A Find Unlocks Comics Mystery

A drawing by an American, discovered in a Jerusalem junk shop, reveals German Jewry’s lost grandeur

“We buy junk, we sell antiques.”

The kind of store that features a sign like this has long attracted me and my partner in research and family, Isabella Ginor, avid collectors of objects whose hidden stories grant us hours of enlightening investigation. Jerusalem, our hometown, has long been a fertile milieu for this hobby, but its golden age may be approaching an end. The second-hand dealers are clearing the homes of the very last Yekkes—the German and Austrian Jews whose influx into Palestine during the 1930s brought an abundance of Mitteleuropa culture and its artifacts.

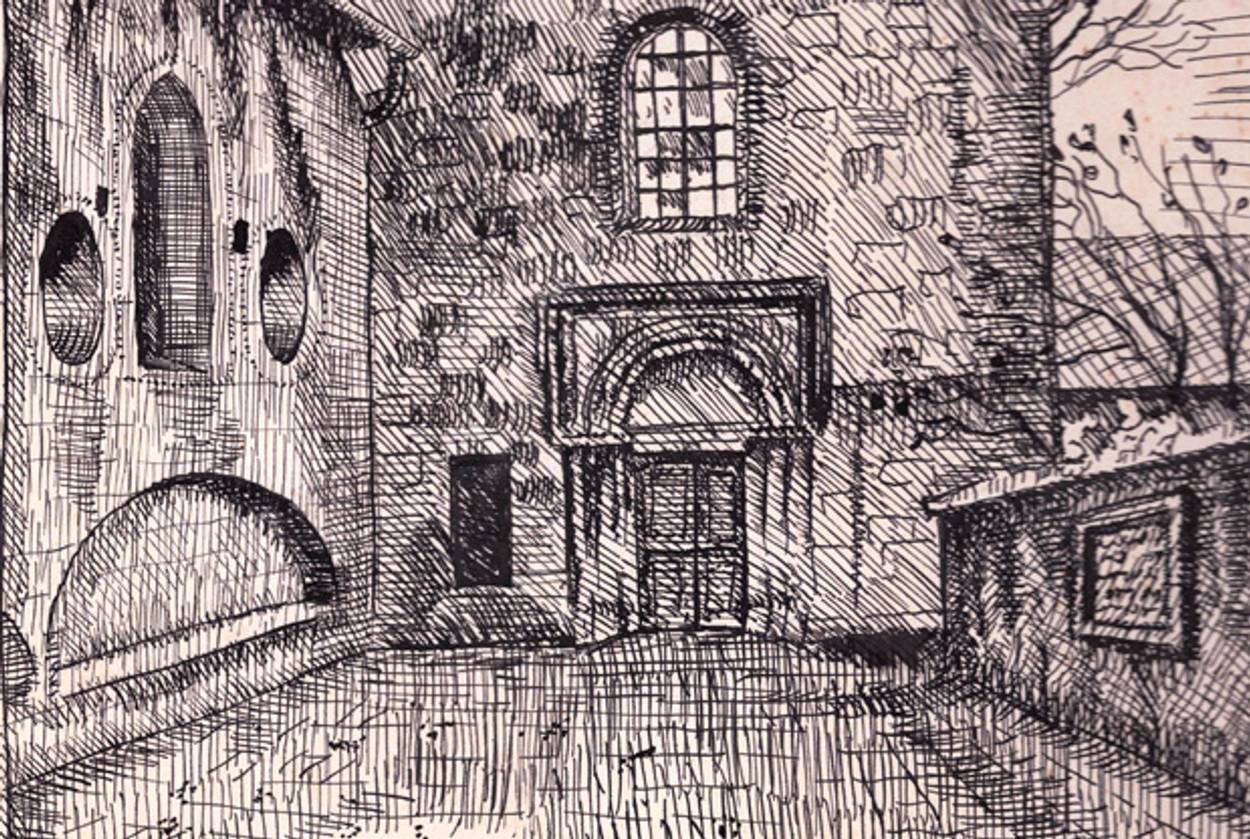

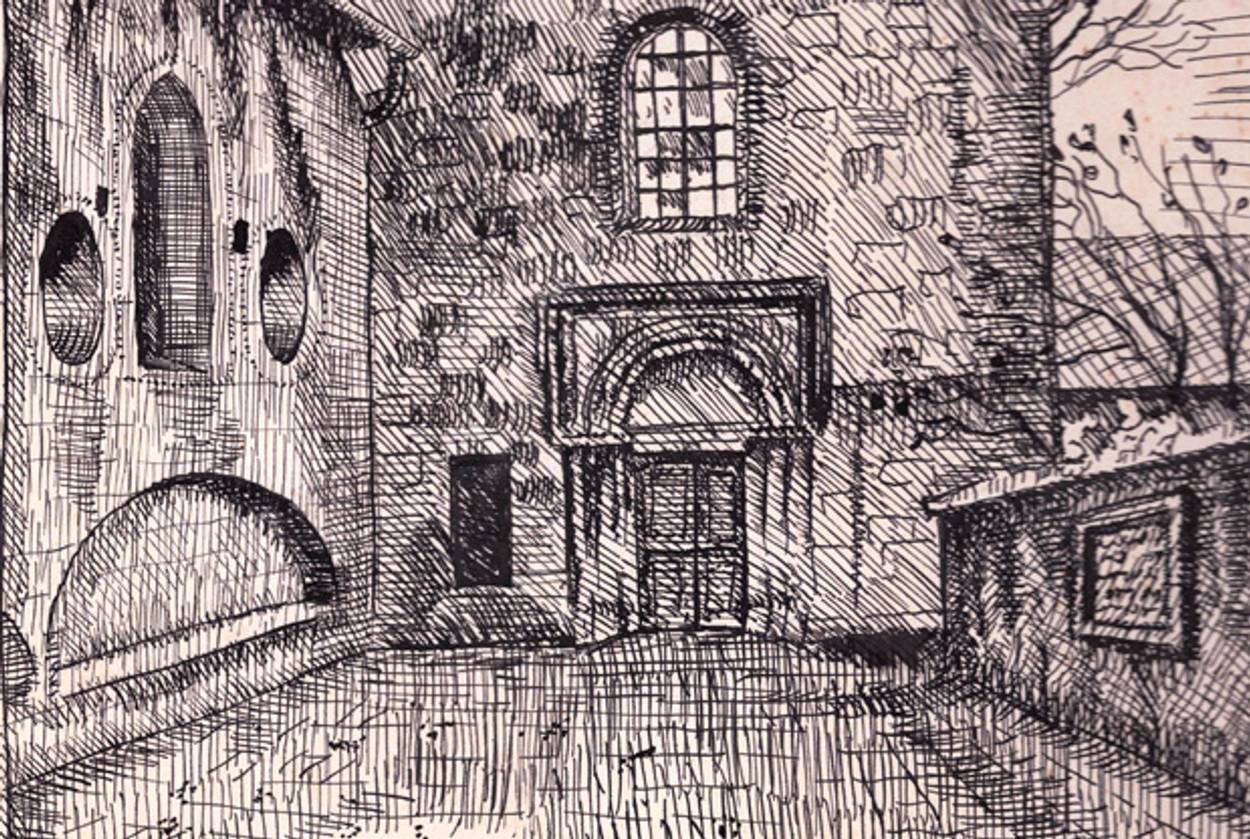

This summer, from the dusty floor of such a store, I picked up a small picture in a prewar-vintage frame. After wiping it off, we saw a pen-and-ink drawing. It showed, in near-architectural precision and detail, an old stone building with a gabled roof and arched Romanesque portal that looked vaguely familiar.

The signature was very clear: “Paul Reinmann, 33.” But Isabella’s sharper eyesight also made out a faint pencil inscription: “Synagoge zu Worms.” My schoolboy memories came flooding back. “That’s Worms in Germany, one of the oldest Ashkenazi communities,” I said. “And this must be the medieval Rashi Synagogue. Wasn’t it destroyed by the Nazis?”

If I showed any hesitation, Isabella overruled it: “So this is a piece of heritage, and we have to rescue it.” We paid the $5 asking price and hurried home to learn more—first of all, who this Paul Reinmann was. His work looked better than a gifted amateur’s, but neither of us had ever heard his name.

A quick search online produced thousands of hits and hundreds of images. Nearly all of them involved American comic books. A Paul Reinman—single “n”—was from 1940 a stalwart of the industry, best known as a regular “inker” for some of the legendary artists in its “Silver Age” such as Jack Kirby (Kurtzberg), as well as Joe Kubert. That is, Reinman filled in the detail for the printed versions of Kirby’s penciled sketches, which earned him too a niche in the comics pantheon. He also penciled less-known comics of his own.

“Pencilers” get most of the vast comics literature’s attention. Like vice presidents, inkers rarely get more than footnotes, and virtually nothing had been published about Reinman’s persona. The only detail we found about his early biography was his birthdate in Germany: Sept. 2, 1910. But could this be the same person? Where we found a signature, it was in comics-style block letters rather than in our drawing’s longhand.

I’ve never been much of a comics aficionado. In 1950s Tel Aviv, before English instruction began in sixth grade, I scored great success translating Little Lulu and Dennis the Menace for my classmates. My source was the colored Sunday funnies that my beloved Aunt Evelyn faithfully clipped and sent from New York. But that’s about as far as I got, and the superhero or horror genres that became the industry’s core—and that provided Reinman with his bread and butter—never appealed to me.

So, with guidance from Tom Kraft, Isabella and I contacted some actual authorities in the field, who were just as intrigued by this mystery. First, comics maven Jim Amash confirmed that some of Reinman’s first strips did bear a matching script signature. “So,” he asserted, “you have the right man.” Then Rand Hoppe, the curator of the Kirby Museum, helped us to enlist researcher Alex Jay, who made our day by establishing that on arrival in the States, Reinman still spelled his surname with a double “n”—and gave Worms as his birthplace.

From this start we gradually discovered how the 23-year-old Paul Reinman and his drawing’s subject encapsulate the lost grandeur of German Jewry, as well as its survivors’ cultural contribution in America and elsewhere.

***

Worms and its neighboring Rhineland cities of Mainz and Speyer were the cradle of Ashkenazic Jewry and the centers of its scholarship, in the first millennium C.E. It was at a gathering in Worms, around the year 1000, that Rabbenu Gershom of Mainz proclaimed his epochal bans—one on polygamy and the other on divorcing a woman against her will. On both, he may well have been responding to Worms’ formidable ladies: When over the following decades a synagogue was built for the community’s men, it was followed by an adjoining one for women—the first of its kind. It faced the ark at a right angle to the men’s synagogue, and at the same distance. A female shlichat tzibur standing at an aperture in the partition between the halls would lead her companions in prayer, a notably progressive practice for its time. There were qualified candidates for this role among medieval Worms’ learned Jewish women, as a present-day counterpart, Rabbi Elisa Klapheck of the Egalitarian Minyan of Frankfurt, described in a lecture at the site this Sukkot.

The region’s Christian rulers and populace were less enlightened. During the Crusades and on recurring occasions afterward, such as the Black Death, the Rhineland Jewish communities suffered unspeakably bloody pogroms and expulsions that were lamented in generations of literature (including the last verse of the Hanukkah hymn Ma’oz Tzur). The synagogue that Reinman drew incorporated the foundations of one that was begun in 1034—which made it the oldest in Europe still occupying the same site—but was destroyed soon after. It took on the shape that he depicted around 1175: old enough to breed legends, which also feature women.

The wall on the left of Reinman’s drawing is the exterior of the “women’s synagogue.” On the outside of its opposite wall, a shallow rounded niche in the masonry was for centuries pointed out as the site of a miracle. A pregnant Jewish woman was almost run down by crusader horsemen (or the local nobleman’s—or bishop’s—own carriage; versions vary). The narrow alley afforded her no escape, but when humans showed no mercy, the stones did and gave way to accommodate her. So, it was said, Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaqi (Rashi) was safely born two days later, to become the greatest Bible and Talmud commentator.

This version at least is apocryphal; the “women’s synagogue” was built after Rashi’s time, and he was born in Troyes, France. But he did come to Worms to study at its renowned yeshiva, became its best-known graduate and teacher, and the synagogue’s semicircular study hall (its roof is visible above the wall on the drawing’s right side) was named for him, among other landmarks. The miracle, which was originally attributed to the mother of the earlier sage Rabbi Yehudah the Pious (he-Hasid), was gradually transferred to his illustrious successor’s.

The modern Hebrew poet Saul Tschernichowsky focused on the terrified mother rather than her unborn child when he adapted the folktale for one of his best-known ballads, The Wonder-Wall of Worms. Tschernichowsky had studied medicine at nearby Heidelberg (together with the subject of my and Isabella’s previous Tablet article, Dr. Max Eitingon) around the turn of the 20th century. But by the time he wrote the poem in 1924, its final stanzas were a prophecy soon to be fulfilled (my translation):

Thus was it in those days of yore

When evil bathed the town in gore

And human beasts did reign.

When arrant villains held their sway…

But had this happened in our day

Not even stones would budge.

So, Reinman could hardly have chosen a subject more evocative of German Jewry’s past—and its impending fate. The ancient Jewish cemetery, Heilige Sand (Holy Ground), in the shadow of the city’s Gothic cathedral, was already rather derelict. Martin Buber (whose forebears also hailed from Worms) described a visit there in a famous disputation with a Christian cleric in January 1933: “Death has befallen me … but the covenant has not been revoked. I’m lying on the ground, tumbled like these tombstones. But I have not been rejected.” Buber was referring to the covenant with God, but the attempt of many Jews to forge a covenant with their country as “Germans of Mosaic faith” was rejected within weeks after he spoke, when Hitler took power.

The Worms congregation had long since been split on its religious observance: As emancipated Reform progressed in the mid 19th century, a church-style organ was installed in the synagogue (to be played by Christians on Shabbat). In 1842, the partition between the men’s and women’s sections was removed entirely. Samuel Adler, the son of a Worms rabbi, led prayers there in German rather than Hebrew—a practice he continued as rabbi of New York’s Temple Emanu-El. Those of Worms’ Orthodox worshippers whose sensibilities were offended set up a separate synagogue nearby, so that Rashi’s was now called the Old Synagogue, Alte Synagoge or Schul.

All Jews, however, were compelled by the Nazis to wear the yellow badge—reviving a medieval decree that required the Jews of Worms to display a yellow cloth in their garb. Then, on Kristallnacht, 74 years ago Friday, the Worms Schul was one of over 1,000 synagogues that were sacked and burned. Reinman’s sketch is then probably the last artist’s impression ever made of the venerated shrine.

It might have made a neater story if we were able to connect Reinman’s German past with his American career, but we can’t—or at least not conclusively. Expert opinion holds that “Holocaust comics” (an oxymoron if I ever heard one) was a much later phenomenon. Although the comics industry was heavily Jewish, Marvel Comics—where Reinman did his best-known work—even came out with a completely unrelated character named “Holocaust.” But there were next to no genuine Shoah topics before Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking Maus first appeared in 1972, when Reinman’s career was approaching its end. Comics scholar Michael Vassallo searched his vast collection and found only one exception with art attributed to Reinman. These two rather crude pages in a 1952 Atrocity Story tend to prove the rule: The Holocaust is presented as a prelude to “Red” war crimes in Korea, and the Jewish identity of most victims is never mentioned.

This does seem to be a generational matter: Spiegelman stressed his identity as the son of survivors; Reinman was almost one himself. He also penciled a story about a Serbian anti-Nazi guerrilla leader, but though one can hardly believe that his post-1933 Jewish experience left no mark on his psyche, overall he appears to have been one of his many contemporaries who suppressed the trauma. Likewise, I’d beware reading too much into his work on Bible Tales for Young Folk, a short-lived and Christian-oriented series in the early ’50s. In most cases, the artists didn’t originate the titles, plots, and texts anyway.

Also quite typically, Reinman appears to have been reticent if not reclusive overall. There are only a handful of grainy photos of the artist—the best appears here thanks to Bill Hillman of ERBzine.com—and a single known press interview, given at age 67 to the Palm Beach Post (and also located for us by Hoppe). Either Reinman mentioned his background only in passing, or the reporter cut any detail (and referred, erroneously, to “Hitler’s rise to power in the late 1930’s”).

***

That reporter also missed a better story: Reinman may have drawn imaginary superheroes, but he was a modest hero himself. A database of Worms Jews, painstakingly assembled by the city’s archive, shows that Joseph Paul Reinmann was the second of five children (and the oldest son) of a real-estate agent and farm-produce broker who lived in the Worms suburb of Pfiffligheim from 1908. He told the Florida interviewer that he began to draw at age 3. In a bio that he provided in 1961 for a typewritten Tarzan comics fan newsletter (unearthed by Vassallo), Reinman recalled that “before I went to school, I must have shown quite an interest and skill in drawing, because … my grandfather always bought crayons and paper for my artistic efforts.” His formal education was limited to high school, with little artistic training or none; then “I succeeded in getting a job in a department store as an apprentice for sign painting and show card writing.” By age 22 he had moved 200 miles away, for “commercial employment” in Germany’s industrial heartland. “I worked for many leading stores as a fashion artist and designer of window displays.” Reinman omitted any mention of his subsequent history until coming to America in 1934.

But the database shows that at the end of May 1933, after Jews in Worms were assaulted and their stores boycotted, Reinman returned home. This is when he drew “our” picture of the Old Synagogue. The choice of subject was hardly coincidental: In what would be German Jewry’s last hurrah, the Worms Jewish community was preparing to mark the shrine’s 900th anniversary on June 3, 1934. A contemporary of his parents would recall: “Prominent men and women came from far and near to be our guests. … It was a dignified but sober celebration. This was no occasion for rejoicing any more, for the coming events already cast their shadow.” Nearly all the city’s 1,000-odd Jews attended the ceremony, but no representative of the civic authorities did.

Among the many Jewish dignitaries, the rising young rabbi and anti-Nazi activist Joachim Prinz exhorted “all Jews living in Germany to lay plans for an unprecedented act, mass emigration. I do not know how many heeded my words or had already decided to leave without my prompting.” Paul Reinmann was among the latter, whether or not he was present at the ceremony: On June 15 he stepped off a steamer in New York. Reading between the lines of the names and dates, it’s obvious that with commendable foresight, Reinman had either resolved on his own or was tasked by his parents to get the family out of Hitler’s reach.

The young immigrant entered his occupation as “painter/commercial artist.” He gave his “destination” as his aunt Johanna, who had arrived in the United States around 1890 as a girl; by 1934 she was widowed. She presumably gave Reinman the essential sponsorship for immigration, as she had for his cousin Willi in 1927.

In his 1988 interview, Reinman described a relatively easy and fortunate entry into comics: First he secured a “commercial art” position with a mail-order company, but when it moved to Chicago, he preferred to stay in his folks’ prospective port of entry. “I walked into MJL Comics (now Archie Comics) and found a job.”

Seventeen years earlier, he related a much more difficult course. “My first job was as assistant to a designer of neon signs. Then the going got tough and I took any kind of job just to make ends meet, and I worked in the check room of an exclusive men’s club on New York’s East side … but luckily I had a chance to get back to art and I took a job in a studio of a match factory. Here I did designs of match covers and lettering. A few years later I quit and started to freelance in posters, fashion drawings, and package designs. Then I brushed up on my drawing technique and practiced illustration in many mediums. I succeeded in getting assignments for dry brush drawings for pulp mags, and following this I broke into Comic Book Cartooning.”

The volume of Reinman’s known output, when he began to get credits in 1940, was prodigious; before then, he must have worked even harder not only for his own upkeep but to save for his family’s passage and resettlement. Within four years, he brought over his parents Bernhard and Anna, all his siblings, and the latters’ spouses. His younger brother Friedrich and sister Emmy joined him in 1936; their parents in 1937 (along with Willi’s brother Ludwig, also an artist); older sister Alice in March 1938. By the time of Kristallnacht that November, only Hans remained.

In Worms, the synagogue was actually targeted only on the morning of Nov. 10, after a night of rampage against Jews and their homes and businesses. The rabbi noticed a fire and managed with some colleagues to put it out. But the arsonists returned with police protection and overcame the vice-principal of the Jewish school, Herta Mansbacher, who tried in vain to block them with her body; no stone moved to shelter her, and no firemen came to fight the blaze. The synagogue was left gutted and roofless and its community subjected to intensifying persecution. With war and calamity looming, Hans married in February 1939 and managed to get out to England with his bride. Willi’s parents, Max and Flora Reinmann, and their daughter Elsa were still awaiting a U.S. visa in 1940. By then it was too late. They had already lost their home and wine-trading business and were subsisting on “remissions from family abroad” and sale of their furniture—and worse was to come.

Hans’ subsequent travails illustrate the difficulties Paul faced in getting his family not only out, but in. Hans was interned by the British as a national of a hostile power, shipped to a detention camp in Australia, and then made his way through India to Palestine. (Could he have been carrying Paul’s drawing through this odyssey, and left it in Jerusalem? We doubt it.) He was reunited with his wife in the United States only in November 1945. Paul had completed his self-assigned mission. In September 1938, he married Dora, two years his junior, a native of Reichelsheim, not far from Worms—whom perhaps he had also helped bring to America. His later comics collaborator Joe Sinnott recalled, and Paul mentioned in his 1961 bio, that the Reinmans had a daughter who was then 17. But neither of them provided her name, and we have not yet been able to locate her. (If she reads this, please contact us by commenting or emailing [email protected].)

In 1942, the Nazis had to use heavy hydraulic equipment when they came to tear down the synagogue’s “mighty walls,” as recorded by the son of the city archivist at the time, Friedrich Illert. His father’s pleas of “museum value” had succeeded in preserving some of the synagogue’s artifacts, including the scorched Torah scrolls, but not even a remnant of the edifice. “Soon grass and weeds grew over the ruins, and the children played there.” Not Jewish children: By then the 400 Jews who remained in Worms had been crammed into a few houses around the Schul and then “transported” to the east for extermination.

***

Eighteen years after Wonder-Wall, Tschernichowsky, by now in Palestine, again evoked medieval Worms in a cycle of ballads. One, The Nameless Candles, describes memorial flames that used to be lit in the Old Synagogue for the souls of two mysterious strangers who gave their lives to save the entire congregation from death for alleged blasphemy. Martyrdom, he wrote, was still stalking the Jews:

By fiery death or water, by arrow or the axe,

Two thousand years ago, tomorrow—or today, perhaps?

The poem is dated March 17, 1942. Three days later, Willi’s sister Elsa, 39, who had already been subjected to slave labor, was deported to Nazi-occupied Poland, in the same transport as the heroic Herta Mansbacher. Both were gassed at Belzec. Elsa’s parents, Max and Flora, as well as Paul’s Aunt Emma, were shipped that September to Theresienstadt among the last of the city’s Jews; Max perished there, and the two women at Auschwitz.

Much of Worms was devastated by Allied bombings in February-March 1945, but some buildings of the old Judengasse—including the Orthodox Levy Synagogue, which had been spared on Kristallnacht because it adjoined “Aryan” houses—remained standing around the field of rubble that was the Alte Schul. In 1959, the city of Worms initiated the reconstruction of the Old Synagogue at the behest of, among others, the archivist Illert. But almost no Jews had returned, and there was some opposition to the idea in Jewish circles. They gradually warmed, and the restored Schul was rededicated—fittingly—on the first night of Hanukkah, December 1961 to the strains of Ma’oz Tzur.

Comparison with Reinman’s 1933 drawing shows that the restoration was remarkably accurate. The vaulted men’s synagogue is occasionally prayed in by men and women together, from the community of Mainz and by Jewish servicemen and women from nearby NATO bases; the former women’s synagogue is a venue for cultural events such as Rabbi Klapheck’s presentation. Hate has not vanished: As recently as May 2010, the restored synagogue was torched again in an apparent pro-Palestinian attack. But this time the firemen did their duty, there was no serious damage, and Germany’s leaders were united in condemnation.

It doesn’t seem that Reinman attended the rededication ceremony, though he probably at least heard about it. This was the year he wrote his own life story for the Tarzan fanzine; he was approaching the height of his comics career and doing well enough to play tennis and engage in carpentry as a hobby. But he did comply when 15 years later he was contacted by the database compilers from Worms. He contributed a letter, as did his brother Hans (now John) and Alex Leopold, Alice’s husband, which provided the timeline of their story. Margit Rinker-Olbrisch of the Worms city archive sent us a copy. Reinman’s signature is in longhand, unlike the comics version but almost identical to the one on the synagogue drawing.

Alice and Alex had settled in Boca Raton, Fla., and it was probably to be near them that Paul Reinman moved to West Palm Beach (with his second wife, Celia; Dora had died in 1967) when his comics career petered out in the mid-1970s. Debi Murray of the local historical society helped us look up their records. There Reinman turned to courtroom sketches for TV, movie posters, and advertising. His last boss at Marvel, Roy Thomas, wrote apologetically about Reinman and several others in a 2004 number of Alter Ego fanzine, which we downloaded from John Morrow’s vast collection: “Nobody gave them retirement parties, a pension, or a gold watch. One year, they were making a decent living drawing. … The next, they had somehow lost their footing, never quite to regain it.” In the same issue, Nick Caputo called for a reassessment of Reinman’s art—which had long been belittled by many as “second rate” or even the “worst.”

This disdain was partly a result of intra-industry rivalry; Reinman had left Marvel to start a competing superhero series with his first employer, Archie—which failed, forcing his humiliating and brief return. Caputo blames this mainly on inferior writing and has kind words for Reinman’s work at its best: “moody pages, filled with interesting layouts, innovative angle shots and impressive, detailed backgrounds.” Another enthusiast, on one of the many comics discussion boards, went so far as to compare Reinman with the classic Japanese artist Hokusai, citing their similarly graceful brushstrokes. Stan Lee (Lieber), the revered comics writer—most famously for Kirby—who preceded Thomas at Marvel, may have pointed to the key: “Reinman was good because he was also a painter, and he inked in masses like a painter.”

For all his success in commercial art, Reinman never gave up painting, at a level that is all the more impressive for being self-taught. It was here that his background found some direct expression: Sheila Schechtman, a retired teacher, shared with us a lithograph of his that shows three tallit-wrapped, bearded men at a synagogue bimah, one of them lifting a Torah scroll. Though undated, it clearly was made in the United States, as it bears Reinman’s comics-style signature in the block. There’s not enough detail to tell for sure whether it depicts memories from Worms, as I suspect, or an American scene. The print is numbered 187 out of 200 (next to a penciled signature in his old script style but with a single “n”), so there must have been enough demand to turn out such a large edition. But that’s the only other example we’ve found of Jewish subjects in Reinman’s fine art.

As a watercolorist, Reinman won awards in Manhattan’s Washington Square outdoor shows. Sadly, this appreciation didn’t last for any of his work outside of comics. Marvel’s parent company did commission him to adorn its cafeteria with a mural—but of all its superheroes. A single page of X-Men No. 1 that he inked in 1962 was auctioned for $45,000, thanks to Kirby’s signature. Covers penciled and colored by Reinman himself have sold for up to $1,400, mainly from the mid-1940s Green Lantern series, which Thomas and others admire as his finest work. In contrast, last year an oil painting (again with a two-digit date, “63”) was offered in a “Boca Raton estate sale”—was it the Leopolds’? Hood Auctions kindly permitted us to reproduce it here. It failed to make its low estimate and fetched merely $100. Our own purchase, then, was not much of a bonanza in dollar terms.

That inexpensive painting is a dreamy Winter Street, Lady With Umbrella that features masterful rendering of reflections on a wet pavement. For a Who’s Who in Comics in the 1960s, Reinman listed as his “influences” Alex Raymond of Flash Gordon fame—and the French Impressionists. But in our view, the painting is eerily reminiscent of the interwar German post-impressionists, many of them Jewish—especially the rainy Berlin street scenes by Lesser Ury. So, it seems that Reinman did keep something of the old country close to his artistic heart.

And then there’s his memento of the Worms Synagogue, whose path to Jerusalem we’re still trying to trace.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Gideon Remez is a research fellow at the Truman Institute of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Gideon Remez is a research fellow at the Truman Institute of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.