A Man of Principle

Tablet Original Fiction: Sammy Kofer takes a cruise

He carries a heavy gut. When he leaves his cabin and crosses the ship’s central atrium, his enlarged belly appears to be such a burden that he must arch his back and hoist his shoulders to support it. His legs and arms are thin. His hair is white, thick, cropped close on the sides and sprouting upward like a shaving brush. As to shaving, anyone observing him might notice that he often doesn’t; an eccentric distribution of white stubble shows on his cheeks, chin, and throat at almost any hour. He dresses during the day in extra-large soccer shirts, baggy shorts, and moccasins without socks.

He spreads his feet outward when he walks, yet he’s not especially comical looking. His face, though always unsmiling, is not unfriendly. He looks as if he were deep in thought, but there is rarely anything said to confirm this impression. In various of the ship’s lounges, and the Seven Seas showroom, and the Rembrandt dining room, as well as on shore excursions, he is always alone. He seems eager to talk to people and tries hard to make friends, but there is something about him that just puts people off.

Who is he? Almost everyone watches, but no one cares. No one especially cares about anyone aboard beyond the spouses or friends they brought with them on the long cruise to South America and Antarctica, or the table mates with whom they share the evening meal at assigned tables. There is no social glue tying these many hundreds of people together. They are here with one another coincidentally, and regard the haphazard nature of their proximity as at times interesting, at other times an annoyance. They are a bit like a class of incoming freshmen, or the inmates of a closed medical facility, or strangers sharing floor space in an evacuation center.

As a result of his lack of social acceptance in the first week of the voyage, Sammy Kofer rarely visits the public rooms during the day. If land is in view, or there is anything at all to see other than unbroken ocean—perhaps an occasional passing ship or pod of dolphins—he will come out on deck to take pictures. And often he’ll linger outside on a deck chair, reading a book from the ship’s library, then closing his eyes for a doze. The rest of the time it could be assumed, if anyone were bothering to assume anything, he spends inside his cabin. His presence may attract attention, but there is no one to notice his absence.

***

On the first of the 66 nights of the journey, as the ship headed away from Fort Lauderdale toward its first port of call, Sammy had presented himself at the dining room’s central desk along with everyone else and was escorted, like everyone else, to the table to which he had been permanently assigned. On that occasion he exhibited enough social awareness to have replaced his soccer shirt with something with a collar, but this was a white polo shirt and not at all the sort of thing men customarily put on for dinner on high-end cruises. With the polo shirt, he wore gray trousers and a jacket that came from a somewhat darker, and to all appearances older, gray suit. It’s not that he was oblivious to his own appearance, only that he believed himself to be superior to such superficial requirements.

He sat down in the chair that the waiter pulled out for him at the six-person table, hoping that some of his table mates might be single travelers like himself. He looked eagerly at the man and woman to his right, and then turned toward the empty chair on his left and the woman and man sitting on its other side. “Good evening,” he said in heavily accented English, and thrust out his hand to the nearest woman. “I’m Sammy Kofer, and I come from Imperial Valley, California.” He didn’t bother to explain that his pronunciation came from Ukraine by way of Israel.

Contrary to his hopes, the table turned out to be made up entirely of the two couples and himself. The sixth person, a stranger to them all, never showed up. Worse still, those present were interrelated. The woman to whom he had introduced himself, a squarish personage with precision-cut short dark hair, shook his hand with a firm grip and told him that her name was Peg. “My husband Chuck and I live in Florida,” she said in a flat, no-nonsense tone. “These two are my brother Walter and his wife, who reside in Virginia. Walter is a retired army colonel. We grew up in Upper Michigan.”

Brother and sister resembled Easter Island moai, so square and chiseled and identical were they. Their spouses seemed more ordinary, and subsidiary to the two of them, and Sammy had no doubt that this was not going to be the best table for him.

When he returned to the dining room on the next night—the ship was then nosing its way south-southeast between Cuba and Haiti—he asked that the dining room staff put him at a different table. Such changes were complicated, but the manager obliged. They found a place for him in the smaller, auxiliary dining room. Here he was seated with a dyspeptic-looking Belgian and his stylish Chinese American girlfriend, along with a Portuguese man with his African American wife and their daughter. The Belgian spoke fragmentary English in a mutter, the Portuguese had almost no English at all, and neither the gorgeous Chinese girl nor the African American seemed inclined to say much beyond “butter, please,” or “I’ll try the shrimp.”

Only the teenaged daughter said anything to him at all. “Where?” she asked, when Sammy told them he was from Imperial Valley, California. Taking the question as showing interest rather than what it was—an adolescent’s dismissive comment—he hastened to give a short geological history of the valley. There was no further comment from anyone. They were neither talkers nor interested in the natural world. He decided to move on.

Another night, another table. He switched to the second of the two seatings, the one from 8 to 10 o’clock, hoping for better luck. At one table, which was full of lively conversation when he got there, he had the mistaken impression that he was getting along well enough to bring up the subject dearest to his heart: that rules and regulations, as well as various religious prohibitions, work against the natural, healthy human state.

“You take all these allergies and mental illnesses, smoking pot and the like. Once the human body is allowed to return to its natural way of life, these ailments disappear by themselves. Nature takes care of us. We don’t need society or the medical profession or God to tell us what to do and not do.”

But one dominant male at the table turned out to be a retired physician and another had been a military chaplain in Vietnam. Later, the physician’s wife discreetly asked the manager to place Mr. Kofer elsewhere, as he was argumentative and not at all good for her hypertension.

Sammy thus became what the waiters referred to as a floater, a passenger assigned to a different table almost every night. The musical chairs game did not go well for his desire—a hope that continued to run, perversely, across the current of many years of actual experience—to find not only agreeable companions, but female ones in particular.

Whenever he dined at a table with a reasonably attractive single woman, that hour in her company led him to conclude that she was either utterly humorless (he had encountered two such grim ladies aboard), a committed spinster (to be avoided), or a person from a segment of society he could never expect to be part of even if he approved of it—which, with his ideals, he certainly did not. There was no point in their being cultured and charming and shutting him out with their table manners, their knowing which of two forks to pick up first and which spoon was intended for use with what, for it had long been a matter of principle to him to disdain all such symbols of the caste system. And Sammy Kofer was nothing if not a man of principle.

He knew from experience that his particular principles frequently counted against him with the fairer gender, but it was a surprise to find that he wasn’t able to get anywhere with the men on board, either. He had always appreciated the friendship of his own gender, and would have enjoyed having some conversation with a serious thinker like himself, someone with a skeptical viewpoint and a liberal bent, someone with a dislike for organized diversions of the type so enthusiastically promoted by the ship’s activity director. On his visits to the library to pick out or return a book, or to a lecture in the showroom about an upcoming port of call, he would find almost any excuse to address men who seemed moderately interesting, either on the basis of the sort of book they were reading or the kinds of questions he overheard them asking a speaker or the librarian. But there was never any continuation of conversation after the overture and a mere minute or two of backs and forths.

He felt himself to be, as his own sorry joke termed it, a gefilte fish out of water.

Of the few unattached women he met, one showed signs of having looked striking at one time; a showgirl, perhaps. However, she towered over him in height, responded to the question he asked her about her previous travels in a deep, testosterone-drenched voice, and, he concluded reluctantly after giving it some thought, might conceivably have undergone some gender alteration. Even so, if she had been a head shorter he might have offered to spend time getting to know her. She seemed exceptionally intelligent for a female, only she made him think of his ex-wife. Monette had also been taller than he.

He did not take much notice of the several women he encountered who were on the cruise to get over the deaths of their husbands. Widowhood reminded him too much of his own state, permanently missing lost attachments, his present isolation stretching ahead of him to infinity. He had made a poor adjustment to this fate, and still struggled with it; he didn’t care to face it in someone else. Louise Silver, a nice looking widow from Palm Springs, was one of these. But she had made it clear that she wanted nothing to do with him anyway. From the first, she couldn’t even be bothered to look him in the eye.

It wasn’t until the ship was on its way down the coast of Brazil, after spending six days in the Caribbean and another 10 sailing along the muddy Amazon, that at last some resolution was found for the musical tables routine. He was given a chair one night at a table consisting of two elderly, unattached men who, though hindered by various weaknesses or disabilities, had some substance between their ears and with whom he could feel at home. It was a table adjacent to the one where he had first met Louise, the Palm Springs widow.

ammy Kofer weighed more heavily on Louise, if that was possible, than he did on himself. On his frame rested his enlarged abdomen and his mysterious social burden, but she bore the weight of history—his particular history—almost as cruelly as if it were her own. She had ventured on this trip to relieve herself of the burdens of new widowhood and cancer surgery, not to incur additional troubles.

At the time of the cruise, Louise Silver was in her early 60s, a nicely kept woman of a type found more in New England, where she had spent her childhood, than in the part of the world where she now lived. She had a large, well-shaped head, and kept her thick gray-blond hair cut at jaw length and pinned away from her face with a pair of discreetly understated but not inexpensive pewter barrettes. She favored neatly pressed cotton blouses and modest skirts, and on her feet she wore sensible, low-heeled shoes or open sandals.

Louise’s family had emigrated to America in the mid-1800s and done well. Her liberal arts education, at one of the Seven Sisters colleges, had been expensive and first rate. A bit reserved and introspective, she nevertheless made a consistently pleasant social companion, able to discuss almost any subject that came up in a general, polite kind of way, or to express interest and occasional insights on topics that were new to her. Her move west, to Palm Springs, California, had taken place some 25 years before, when her new husband took up a rabbinical post there. Trained as a psychologist, and childless, she established a private practice in marriage and family counseling, serving the Imperial and Coachella valleys.

When Sammy Kofer first turned up at her table, Louise did not know him on sight. She smiled politely across at him when the waiter showed him to the only empty chair, somewhat late, interrupting a conversation among people who, over the course of five evenings, had become easy and relaxed with one another. As he gazed into each face in turn with an unsmiling but eager expression, she observed a certain look in his eyes that said to her, “You may not like me but here I am anyway. I challenge you to rise high enough to be my friend.” Louise, who could read people well, saw that about him. Even before her clinical training, she had had that knack. And since she had encountered such challenges in the faces of others before him and been easily able to rise high enough, she returned the look with an acknowledging eyebrow ever-so-slightly raised, before turning to give the waiting attendant her order. And heard—just as she was finished saying, “I’ll have the escargot, please Gede,”—the accented and gusty voice of the newcomer announcing, “My name is Sammy Kofer and I come from the Imperial Valley, California.”

Unnamed chemicals coursed through her body’s core, causing various arteries and organs, as well as her throat, to constrict. She and Sammy Kofer had seen one another only once, on the other side of a courtroom, during a hearing (pursuant to his divorce) regarding his suitability for the right to spend unsupervised time with his two young children, Aviva and Alan. That was years ago, perhaps as many as 12. The man had been denied that right, largely because of her professional testimony.

Her waiter stood patiently beside her chair in expectation of receiving the rest of her dinner order. Louise looked up into that young man’s soulful eyes as if he could help her, and at the same time reached inward to find the polished front that many introverts and all actors learn to erect to ward off terrors and fear-related mishaps. Outwardly betrayed not one bit by the shock that nonetheless echoed through her, she drew a breath to relax her vocal cords and gave Gede the rest of a coherent order, although not the choices she had originally intended, for those had entirely dropped from her mind. She no longer cared what she ate, or if she ate at all.

Then Gede moved to the next person, and she again turned toward Sammy Kofer and saw that yes, it was the man in the courtroom, older now, and considerably heavier and more gray. “Aviva’s so-called father,” as Monette Kofer had put it during one follow-up session. Louise knew better than most that the so-called father had done much harm to his children, and it would seem from his presence on this ship that he was still failing to take his paternal responsibilities seriously. Twelve years ago, he managed to convince the court that he did not have the means to pay child support, yet here he was, on this luxury cruise. The distaste she felt about that, along with everything else she knew about his case, was going down like poison. But there it was.

At least he did not come to her table again after that night. If he had, she would have sought a different spot for herself. She had undertaken the trip as a symbol of life resumed. How ironic that, having committed herself to moving forward, she should find her course intercepted by so troublesome a person from the past.

***

Most mornings, Louise ate breakfast on her private veranda, often in her pajamas when the ship was not in port. Later, she would either work out at the gym or have her hair and nails done. She took part in a Photoshop workshop three times a week when they were at sea, always made a point of attending lectures pertaining to the next port of call, ate lunch poolside or at the buffet on the stern deck, and chatted with new acquaintances or sat out the afternoon with a book. Under this self-indulgent regime, she had begun to think less often, and less painfully, about her dead husband and her cross-cut abdomen and the future effects of radiation on her organs and cells. Were it not for the presence of Sammy Kofer, this would have been the loveliest of lives.

But Sammy Kofer was aboard, and the gauzy fabric of altered reality that comes with traveling to another world had been torn. Each day following that first shocking encounter, she found herself anxious about running into him. What should she say to him when she did? What could she say?

“Best to ignore him,” her husband would have advised. “Since he doesn’t know who you are, you’re perfectly justified in acting as if you don’t know him.” It was sensible, so she did just that, pretending to be preoccupied or in a hurry to get somewhere on the rare occasions when she saw him approaching. Yet for some mysterious reason, she found it punishing. The silence was punishing. She felt an obscure urge toward disclosure.

One evening, while taking a shower before dinner and not consciously thinking about Sammy Kofer at all, she was suddenly struck with the notion that she was failing at some ethical duty. And yet what could that duty entail? Was she obliged to tell the man that she knew him? There seemed nothing to be gained by it. It might momentarily relieve her mind, but neither of them could benefit from the bond her disclosure would inevitably create between them. He would know that she knew his secret, and she would be left to deal with his anger and hostility. Such a bond would be like a chain circling both their waists and locking them heavily together in the midst of all this lighthearted adventuring and carefree entertainment. No, she would not do it. She had to keep silent and try to make the best of it.

Meanwhile, the ship was bearing its throng of eager passengers to various ports in Brazil. And then one night, after a tour in Recife of sites from which most of the traces of the former Jewish community had been erased, Sammy Kofer turned up again at a table near hers. In fact, he was seated almost directly behind her on the other side of a narrow service counter, the backs of their chairs no more than 5 feet apart. And there he sat each night for many weeks thereafter.

viva Kofer had looked all round-eyed innocence at the first meeting, her pupils so enlarged inside the dark irises that black eyes were practically all there was to see. The child sat very still on one of two carved wooden chairs in Louise’s waiting room, her long legs hanging unnaturally straight and unmoving to just above the floor. Louise had noted this, as well as the way she held her arms straight down with her thumbs tucked inside closed fingers. To Louise, the enormous eyes and the posture indicated undeveloped defense mechanisms and universal readiness; in other words, an uncomprehending child attempting to cope with a disturbing and unpredictable adult world.

As the purpose of the office visit was to determine the girl’s well-being in respect to one parent’s visitation rights—the mother having requested protection for both children from unsupervised visits with their father—Louise asked Aviva’s mother to remain in the waiting room while she led the child into an adjacent playroom. She settled Aviva in a child-size chair where her feet could reach the ground and gave her a pad of drawing paper and a supply of crayons and colored pencils. She then brought her face close to the little girl’s and told her in her most reassuring voice how pleased she would be if Aviva would draw pictures of her house and her family for her. “I’m going to make your pictures into a book, Aviva, and I’ll look at them every day when I know you’ll be coming to see me. That way I can remember everything about you.”

At the mention of the book, the little girl looked at her, the black eyes locking on Louise’s hazel-gray ones. There was a suggestion of tentative trust, along with vast neediness, in that look.

Louise returned to her own office, then, and to the tall mother who, in contrast to her rigid daughter, scarcely held still for a moment as she told her story. Monette had been a dancer in Israel, a graduate of the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance. A cousin of hers, who lived in America, belonged to the statewide agricultural commission that Sammy worked for and, discovering that Sammy was looking for a wife—Jewish women being in short supply in the Imperial Valley—had played matchmaker by phone. The cousin persuaded Sammy to fly to Israel to meet his attractive relative. He assured Monette that Sammy was very, very clever, and told each of them that they were just about the same height.

Not quite; it turned out that she was at least half a head taller, but neither of them was inclined to let a superficial thing like height deter them. Ready meant ready, and both of them understood that it was time to start a family. She said yes when Sammy proposed marriage, then confided to him that with his financial help she would like to open a dance school. She imagined that the school would be in San Diego, the city in which she believed he lived. Sammy agreed.

After the wedding, she and her new husband flew from Israel to San Diego. Then Sammy drove her over the mountains to his house in El Centro, which, in her words, was “a nothing city in the middle of a pathetic desert.” When Monette asked him why he’d claimed to live in San Diego, Sammy in turn asked her if she would have known where El Centro was if he’d told her. True enough; Louise, who lived in a better part of the same desert, knew that even most Californians had never heard of El Centro. But the deception had been particularly unfair to Monette.

“I spent my life in Israel, how could I know they would have no interest in modern dance in El Centro?” she complained. “Did Sammy bother to find out? He knows nothing about dance, he’s completely left-footed. All these people want is salsa and hip-hop besides, of course, ballet for their little girls. But expressive dance? Dance as art? This is not something they relate to. Look at me! I was trained by the best! This lie was a terrible beginning for our marriage, a bad trick for a husband to play.”

“You said there were other things about him, too. What things?”

“His name!” she replied scornfully. “You know the meaning of this word Kofer? Kofer means heretic. Sammy adopted that for his name! What kind of a man would do such a thing? I tell you, nothing about this man is normal. He is a joke. A sick, sick joke.” She waved her hands back and forth across her face, as if to erase both the joker and his joke.

When Louise asked her why she sought the court’s protection for her children, Monette leaned forward and brought her forehead down until it touched her knees. “My husband likes to be naked,” she confessed into the muffling fabric of her leggings. “He believes clothes are unnatural. Native people in every warm climate go naked, he said. Clothing is artificial to make us seem something other than what we are. He wanted us all the time to be nude inside our home.”

She sat up, chewing her lower lip. “At first, before Aviva, OK. I didn’t mind dancing naked, I liked to please him. Sammy was a good audience.” She released her lip and smiled at Louise crookedly.

“You had fun with him at first, then?” Louise prompted.

Monette raked the curly, hennaed hair away from her forehead. “Yeah, sure.”

“Sex was OK?”

“Sure.” She waggled her shoulders. “He was funny and awkward. He made me laugh.”

“When you were pregnant with Aviva, did things change? Did your husband seem angry with you, or jealous of the child you were carrying?”

“No. He wanted children.”

“And the second child? Alan? You both also wanted him?”

“Sure!”

“How did you feel about your husband being naked in front of your children?”

“That’s what got me worried. I asked my mother: Can seeing her father naked hurt my daughter? And she said it’s not a good thing, girls don’t understand what they’re seeing, and it also might be arousing to the man. Monette, she told me, you must protect Aviva from seeing his private parts. So I told Sammy that Aviva was getting too old, that he had to start wearing clothes in the house, even if it was only underpants, because it wasn’t good for a little girl that age to see her father’s naked body. My husband got so angry. He walked away from me and slammed the door. Then he came right away back again, picked up Aviva, and carried her with him into the den. I want to know what he is doing in there, but all he can say through the shut door is stay out. I try to get in, but the door’s locked. Then I was crying, and I go, Give me my daughter, she shouldn’t be in there with you naked; it isn’t right. He opens the door and slams it, then opens it again and slams it just to make a louder noise, to make me go away, and I was crying so hard I couldn’t catch my breath. Aviva was crying, too, inside that room; I could hear her crying.

I really had no thought what to do. I felt afraid for what will happen to me and my children with this crazy man. When I could talk again, I telephoned to my mother in Israel, who said I must be very careful, such a reaction from Sammy could be dangerous. But she told me to take steps to protect my children. What steps? You must find a lawyer, my mother said. A lawyer will tell you what to do. Could I hire a lawyer against my husband in America? I didn’t know. But it was not normal for my little girl to see her father naked, and why did he take her into that room with him when he was like that? Why did he need to show his body to her, I was thinking then. His body should be private, between him and me.”

After the session, Louise examined Aviva’s drawings. The little girl had portrayed her mother as a tall figure, arms thrown upwards, her hair a wild scribble of red and brown crayon. Aviva herself was drawn as a disproportionately large child, almost as tall as her mother, wearing a big smile and a red bow in her hair. Both of the male figures—the little brother and the father—were naked, a darkly outlined projection plainly visible between their legs.

Like Monette, Louise believed that Sammy’s nudity belonged in the private sphere of adult intimacy. From her training, she understood that a female child might be sexualized too early by the exposure, particularly where nudity was not part of the societal norm. Moreover, his taking the girl off into a locked room with him—which he made a habit of doing after that, in effect appropriating her as his companion and shutting his wife out—was highly destabilizing to the family dynamic. Though physical abuse had never been determined, nor was any criminal action initiated against him by the time of the visitation-rights hearing, it was reasonable to conclude that the father’s actions at least held a suggestion of incest.

Certainly Sammy’s behavior, the trouble it caused in his home, and his refusal to change his behavior in response to his wife’s discomfort with it—in addition to the chilling possibility that more went on between them at such times than Aviva was capable of expressing—suggested that, in the case of the impending divorce of Monette and her husband, Sammy Kofer ought not to be allowed to visit with his children without supervision. That is what Louise communicated to the court the day of the hearing, using to support her conclusion the presence of the male genitalia in Aviva’s drawings.

io de Janeiro. With 30 or so other passengers, Louise boarded the crowded Corcovado funicular, inching upward through a forested mountainside neighborhood to stand with a couple of hundred other tourists from all over the world at the foot of a cloud- draped statue of Christ. Back at the base of the mountain, stepping off the tram at the Cosme Velho station, she passed Sammy Kofer, who was on his way up. His eyes fell on her for a moment as he passed, and she swung so quickly away from him that her carryall crashed against a pleasant Puerto Rican woman she knew from the ship. After apologies to the woman, Louise hurried to her bus, where her tour group was driven around the avenues and residential side streets of Copacabana, then across town to board the cable cars that swung them up to Sugar Loaf. By then it was the clearest, hottest, most brilliant part of the day. The view from the peak was flawless.

Sammy, on the same tour in reverse, was taken first to Sugar Loaf, which was then damp and foggy, and afterward to see the divine colossus towering upward into a clear blue sky. He had noticed Louise and her attempt at avoiding him at the station below, but put it down, as he had during earlier contacts with the lady, to the superior airs of the ruling class. Staring sourly up at the immense statue, he deemed it to be exactly as he expected, a ridiculously oversize indicator of the muddle-headedness of his fellow man. But the view was fantastic, so he turned to a stranger standing beside him and asked if he would take a picture of him with his, Sammy’s, camera against the backdrop of the coastline below.

They exchanged a few not unpleasant words before Sammy felt the need to share his opinion of the enormous monument to superstition soaring above them. Instead of agreeing, as Sammy hoped he would, the man gave him a startled look, abruptly handed the camera back, and walked away.

During a lull at her own table that night, Louise overheard the men at the smaller table behind her talking about their tours. One of them asked Sammy what he had thought of the stained glass windows of Rio’s ultra-modern cathedral. “Oh, I didn’t bother getting off the bus,” Sammy replied. “I never step foot inside so-called houses of God. I am nothing if not a man of principle.”

Throughout the remainder of the meal, Louise kept her back as rigid as a wall to protect herself from the ever-disturbing presence of the man of principle.

A cold wind churned up the sea at the Falkland Islands. Since there was no pier large enough for the cruise liner to dock, various announcements came early over the public address system concerning the feasibility, in that day’s stormy conditions, of using the ship’s small launches for ferrying passengers to and from shore. When landing operations were finally OK’d by the captain, Louise was one of the first to venture out. Dressed in a quilted down coat she hadn’t worn since her East Coast days, she spent a vigorous couple of hours tramping along a trail that took her through sheep pastures to a penguin colony at the edge of the sea.

Sammy Kofer showed up at the disembarkation deck in time to hear the announcement that all landing operations had been suspended. He therefore spent the day in his cabin, highly annoyed that he would not get a chance to see penguins, but pleased by the fact that at last they had reached the cold southern latitudes and the ship’s air conditioning system was switched off. In Brazil, the interior of his cabin had been chilly enough to force him to keep on his trousers and shirt. Now he was once more able to strip down to the pleasure of his own skin.

hen he was a boy in Kyiv, two children in Sammy’s street caught polio one summer, and his mother sent her children to the country to keep them safe. Shmuli, as he was called then, went to stay with her father’s brother, who owned a small dairy. Every late morning after the milking and mucking out were done, Uncle Ben and his sons would strip off their dirty clothes, cross the field naked to the river, then plunge into the water. After splashing around together for a few carefree minutes, they would return, naked, to the farm, dry off with towels handed them by his uncle’s wife, and, still unclothed, sit down to their midday meal. Young Shmuli, imitating his elders, did the same.

This was his introduction to a new way of life and to the philosophy known as naturism. Uncle Ben held the notion that all things natural were good, that one’s diet should depend largely on vegetables and fruits, with little meat, and that the unclothed human body promotes social equality. “Naked people are equal people,” he would say.

It was Uncle Ben who had adopted the name Kofer for himself and his family, a word that he defined not as “heretic,” as Monette was later to translate it for Louise, but as “freethinker.” The Kofer farm produced and sold a special milk, known far and wide as Kofer-milk, which he promoted as an aid to natural digestion, guaranteed to soothe colicky babies and restore adult digestive disorders to their proper function.

When Shmuli expressed interest in these ideas, instead of shunning him as some members of their extended family did, Ben explained that the institutions and governments of industrial societies, both communist and capitalist, had been devised by wrong-minded men to diminish people’s naturally noble state. Most of the problems of modern life, he claimed, were the result of denial of the state of nature. Organized religions, including the Hebrew one, distorted divine truths readily observable in nature. He believed that God ought to be worshipped privately and, whenever possible, in the out-of-doors. And nude, because the possibility of genuine communion with the Creator is foreclosed in every case where rituals and practices are prescribed by social custom (that is to say, conventional wisdom) or tradition.

Some years later, after Sammy’s family managed to emigrate to Israel, he found a number of naturist groups there; and on occasion, during his army duty, he and a handful of like-minded companions would get leave to go down to the Dead Sea, where they would search out a spot far from the pilgrims and tourists and bathe naked in the salty body of water, then stretch out beneath the sun as God made them until they were happily pickled in brine.

When he came to America to live, he legally took the Kofer name. Although too excitable a personality ever to be steadfast in his principles like his Uncle Ben, he never ceased proclaiming allegiance to the ideals he had learned from him.

***

Snow was falling when Elephant Island came into view. Flake upon gentle flake drifted down across the horizontal surfaces of the ship until the deck wore a coat of ermine. Naturism having encountered one of its more obvious limits at 61 degrees south latitude, Sammy put on his clothes and rode the elevator up to the 11th floor buffet. The busy dining area held a noticeably altered energy that day. Out on the open dining deck at the stern, people wearing parkas and winter hats were crowded against the rail taking pictures of flat-topped icebergs as long and broad as aircraft carriers. Inside, faces that were customarily turned toward table companions and hot food warmers and plates of poached eggs, bangers and mash, or breakfast muffins, were now focused on the salt-streaked windows, beyond which the austere black massifs of Antarctica towered above dazzling ice fields.

Sammy sat down at an empty table with his breakfast tray. The dietary component of Uncle Ben’s philosophy having been forsaken years before, he chewed his way slowly and methodically through a three-egg bacon-and-cheddar omelet and two slices of sourdough toast, his face turned to the window. On the covered deck a short distance away through the glass, he could see Peter Moller, one of his two elderly dinner companions, dressed in a dark overcoat and a hat with earflaps, rubbing his mittened hands up and down his arms while he talked with some animation in his anemic-looking face to the Palm Springs widow. There was more seriousness than usual in Sammy’s own expression as he watched. He had a simmering sense that he had a grievance about this. If the lady felt so superior to him, even avoiding him the way she had at the tram in Rio and whenever they passed each other on the stairs, why should she treat Moller any differently? Was Moller really so much better than him just because he was a doctor?

As he continued to watch them, a perverse desire to interrupt their exchange came over him. But he was wearing his usual soccer shirt and shorts, and hadn’t bothered to put socks on inside his shoes. It didn’t seem like a good idea to venture outside without winter gear.

When he finished his meal, he took the stairs down the five floors to his cabin (riding the elevator up but walking down gave him the illusion of keeping fit), and put on his cold-weather clothes. And it was a very good thing, too, that he had thought to bring his long johns, wool socks, a moth-eaten wool sweater his grandmother had knit for his father back in Ukraine, plus his parka from REI, a gift to himself for the trip. Even with all that, it was breathtakingly cold outside, and of course Moller and the widow were long gone.

He poked around on various decks, some more sheltered than others, taking pictures, as many people were doing, of the frozen coves and prominences of the Antarctic peninsula. He was on the lower bow deck, with numb hands and stinging face, considering going inside but wishing he could get a picture of himself amidst this remarkable scenery that he would never see again (a picture that would at least prove to him, in his lonely old age, that he had actually been to the South Pole) when the Palm Springs widow came through a door near him with a Nikon camera hanging around her neck.

At that moment his response was completely spontaneous—a simple desire to have a photograph of himself so he could go in and get warm. That need overrode any judgments he may have made about her. So he intercepted her at once, pushed his camera forward, and asked her to take his picture with it.

The lady stepped half a step back. She looked offended. Or else she looked frightened—he wasn’t good at reading faces, so he wasn’t sure how she looked, only he was certain that hers was the most unwelcoming female countenance he had ever seen up close. “You’d better ask someone else.” Her voice was as cold as the region through which they sailed.

His little camera was held midway between them. He felt ready to beg, but was too stung by her response and her forbidding face and narrowed eyes and slightly flared nostrils to say anything. It was utterly humiliating. He hated her. What was it, what kind of prejudice would allow her to make him feel like a fool for approaching her with a perfectly reasonable request yet have a long and apparently agreeable chat about this or that on the stern deck with one of his table mates? Perhaps this woman was one of those rabid anti-Semites, the first he had ever personally encountered in his 20-plus years in America.

It was not easy for Sammy to keep his temper, so he turned away instead. She isn’t worth it, he thought in an inner tone full of spite as he pulled open the heavy door and stepped inside. He returned to his cabin, removed his outer clothing, and sat down. Then he got up and opened the bar, something he would ordinarily never have done, and emptied a minibottle of Scotch into a glass. Then, too warm, he took off all the rest of his clothes and stalked about the narrow room, sipping the golden liquid and muttering aloud to himself about the dybbuk from Palm Springs.

***

Louise was greatly disturbed by her overreaction to Sammy Kofer’s simple request. She could have been gracious about it, taken his picture, even spoken a few casual words with him the way she had with that pale-faced man, the retired nephrologist from Rochester. She had behaved as if she couldn’t bear to be near him, yet she knew that was not precisely how she felt. If only her knowledge of him were not so intimate, so disproportionately personal. Though he still had no idea who she was, she was aware that there was not one of the hundreds of passengers aboard who had a connection to her as personal as he did. It seemed almost as if he were a member of her own family, one whom she had never liked.

Having regarded herself for her entire adult life as rational and ethical, Louise now asked herself if a countertransference might be causing her this difficulty. Had she perhaps identified too closely with Monette and Aviva and been sucked into the drama on their behalf? A woman identifying with a mother and child—it could easily happen. And with it might well come a desire to punish. Even so, she would never have thought she could behave in such a heartless manner. Ignoring the man was one thing, but such a cruel rebuff?

It was shocking to recognize how easily she had stepped beyond the original decision to keep her distance. She was in unfamiliar psychic territory and was now overwhelmed by recriminations and self-doubt.

***

The next morning, Sammy Kofer awoke with a terrible sore throat. By midday, he had developed a running nose and a cough. By late afternoon, his bones and muscles ached. The ship’s doctor told him that a bad cold was going around. He gave him Tylenol and the usual advice about getting rest and drinking plenty of fluids.

But it was not a bad cold; it was a vicious illness, and it lasted one week, then almost two. He remained aboard ship while the passengers who hadn’t gotten sick or had already recovered were walking around the parks and preserves of Tierra del Fuego, then exploring Patagonia, and after that taking long scenic tours of the Chilean lake country.

The ship’s northerly heading soon meant warm weather again, and the air conditioning system was again in use. That resulted in a flow of cold air across his nose and throat as he tried to catch up on sleep between bouts of coughing. In the daytime, he was occasionally visited by such violent coughing that he could not maintain full control of his bladder. He didn’t dare to leave his cabin for meals.

He went to the main desk and insisted they shut off the air conditioning in his room. This they were unable to do. “Why is there no on-off switch?” he asked in a voice he didn’t recognize as his. “No matter where I set the thermostat, only freezing air blows in. It isn’t healthy, to breathe such air. It’s unnatural.”

A young officer offered him a roll of duct tape and a scissors. “Sir, you might tape the vent closed. It’s the only suggestion I can offer, sir. If you prefer, one of us will attach it for you.”

Sammy carried the tape and scissors down to his room. Holding onto the wall for balance, he stood on the top of his bed and stretched black tape across the grill. An hour or so after applying it, pressure popped a section away, blowing cold air up toward the ceiling. The flow of air was no longer aimed at his face, but the temperature was still frigid.

He went from nudist to Eskimo, forced to wear long johns, his grandmother’s sweater, plus the complimentary terry-cloth spa robe to bed. He even wound a muffler around his neck and across his mouth to help him sleep. He sucked all day on cough lozenges, which caused his tongue to go numb, which in turn caused a loss of appetite. He was too sick even to feel lonely in his near-total isolation. Only cold.

By the time the ship docked in Valparaiso, his health had begun to improve, but because of the embarrassing, if infrequent, coughing-and-bladder situation, he didn’t dare book a sightseeing tour. Instead, he left his cabin and found a sheltered spot on the top deck where he could watch the activities of the busy commercial port. At lunchtime, he even sat by the pool in the sun and ate a hamburger and french fries with plenty of ketchup, drinking beer from a sweating brown bottle. He didn’t cough and didn’t embarrass himself. He almost felt like himself again.

And then one day he decided he was ready to resume the shore tours. The ship was due to dock the next morning at the Peruvian port of General San Martin. Before the shore excursions desk could close for the evening, he bought himself a ticket for a tour called “The Natural Wonders of Paracas.”

***

“Paracas Preserve—Bus #1,” read the placard in the front window of the motor coach. Making her way along the disorderly wharf past a cement truck and workers doing repairs, Louise joined the line of her fellow passengers and climbed the steep steps into the vehicle. The front seats were already occupied, mostly by disabled or otherwise frail and elderly people. She greeted the people she knew, nodded at others she merely recognized, and stopped to exchange a word with the Australian couple from her table. Halfway along on the driver’s side she found two unoccupied seats and slid across to the window, where she settled her carryall bag on the floor at her feet.

More passengers were coming in behind her and taking their seats, and along with them came Sammy Kofer, who pulled himself up the last step and started down the aisle, his eyes searching for empty places to sit.

Louise’s pulse lurched. Forgetting her intention to end her rudeness, and again detesting her own cowardice, she looked down to avoid meeting his gaze. She couldn’t bring herself even to raise her head and look up until one of the women she knew from the scrapbook workshop sat down in the seat next to her. They chatted, Louise’s dread perfectly hidden behind her quiet voice and calm demeanor, though she felt the hairs on the back of her neck pointing like magnetized needles in the man’s direction. She wondered how she would behave this time if he spoke to her, and again rebuked herself for her continued failure to find a fair-minded position that would gain her some ease.

The bus began to roll, and the local guide introduced himself over an uncertain loudspeaker. The plateau across which the vehicle sped held not a tree, a shrub, nor a blade of grass, and the earth was the uniform yellow-ocher color of Grey Poupon. “The coastal area of Peru is one of the driest deserts on earth,” the guide explained. “The rain clouds that come from the Pacific drop their moisture on the Andes, never along the coast. No more than 2 millimeters of rain fall here in a year.”

The guide called their attention to the highway along which they traveled. It was paved not with asphalt, as asphalt would only melt in the extreme heat. No, it was paved with salt. Salt remained stable here. Why? Because there was never enough water to wash it away. He laughed at their surprised responses. “Repairs here are cheap. It’s like a cooking recipe—all our road crews need to do is add more salt.”

The vehicle soon left the highway and came to a stop on a plateau overlooking an unearthly looking cove. Gaudy green waves knocked against the base of overhanging, mustard-yellow sea cliffs. The exposed sides of the cliffs resembled the desiccated, disintegrating bones of a prehistoric animal.

The guide led his group toward the base of the cliffs, where he said they would see Peruvian boobies, pelicans, and cormorants. If they were lucky, they might spot sea lions stretched out on the offshore rocks. Louise, who regretted having chosen this tour and wished she had remained aboard the ship and read a book, nevertheless started out with the others, but when she noticed Sammy Kofer hanging back just ahead of her, she turned in the other direction and strolled along the beach among the families of Peruvians, who, in spite of the leaden air, were like any other families enjoying a day at the seashore. Then, disturbed by the heavy atmosphere and the unresolvable issue that continued to afflict her, she returned to the bus.

The driver was still seated at the wheel, dozing with his head against the partition behind him. He opened his eyes, nodded, and went back to sleep. Louise walked to her seat, pulled her bag up from the floor, and reached inside for her bottle of drinking water.

Someone stirred somewhere behind her, and she heard a voice—a high, harsh voice like a seagull. “Why you do this to me, lady, huh?” he said.

“I beg your pardon?” she responded, as if there was any doubt who was speaking to her, or why.

“How come you treat me like a piece of dirt but you are oh so friendly to Moller and all these other people? You think I’m not as good as you?”

Turning partway around, she watched Sammy Kofer stand up from the long back seat—where he must have been lying down, for no one had been visible when she entered—and walk rather unsteadily toward her. He stopped a row back and rested his hand on the fabric-covered top of a seat.

Even as she shrank from him, she knew that she must face the problem this time. It was a matter of her integrity; she had never in her life imagined she might rightfully be accused of treating any human being as a piece of dirt. “Mr. Kofer,” she began, as always sounding calmer and clearer than she felt. Inside, though, she was quivering with misgivings. “Sammy. You may not realize it, but you and I have met before.”

“We did? Where? Where did we meet?”

“In court. I was Monette’s psychiatric adviser at the time of your divorce.”

He took a step back. He then took a step forward and seized hold of the seatback with both hands. She felt the threatening tug of his grip, of his weight, against her chair. She turned her head toward the front, where the driver still reassuringly dozed.

She heard silence, absolute silence. And after that more silence. Not a word came for a very long time, time enough for Louise to reflect, as if this were an extended pause in a therapy session, on the many words that the patient might be trying out and rejecting in that silence, the many self-justifications of an offended ego. Such reflection gave her the illusion of being in control again, even as she knew she did not have the fortitude to withstand the weight of everything that was wrong.

When the man finally spoke, his voice sounded as if it came from deep within the overfed regions of his abdomen. “You were so sure that my little girl would be harmed to see me as I am created by nature?” The syllables shook the dusty air of the bus’s interior. “And then, after you and Monette were done punishing me for the crime of going naked in front of my own children, did you or anyone in your Court of Inquisition think how I would ever win them back? You took away everything that mattered most to me. I’m like a man in a bad dream ever since.”

She felt the force of his body as it dropped into the seat behind her. Those were not the words she was expecting.

She shut her eyes and didn’t open them again until she heard people climbing back into the bus. The engine started up, and outside the front windshield, she saw the guide gesturing to the laggards to hurry up. A woman passed along the aisle, stopped next to Sammy, and informed him irritably that he was in her seat. When he didn’t move, she repeated herself.

“I’m staying right here!” Sammy shouted at her.

“OK, OK, OK!” the woman yelled back, moving toward the rear.

The other passengers filed in and took their places. There were a few more grumbles about displacements, but eventually the bus circled away from the beach and barreled toward the salt-paved highway. The Earth itself seemed to tilt and spin as the recognition of the wrong that had been done finally penetrated Louise’s defenses. She had never considered Sammy Kofer to be her responsibility; she had been asked only to evaluate the little girl.

Back at the wharf, the bus had scarcely come to a halt before she gathered up her things and stood. She rushed out without looking back. It was too late. There was nothing she could do. It had been hopeless from the start.

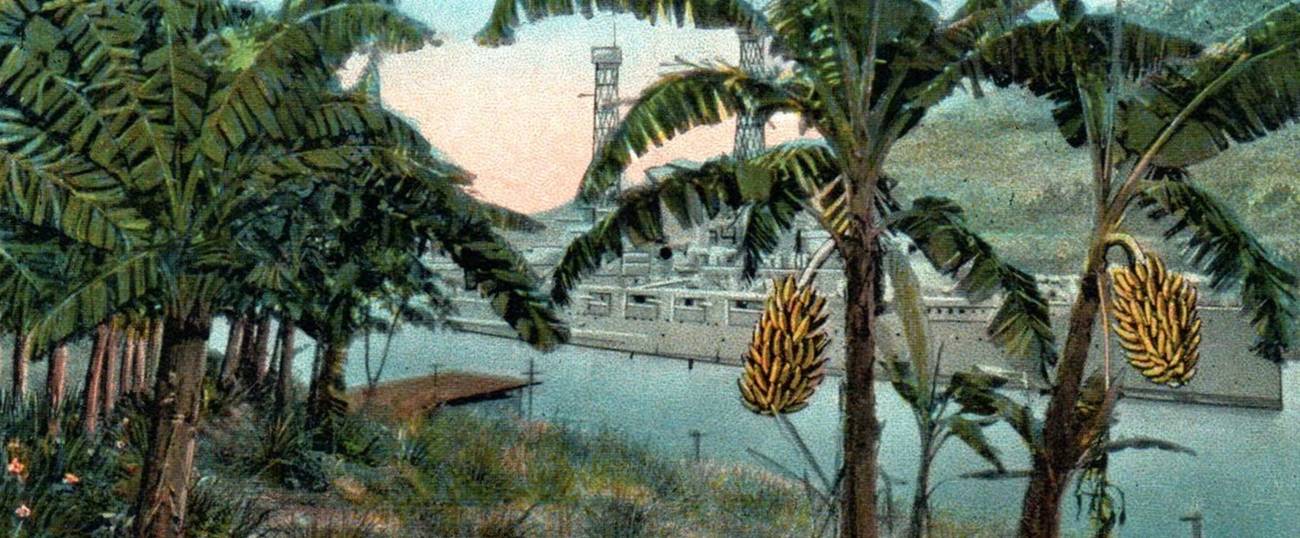

That was the last she saw of him. Because of his illness he had been missing from the dining room for so long that Louise thought nothing of his continued absence at dinner, and was completely unaware that he was no longer aboard. The ship made a two-day stop at Callao, then a final shopping stop in Ecuador. The next major feature of their journey would be the Panama Canal. Beyond that lay Florida, their final destination, where the journey had begun.

At the canal, Louise went out on deck to watch the passage through the final lock. The seawater drained from the enormous chamber and, as their ship slowly lowered, the shore appeared to rise around them. A group of passengers moved away from the rail and headed inside, clearing a view of Peter Moller seated in a chair at the rail observing the waterway. He hadn’t noticed her, and for a moment she considered heading inside after the others, going for a dish of ice cream or the afternoon movie. But she had suffered from her own insufficiency for so many weeks that she approached Mr. Moller instead, and they exchanged a few comments about the afternoon’s passage across the isthmus. Then, in response to the discomfort that still roiled within, she inquired about Mr. Kofer.

“Oh, he left the ship a way back,” Moller, still seated, told her. “He went up to Machu Picchu with his tour, came back briefly, and decided to fly back to California from Lima. I ran into him at the buffet before he went. He told me he didn’t see the point of remaining on the cruise, he had seen what he had come to see. He said he didn’t have a happy time, that he didn’t care for this kind of travel.”

In front of them, the immense doors of the lock stood fully open. The engines started up, and their ship eased into the Atlantic.

“You know, Kofer had rather a fascinating career,” Moller went on, angling his head and squinting at her. “He was an expert on agricultural irrigation in saline conditions. Started out working as a water engineer for the Israelis on some big projects, then took his expertise to California for the farmers’ organization they have out there in the desert. He was a very unusual man. Did you get much of a chance to talk with him?” he asked.

Louise thought of their sole conversation, remembered him inside the empty bus crying out, “Did you think how I could ever win my children back?” She watched as a giant car carrier that had been in the lane beside them began to recede.

“No,” she replied.

***

This is the third of three fictions this week. To read more Tablet Original Fiction, click here.

Emily Adelsohn Corngold, a writer and editor, lives in Pasadena, California.