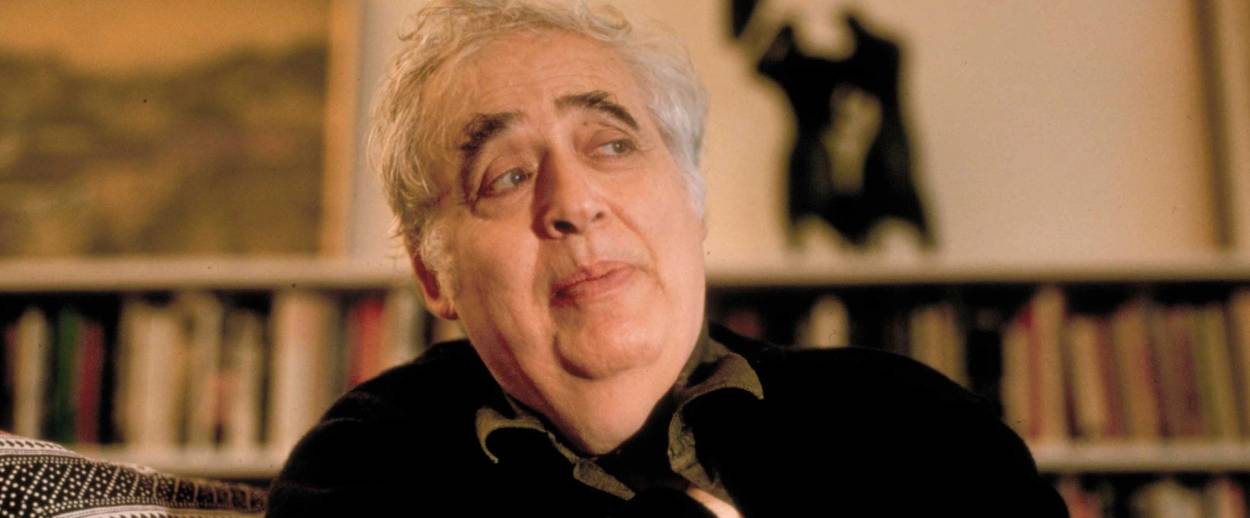

Harold Bloom

The late great literary critic ‘refused to judge books on any other basis than their imaginative strength’

Harold Bloom was bigger than life. When he died earlier this week at the age of 89, he took a universe of wisdom and energy with him. Who will read all the books now, and who will write about them? Though Bloom had been ill for some time, we were all shocked by his death. “I always thought he was immortal,” a friend said to me when it happened.

I first walked into Bloom’s class in the early 1980s at Yale. Many decades later, Harold, always obsessed with chronology, would remind me that I had reached the age he was when I first met him. He taught from scratch the books that had knocked him over: in the class I took it was Ruskin, Pater, Wilde, Nietzsche, and more. In every seminar Bloom transmitted the galvanizing feeling of just now coming to his ideas, and so he was. There was nothing stale, nothing rehearsed. He listened to us, too, though he usually knew what we were saying before we said it.

Harold devoured new books with urgent gusto, going into ecstasies over the good parts and wincing at the bad ones. He was an avid writer of fan letters to poets and novelists whose work he liked, from Anne Carson and Ursula LeGuin to, most recently, the poet Rowan Ricardo Phillips. In recent years he was a great emailer, and his deep friendship with LeGuin was conducted entirely via computer.

At a pinch Harold would read anything, even bad books, and once wrote a review of a Danielle Steele novel for, if I remember correctly, Cosmopolitan. He described the review to me this way: “Two gentlemen are trying to zoombinate the same lady, but when they meet, they get along, the author writes, ‘like a horse on fire.’ My whole review was a cadenza on firey horses.” But Bloom insisted that there is a permanent difference between Danielle Steele, J.K. Rowling, or George R.R. Martin and real literature. The real stuff was what mattered. Cling to what gives you more life, he advised, whether it’s Shakespeare and Dante or 21st-century writers like Joshua Cohen and Jay Wright.

Bloom got tenure at Yale in the late 1950s by the skin of his teeth, in part because his mentor, the Shelley expert Frederick Pottle, shamed the tenure committee by suggesting their opposition was really to Bloom’s Jewishness. His insistence that books give you more life would probably get him denied tenure in today’s conformist academy, which often focuses on ideology rather than exploring what literature actually does for the reader. This is a mistake, since Bloom’s way of telling us why books are worthwhile is a vital necessity if we are to sustain what’s left of our literary culture.

Bloom championed writers of all backgrounds and identities, but he refused to judge books on any other basis than their imaginative strength. That is a test that each reader makes for herself, and Harold was there to testify to his own devotion, nothing else. After reading enough of Bloom you are swayed by his personal canon and then, to some degree, it may become yours as well.

Harold just couldn’t get enough. No one else I ever knew possessed anything like Bloom’s passion for books, his sheer commitment to reading. Diving into a book was life to him, yes, but, and this was the surprising part, being with friends was too. A hungry curiosity about other people is not usually the distinguishing mark of famous academics, but Bloom was the exception. Intensely affectionate, a hugger and head-kisser, he devoted himself to former students like me and to the writers whose work he loved. His gracious wife Jeanne, like Harold, welcomed my wife and son to their home too.

I remember listening to Bud Powell with Harold in the New York apartment where he and Jeanne stayed when they weren’t in New Haven. As a young man Harold haunted the jazz clubs of New York, where he told Powell to read Hart Crane, the literary equivalent of bebop. I have sometimes thought of Harold as a jazz improviser, rebellious and enlightening like Powell or Coltrane. His writing, especially toward the end of his life, became increasingly personal, shadowed by mortality yet at the same time joyous, funny, and heartening. He is a good writer to turn to when you are depressed: try How to Read and Why, Shakespeare, Jesus and Yahweh, The American Religion, or The Book of J, Bloom’s first widely popular book.

“Harold means splitter of skulls in Danish,” he told me once, ruefully. But his Hebrew name was Zvi Hirsch, and over time he came more and more to insist that the Jews were a crucial hidden source for our ideas about authority, poetic creation, and selfhood. To the end of his life he meditated on the rich connection between the Hebrew Bible and Freud.

I remember from years ago a typical phone message from Harold: “Mikidge Pickidge, fortunate swain, I miss you, call me. Much love from old Bloom…I pinch your claws” (this, from S.J. Perelman, was one of his favorite phrases). This time, instead of calling back, I will pick up one of his books. There he is still, on the page, exhorting and wisecracking, head over heels in his reading, infectious as ever.

***

Harold Bloom died at 89 this week.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.