A Farewell to Armbands

I look back to the heady days of anything-goes postmodernism, when I was a rock star with a taste for fascist drag. Why did I do it?

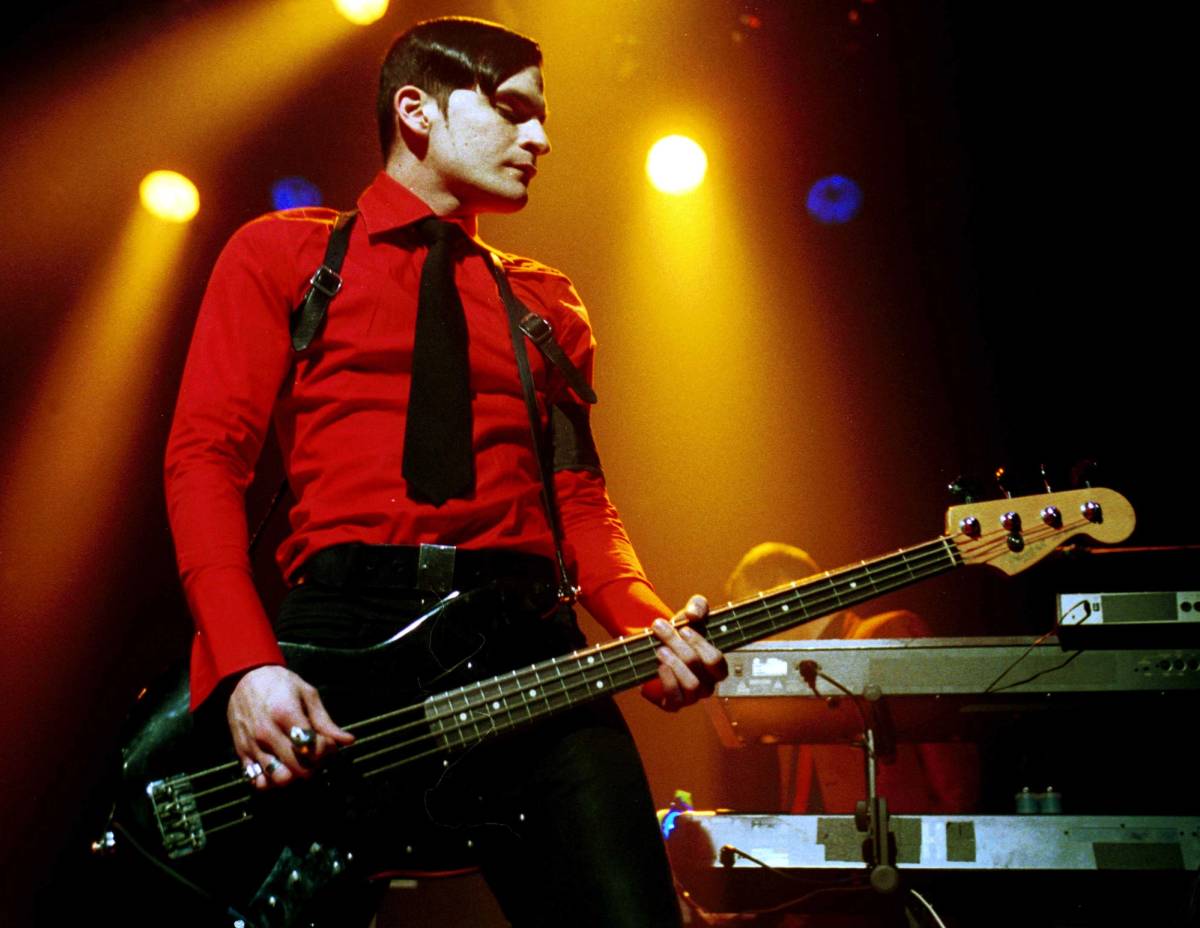

Sometime in 2004, the British pop music tabloid New Musical Express set aside a whole page in its table of contents to display a black-and-white photo of me looking straight at the camera in my usual performance outfit. “Why is Carlos from Interpol Dressing Like a Nazi?,” read the headline, a not untypical, barely disguised attempt to arouse a scandal. Interpol, a band you might have heard of, were conducting a new world tour to promote their second album. I was cofounder, bassist, and keyboardist of the band, and, much to the perennial glee of magazine editors, a flamboyant dresser. But never mind that the interview never once asked me about my stylistic choices. Weeklies like these were bought and sold on visuals and I supplied many. They paid their bills covering enfants terribles, “rock ’n’roll bad boys” with spectacles to share—though usually not of the fascistic sort.

I didn’t want to admit it, but NME’s coverage of my look, though obviously sensationalistic, was nevertheless apposite: I needed to be real with myself. Indeed, why was I doing it? Of all the dark looks I could’ve chosen, why did I pick a version so influenced by Nazi style?

Let’s start with the most notorious item I ever wore, the piece that captivated music and fashion lovers during my aughts-era limelight: the army-style holster. I was visiting my tailor one day when I first saw it draped over a black shirt on a mannequin. I noted its clean lines and militaristic sheen. A rush of dopamine, like I’d had my first shot of whiskey or snort of coke, rushed through my synapses, and I felt the palpable euphoria of artistic inspiration. Immediately the entire outfit crystallized: Under the holster a starchy monochrome button-down—along the sleeve would be pinned a pseudomilitary armband, through the collar a short, black tie—the ensemble would be weighted with a pair of black, 12-hole combat boots and on top of my head, a frozen sweep of hair combed in the Hitlerjugend style. It would be a jacketless affair connoting movement and mobilization—less high-class, ranked SS officer, more streetwise, brownshirt pamphleteer. Lurid images, scenes of conquest, flashes of lightbulbs danced through my mind.

Could this be kink, I thought, something close to the intended effect of S&M? I couldn’t be sure. I didn’t have much experience with S&M, though I was now feeling something close to a sexual charge. I was being acted upon by an illicit suggestion. Stretching the holster open and poking my hands through the armholes felt like putting on a brassiere, constraining but empowering. The hint of cross-dressing added another layer of intrigue.

Yes, I was beginning to mount a play. It would be the story of the Ambiguous Nazi, a familiar figure in the history of punk music. I was going to take it up in punk’s aftermath, in the context of Interpol’s success. I was feeling a little like The Wall’s Pink, the lonely hero who becomes a rockstar and then a demagogue. The shared monumentalism of the two arenas was perfectly spelled out in that movie. As the demagogue casts spells, so does the rockstar. Both insulate you from accountability. Everyone would see my play on the Jumbotron: How else to feel about it all other than optimistic?

The armband had no symbols on it. This would be a merely beautiful fascism—anonymous, decorative, neutral. The silver rings on my hands would nod to the roots in punk, not in history. The combat boots were modern. There was plenty here to establish this was drag, not reenactment. I was paying attention to lines, not to ideas. Pesky reminders, the events of history, the proof of the ugliness behind the beauty, were beside the point. I only wanted mood, not words. I would tell this story in silent panels, a comic strip with empty speech bubbles.

If you’d told me back then that I needed to answer for what my holster was saying, I would’ve said that it’s not “saying” anything, that it was apolitical and beautiful. To me this meant that it needed to be seen: How can something be beautiful if it isn’t observed? The galaxy of influences and references playing in my sensorium were from sexuality and subculture, not politics and history. There was the iconic punk band Joy Division (ironically named for the prostitution wing of a concentration camp). I recalled my time frequenting the Goth scene, where I once, or maybe even twice, saw someone wearing a rosary, a military armband, and a black, vinyl corset in the same outfit.

I smirked like a bad little boy when I thought of how Blixa Bargeld, the singer for the industrial noise group Einstürzende Neubauten, seemed to tease the punitive optics of the sex slave, with his tight leather onesie and large belt with a buckle that looked like a cock ring. The feel of the holster I wore registered this inversion of dom to sub: I’d picked it for how it signaled power, and yet–with the way it constrained me–I felt it tugging on me like a leash.

It was all a recitation, a voicing of the aesthetics of sensuality and the erotics of control, something Susan Sontag astutely captured in her critical description of S&M lifestyle in “Fascinating Fascism”: “The color is black, the material is leather, the seduction is beauty, the justification is honesty, the aim is ecstasy, the fantasy is death.” Had someone read those words to me at the time, I would have agreed, but followed it with a shrugging, Seinfeldian “Not that there’s anything wrong with that.”

But simple aesthetics only took me so far. Something strange was going on with my Nazi drag. I was a nihilist back then, and I definitely saw myself as a provocateur. But, where politics was concerned, I was as liberal as they came. The year was 2004; we were all too young for coded “alt-right” gestures.

And yet, somehow, the spell from Hitler’s day had, in fact, been cast over me, a half-German, half-Colombian boy from Elmhurst, Queens, who became a club kid and then a rockstar. I knew a lot of things that I’d conveniently managed to forget by the time I found the holster, family lore that had been imparted to me by my father when I was a child and remained hidden in a childish part of myself, even, or especially, when I got ready to perform in my stage-fascist regalia. Of course I hadn’t forgotten what my father had told me, I only stopped thinking about it, the way a lifelong thief knows exactly what they’re doing, but can’t bring themselves to connect their actions and their conscience.

The pieces of story that came to me of my father’s own childhood in Bavaria—a strange world full of Nazi salutes and panicked fleeing to bomb shelters—reached my ears while I sat on his lap, or while he held my hand on the street. I couldn’t help but compare the thought of my father as a boy throwing up his arm into the air in front of a swastika flag to my own experience holding my hand to my heart, pledging allegiance to Old Glory. His was an inverted benediction, from democracy to autocracy: He never commented on this inversion, this strange disconnect between our generations, and therefore the strangeness didn’t occur to me until much later in life.

He had his stories of growing up Nazi, of being primed for the Hitler Youth and the fateful intervention of Allied bombs upon all those would-be future Nazis. Once, during an air raid, the little boy began crying and this unnerved his father, who quickly handled the problem by smacking him in front of the rest of the nervous neighborhood, who were all cowering in the bunker and were likely relieved and grateful to the man who’d just found a way to release the tension they all felt. The morning after, my father went out with his friends to collect shrapnel from the rubble.

I might’ve heard these stories while sitting on the seesaw or while my wrists felt the warm grip of my father’s palms, my body flying in figure-eights in the air around his legs. I wasn’t yet old enough during any of this to be confused by the sweet ring in his voice, colliding as it did with the sour content of the images they described. I only knew I was flying like a bird, like other pairs of wrists attached to children’s bodies enjoying the thrill of these bouts of parentally assisted flight, even as these parents are not German and not so old that they could have seen what my father saw.

My father had experienced a dramatic upheaval at an impressionable age. The liberating American, with his can-do GI goodness (another “blond beast,” yes, though one with a cleaner line back to the rational Enlightenment), replaced the National Socialist image of the healthy Aryan male, familiar from Riefenstahl films. And my father fell in love with them. It was the sight of an American soldier shaking his leg to a jazz tune over his transistor radio out in the street that seemed to awaken my father out of the Nazi spell (“I’d never once in my life seen a human body move like that”). I guess it’s not that surprising to be so taken in by the invader when your country has been reduced to a scrap heap.

“You have no idea what it’s like to wake up one day, still a child, and look around and see all around you that level of destruction,” my father once told me, “to have everything you thought was true all of sudden fall apart and watch foreigners reconstruct it all before your own eyes.” He’d just come back from his mother’s funeral in Munich, a woman I never met. It had been decades since he’d visited his homeland. The Germany of the mid-’90s must have made an impression on him: he was able to experience what had happened to the land he grew up in, what the Marshall Plan had produced.

“Foreigners,” he said. I grew up as one of those foreigners, the Americans who’d come to liberate his country. But it was my father who I always saw as the foreigner, a Teuton married to a Latina, a man with a Kaiser Wilhelm mustache amid the feathered haircuts on the subway. And yet he saw himself as the quintessential American patriot. “I’m more American than Ronald Reagan,” a joke he loved to crack. He was full of contradictions—a Eurocentrist who wed a Colombian, a right-wing populist who read The New York Times cover to cover. He never could make a commitment to one side or another. His professed adoration notwithstanding, he never became an American citizen and remained content with his green card. Some invisible thing, a fishing line tethered him to the Vaterland, kept him from truly becoming the Yankee he desperately wanted to be.

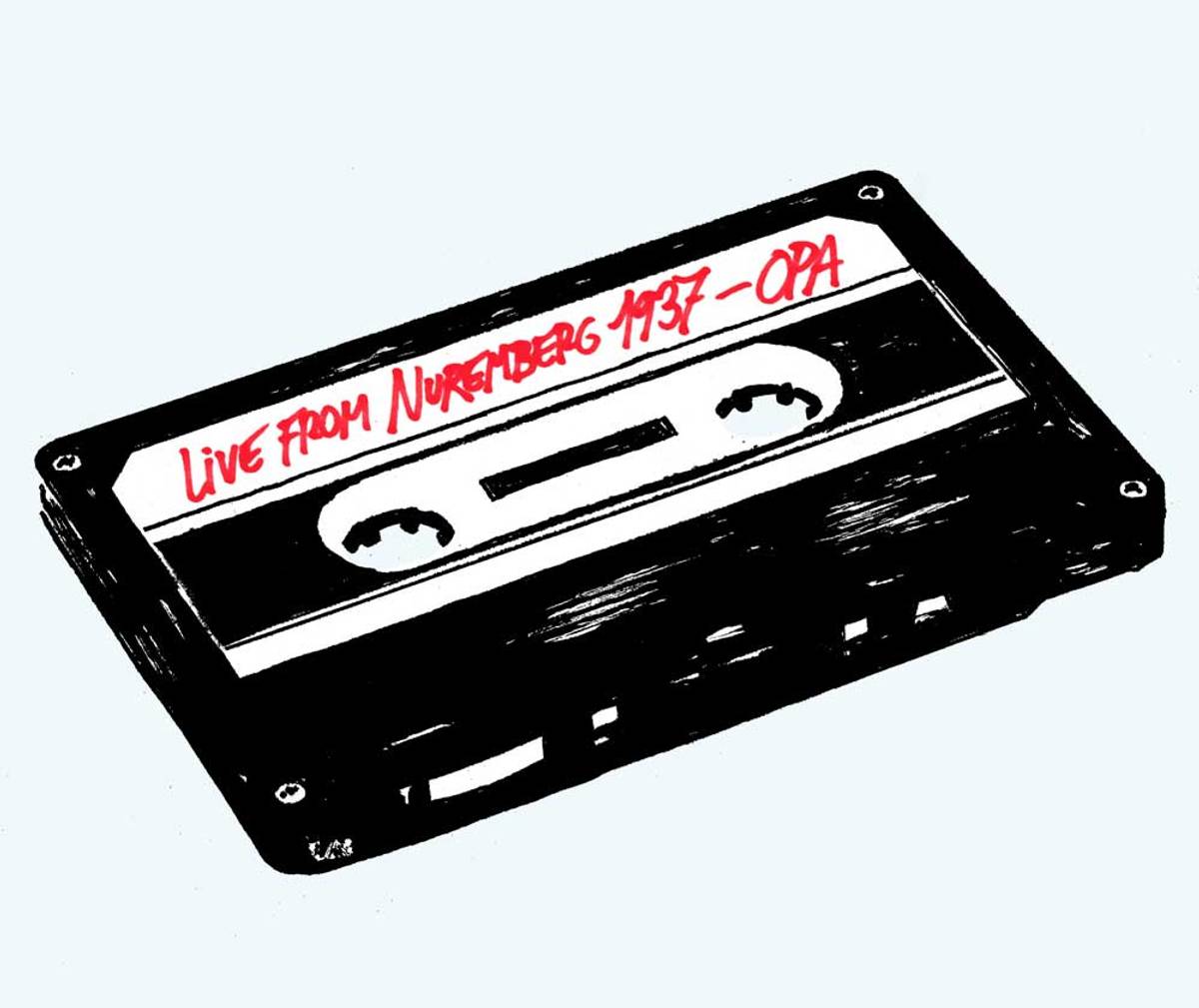

My father kept something hidden in a closet in the apartment I grew up in, a shoebox full of trinkets and paraphernalia. It contained a cassette that he must have made—not too long before I was born—from an old phonograph record. Every now and then, he would put it into the tape machine, the classic, rectangular affair with the built-in speaker familiar from ’70s movies. After healthy swigs from the bottle, my father would press play and I’d hear something I never heard outside of the apartment, something sublime, though I hate to admit it. It was the captivating sound of 1,000 men singing in unison, with the stomp of 2,000 boots hitting the ground in time, singing a foreign language, one I heard often on TV spoken by villains, all while watching my father, who now turned into one of those villains as he marched throughout the apartment, stomping awkwardly around the dinner table. He tried to keep his steps in time with the soldiers while adhering to his beloved native tongue like a credulous little boy who couldn’t get close enough to the sweeping phalanx.

A kind of elasticity would take over his muscles, a product of the liberating bottle. I was gleeful during these spells and I’d chase him around the table. When he saw me following him, he’d amplify his movements, almost goose-stepping, his cheeks rounding and his mouth widening. Which made me even happier.

Was this where my fascination with Nazi drag originated? Did it begin when I suspected that the kids in school might know about all this, when my bully started taunting me with accusations of Nazism because of my last name? When he found out about a pet name my father used for me, a delicate German nickname that translated poorly to English, he would yell it to me across the street—“Tsutsie!”—while Sieg Heiling. This was around the time that Tootsie came out, which seemed a cosmic affirmation: I was both a “sissy” and a Nazi! The S&M binary was already confirmed. My bully had, even at this early hour, put me in drag. But it also seemed like his predation was retributive, that somehow he knew what my father was doing to me with those tapes.

My father kept no tangible Nazi paraphernalia apart from the cassette. He balked at the swastika: It was a dead symbol, the American victory was decisive and, anyway he wanted nothing more than to be American. And yet, in our marching ritual around the dinner table, in his invocation of bodily movement and celebration, I was being imprinted with a secret initiatory rite from that very time, one that had taken possession of my father, as it once took possession of his father, and so many of his fellow ordinary Germans from 1922 until 1945. After his early childhood indoctrination, it persisted through him, undiminished or even strengthened by his wartime trauma, his later depression and alcoholism, and, yes, through his politics— and he had been unable to resist passing it down to me.

Was this why the old man wanted so much to put me in my place, to intimidate me, to scare me into submission, as soon as I literally outgrew him and let my hair hang to my shoulders? Was this why he made sure I heard the phrase “der Führer” spoken just a little too sweetly, why I started hearing talk of “Jewish propaganda,” of “Stalin killed more,” of “the genius of Goebbels”? The invisible line to his homeland was tugging, reminding him of his childhood, inducing him to up the ante in the face of the threat of my puberty.

The “damn longhairs with their civil rights” was just his cover story. The real one had everything to do with the contest between two eligible males. It wasn’t so much that now there was a disobedient hippie in need of discipline, as there was a new healthy body that was growing hair all over it. In Nazi Germany, this was seen as a glorious thing, with hopes for much javelin throwing in this body’s future and a christening through experience on the battlefield. But I wasn’t growing up in the blood and soil politics and culture my father grew up in: I was growing up in a liberalized world grappling with the full import of its democratic principles.

Scholars like Klaus Theweleit have documented how the Nazis depicted Jews and communists as effeminate sub-orders of humans corroding the healthy—and manly—body of Europa. It would take a homosocial fraternity, with its Germanic Männerbundof Teutonic war heroes, to meet the threat such feminized elements posed. The Nazi art that would later have such an effect on me buttressed this emphasis on neo-Hellenic vigor; symmetry and solidity register at the brain stem. It’s an art for social Darwinists, for believers in (manly) “might makes right.” I often questioned whether my father’s panicked recriminations against a boy who too closely started resembling the dirty hippie bugaboo weren’t first planted in that long ago time in the form of another type of völkisch outrage, that over “the dirty Jew.”

I’d become politicized. Already as a teenager, I was waging political combat in a space that was supposed to be my own home. At a time when a frightened boy was in need of stewardship, my father became another frightened boy, a vindictive sibling from another generation and another world, riding in on the backs of some horrifying, bloodthirsty wolves.

His posture shifted, he somehow became taller. The angle made him seem monumental. I remember the show trials of my adolescence as though I were in a German expressionist film, with my father bathed in a harsh spotlight that made him look broad-chested, more the square-jawed Mussolini than the littler Hitler. Through some psychic trick, he became a terrifying minister behind a lectern—distorted, stretched, elongated, like a figure on an art deco frieze.

It’s the hallmark of the demagogue to make the charges opaque but the judgment clear. I never really knew what he wanted from me. I remember begging him through tears streaming down my face sitting across the dinner table to clear up the confusion, so we could come to an understanding, so he could stop the persecution. Yet, even at that terrible moment, I still could not tell what he wanted.

Though I knew full well what he didn’t want. From time to time he’d get on his soapbox to denounce me in front of my mother and my brother and proclaim how the family (Germany) was a body and how that body was diseased (as Germany had been diseased), and how to save it from the disease was to eliminate the viruses that plagued it. My younger brother was referred to as an imperiled “innocent lamb” in imminent danger of becoming corrupted. My father would shame my mother for not agreeing with him, saying that the parents needed to “speak with one voice” in order to banish this problem and keep it from spreading. The invisible line back to the Nazi homeland was tugging wildly.

Something about my father’s cruelty toward me felt pre-programmed and not under his control. Lingering scripts animated the old man’s smears, traces perhaps from the disapproval my grandfather had directed at his own son decades earlier. “I come from peasant stock,” my father liked to say, and there was always a mixture of pride and shame in the testimony. Indeed, Opa Dengler was a “man’s man,” “Nazi classic,” in fact. He died before I was born and I never even saw a picture of him, but I imagine him from my father’s telling as coming close to the streetwise and thuggish SA, with their beer hall brawls. It was never easy getting facts about this mysterious figure who surfaced only when my father wanted to cull sympathy for how he was treated. “He was a truck driver,” he’d like to say whenever as a boy I would ask him for information, “he liked to come home drunk and beat my mother and he often smacked me around, as well.” It must have been hard for my father.

Opa Dengler was, in fact, a Nazi, in the official sense. Once the Nazis took power, while my father’s family lived in the small Bavarian town of Plattling, Opa became a chauffeur for high-ranking NSDAP officials, the personal driver for a handful of them all over the country. Legend had it as I was growing up that Opa had even driven “der Führer” himself on several occasions. I imagine he had to have enrolled in the party in order to keep this cushy gig, which gave him a high degree of prestige. He must’ve looked gigantic to my father, an only child, overprotected by his mother, a woman who noticed the young boy’s intellect and encouraged him to read instead of driving cars like his dad.

Oma’s influence set my father down the path toward self-education: He has a natural intellect, he’s gifted with analytical smarts, as Oma herself was. I didn’t grow up around books, my parents weren’t the biggest readers. Still, I give my father credit for my own autodidactic streak. The Nazis hated folks like my father, the nerdy, quiet types. They preferred the hypermasculinized ideal which my truck driving grandfather epitomized, something my father could never achieve.

Oma Dengler must’ve loved seeing her husband in his uniform. Perhaps my father did, too. How compelling such deliberately crafted spectacles must have seemed to such a young boy. Soon, they would never see it again: Opa buried his uniform when he learned of the Allied advances.

In any case, my father was too complicated to follow in Opa’s footsteps. He wasn’t made for the manly, Nazi working class. He was better cut out for liberalism and education. He’d hoped he could find those things in America, away from the rubble and his parents. But he didn’t find them.

Maybe the invisible line that was tugging at him all those years was reminding him not only of the failed state of the Deutsches Reich, which he’d been mysteriously instructed to uphold, but the underlying reality that, at least according to the insane standards of all of those “particles of Hitler” that had coalesced into the National Socialist death machine, he too was a failed state.

Had I been trying to compensate for my father’s perceived failures at masculinity? Was my Nazi drag the result of an unconscious alliance with my Nazi grandfather, a puerile gambit at fixing the “feminization” in my lineage? These were the questions that would have to wait for my awakening, a moment I experienced in my father’s presence. I had showed him the picture of me in the NME, with the headline. It must’ve seemed like bragging to him, or a violation of our family code that kept acknowledgement of the Nazi past strictly in house. Look at what they’re saying about me! About us?

He was speechless, less—I think—from shock than from puzzlement. Maybe nerves, too, seeing how I was giving away a shameful family secret. It could have also been guilt. I know that he feels pain about his failings as a father. Maybe he was dismayed to the point of recognition. I won’t ever know. Though our relationship has improved dramatically over the years, the bar has always been set pretty low, so, at the end of the day, we don’t talk very much or very deeply.

I first began to notice an inkling of the truth during that quiet hesitation with my father, that it was in fact no coincidence that my moonlighting as an artsy brownshirt came on the heels of my grandfather’s stint as somewhat the genuine article.

No matter how much I wished to coat my choices with postmodern performative gloss, the grandson of an actual Nazi was dressing like a Nazi.

No matter how much I wished to coat my choices with postmodern performative gloss, the grandson of an actual Nazi was dressing like a Nazi. I had, through some mysterious logic, disinterred the uniform my grandfather had buried and “performed” it in front of a public itself eager for this type of resurrection of Nazi spectacle. This was no punk-situationist prank. It was a leakage of history into the present, a blob moving through time, seeping into my synapses, animating my creative process with an unseen push from long before. Maybe then I finally felt how conspicuous this decision had in fact always felt to me, how it had been living there just under the skin of my awareness. No matter how cool it had felt to me to play the villain, a blithe assumption of the innocence of aesthetics, of “art for art’s sake,” was beginning its long implosive course.

Those disgraced symbols fit a little too snugly. I could not lay claim to the punk rocker’s prerogative. Being famous could not insulate me, either. This playacting was a proxy, a placeholder made all the more effective by the attention it received as it stood in for the original of a boy chasing his father round a dinner table while the recorded sounds of actual Nazis marching and singing played in the background. The grotesquerie of that image is hard to bear, even now as I write. I see my art infiltrated, a violation of its sacred precincts. Here was the limit to provocation. Being a rockstar couldn’t save me anymore, couldn’t absolve me from owning up to this horrible lineage.

But Nazi cosplay wasn’t just my shame: It was also my redemption. I was guided to sidle up to the horrible so that I could better understand the horrible that lurked in our family’s collective unconscious. The artist can be an autocrat, hellbent on ultimate control. And though the S&M binary implied in my Nazi cosplay was my most efficient means of achieving total control of the artistic product, in its unconscious reenactment of the biopolitics of my father’s abuse, it also tried to achieve total control over the suffering I’d experienced.

The sexualized Nazi, familiar from films like Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter, was the carapace behind which I could enact these scripts of suffering, the seesaw between the sadistic and the masochistic that makes BDSM so thrilling, a thrill which the Nazis themselves, with their elevation of pubescence as the terminus of masculine development, would have understood well. The script of S&M, in compressing sexuality to a coarse binary, is a natural fit for the coarse Nazi.

My father had taught me how to reenact, how to put up a play. In equating the family to an organism and, by implication, my own body as a virus plaguing that organism, my father was enacting these very scripts of total control, the surveillance and exploitation of the human biome inlaid in the National Socialist project, which had been enacted all around him growing up in Nazi Germany. And in my artistry I too always sought to play and also to put up a play.

I had to mock up my inner world in Nazi drag so that one day I might tell the deeper story for which I hadn’t yet any words. It was only through playacting the sadist that I could hope to one day listen to the dreams of the masochist, my inner sufferer, whose misery at the hands of the original sadist, my father, was cloaked in silence, but whose story I could now finally begin to tell.

The words for these events would escape me for a while longer. I spent the better part of an adult life throwing objects and making loud noises, silently believing that I was such a noxious, infectious presence that no one close to me could trust me. It always seemed my rage was too white hot for my vocal cords, that they’d singe under the extreme heat. I could never speak of what he’d done, of what had been shown to me, not because I had hidden the events from consciousness, but because it felt as though my body would break in two if I tried to express the horror and helplessness of his psychological crimes against himself and against his son. The holster was the first silent beat of the ensuing script. Now Act 2 has put text into the speech bubbles.

It’s easy to imagine stories about the brilliance of style decisions becoming stories that condemn those same decisions on purported moral grounds, seemingly from one year to the next. Nonetheless, I still insist on the promise of drag. I believe that the elevation of an aesthetic to the level of camp can neutralize its original sincerity, its original content. This type of recontextualization, of course, is not specific to drag as an art form. It was exactly what the punks were after in their own use of fascist signifiers and other taboos. If it’s true that such neutralization occurs, I can take solace in knowing that somewhere behind my conscious intentions in the moment, my redeployment of Nazi regalia as a form of drag was, in its own mute way, a disavowal of the disturbing family legacy from Germany. I was using camp as a kind of hot lamp, bringing light and burning away residues, cauterizing wounds that had been left open.

At the end of a long tour I left the holster in the lounge of the tour bus by accident. It might’ve made it all the way to the depot where maybe it sat until the next band rented the bus and went on the road. In all likelihood, the driver, cleaning up the vehicle for the next tour, tossed it or kept it. I used to regret not being more organized—not making sure to have had the forethought to hold on to this artifact from a different time. Who knows, maybe one day they’d put it in a rock music museum of some sort? Or I would have it today and would keep it stashed safely in some shoebox in the closet. I would go to it now and then, as I would a photo album from high school days, and reminisce with friends and family about the way things used to be. Maybe I’d show it to my kids.

But it’s been a long time since I’ve had that thought.

Carlos Dengler is an actor, writer, composer and multi-instrumentalist. He co-founded the rock group Interpol in 1997 and played bass guitar and keyboards with them until 2010.