The Disappearing Apartment

A family of Soviet Jews prepares to leave for America in ‘Savage Feast,’ a new memoir with recipes

“You won’t live like that at first,” the woman at our dining table said, gesturing toward the closet, where her fur coat hung. My grandfather had insisted on helping her out of it, ostensibly out of chivalry but really so he could paw it and see what you could get in America. Chinchilla, she’d said, but he knew what he knew: That was rabbit. It was a good copy, though—the coat light, the hair dense. He had held the coat closet wide open so she could notice the blue German lamb’s wool there, the minks, the French shearling knee-length. He was doing just fine without the wisdom of people like her.

It was 1988—Soviet Jews were leaving in droves for America. (During this period, the word “leaving” came to refer to a single thing requiring no clarification.) That it was easier to leave didn’t mean it was easy—as always, only certain things worked at certain times for certain people. For instance, not only were letters from abroad getting through to us—opened and read, but with almost nothing crossed out—but the émigrés themselves were sometimes permitted to return and sit in former friends’ living rooms without ideological coaching, all while the authorities continued to menace and demoralize those trying to leave. But we had slipped through. On this go-around, my father and grandfather went into the visa office when called. We were leaving, and we wanted to know what to expect.

My grandmother didn’t know how to set the table for our guest—would Soviet food seem paltry next to the glories to which this former countrywoman now surely had access in American supermarkets? My grandmother decided on the opposite of what she had served all those years ago to the safety instructor from my father’s technical college: In times of uncertainty among kinspeople, lean on the Jewish regimen. Dill-flecked chicken bouillon with kneidels (matzoh balls, from matzoh baked and delivered by secret couriers at night); a chicken stuffed with macaroni and fried gizzards; the neck skin of several chickens tied together and stuffed with caramelized onion, flour, and dill to make a sausage-like item called helzel. For excess, there was deconstructed, or “lazy,” stuffed cabbage—everything that would have stewed inside a cabbage leaf shredded and shaped into patties instead—and a chicken rulet: a deboned chicken layered with sautéed garlic, caramelized carrot, and hard-boiled egg, then rolled up and fastened for cooking with needle and thread. It had a noble pedigree: In 1941, with the Nazis beginning to starve Leningrad, the Soviets discovered two thousand tons of mutton guts in the seaport and made rulet out of them. As always, my grandmother made too much, but you had to show you didn’t lack for things.

“You’ll have to eat a little shit to start with,” the woman went on, wiping her mouth; on sighting the food, she had forgotten her queenly hauteur. “But one of my friends owns a Hallmark franchise—greeting cards—and would you like to know what she hauls in in a day?” She allowed a pregnant pause to expire. “Two thousand dollars.” My mother, eager to show gratitude, gasped in wonder. My grandfather selflessly refrained from raising his hands in mock worship—he had the equivalent of that in his pocket right now. My father uncrossed the arms he liked to keep at his chest in a kind of preemptive objection. “But what about crime?” he said. “It’s all they show on television.”

The woman swished around her bracelets. “I walk like this all the time,” she said. “Just don’t bring hats. Everyone has a car and drives everywhere, so you don’t need a hat. If you’re wearing one, that means you’re an immigrant. In fact, don’t bring anything. They have everything there. And it costs next to nothing.” Perhaps it was because my grandfather couldn’t tell this highhanded hag what he really thought that the first thing he stuffed into our luggage was the gray mink hat that sat on his head from September to April.

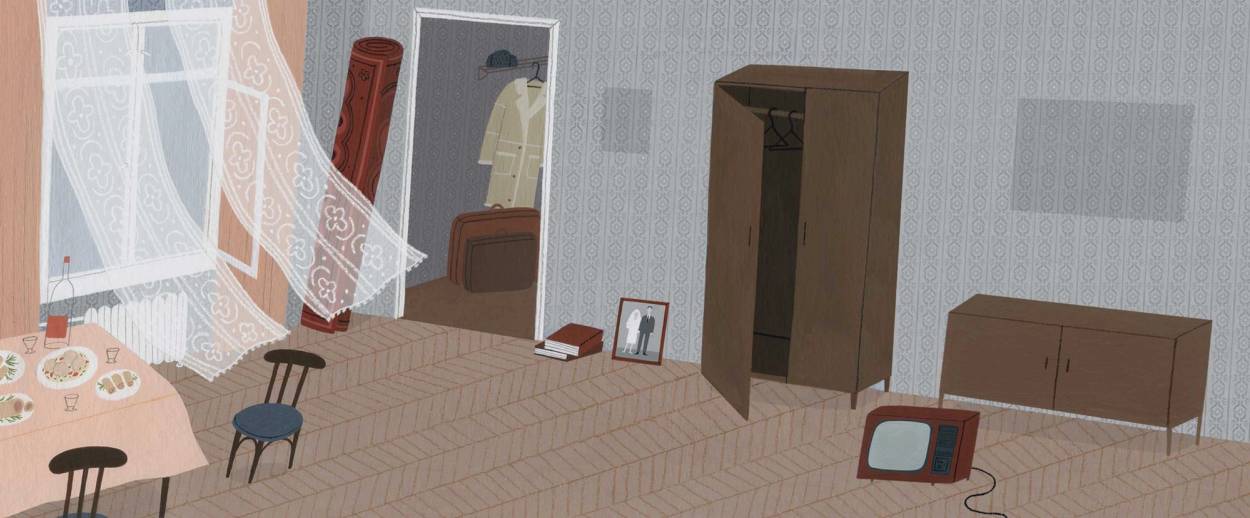

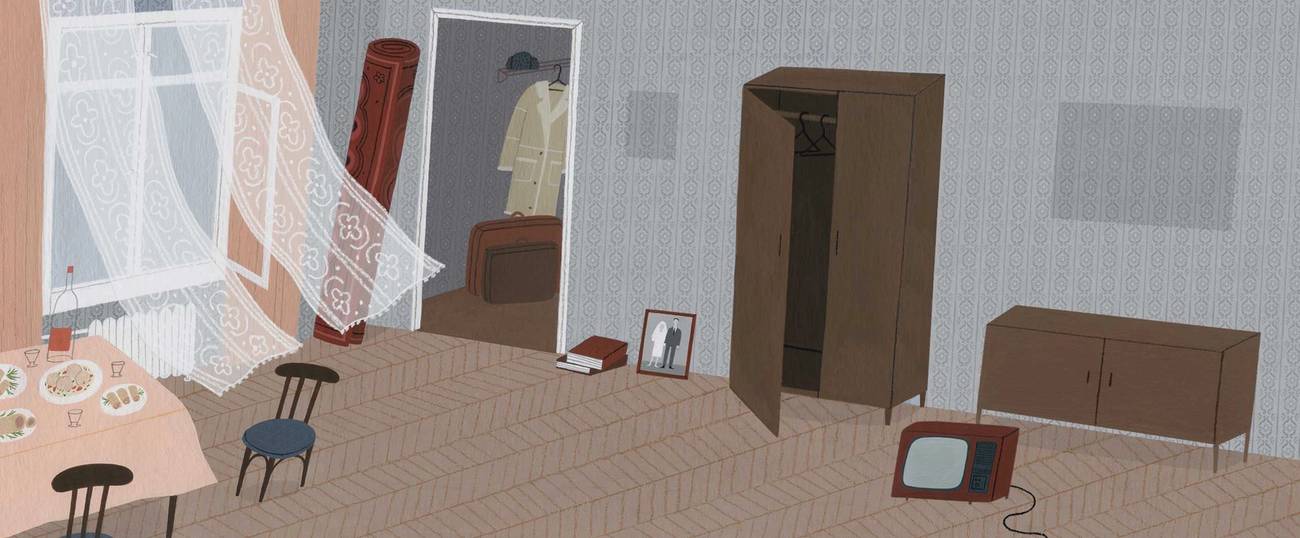

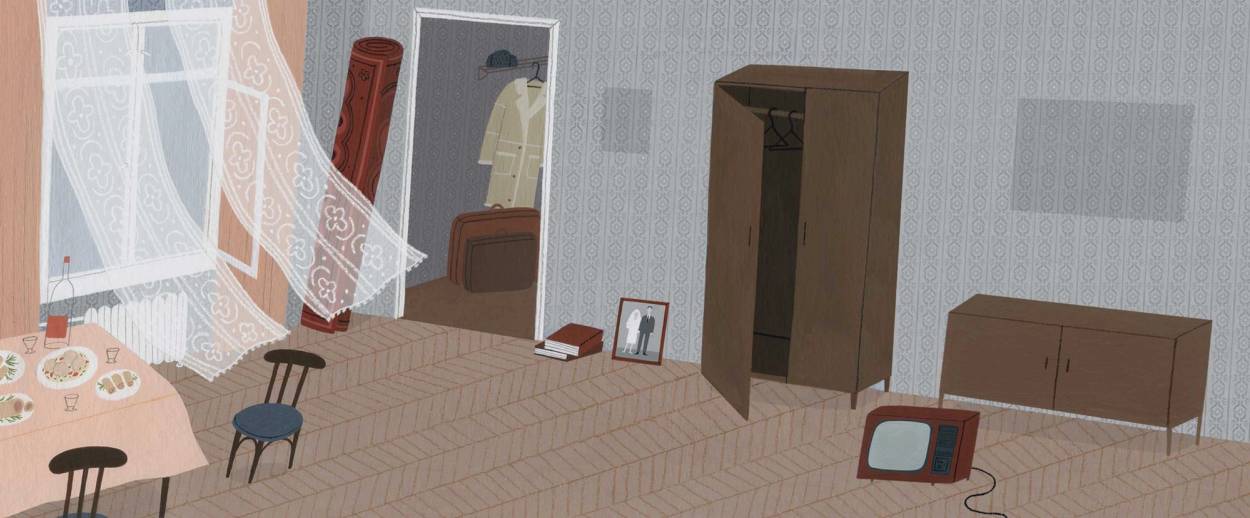

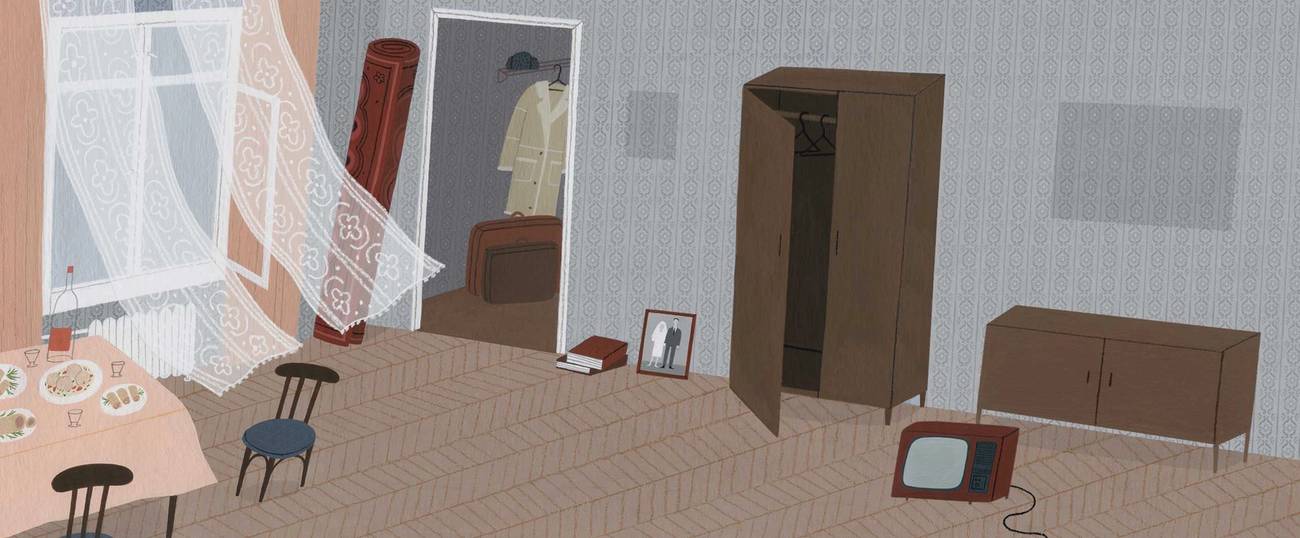

It was like one of my father’s strange fairy tales: Little by little—for free, for favors, for pay—the apartment began disappearing. The vanishing of the television, taken by one of my mother’s co-workers, caused me special grief. When my grandfather and I weren’t “polishing” the cold concrete seats of the soccer stadium itself, it was where I watched Dinamo Minsk go up against Zenit Leningrad and Torpedo Moskva. The separation of twenty-two previously indistinguishable men into two adversarial uniforms, the pride of a city behind each, was a gnomic, primitive message from some other dimension in which, as the pig slaughterer whose summer cottage we rented had so essentially put it, “there will be you—and there will be them.” The television alone knew my guilt for rooting—the Russian word is bolet, to be ill for—for the Finns instead of the Soviets in hockey. The Finns had such mellifluous names, vowel after vowel, like Arctic Hawaiians. And they were so clean and crisp in their white-and-blue jerseys, so calm against the tense red of ours. They looked like our players—tall, fair-haired, light-skinned—but without the roughness and disfigurement of our faces. Disfigured by hockey, but also by how we ate and drank, by the expressions into which our faces were fixed.

My bookshelves were attached to the wall, so I believed they were safe, but one day they were gone, too. Then the Persian rug on which, on all fours, I read the sports pages. Then my bed. The kitchen went last. A friend of my mother’s hauled away everything in it. They agreed on a price, but the woman gave us no money; she had a relative in America, and since each emigrant could take the equivalent of only $90 in currency (and $250 in possessions), the woman’s relative would pay 50 percent of the agreed-upon price when we got to America—for us, a way of getting out more currency than was allowed. Our position was weak: Who knew if the phone number the woman scrawled on a piece of graph paper corresponded to an actual human. But if it did, that poor person had to shell out money on behalf of a Soviet relative for nothing in exchange. So 50 percent was the actuarial measure of the exposure and risk for all involved.

You can sleep on the floor, but you can’t eat the air; how to survive without a stove or a fridge? For the first time in my life, I experienced the dread of not knowing from where the next meal would come. No one had explained that those relatives and friends who did not fear associating with us—“men would not come to our plague-stricken house, but sent their wives instead,” as Nadezhda Mandelstam, the condemned Soviet poet Osip Mandelstam’s wife, wrote in more severe circumstances—would come with everything from utensils to foldout tables. My aunt brought braised beef with cubed potatoes and marinated peppers; blintzes stuffed with ground beef and caramelized onion; and a chicken stuffed with crepes and more browned onion, then roasted. All this disappeared quickly. Departures like ours meant more helping hands, but also more mouths.

Though my grandparents’ home never lacked guests, this was a different kind of assembly. The smartest people congregated in the kitchen, where the constant replenishment of the foldout table turned the day into a single, unbroken meal. But there were people standing—with glasses, or arms folded, or consoling hands atop grieving wrists—in every room, even mine. (Evidently, its emptiness had re-registered it as common property.) Periodically, these congregants would make a pilgrimage to the kitchen like steam bathers who’d spent too much time in the cold and down thimbles of cognac or vodka. Often, no one had to be anywhere in particular. There was nothing to do in the Soviet Union other than the obscene number of hours you spent queuing for food. You could go to the cinema, you could go for a walk in the park, you could watch a sporting event, and on a special occasion you could splurge in a café. Otherwise, you sat in people’s kitchens, ate, drank, and talked.

The apartment hummed with festiveness, nerves, and anticipation. Even my father strode around with a strange gregarious bloom. Not long before, he had kicked in the television—the thick, greenish glass shattered—and vanished for days. Nothing was explained to me—a new TV appeared right away—but I knew it had to be another argument about my grandparents making all the decisions, and was filled with anguish. But now he and my grandparents smiled and laughed with each other. How? The only thing my father hated more than too many people was falsehood.

People came and went, but my grandmother’s older sister, who never took vacation days and disliked socializing even more than my father, came for the entire day every day, which indicated just how extreme our situation must have been. As did the rolls with sugar and cinnamon she brought, still warm, the crowns shining with egg wash like little brioches—you never saw extravagance like that from her.

The war had orphaned the two sisters. When the Nazis invaded, their grandmother, not a slim woman, had squeezed behind the furnace and suffocated herself. Their parents and grandfather were killed in the pogrom that finished off those Jews in the Minsk ghetto who had survived the previous three. (My grandmother had managed to slip out the month before, but her grandfather was ailing and her parents would not leave him.) When the sisters returned home after the war, they found it occupied by an ethnic Belarusian who had collaborated with the Nazis. He gave them a corner. When they were out one day, he stole and pawned all the clothes the Red Cross had given them, leaving one dress apiece.

This affected the sisters very differently. My grandmother became flamboyant and unsparing, her hair half a foot high and her nails always painted; my grandmother’s sister was humbly clothed and allergic to makeup. She took advantage of none of the private perks of the government job she got after going back for more school after the war. She barely touched food. Held on to every ruble. Didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, didn’t laugh with everyone else. If her son was going to the theater, she had to go there after curtain to check that his coat was on one of the hangers and that he’d arrived safely. (Soviet cities not having anything like American traffic or sprawl, it didn’t take her long to get there and back.) In the evenings, the young man hardly late, she’d begin calling police precincts and hospitals. To her husband, his family already lost to Communist purges by the time the Nazis arrived, nothing was holier than fresh lamb “forgotten about” at low heat for hours, or slices off a crescent of veal tongue with horseradish and chased with cold vodka—his last name was actually Golod, “Hunger”—but she always badgered him to cook less. She didn’t hug my grandmother, didn’t kiss her. But they had sat in each other’s kitchens almost every day for forty-five years.

Her severity had its uses. Every fall, when the cabbage came in, the cellar disgorged a contraption resembling a cross between an ironing board and a giant mandolin, through which the women ran giant heads of cabbage, shreds leaping into the air like wisps of hair when my grandfather barbered. These went into jars the size of a boy’s torso, with peppercorns, bay leaves, rings of onion, and cranberries. When they reemerged, a month or two later, they bit the tongue in a way that was rare during those dead winter months. It was a group job, but when my grandfather’s brother appeared to “help,” he sat down and filled the kitchen with bitter, cheap smoke, which meant the kitchen window had to come open, which meant the boy might catch cold. So he was eased out. Then his daughter came and drank instant coffee and dropped rumors. She was less harmful, but useless, so she was creatively disappeared as well. The job “moved” only when it was my grandmother and her sister.

Aunt Polina was so undone by my grandmother’s leaving that she even let her husband bring his tongue and braised lamb. Making the most of his rare dispensation, he sneaked in a new pièce de résistance: potato latkes drizzled with goose fat and honey.

The various discouragement taxes remained in place: It cost seven months’ salary per adult to renounce citizenship. The white identity papers we received in exchange were so flimsy that someone figured out how to doctor them: Move up the birthdate and retire sooner in the States. We were all becoming new people; no one needed to know. But the bejeweled and false-furred acquaintance who had visited from America had said no one lied there. If you did, your name went into a file. To a Soviet person, that made perfect sense. My father said no to the age adjustment.

Émigrés were allowed to ship things forward, but the boxes were rummaged at Soviet customs. People who owned diamonds threw them like beads into the boxes and container units they sent—they might never find the diamonds, but neither might customs. Those shipments that made it to New York encountered new, American dangers—two boxes of my father’s construction equipment were stolen out of the trunk of the relative who received them.

After the construction equipment, we sent nothing ahead. Our visitor had said America had everything, and for pennies. So we crammed a century of Russian life into five suitcases. The things we carried included a single photo of my parents’ wedding; my checkers set; cupping jars and mustard plasters; the cobalt West German tea set; Italian enamel cooking vessels; my grandfather’s French shearling coat; and three books, the comedians Ilf and Petrov sandwiched by Bulgakov and Pushkin. (This was an American sandwich—Soviets ate only open-faced sandwiches.) And we carried everything we had been told would sell in the secondhand markets outside Rome, the next transit point after Vienna: electric drills, Zenit cameras, peaked army caps, Lenin pins, good Soviet linen, Armenian cognac.

We did not carry my mother’s wedding ring, alone worth more than the allowed limit per person; the Yugoslav entertainment center; my grandmother’s Finnish leather boots; my mother’s Austrian suede heels; my grandfather’s collection of Italian leather shoes; Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas, or the Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg; my mother’s wedding dress; or the ice skates I never learned how to use. Outside of his tools, my father possessed almost nothing and so had nothing to part with. But we also did not carry the cast-iron cooking pot. It was too heavy. It would have made one last loss to that place that had already taken so much, were my grandmother Faina not more than happy to have it back in her hands.

From the book Savage Feast by Boris Fishman. Copyright © 2019 by Boris Fishman. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

From ‘Savage Feast’ by Boris Fishman

My Aunt Lyuba is one of those fabled ex-Soviet women who can “cover” a multicourse table for a dozen guests in an hour without advance warning. This dish takes a little longer but is worth the trouble for an unusual, homey take on a roast chicken.

4 tablespoons vegetable oil, plus additional for the pan

1 1/2 onions, chopped

Kosher salt and black pepper, to taste

1 1/4 cups milk

1/4 cup water

4 large eggs

2/3 cup flour

1 teaspoon sugar

1/4 teaspoon salt

1 whole chicken, 5-6 pounds (a larger chicken means a larger cavity for stuffing)

1. Heat 2 tablespoons of the oil in a pan over medium-low heat. Add the onions and cook, stirring once in a while, until golden brown. Season with salt and pepper.

2. While the onions are cooking, make the batter by mixing the milk, water, and 2 of the eggs. Then whisk the flour in, little by little. Then add the sugar and 1/4 teaspoon salt. And finally, add the 2 remaining tablespoons of vegetable oil, whisking well. Your batter should be pretty liquid.

3. Warm up a small (8- to 9-inch) crepe pan or nonstick skillet over medium-low heat. Add a tiny amount of oil (or cooking spray), give it a little time to warm up, and roll it around so it covers the whole pan. Raise the heat to medium.

4. Lift the pan off direct heat—otherwise the batter sticks too quickly—and add enough batter that it expands to the edges of the pan (around 2 tablespoons), swirling the batter until it forms as perfect a circle as possible. You want a thin crepe, so try to add as little batter as necessary to reach the edges of the pan after swirling. Return to direct heat.

5. After 2 minutes or so at medium heat, the crepe should be sufficiently browned underneath and crisp around the edges for you to be able to use a spatula or a fine-tipped wooden skewer to lift it. Now you have to flip it to the other side. The difficult truth is that there’s no better instrument than your fingers, if they can withstand the heat.

6. If the crepe tears, don’t worry: The first crepe always comes out sideways, as we say. You can “darn” the hole by pouring in a little new batter to fill it. Either way, this is a forgiving dish for ugly practice crepes—they will end up out of view. After 2 minutes on the other side, the crepe should be ready; set aside and repeat with the remaining batter.

7. Stack the crepes on top of each other and cut into quarter-inch-wide vertical strips, and then cut those strips into thirds horizontally. Mix in a large bowl with the cooked onion, and then add the 2 remaining eggs. Mix thoroughly.

8. Preheat the oven to 450 degrees. (The high heat will give the skin a nice crispness.) Rinse the chicken and pat dry. Season generously, inside and out, with salt and pepper. Then fill the cavity with the crepe-and-onion mixture, closing the skin flaps around it as much as possible. Lay the chicken down gently in an oven-worthy pan, breasts down so they absorb the dripping juice and the fat of the thighs. Cook for 10-12 minutes per pound, until the juices from a thigh run clear when pricked with a fork.

Time: 2 hours

Serves: 6

Boris Fishman is the author of the novels Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo and A Replacement Life, and Savage Feast, a family memoir told through recipes.