During the tumultuous summer of 1968, I took off for a vacation with Ilene, then my fiancé, to Nova Scotia and nearby parts of Canada. We drove for two days to Cape Breton, which, according to the guidebook that the poet Sharon Olds had given us, had the most spectacular island views in the Western Hemisphere. All we saw, from beginning to end, was pea soup fog, into which Ilene threw the guidebook from the car window, which was a good reason to marry her. Peggy’s Cove was pleasant, as advertised, and we spent a few days on Prince Edward Island, where to our horror we watched on a tavern television Mayor Daley’s thugs beating up Abby Hoffman’s demonstrators at the Democratic National Committee’s meeting in Chicago. If I were writing my own guidebook of the area, I would recommend the oat cakes.

Now to where this story really begins, Montreal, to take in the remains of the 1967 World’s Fair, which had been renamed “Man and His World.” For three nights in a row we returned to the India Pavilion. Yes, because after the oat cakes the food was spectacular, but also because of a painting that we could not stop looking at. It was enormous, 82 inches by 68 inches, and hung on invisible wires over a garden of bright white pebbles. Orange, white, and green and pretty much abstract, it had a figure that might have been a boxer at the middle. Here is an image of it:

We sought out the manager of the pavilion and asked whether we might buy the painting once the exhibition closed. This kind man saw at a glance that we hadn’t a Canadian penny, and offered to send the work to our apartment in New York and even—if I remember correctly—pay the shipping expenses. Our vacation completed, we got in our Opel and drove home.

Some months later the painting, still in its stout wooden frame and with three black-and-white proofs depicting its development, arrived at our West 87th Street apartment. Somehow—I’m not sure it fit into the elevator—we got it to the fifth floor, and when we turned it around, we at last saw the painter’s name, Vivan Sundaram, and the title of his work: “It Was a Great Day.” We also saw the mysterious word SLADE, and the less mysterious FOR MONTREAL, with the price—200 British pounds—that we did not have to pay. We hung it high on the only wall large enough to contain it. For us it was a great day.

We have had this painting now for over half a century. It has undergone a number of vicissitudes. From 87th Street we moved it to West 82nd (thank you, Carmelo, the doorman, who helped get it upstairs) and then to my office at Boston University. There it sat for decades until I was deposed as head of the creative writing program and the new director, in his eagerness to take over my office and its view, ripped the canvas, a 2-inch gash.

I sought out the best restorer in Boston, only to discover that the cost of repairs might at one time have paid for the “Mona Lisa.” But then it turned out this gentleman—if only I could remember his name!—was no less kind than the manager of the India Pavilion. He was a Red Sox fan and, upon learning that I was the father of the general manager who had broken the 86-year curse upon the team, he did the restoration for free. We could change the title of the painting to “Invisible Mending” because not even the greatest expert could find the slightest trace of the damage done.

It turned out that the office of the outcast director was too small for the painting, so we rented a U-Haul and took it up to the place we own with my daughter and her husband in Deer Isle, Maine. There it has hung, high in a place of honor near sun and sea for many years—until this summer, when I discovered after the long drive from Boston that it had been removed and placed in ignominy, upside down and facing the wall. This was half a gag and half done in earnest by my son-in-law, the actor and writer Dan Futterman. (True, I had pulled a similar gag with one of his paintings a few months before: humor among the Epsteins.) What was serious about this was the realization that Danny didn’t like the painting all that much and, even more serious, was the question of my own mortality. What would happen to “It Was a Great Day” after Ilene and I were gone?

Driven by these thoughts, and on impulse too, I contacted a number of galleries in New Delhi to ask if any of them knew how I might contact Vivan Sundaram. One gallery wrote back saying that they had a long relationship with the painter and supplied me with his email address.

I wrote to him about Montreal and the food and the white pebbles and all the rest, ending like this:

It is just as beautiful and powerful and meaningful to us now as it was then, when our lives together were just starting out.

I hope that seeing it now will bring back some memories and give you a bit of the pleasure we have had in it over all these years.

Almost at once I got a reply that expressed his wonderment that the painting had been rediscovered and describing his intentions when he created it. Here are parts of what he wrote me:

I was overwhelmed to see my painting, which I believed was lost … I am so very touched by the way you write how my painting marks the moment of your marriage fifty-five years ago, the pleasure it has and still gives you and your wife. It is known that living with paintings can become part of a personal relationship—you use very expressive words: beautiful, powerful and meaningful, placing them in a temporal trajectory.

I am curious to see the drawings in which you discerned my outrage to the war in Vietnam as early as 1967. My first expression of solidarity against the war was to be present[ed] at the famous 17 March, 1968 demonstration in front of the American Embassy in London. My graduation was in June 1968.

This painting is one of seven works I refer to, as my London paintings. This body of ‘student’ work has acquired a historic status! The MET in New York, which acquired one of these paintings titled ‘From Persian Miniatures to Stan Brakhage,’ placed it in an exhibition called ‘Epic Abstraction: Pollack to Herrera’, which opened earlier this year.

Best wishes to you and your wife,

Vivan

I did look up those three proofs and, indeed saw the jet planes and what looked like bombs over a village, all of which faded from drawing to drawing until reaching a level of abstraction in “It Was a Great Day.”

I then wrote back asking Vivan if he knew my cousin, Harold Leventhal, the manager of great American singers like Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins, Joan Baez, and just about anybody else you can think of in that great era of folk and popular music. As a private in the U.S. Army, he was stationed in India from 1944 to 1946 and, already a member of the Young Communist League, he sought out the leaders of Indian independence, meeting and getting to know Jawaharlal Nehru,Krishna Menon, and Mahatma Gandhi. Martin Luther King later asked Harold to tell him what he knew about Mahatma’s tactics of nonviolent resistance. When I came east to college, I saw that the walls of Harold’s apartment were covered by large and luminescent paintings from India that he had collected over the half century since his time stationed in that country.

Vivan wrote back saying he had found a photo of the (young) communist Harold sitting with “Sunil Janah, the legendary Communist photographer.” I hoped that our correspondence, and something like a friendship, would continue. But when I opened the Times of April 12 of this year I saw:

Vivan Sundaram, 79, Dies; a Pivotal, and Political, Figure in Indian Art

That obituary, written by Holland Cotter, took up almost the whole page and told me much that I did not know, including the international stature of the artist, his lifelong struggle for social and economic justice, and the fact that, on his mother’s side, he was Jewish. The article ended by confirming what I did know or had sensed when seeing the thesis painting and proofs that he had completed at the age of 24. “I am a child of May ’68, the kind of freedom it gave,” he said in a 2018 interview with The Indian Express. “Something in that historical moment urged me to continuously question and shift, both thematically, politically and linguistically, in terms of art. Connecting with people from different disciplines has always informed my work.”

That same month, I wrote to Vivan’s gallery in Dehli to tell them how sorry I was that they had lost their client and friend. They wrote back inquiring whether I might now be interested in selling “It Was a Great Day.” They told me they thought it would be worth $100,000 to $150,000. I had not, until that moment, entertained such a notion.

Well, a caveat: Danny Futterman’s gag, together with the surprise at finding myself an octogenarian, had sent up in my mind a trial balloon filled with the gas of worry and a soupcon of avarice. That may have played a part in my impulse to contact the artist in the first place. A more important reason to take the gallery’s suggestion seriously was this: I knew that spring that I would be producing an off-Broadway production of the play I had made out of my novel King of the Jews. That meant I had to come up with at least $350,000 by that fall, when the play would be mounted at the HERE Theater in Soho. Suddenly I’d have a third of our budget in my pocket.

When I was studying in England in the very early 1960s, I came across a paragraph in one of the first really good books about the Holocaust, The Final Solution, by Gerald Reitlinger. That paragraph described Chaim Rumkowski, the elder and lord and master of the Jewish Council in the ghetto of Lodz. He rode around with his lion’s mane of hair and his black cape, put his picture on ghetto money (to buy nothing) and ghetto stamps (to send mail nowhere), and decided which of his fellow Jews should or should not be sent to their deaths. His clever scheme—which would have worked if the Russians had continued westward instead of cynically stopping midway through Poland—was to have the cotton mills of Lodz make the uniforms for the German army. He might have been a hero, with statues to him in New York and Tel Aviv; instead he was despised by the few who survived the liquidation of the ghetto.

How to judge him? It’s not easy. When I think of him, I usually rely on a story from the Talmud, where the question is posed: May a starving Jew in a forest eat the four bird’s eggs he finds in a nest? Yes, say the Talmudists, but first he must throw a stone into the nearby bushes so that the distracted mother bird will not have to go through the agony of seeing her little ones devoured. Rumkowski did not throw that stone. That is, he took pleasure in his power, instead of exercising it with sorrow, regret, and empathy.

Fifteen years later, In New York, I rediscovered that account of Chaim Rumkowski in my dog-eared copy of The Final Solution and decided to write a novel, King of the Jews, based on the paragraph it contained. The book was despised by those Jews who did not want to face the complex nature of Jewish collaboration or to see the Holocaust touched by the feathers of humor (see my essay “The Milk Can,” previously published in Tablet). But other Jews felt differently; the book is still in print after being translated into a dozen languages and it has become, or so I’m told, something of a classic of Holocaust literature. In the early 1980s I turned it into a play of the same name, and after many adventures it was produced with enormous success in Boston and a few other places.

Now it has come to New York, and once more I’ll judge Rumkowski, that king of the Jews, but without the wisdom of the Talmudists. I have come to only one conclusion, as worthy and useless in the world today as it has always been: from Haman to Hitler to Hamas. Human beings cannot be allowed to find themselves in inhuman situations.

But now, back to my considerations about selling that painting.

“Don’t you dare!” cried Ilene, who was as amazed at finding herself an octogenarian as I. She didn’t mean that we could not sell a treasure we had enjoyed all our lives together, but that we might be able to get a lot more. She wanted research. It didn’t take long to discover that at that very moment Vivan had a major installation at the Tate Modern, which also was displaying—as if to prove that even in death he remained true to his word—a beautiful painting titled “May, 1968.” The Met in New York owned and had shown a sister painting to “It Was a Great Day.” An exhibition in Munich was filled with more large, resplendent works from that same London cycle. But I had his thesis painting at the Slade School of Art: The price was going up.

I began to contact South Asian art experts at museums and universities. One wrote back to a gallery owner as follows: “Leslie Epstein has a large, important, and beautiful painting by a great artist. It is worth more than $200,000. He should take it to auction.” An auction! Do I hear $500,000? The same day I called Sotheby’s in New York and talked to their expert on contemporary Indian art. I sent her the image of the painting, the three proofs, and Vivan’s letter saying how moved he was to discover it had not been lost and what an important place it held in his oeuvre. Almost at once I heard back: Sotheby’s wanted to place “It Was a Great Day” in their fall London auction—wanted to do it so much, in fact, that they would cut their commission and pay for photographing, restoration, and all shipping costs.

At this, the extremely nice expert must have sensed my hesitation, because she asked me where, all financial considerations aside, I would like the painting to find a home. I said my wishes were what I thought Vivan’s would be: in an Indian museum, so that his countrymen could come to know and appreciate it over many years. “Give me a week,” she replied.

Just two days later she had an offer from a celebrated museum in New Delhi. While I was mulling over this proposition—it was for the same $200,000 that the expert in Boston had said was insufficient—a complication ensued. Vivan’s gallery had somehow gotten wind of the fact that I had given Sotheby’s a one-week exclusive and nonetheless contacted the museum, which now said they would work solely through the gallery and not the auction house. I will spare you the complications that ensued and provide the end result: Sotheby’s graciously withdrew (though maintaining their wish to send the work to London in the fall) and the gallery and museum made me a final offer of $250,000 net, which means the actual bid must have been close to $300,000. Who would have thought that Ilene and I, sitting over our tandoori chicken, were gazing up at an orange-colored boxer who would win such a championship prize.

Meanwhile, I had begun to make payments from my bank account to the LLC that was funding the production of King of the Jews. Thousands for a rehearsal hall, thousands for the set and lighting designers, and thousands more for a contract to hold the theater. I had managed to raise $80,000 from generous friends, but I soon would have to draw significant amounts from my retirement accounts, never a good idea. I told my family—Ilene, of course, and my three children, Paul, Theo, and Anya—that I did not wish to send the painting abroad for auction but wanted to accept the offer from the museum in New Delhi.

“No! No! No!” they cried in unanimity. “Think of Jimmy!”

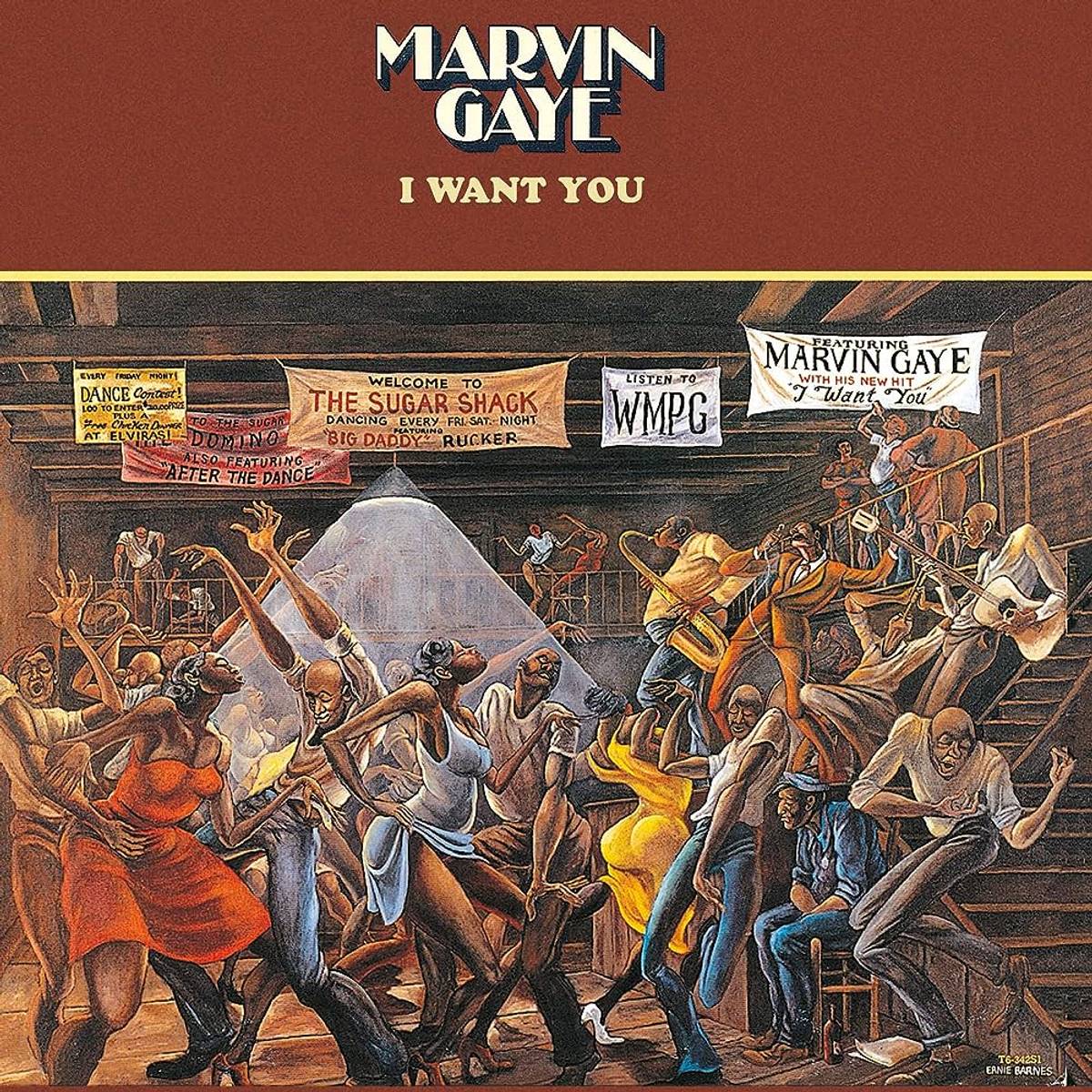

I shall explain. Jimbo was (I use this sad verb because he died recently of pancreatic cancer) my oldest friend, my first cousin, and my genetic half-brother (his father and mine, respectively Julius J. and Philip G. Epstein, the writers of Casablanca, were identical twins). Jim played football at Stanford and later struck up a friendship with Ernie Barnes, the famous Black artist who had played for the San Diego Chargers and Denver Broncos. Jim commissioned Ernie to paint portraits of his dogs and then bought a number of his other works. When he admired Barnes’ painting on the cover of Marvin Gaye’s I Want You album, Ernie said, “Give me a thousand dollars and I’ll make you an exact copy.” Done! Whenever I visited Jimbo at his house in Encino, I’d always admire the “Sugar Shack” replica, which hung above the table where the two of us would play poker.

One day a stranger knocked on my cousin’s door and offered him $300,000 for the painting. Jimmy said no—until maybe a year later he said yes, this time for $600,000. Fast forward one month. There sits my cousin at the breakfast table, opening his copy of the Los Angeles Times. Christies auction house had just sold his painting for—hold onto your hat, Jimbo!—$15.3 million.

Thus you see the sugarplums dancing in my children’s heads. I admit to some candied fruit whirling in my own. Imagine, as I did, two dot-com entrepreneurs with artistic pretensions, bidding against each other: 5 million, 10, never mind—15, for “Sugar Shack”: If Mohamed bin Salman was willing to pay half a billion for a half-authenticated da Vinci, what would he fork over for a signed Sundaram, hung once on wires over a garden of pebbles? Why, it was made for the dust and dunes of the desert. On the other hand, as I soon discerned, the most Vivan had ever received for any of his works at auction was $67,000. Wasn’t the offer from New Delhi a big jump from that?

What to do? Take that bird in the hand or the flock that might be hiding in the bush? Then, while I dithered in increasing anguish, I was informed that I had to transfer $30,000 to our LLC to pay for an Actor Equity bond. That would be the end of my money market account. The people in India told me that they would not touch the painting in Maine until the entire $250,000 was deposited into the Brookline Bank. What if there were no dot-com entrepreneurs? What if MBS were too busy thinking of the next person he wished to dismember or was saving his billions for Jared Kushner’s Affinity Partners or decided to buy half the soccer teams in Spain? I could end up with no choice but to raid my TIAA account. I signed up with the museum and made peace with the idea that “It Was a Great Day” would be admired by the millions of New Delhi and perhaps more millions in what used to be called Calcutta and Bombay.

End of the story? As of this writing, perhaps not quite. No part of the sums owed me have yet appeared in my account. And last Wednesday, Dick Celeste, the former governor of Ohio and a pal from our days at Oxford together, flew into town from Colorado with Jacqueline, his wife. Back in the 1990s, Bill Clinton had made him our ambassador to India and he—rather like Cousin Harold—had kept ties with the country since. Indeed, he and his wife are preparing to take a trip there this coming winter. Over our eggs Benedict at the Café Landwer on Beacon Street, Jacqueline told me that she knew an enormously wealthy woman in India who had a passion for collecting contemporary Indian art. Would she like me to ask her if she were interested in Vivan’s great painting? Sugarplums! Money from the Maharani! I should have said, But I already agreed to sell it to a museum in Delhi. Instead, I said, Sure, ask her. It’s 88 by 66 inches.

And that, as of this writing, is where things stand. Perhaps there will be a postscript. Meanwhile, “It Was a Great Day” sits in Maine, right side up but still facing the wall. The shippers will come for it. But no one knows when that will be or which of the seven seas it will cross.

Leslie Epstein teaches creative writing at Boston University. His three Leib Goldkorn books were recently published as The Goldkorn Variations: A Trilorgy (no typo). His play King of the Jews runs from Oct. 28 to Nov. 18 at the HERE Theater.