Roman Holiday

How Jews observe Tisha B’Av in Rome, where the Arch of Titus commemorates the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem

When Titus walked into the Holy Sanctuary of the Temple in Jerusalem with his commanders in 70 C.E., he found it to be far superior to what he had previously heard, wrote Flavius Josephus, a Jewish priest and historian, in his book The Jewish War. Flames were consuming the adjacent rooms, but they had not reached the sanctuary yet. Titus ordered his soldiers to quench the fire, hoping to save the inner part of the Jewish temple. But, Josephus continues in his book, the Roman commander could not restrain the fury of the soldiers; one of them “threw the fire upon the hinges of the gate, in the dark, whereby the flame burst out from within the holy house immediately,” we read in William Whiston’s translation. “And thus was the holy house burnt down.”

After Titus returned to Rome, he was awarded the traditional triumphal ride on a chariot. The spoils from his conquest contributed to the building of the Roman Colosseum. Some of the relics taken from Jerusalem, including the massive, golden menorah, were paraded in the capital.

Josephus wrote his history just a few years later, in Rome. His real name was Yosef ben Matityahu, and he was born in Jerusalem in 37 C.E., but he relocated to the capital of the empire after betraying his own people and accepting the invitation of Titus.

The fascination with what happened to the menorah—more than any other relic taken from the Temple—following its arrival to Rome still lives on here, as it remains a mystery.

“The menorah was placed in Vespasian’s Temple of Peace,” said Samuele Rocca, a historian and senior lecturer at Ariel University. “We know from a text by Procopius that the Vandals took it from Rome [in 455] and brought it to North Africa. It then made it to Constantinople. The Venetians may have taken it in the Sack of Constantinople of 1204, but we don’t really know.”

Jacov Di Segni, a rabbi in Rome, said that it’s no longer important to know where the furnishings are and if they still exist. “It could be risky, if someone found the menorah and used it as an idol,” he said in an interview. “Anyway, the Third Temple will be different, as we read in a description in the Book of Ezekiel.”

Nearly 2,000 years after the triumph of Titus, we can still picture the procession of the menorah, thanks to the famous carving—where the candelabra was originally painted a rich yellow ochre—on the Arch of Titus, built in Rome in 82 C.E.

*

While Jews across the world observe Tisha B’Av—a day of fast and prayer meant to commemorate the destruction of both the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem—it feels a little bit different here in Rome. The capital is home to the largest Jewish community in Italy, about 13,000 people, and they live with the Arch of Titus’s tangible (and imposing) reminder of the destruction of the Temple in close proximity.

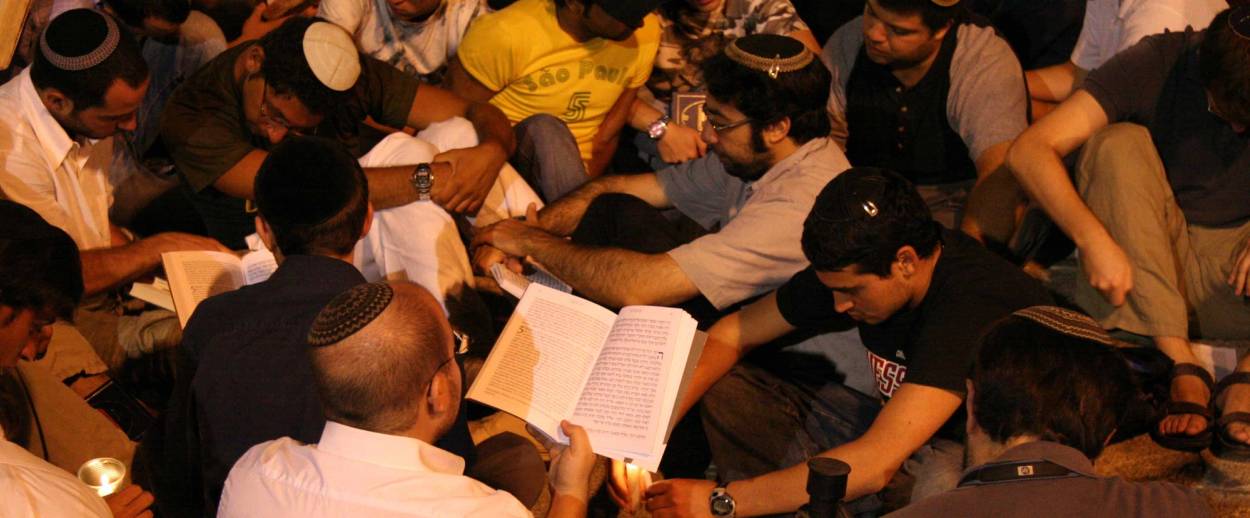

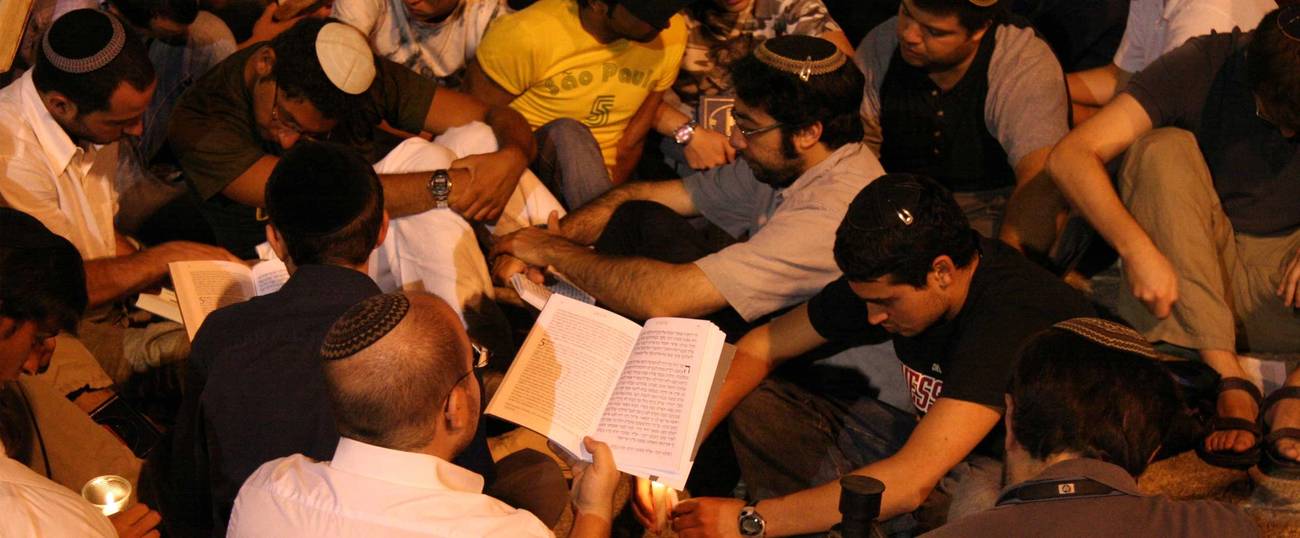

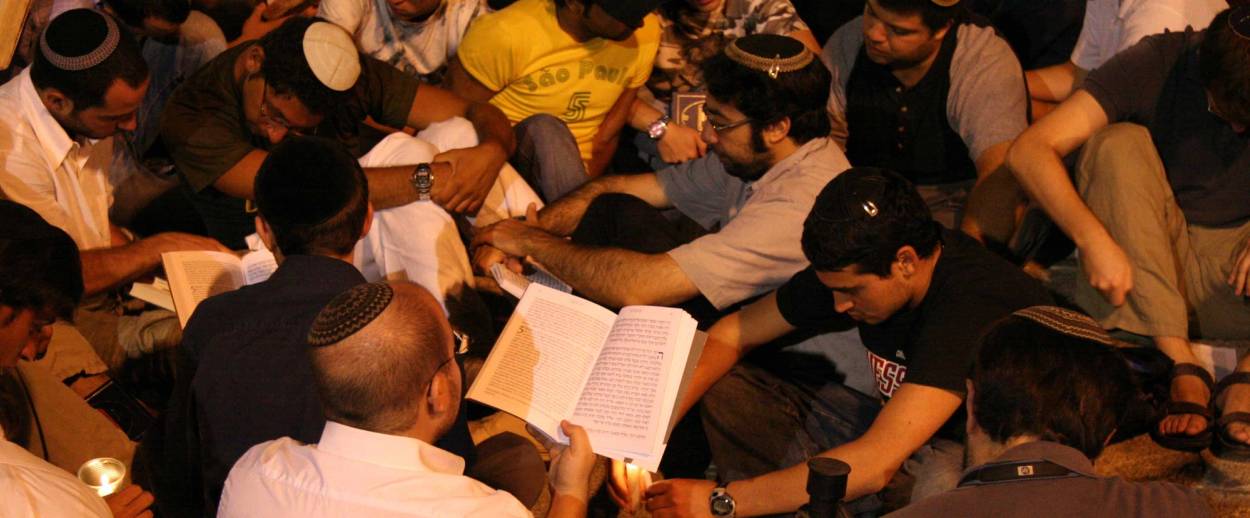

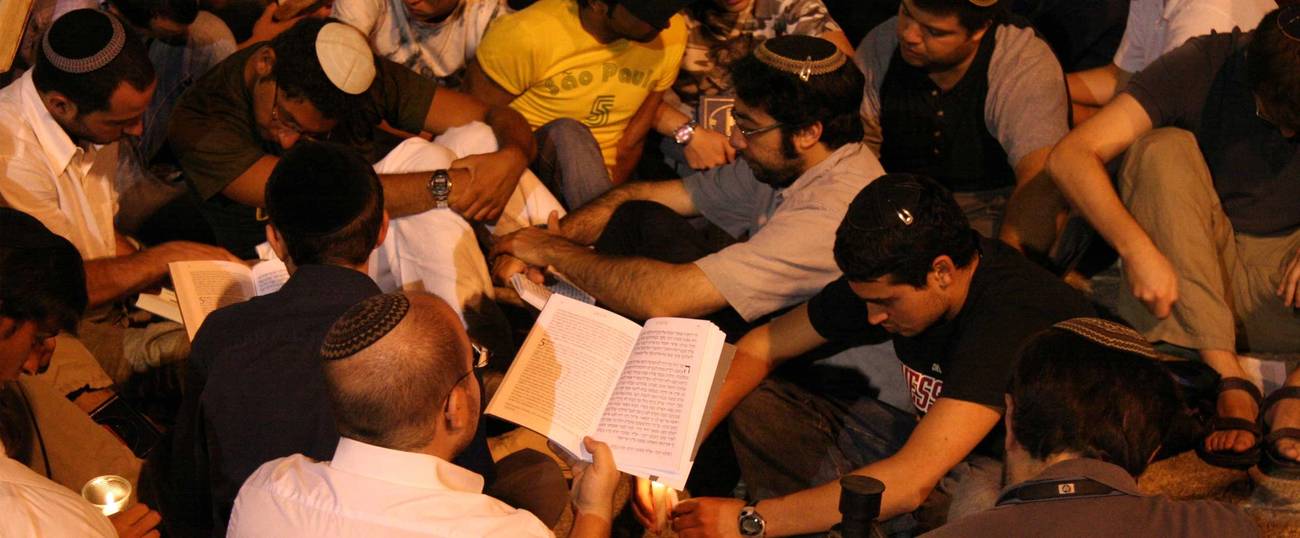

On the day of Tisha B’Av, the congregants of Rome’s Great Synagogue—one of the several Jewish houses of prayer in the city—sit on the floor of the right aisle of the shul. “It is the custom for someone who is mourning to change their seat in the synagogue,” said Di Segni. “On Tisha B’Av, the whole congregation is mourning, so everybody moves.”

All electric lights are turned off for the evening reading of Eicha, or Lamentations, the book from the Tanakh about the destruction of the First Temple. Everyone holds their own candle, which they use to follow the reading. Five different men respectively read the five chapters of Eicha with local tunes; the cantor recites the first part of each verse, and the congregants recite, in chorus, the rest of the verse, creating a participatory experience for the crowd.

At the end of the evening prayer, all the candles are blown out; only the cantor’s remains lit, as he recites a poem of Sephardic origins, “Al Echali.” “Over the Beit Hamikdash I cry, and remain in the dark,” the poem ends. As he says the word choshech, or dark, the cantor blows his candle out. It is a moment of great solemnity.

“When Rabbi Toaff sang this song,” recalled Di Segni, referring to the late former chief rabbi of Rome, “the entire shul was in the dark. He recited it by heart, with his candle unlit.”

Several other minyanim reunite on Tisha B’Av in Rome, as well as in other Italian cities, not to forget the iconic Italian synagogue of Rechov Hillel in Jerusalem, whose congregants meet every year at the Kotel for the evening reading of Eicha; it’s possible to listen to a recording of Eicha read at the Kotel using the traditional Roman tune.

Because Eicha refers to the destruction of the First Temple, it is common to read the kinnot, poems recited to commemorate several other tragedies in Jewish history, including the Roman siege of Jerusalem, the Crusades, and the Holocaust. However, Di Segni explained, some of Eicha’s references to the Kingdom of Edom are believed by some to be prophecies of the destruction of the Second Temple, since Edom was linked to Rome, according to the midrash.

The second verse of Eicha reads: “She weeps, she weeps in the night,” referring to the city of Jerusalem. A midrash quoted by Rashi explains that the repetition of “weeps” symbolizes the prophecy of the destruction of the Second Temple.

There is something that the religious and historical readings of this day have in common, said Rocca: that the great issue of the Jewish War was not the Roman siege, rather the civil war between different Jewish factions. “When the Romans came into Jerusalem, part of the population was already starving, since the Zealots [one of the factions] had burned a large portion of the food supplies. It is one of the most painful chapters in Jewish history.”

According to the tradition, God used the Romans as an instrument of divine punishment for the divisions among Jews.

Despite its difficult relationship with Tisha B’Av, Rome is also a place of hope for Jews. “We read in the Talmud that Elijah says that the Messiah will appear at the gates of Rome, among the poor and the sick,” Di Segni said. “The liberator is always in the home of the enemy—just like Moses grew up in Pharaoh’s house, or like Esther lived in the home of Ahasuerus.”

Each year, the Jews of Rome keep the stubs of the candles they use on Tisha B’Av, in order to use them a few months later to light the hanukkiah. It’s one step from destruction to reconstruction, year after year.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Simone Somekh is a New York-based author and journalist. He’s lived and worked in Italy, Israel, and the United States.