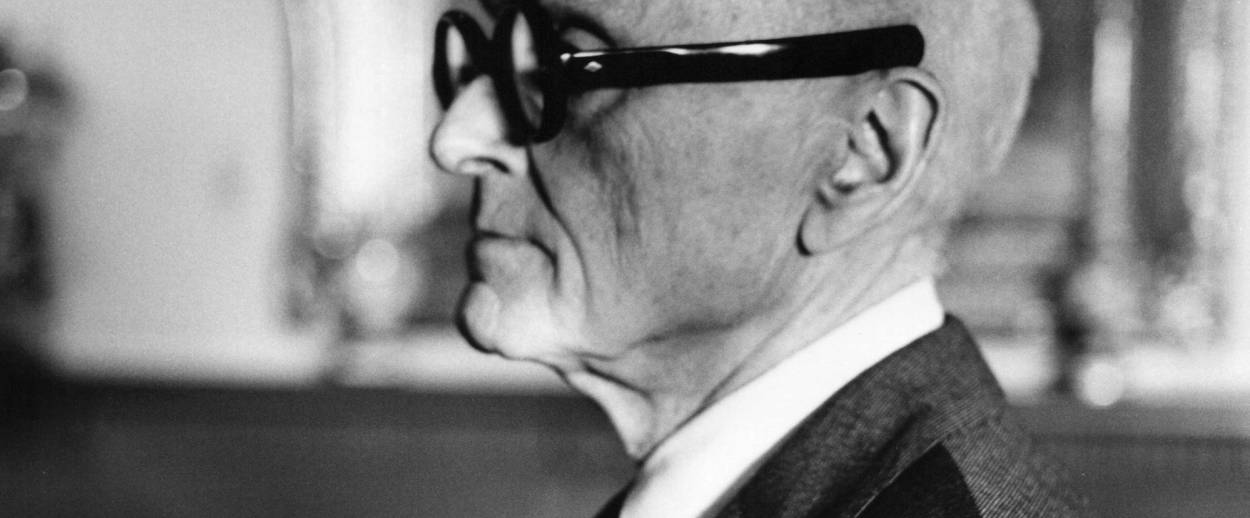

Just how much of a Nazi was the most important American architect of the 20th century? Per Mark Lamster’s new The Man in the Glass House: Philip Johnson, Architect of the Modern Century, the answer is nothing short of astonishing, albeit only in the negative sense of the word.

Lamster, the architectural critic for the Dallas Morning News, exhumes every atrocious detail of Johnson’s seven-plus years as a professional fascist. The book is worth reading for anyone interested in architecture, or for that matter in the eternally fraught relationship between aesthetics and morality. It turns out that on the scale of pro-fascist enthusiasm that spans from youthful dalliance to full-blown Charles Lindbergh-type true belief, Johnson, the creator of modernism and postmodernism and someone whose aesthetic philosophy came to define much of the built landscape in which we are all now stuck, belongs decidedly on the Lindbergh end.

Here’s an incomplete rundown: In 1934, the 28-year-old Johnson and one of his assistants left their posts as architectural curators at the Museum of Modern Art to begin a brownshirts-style discussion group and activist organization in Johnson’s Manhattan townhouse. Johnson had been enthralled by a Hitler Youth rally he attended in Potsdam in 1933 and wrote an article that same year lauding the Third Reich’s architecture; later he would witness two of the notorious annual Nuremberg rallies, in 1937 and 1938. Johnson had a brief stint as a hanger-on in Huey Long’s entourage before becoming an adviser to Father Coughlin in the mid-1930s—the future architect designed the speaking platform, a menacingly stark white wall with disturbing similarities to his later building designs, that the pro-fascist demagogue used during a September 1936 address in Chicago that drew 80,000 spectators. Johnson consorted with German officials in Washington and New York, and several of his other pro-Nazi American friends and contacts were charged with sedition during WWII, a fate Johnson narrowly avoided thanks to family connections and his own high profile as an art scholar and socialite.

Johnson partially bankrolled the publication of a pro-fascist tract self-published by the American diplomat-turned Nazi sympathizer Lawrence Dennis; laundered money from the Nazis provided the rest of the funding, although it’s unclear whether Johnson knew that. Johnson was Dennis’ protégé for a time; other close acquaintances included the pro-Nazi pamphleteer Viola Bodenschatz, the American-born sister-in-law of the Luftwaffe general Karl-Heinrich Bodenschatz, Hermann Goering’s chief of staff. He toured both sides of the front line with Viola Bodenschatz during the German invasion of Poland, and CBS war reporter William Shirer wrote in a diary, published in 1940, that he suspected the future co-designer of Lincoln Center and the Seagram Building was spying on himself and other journalists. Johnson spent the summers of 1937 and ’38 in Germany where he hobnobbed with high-ranking regime officials and held court with the leading lights, such as they were, of the pro-Nazi intelligentsia, including the regime-friendly social theorist Werner Sombart. His last meetings with Nazi officials were in September of 1940, when the regime’s conquest of Europe and extermination of the continent’s Jews were both well underway.

Johnson wasn’t attracted to fascism for narrowly aesthetic or psycho-sexual reasons as he later claimed but because he actually seemed to believe in the idea. “It was easier to whitewash sexual desire than the egregious social and political ideas that truly captivated him,” Lamster writes—after all, Johnson was the kind of Hitler fan who had read Mein Kampf in the original German.

The reasons for his attraction to fascism boil down to a by-now-familiar mix of garden-variety racism, suspicion toward global finance and business, sympathy for an idealized everyman, anxiety over the rise of a new upper class, and raging self-regard: Johnson was an elitist who believed in the quasi-mystical redemptive power of the volk, as well as a megalomaniac who believed he should lead said volk in some form or another. As Lamster writes, his subject was “a man of wealth who was prone to seeing the world in Nietzschean terms.” The author marshals abundant evidence that Johnson was also an anti-Semite, at least for a time: “The Jews bought the paper and are ruining it, naturally,” Johnson fretted of the H.L. Mencken-founded American Mercury in 1936. In his late-’30s writings, Johnson makes it clear that he didn’t consider French Jews to truly be French.

Johnson’s essential shallowness is key to this story. Even in his comparatively better moments, the architect exhibits all the moral sophistication one might expect of a man who thrilled to Adolf Hitler speeches, several of which he witnessed in person. Lamster recalls a meeting between Johnson and the Jewish architect Otto Eisler in Nazi-occupied Brno in 1938—things were “not going well,” explained Eisler, who had recently spent six weeks in Gestapo detention and would go on to survive Auschwitz. Johnson, who had first met Eisler in 1930, exhibited some basic level of concern and asked a Dutch architect friend to help arrange an exit visa. But Johnson didn’t intercede on Eisler’s behalf with any of the several high-ranking Nazi officials he personally knew, and he only broke with fascism in late 1940 when support for the Nazis became personally and professionally untenable. In a particularly lame bit of attempted tshuva, Johnson donated the princely sum of $100 to United Jewish Philanthropies in the fall of 1941; he spent much of the remaining war years as an architectural graduate student at Harvard while trying and failing to get into various intelligence units that would never dream of employing someone who barely avoided a sedition charge. When Johnson was drafted into the military in 1943, the once-celebrated museum curator and co-author of a definitive book on the International Style was sent to clean latrines and serve as glorified cannon fodder during training exercises at various army bases outside of Washington, D.C.

And then, a funny thing happened: The war ended Johnson became kosher, even for Jews. Johnson quickly convinced everyone that he had changed. Robert Finkle, a young Jewish architecture student, began a long stint as Johnson’s protégé and lover in the mid-50s. Johnson designed the Kneses Tifereth Israel synagogue in Port Chester, New York, free of charge in 1956, and although Lamster’s assessment of the building is somewhat harsh—he slags it as an “overblown shoebox” and one of the “opening salvos in what would become the most reviled movement in architectural history,” namely postmodernism—it has much of the stark elegance of the architect’s better-realized projects and its original ark is now in the permanent collection of the Jewish Museum in New York.

Remarkably, Johnson’s first government commission came from the world’s only Jewish state. In 1956, Johnson began designing the Norel Soreq nuclear research facility in Rehovot, which opened in 1960. It is unfortunate that we nonphysicists will probably never get to see the facility in person, because it looks like one of the more mind-bending modern structures in Israel. Lamster rightly calls it a “New Jerusalem,” an austere and kitsch-free vision of the ancient Temple complete with an inner courtyard and a Holy of Holies encasing its research reactor. Few buildings in Israel merge the appeal to divine authority and the dread immediacy of earthly power quite as effectively or as fearsomely. Norel Soreq also conveys Johnson’s genius as well as anything he ever built. His best structures are marvels of harmony and scale, and unlike the work of Johnson’s more pretentious peers they often speak in a language that just about anyone can understand.

Could Johnson have achieved such deep insights about space and power without spending nearly a decade as an actual fascist? The answer is emphatically yes: There are architects who are much more dehumanizing in their style, and even more enchanted with the notion of the themselves as sculptors of society and human nature who nevertheless managed not to attend a single Nazi rally, never mind several of them. Johnson’s Nazi period wasn’t a minor or unfortunate stop-off on the road to genius, or some regrettably essential ingredient in whatever he eventually became. But it’s also hard to ignore the authoritarian characteristics of some of his more celebrated work. Many of Johnson’s greatest structures are both gigantic and strikingly blank, and they work because they hold the Olympian vision of the architect against a viewer’s relative smallness. Johnson’s aesthetic values have a deeply sinister glint to them in light of his personal history; worse still, it’s hard or maybe impossible to disentangle those values from the qualities that make his buildings so distinctive.

At minimum, the whole queasy story betrays an almost unfathomable cynicism that’s key to understanding the man and his work. Writing in the context of the Tifereth Israel commission, Lamster raises the possibility Johnson was “a nihilist with a detached moral compass,” “congenitally insecure,” and “prone to biting the feeding hand and to courting controversy.” A prior belief in fascism isn’t a necessary component for convincing oneself that they can and should shape reality in their own unique image, but a breezily self-focused approach to the big ethical questions certainly helps move things along. A nearly sociopathic ability to tune out every voice but one’s own can lead to Nuremberg or Jerusalem, and in Johnson’s case it led to both.

Johnson’s cynicism was equaled by that of society at large. The architectural powers that be—which include the multilayered political, cultural, and artistic forces that commission, design, build, use, and inevitably judge major building projects—decided that the architect’s crimes weren’t worthy of lifetime banishment from the profession. Had the opposite decision been made and the defensible conclusion reached that repentance for sins of Johnson’s magnitude was simply impossible, the elegantly sloping pediment of the AT&T building (still the greatest Manhattan skyscraper of the last 50 years?), the flying saucers of the New York State Pavilion, the miniature emerald city of PPG Place in Pittsburgh, and the stunning kodesh kodeshin for the nuclear age that sits just south of Tel Aviv would never have been built. Johnson’s career is a tribute to the power or at least the utility of forgiveness—or maybe just of forgetfulness—even when it isn’t wholly deserved. Luckily for us, buildings with creators of dubious character can’t really be memory-holed, and Johnson’s will likely stand for centuries, monuments to the disturbingly faint relationship between personal virtue and creative greatness, as well as to raw ego’s proximity to both genius and evil.

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.