A Brilliant Magpie

The new documentary ‘Eva Hesse,’ opening this week, explores the too short, too beautiful life of an art heroine

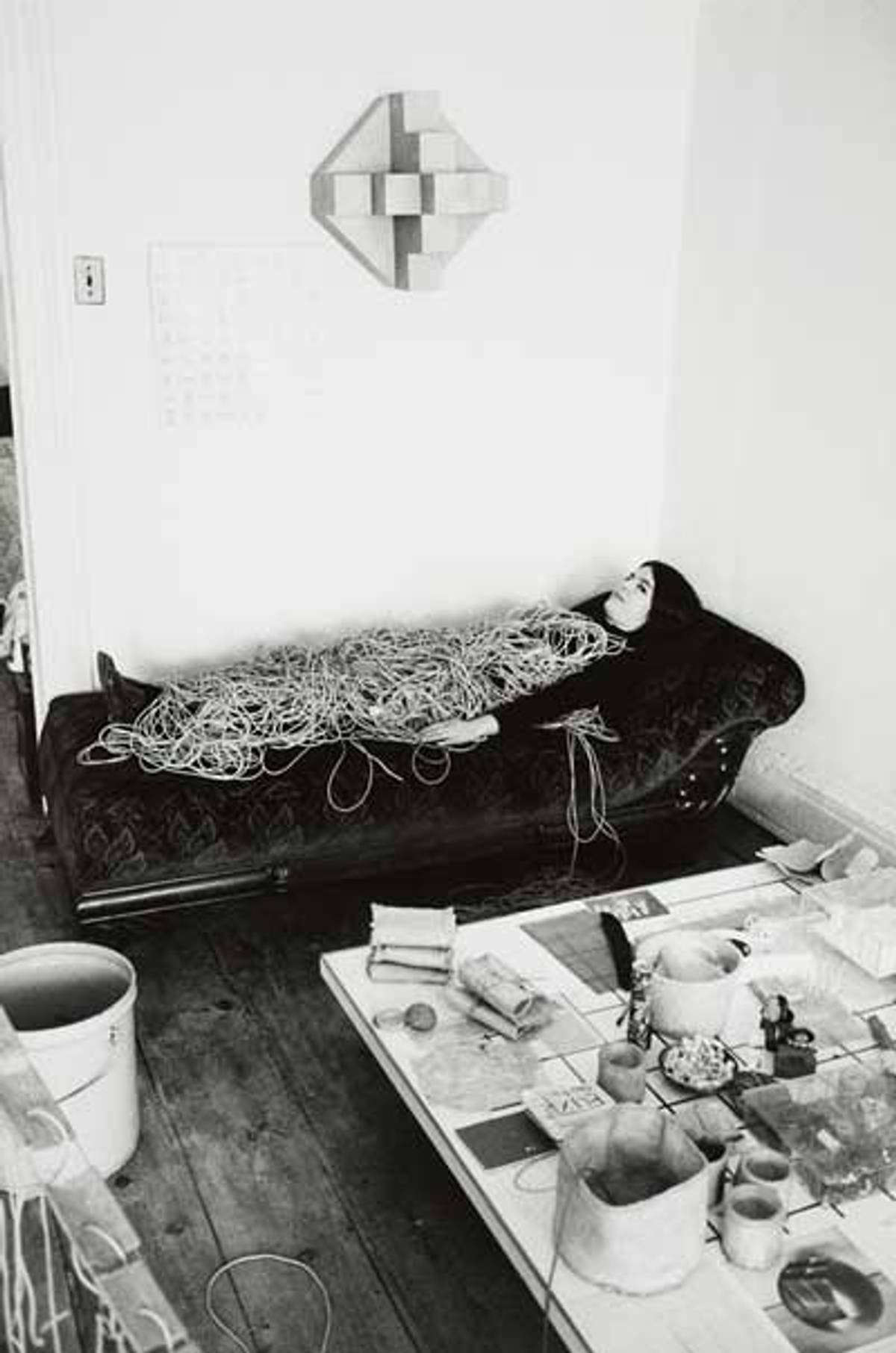

Had she lived, artist Eva Hesse would have turned 80 this year. But lovely-looking, dark-eyed, and dead at 34, she personifies transitory beauty. So does her groundbreaking work—serial arrangements of biomorphic tubes, webs of latex coated rope, fiberglass stalactites, and wire clouds—which, hell on conservators, seems largely about its own evanescence.

“Eva Hesse was one of the greatest artists of the 20th century,” the curator Elizabeth Sussman declares early on in Marcie Begleiter’s new documentary, named for its subject. Given the brevity of Hesse’s career, one might wish to change “greatest” to “most brilliant” or modify the word “artist” with “American” and “20th century” with “late” but there is no question that Hesse had one of the 20th century’s more compelling life stories.

Published 18 months after her death, the lead piece in the November 1971 issue of Artforum, “Eva Hesse: Post-Minimalism Into Sublime,” shattered the magazine’s precedent by putting Hesse’s personal history up front. The article, which was written by Robert Pincus-Witten (a critic who would later write several essays on the nature of Jewish art), began “Eva Hesse was born in Hamburg, Germany to a Jewish family on January 11, 1936—in full Hitlerzeit.”

Hesse made a childhood escape from Nazi Germany, where her extended family was largely exterminated, only to die young of a brain tumor. In between there was her chronically depressed mother’s suicide, an unhappy marriage, much psychotherapy, and five years of astonishing productivity with escalating recognition. Pasted by friends to the wall of her last hospital room was the cover of Artforum’s current issue. It featured her piece “Contingent”—eight suspended sheets of latex-covered cheese cloth, at once tough and fragile—bathed in a golden light.

***

Hesse was a charismatic figure during her lifetime. (One can well imagine that half the art world had a crush on her; after seeing this movie, I developed one as well.) In death, she has inspired passionate adoration. On the occasion of a major retrospective in 2002, art historian Katy Siegel called her “a heroine in college art departments, not unlike Frida Kahlo or Sylvia Plath.” Begleiter is one devotee. Eva Hesse the movie was preceded by a theater piece, Meditations: Eva Hesse, involving nine performers and multichannel video, that premiered in Los Angeles in September 2010.

Nearly half Begleiter’s theater piece represents the last day of Hesse’s life; the rest concerns her recollections of the preceding 25 years. By contrast, the documentary Eva Hesse begins in the early 1950s with Hesse as an introspective teenager passionately determined to become a painter. Unsuited to her first art school, Pratt, she thrived at Cooper Union and later attended Yale where she studied with Josef Albers.

In the interregnum between Pratt and Cooper, Hesse interned at Seventeen magazine—an apprenticeship that may have been as useful as art school. Not only was the neophyte painter the subject of a profile published in the magazine, it’s reasonable to assume that working there she also learned something about self-presentation. Few artists have ever been more photogenic. Had she been in New York in 1964, Andy Warhol would surely have wanted her for a screen test. With her long braided or upswept hair, dangling earrings, and ethnic chic, Hesse perfected a haute beatnik look that would serve her for most of her short life. (She actually worked for a time in an Eighth St. costume jewelry store.)

Hesse thought like a beatnik as well. She admired Jean-Paul Sartre and Samuel Beckett and in a 1970 interview with Cindy Nemser that would be her longest public statement, asserted “my whole life has been absurd.”

As an artist, Hesse was a bricoleur who absorbed what was in the atmosphere and refracted it through her own sensibility. Returning to New York in 1965 after a year in Europe, she successfully synthesized the newly ascendant minimalist and serial tendencies with a witty form of eccentric expressionism and a subversive use of new materials. “Ishtar” (1966), named for the Babylonian goddess of love, is a board with 20 breast-like hemispheres, each extruding a black plastic cord.

Begleiter makes much of the inspiration Hesse took from New York’s Canal Street, a grungy bazaar for all manner of hardware, plumbing supplies, plastic scraps, and unclassifiable widgets. Coincidentally, I became familiar with Hesse’s 134 Bowery studio, a block above Canal Street, in the early 1970s when it was occupied by friends of mine (although I don’t believe we knew then that it had once belonged to a famous artist).

Reached by an ancient wooden staircase, the place was less a Wyoming-sized SoHo loft than a garret with a pitched ceiling, odd corners, and no right angles. One can well imagine it as a secret hideout as well as the incubator for the “sticky black balls, pendulous sausages, and nets improbably stuffed with plastic bags,” with which, according to museum curator James Meyer, Hesse covered its scarred, pressed-tin walls.

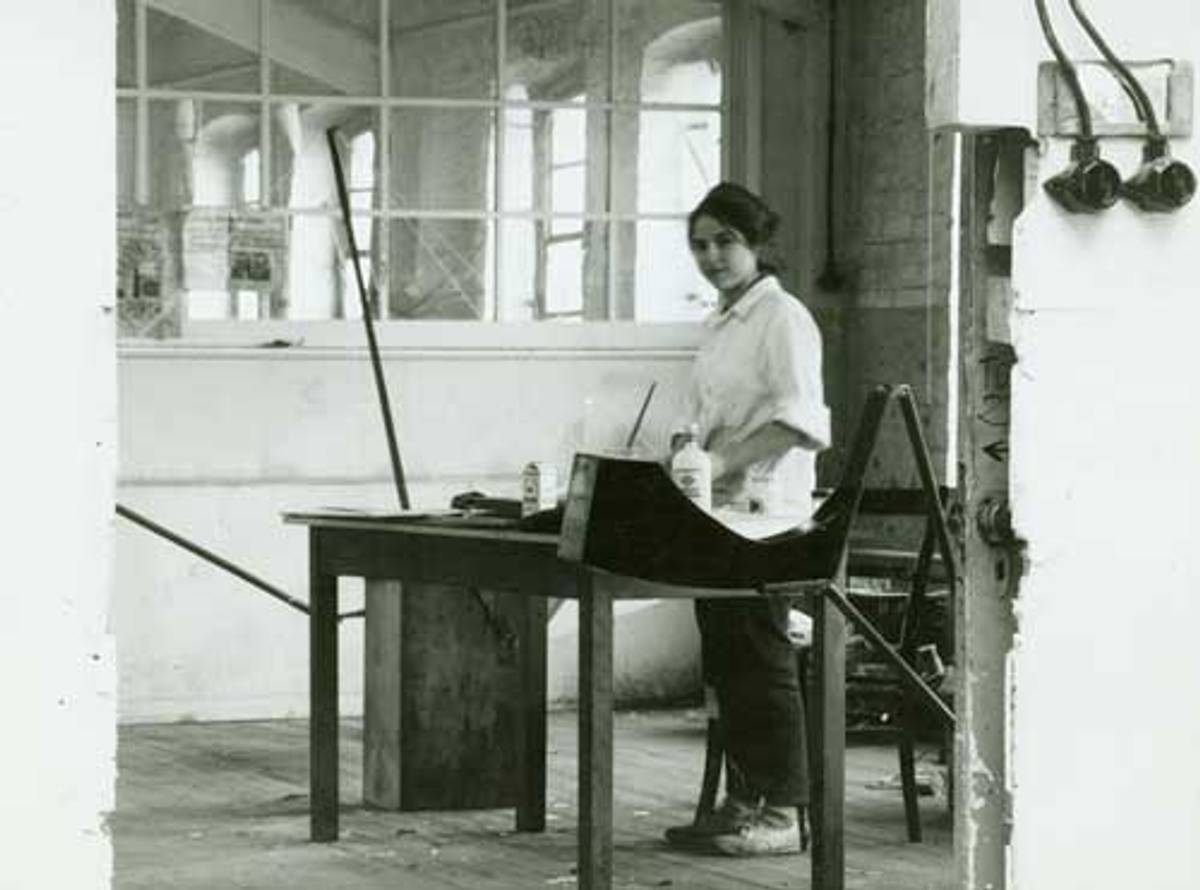

Begleiter holds off mention of Hesse’s background until the point at which, accompanying her husband, sculptor Tom Boyle, who had received a commission and a residency, she spent 15 months in West Germany—an experience that, however unsettling and, on occasion, traumatic, proved formative in her development. One might say that having returned to the scene of the crime, Hesse responded by weaponizing her art and effacing the distinction between painting and sculpture.

Picking up on detritus found in the former factory the couple used for a studio, Hesse turned from somewhat impacted abstract drawings to the making of three-dimensional objects too weird to be whimsical: “I’m patchke-ing around with new things,” Hesse wrote from Germany to a friend in New York. (Begleiter’s evocative portrait may leave you wishing to hear Hesse’s actual New York-inflected voice, which is furnished in the movie by the more polished Selma Blair, who also read a popular audio version of The Diary of Anne Frank.)

As eccentric as Hesse’s work was, it’s easy to imagine the male art world dismissing her “new things” as borderline kooky. Although art critic Harold Rosenberg seems never to have written on Hesse, her work was a splendid riff on what he called the “anxious object”—posing the question as to whether it was a masterpiece or an assemblage of junk.

However playful, inventive, and even, to use her word, “ridiculous,” Hesse’s work clearly has a darker side. The artist Robert Smithson, one of the first to describe her objects, deemed “Ishtar” to be “wonderfully dismal.” Intuiting that it might even be a sort of relic, Smithson added that “such ‘things’ seem destined for a funerary.” More recently, feminist art historian Anna Chave saw even “Contingent” as a “ghastly array of giant, soiled bandages or, worse yet, like so many flayed human skins.”

Hesse alluded to this morbid subtext herself, albeit indirectly. Asked by Nemser about her identification with other artists, she dutifully listed De Kooning, Gorky, Oldenburg, and Warhol, and then added: “I feel very close to [the minimalist sculpter] Carl Andre, I feel, let’s say, emotionally connected to his work. It does something to my insides. His metal plates were the concentration camp for me.”

It would seem the Holocaust was never far from Hesse’s thoughts. In a 1973 taped conversation with Nancy Holt and Lucy Lippard, part of Lippard’s research for her monograph on Hesse, Smithson recalled Hesse’s interest in Arko Metal Products, a SoHo-based shop that fabricated pieces for artists. “There were a lot of Jews basically who had been in concentration camps, and the whole atmosphere of the place was very, um …” Smithson says. “Very what?” Lippard asks. “You know, they had numbers on their arms, and it was a very gritty kind of place,” Smithson continues, adding that Hesse’s interest was reciprocated, he says. “I had a lot of pieces made there, and the Arko guy used to talk about her all the time.”

In the same taped discussion, Holt recalls Hesse’s attachment to the scrapbooks that her father made to document her childhood, both in Germany and New York. “I can’t remember a time when we were at her place that she didn’t bring out a memento of her past. … In a sense; she fed off of that material.” Boyle has said (although not in the documentary) that “the artist who influenced Eva the most was Adolf Hitler.”

Art critic Pamela M. Lee overstated the case when she complained that, “too often [Hesse’s] work itself is seen as little more than an epiphenomenon of the life—a life caricatured in terms of victimhood and neurosis.” Hesse’s accomplishments need no special pleading—she shook up categories, produced ambitious works charged with pathos and wit—but like Vincent Van Gogh or Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, or more to the point, fellow neurotic and alienated Jew Franz Kafka, her art cannot be separated from her biography. And like Kafka, Hesse kept diaries, about to be published in a near-900-page volume by Yale University Press.

A squarish cloth-bound soft-cover tome, Hesse’s Diaries is a book object as well as an anxious one (and a potential fetish for her admirers). Inspired by the example of Anne Frank, Hesse began keeping a journal in high school, although the extent material only dates back to her years at Cooper Union. While these fragmentary jottings do contain occasional thoughts on art, they are isolated islands in a stormy sea of adolescent self-doubt.

Hesse complains about her family, lists the novels she’s read (Exodus was inspiring) and movies seen (loved Jules and Jim), makes references to her therapy with dreams described and analyzed, addresses stern notes to herself, worries about her weight and height (she was short), and mainly obsesses over her boyfriends. Her 15 months in Germany, where she was thrown largely on herself and drafted long letters to friends in New York, make for the most compelling reading; the high-school confidential tone returns with a vengeance once she is back in New York and her marriage begins falling apart.

With fellow artists Sol LeWitt, Mel Bochner, Nancy Holt, and Robert Smithson, along with the critic Lucy Lippard, functioning as a de facto lunch-room clique, Hesse writes page after page on Tom Doyle, the sculptor she met and married in 1962, variously venting jealousy, rage, and remorse. The diary entries are additionally painful in that her mentor LeWitt, deeply in love with her, is suffering from her insistence that their relationship could only be platonic. To herself, Hesse invoked the incest taboo, claiming that LeWitt, the child of Polish Jewish immigrants, was too much like her father.

Doyle, of course, was not—although the hard-drinking Irish Catholic converted to Judaism to please Mr. Hesse. Even as her artistry matures and her career advances, Hesse remains erotically fixated on her estranged husband. Discussions of art are minimal. The diary does break off in early 1967, the year after Hesse’s father died and the year that she began showing widely and came into her own. One might hope that, in her last years (like Kafka in his), she found some sort of happiness or at least relief. The diary resumes briefly with her illness in 1970 to end more or less with a series of extraordinary passages written in the hospital only weeks before her death. She seems amazed by her absence of fear.

Toward the end of her life, Hesse was using polyester, fiberglass, latex, and rubberized fabric—material that may or may not have been toxic but had a definite life-span. In her interview with Nemser, the artist confessed to feeling “a little guilty” when collectors wanted to buy her work: “I’m not sure what my stand on lasting really is. Part of me feels that it’s superfluous, and if I need to use rubber that is more important.”

The art world had not yet been fully monetized; Hesse’s interest was more a matter of process than product. Begleiter’s movie picks up the next two sentences to give Hesse the poignant existential credo that serves as her last word. “Life doesn’t last; art doesn’t last. It doesn’t matter.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

J. Hoberman was the longtime Village Voice film critic. He is the author, co-author, or editor of 12 books, including Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds and, with Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting.