Ordinarily, objects in the rear-view mirror get smaller as you leave them farther behind. But with every generation that passes, the Lower East Side seems to loom larger in the American Jewish imagination. It’s not just that prosperous hipsters are moving back into the streets that once overflowed with their great-grandparents. Even for Jews who never set foot on Delancey or Orchard Streets, the Lower East Side remains an imaginative homeland. Most American Jews can trace their family history back to the neighborhood: Of the 2.5 million Eastern European Jews who immigrated to the United States between 1880 and 1924, three quarters lived on the Lower East Side. Few of them stayed, however. It is easy to forget, looking at sepia photographs of teeming tenements and Yiddish street signs, that the Lower East Side was a place Jews usually wanted to leave as soon as they could, for the more spacious precincts of Brownsville, Harlem, or the Bronx.

The Eldridge Street Synagogue, whose story Annie Polland tells in her lively and insightful new book, Landmark of the Spirit, encapsulates the whole arc of this New York Jewish history. When the cathedral-like synagogue opened, with a public celebration on September 4, 1887, it was an unmistakable declaration that Eastern European Jews had arrived in America.

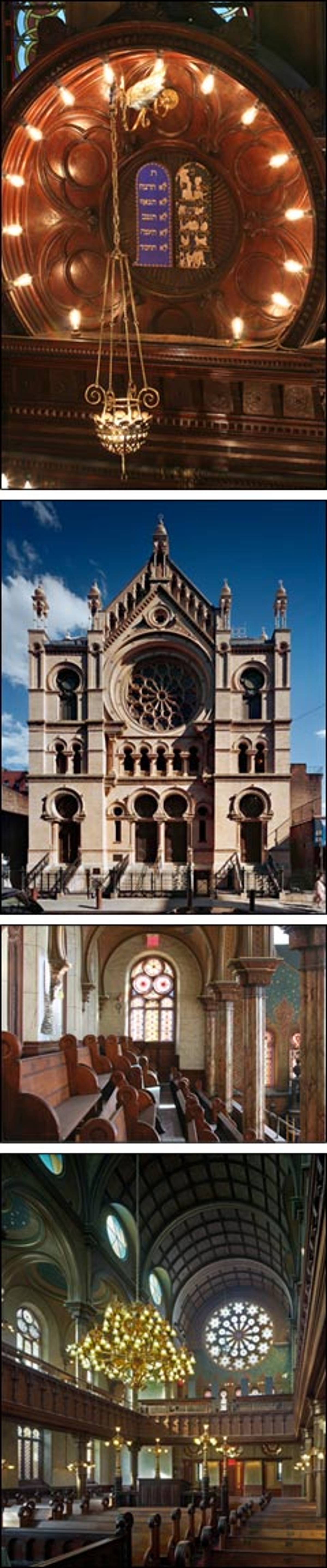

For the first time, the Lower East Side’s Orthodox Jews would worship in a magnificent, purpose-built structure—there was seating for 740 worshippers—instead of the usual shtiebel tucked away inside a tenement, or at best a rented church. “In 1887,” Polland writes, “nothing in the neighborhood’s architecture announced the Jewish presence as strikingly as the Eldridge Street Synagogue did.”

The building’s Romanesque design, reminiscent of so many Christian churches (and executed by Catholic architects, the Herter brothers), was given a distinctly Jewish inflection. The Moorish-style keyhole windows invoked the architecture of medieval Jewish Spain, while the central “rose” window featured twelve Stars of David, an allusion to the twelve tribes of Jacob. Nor were references to the building’s New World environment lacking. Flagholders at the windowsills featured five-pointed American stars, to complement the six-pointed Jewish ones, and were used to display American flags. (All of these architectural details, and many more, are beautifully documented in the book’s color photographs.)

When the Eldridge Street Synagogue was built, there were already some impressive synagogues in New York, like Temple Emanu-El on Fifth Avenue. But that was a Reform temple, built by and for the older, richer, more established German Jews uptown, who looked on their downtown brethren with a combination of concern and disdain. Polland quotes the exquisitely nasty report on Eldridge Street’s opening-day festivities published in the Reform Movement’s journal, American Israelite. Writing under the pseudonym “Mi Yodea” (Who Knows), a reporter contrasted the “elegant simplicity” of the synagogue with the noise and vulgarity of the congregation: “women sparring over a balcony seat, ‘gentlemen’ who retained their cigar stumps with the intention of smoking them on the street after the dedication, and babies incessantly crying. He also mentioned ‘loud talking’ during the ceremony and ‘the running to and fro of the trustees as well as the public during the lectures and singing.’”

In reports like this—and in the many court records, board meeting minutes, synagogue publications, and interviews that Polland has ingeniously compiled—we can see how Eldridge Street, thanks to its size and prominence, became an important venue for debates about how Judaism should adapt itself to America. Simply building the synagogue, at a cost of more than $90,000, was a way for this congregation of immigrant manufacturers and merchants to show that they had made it in the New World. Polland pays due respect to the rich men, and their influential wives, who made Eldridge Street possible: men like the banker Sender Jarmulowsky, the first president, who combined Talmudic knowledge with business expertise. In his day, according to the Yiddish Tageblat newspaper, “Sender Jarmulowsky was a name that was known to every Jew in the old and also in the new world.” Today, practically the only trace of the name that remains is an inscription on the façade of “S. Jarmulowsky’s Bank, Est. 1873,” on the corner of Canal and Orchard. Then there was Isaac Gellis, the kosher-meat tycoon, who boasted that his was one of the first Jewish businesses in New York: older than ALL of the existing Jewish institutions; “older by ten years than the Jewish mass immigration from Russia and Poland,” according to one of his advertisements.

These were the men who paid the pledges and made the loans that kept the Eldridge Street Synagogue afloat. They also coughed up for the star cantors who were, in the 1880s, a sine qua non for any fashionable congregation. Polland offers a fascinating capsule history of the period’s “cantor wars,” which saw Europe’s most learned and talented singers flock to New York for enormous salaries. Eldridge Street managed to hire one of the greatest cantors in the world, Pinhas Minkowsky from Odessa, who asked for, and got, $2,500 a year. As Polland shows, Minkowsky was as vain as any opera singer. He wrote in his autobiography that “the congregation often boasted that Minkowsky ‘beat’ all the other cantors,” and he eventually quit Eldridge Street when the synagogue refused to pay him a $500 bonus, declaiming, “You have shattered me for no good reason and you have hurt my pride.” Perhaps such prima-donna behavior was only to be expected at a time when one synagogue Polland mentions advertised its cantor as having a voice “five hundred times stronger and sweeter than Caruso’s.”

Here was another kind of Americanization, the craze for celebrity and the competition for status; and it did not go uncriticized at the time. Indeed, the Eldridge Street Synagogue itself was attacked for ostentation: One critic spoke of “a Judaism composed of carved wood and ornamented bricks and covered up by a handsome mortgage.” Yet as Polland shows, during its first 50 years, the synagogue found creative ways to reconcile tradition with modernity. Members were supposed to be shomer Shabbos, for instance, yet this was hard to keep up in a country where Sunday, not Saturday, was the day of rest. Women prayed in a separate section, but the curtains meant to conceal their balcony from the men below were usually left open. Conflict and compromise were the stuff of daily synagogue life, then as now.

Finally, however, demographics presented the Eldridge Street Synagogue with a challenge that could not be finessed. By the 1930s, with the immigrant flow from Eastern Europe cut off and local Jews moving up and out of the Lower East Side, the congregation began to age and shrink. In the postwar era, the main synagogue was boarded up and services moved to a chapel; the building itself began to crumble. It took the determined efforts of the Eldridge Street Project, launched in 1986, to raise the funds to restore the synagogue to its original state. The building reopened late last year as the Museum at Eldridge Street and is open to the public for tours during the week. But not on Shabbat: for the last 121 years, Polland writes, even at its lowest ebb, the synagogue has never missed a Shabbat service.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.