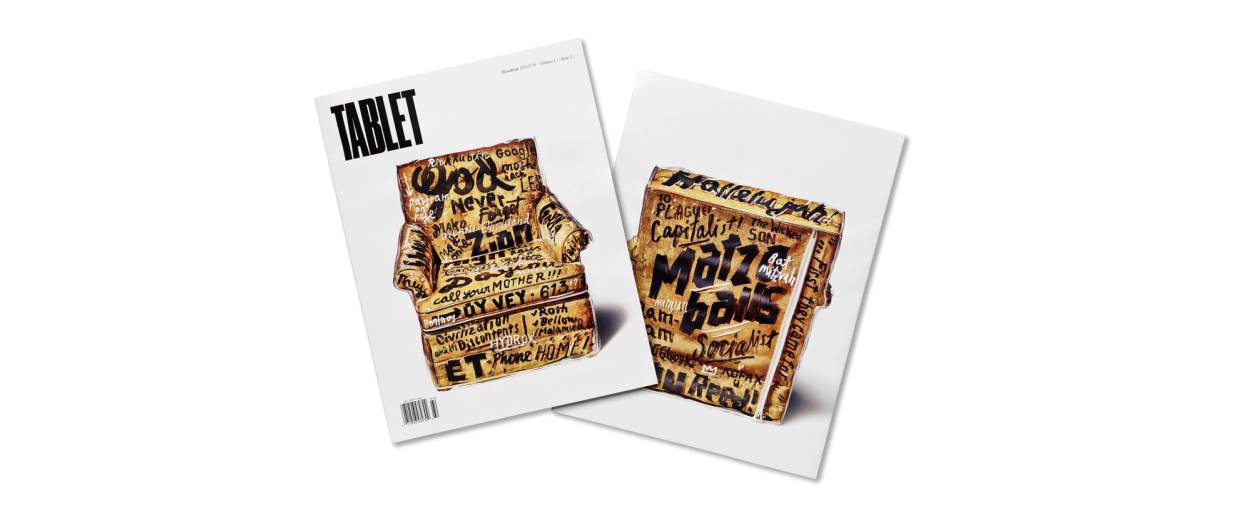

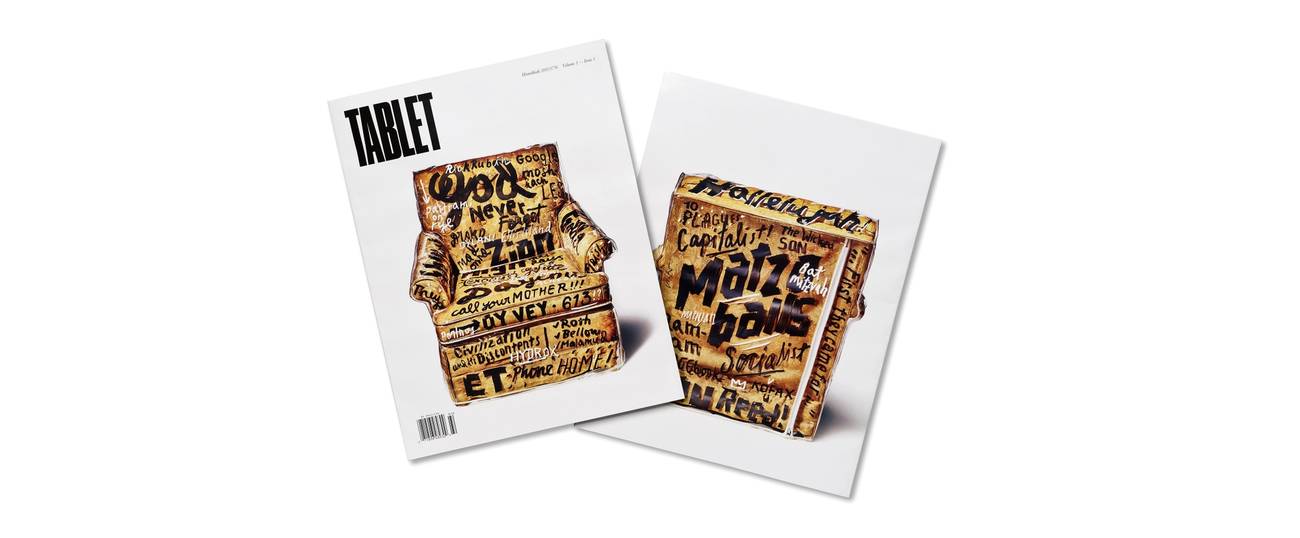

This Magazine May Not Be For You

Editor’s Letter: Introducing our new print publication

A good magazine, the kind you pick up more than once, starts and ends with good stories, the sort that teach you something new, make you laugh or cry, or show you familiar things from an unexpected angle. So, I might as well tell you a story. Or rather, I’m going to have my husband’s Uncle Myron tell you a story. They’re not related by blood, I don’t think, but Jewish history kind of pushes us to grab at whatever live relatives we can. Myron is an energetic man who wears Kangol caps and works in what David has described to me as “the coin-operated machine business.” Anyway, here goes:

“1965. I remember going down to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. I was doing business with a Southern gentleman who I later found out rode with the Ku Klux Klan when he was a youngster. He later became one of my best friends, one of the most trusted guys on the face of the earth, an outlaw like myself. Now, this man had a wife and kids—four kids—and he had three other concubines. He would eat Thanksgiving dinner in four different states. Amazing man. The last concubine had one child, a daughter, who ended up going to Columbia University—she never really knew her father too well. She became like a daughter to me.

“Anyway, to make a long story short, I went to jail. While I was in jail she used to send me letters about Judaism. To make another long story short, this girl converted. Nine days after she converts, she meets her bashert, her beloved, and gets engaged. They wound up getting married in Safed, Israel. Got married in a Chabad wedding—you know a Chabad wedding where they put the sheet over the girl’s head? One of those. Know what my friend said to me—her father, the Confederate? He says, ‘We used to put sheets over our heads, too! While we were riding with the Klan.’

“It gets better. His older grandson’s brit milah was held at 770 in Crown Heights. And my friend showed up there, they put a kipa on his head, and he’s waving a yellow flag that says ‘We Want Moshiach Now.’ His wife says to me: ‘Can you believe this? This son of a bitch—he rode with the Ku Klux Klan, and he tells you and me that his best customer was the Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan of Mississippi. And look at him today, on top of someone’s shoulders waving a yellow flag that says, “We Want Moshiach now.” ’ ”

Now, if we were on the Internet, you would all start tweeting nervously at me from your respective pigeon holes. “Don’t glorify the Confederacy!” “Don’t glorify gangsters!” “Don’t glorify … Chabad!” Luckily we’re not on the Internet here, so you can all admit what you’re really feeling, which is that this is just a damn good story about Jews—whatever it’s supposed to mean.

***

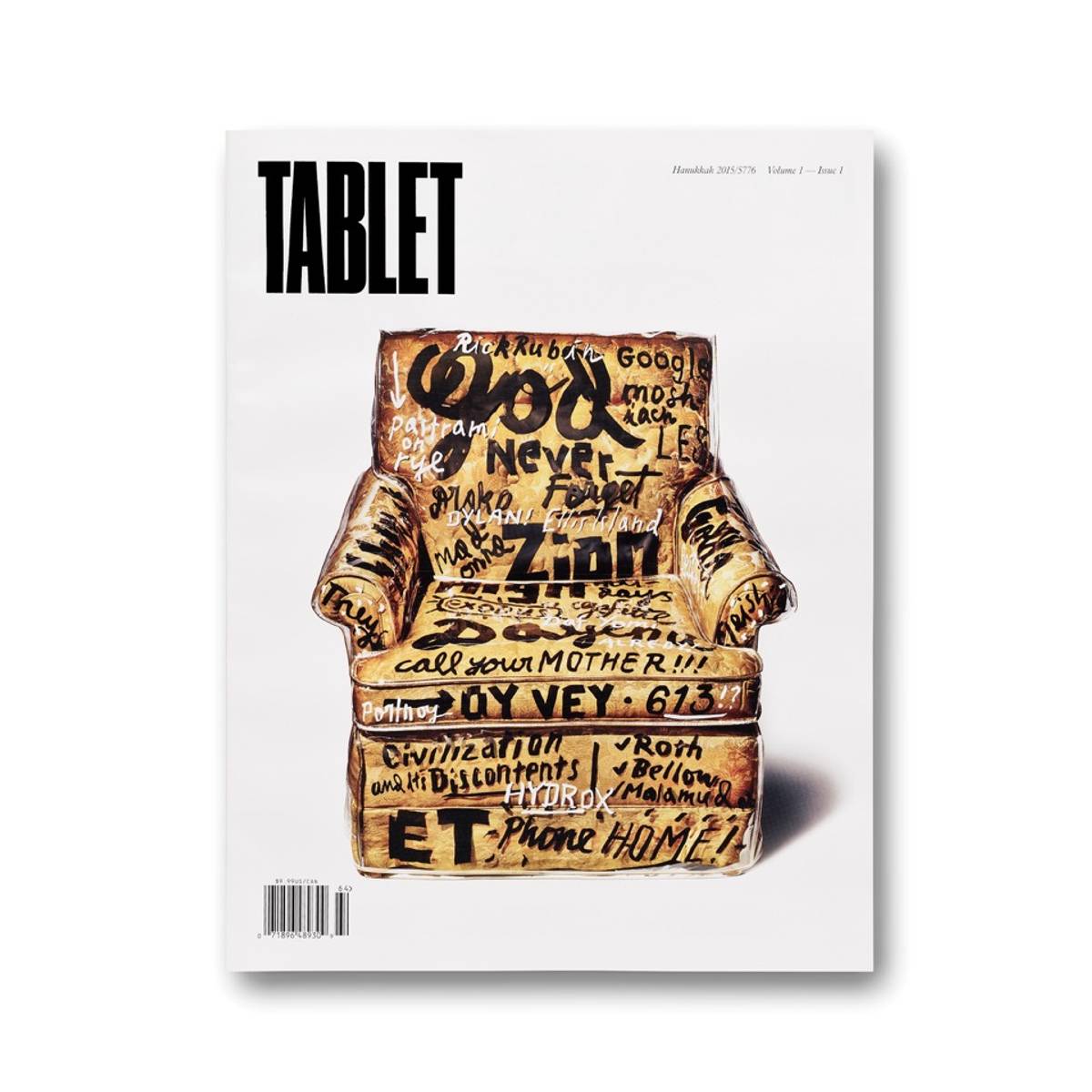

When I was growing up, magazines were still hot to the touch—by which I mean, many still followed the imperative to be something specific, even (or especially) at the risk of alienating some potential readers. They took pride in their specificity. Each one was a party, but for a particular group of people. Over there, a small gathering of writers with

exquisite literary taste and embarrassing politics was having a dinner of chicken and white wine; in that SoHo loft, a flock of handsome neurasthenics in black turtlenecks smoking on the fire escape while debating graphic design; fashionistas glittering in dark banquettes; black writers and editors chatting in some fabulous Arthur Elrod sunken living room; gin-soaked WASPs holding court at the far end of the hallway, near the fireplace. And so on.

They were flame-throwers, all of them—each in their own way. They liked coming up with angles that were both smart and also anxiety-producing for their readers, of whom there were few enough that the editors and writers on staff could custom-design content. It was this specificity, in fact—the ability to assert a singular point of view confidently, even at the risk of being obnoxious—that made many of these magazines so deeply sexy and that made general-interest titles seem like dutiful if no doubt healthy walks in a public park. There were a lot of problems with this era, of course, and the problems got worse as these smaller magazines decided to vie for bigger audiences—which made their claims on some exclusive personality both wrong and also insulting to prospective readers. And the Internet happened, which may or may not have caused or exacerbated the decay, but the bottom line is that magazines today aren’t what they used to be. Someone asked me recently: “Where is the Kanye West of magazines? You know: a magazine as frequently brilliant as it is insufferable and ridiculous, and therefore demanding of our attention in order to figure out which is which.” On Twitter a few days later, I saw a magazine writer offer her own lament, which serves in a way as an answer to this question: “No safety = no risk.”

If anyone knows from this kind of lukewarm bath water, it’s American Jews, because it’s what our communal representatives have trafficked in for decades. For what it’s worth, it hasn’t done us any favors. What many of us have been left with is a sense that our institutions have achieved the impossible: No matter what political or religious or cultural place they come from, an unfathomable number of them share the seemingly impossible combination of being both remorselessly condescending and also deeply milquetoast. Like many magazines today, American Jewish life has sometimes felt like a Telegram from Everywhere—which is nowhere, of course.

***

A big part of what has made Jews and Jewishness so magnetic—in both the positive and negative senses, for Jews and Jew-lovers as well as anti-Semites—is that Judaism has historically been two things at the same time, which don’t easily fit into modern definitions of identity: a tribe and a religion. One’s tribal affiliation isn’t something one has to work at, nor is it something one can slough off. You are born into it. Religions, in some senses, work the opposite way, at least in America; membership is usually determined by observance, and people can and do flow in and out at will. Though many do not quite understand the contradictory valences of the word Jewish, it’s what’s caused our contemporary situation—in which various people create or profess identities that are based not simply on differing levels of observance, but on different definitions of what Jewishness even is.

This explains why, in the current American conversation about identity, Jews (and others) often have diametrically opposed perspectives. To some, American Jews are effectively insiders: Since America’s unique flavor of bigotry has historically been based on skin color, and since many believe that all Jews have white skin or can easily “pass” for white, Jews are therefore imagined to have the emotional experiences of privileged white people and should shoulder the responsibilities to others that rightfully come with having had this historical and continuing advantage. To others, Jews have been outsiders nearly everywhere they lived, for thousands of years. We come from places with long traditions of brutal hatred, and we live here now with the damage of those experiences. In the last place Jews felt at home—which wasn’t that far or long ago—our neighbors didn’t care about what we looked like; instead, they went hunting back into our DNA logs for proof of who we were and shipped those who fit the bill off on cattle cars to gas chambers. And anyone who believes that that story ended in 1945 when a shocked world woke up to the consequences of its Jew-hatred hasn’t been reading the news from Paris lately, or the reports from Tehran, or even some of the stuff that now regularly gets printed in American newspapers.

Somewhere between decades of stale leadership and the shifting landscape of global ethnic and religious identity, a lot of American Jews became duller—in every sense. Fleeing from both the lived experience and the deep knowledge that sustained communal existence, many of us have taken refuge in some combination of an unearned sense of entitlement (“Did you know that Jews constitute almost one-fifth of all Nobel laureates? This, in a world in which Jews number just a fraction of 1 percent of the population!”) and an increasing provincialism—even among people who otherwise consider themselves sophisticated. For the past decade, it’s been my job to get mail from Jews, and let me tell you: You are all convinced that your entirely subjective assumptions about how Jewishness functions in the world are The Truth. Hollywood Jews read some American Jewish Committee press release about the Iran deal and become stricken with fear that everyone thinks all American Jews are right-wingers; right-wing Jews believe everyone is out to get the Jews, when in fact most people (in America, at least) couldn’t care less; left-wing Jews think AIPAC is monolithic and all-powerful, when the truth is it hasn’t actually had real power for years; Orthodox Jews are convinced that all non-Orthodox Jews don’t venerate Jewish history, whereas non-Orthodox Jews think the Orthodox look down on them because they don’t observe; everyone believes New Yorkers don’t have the faintest interest in, or respect for, Jewish life outside of Gotham, when the exact opposite is true. (One can visit Orchard Street only so many times, you know.)

Also, a lot of you say things like, “I’m really not very Jewish,” as though we still live in the 1950s and you’re worried Muffy from the club (or Jared from the food coop) might see your ethnicity showing. I have to believe that most of you feel uncomfortable uttering such self-negating words. But for starters, let’s say that this magazine is not for people who say stuff like that and mean it.

In fact, we’re not for people who believe in orthodoxies of any kind. We’re not for the man who can’t stand being in the same space as people who disagree with his politics, whether he is voting for Bernie Sanders or for Donald Trump. We’re not for people who can only imagine what it is like to daven on their side of the mechitza, and we’re not for people who can’t imagine talking to anyone who would daven at all. We are a magazine for people who are curious. Jews, half-Jews, former Jews, Jewish wannabes, non-Jews who like Jews—people who, regardless of their politics or religious level or how much money they have or where they’re from, are searching and interested and curious about Jewishness and how it

functions in the world.

If you’re one of these people, well, we’re having a get-together and you’re invited. You’ve been warned, though: There will definitely be people here who aren’t like you, whether they’re religious or secular or left-wing or right-wing or rabbis or writers or historians or movie stars or gangsters (or Klansmen, I guess). And you will probably be annoyed and provoked as much as you’ll be enlightened and entertained. If you’re into that, definitely join us. We’re the Jews at the big table. With the food.

This Editor’s Letter appeared in Vol. 1, Issue 1 of our print magazine, published Nov. 11, 2015.

Alana Newhouse is the editor-in-chief of Tablet Magazine.