A Lavender Marriage, 2019

A story of painted portraits and meetings in the park

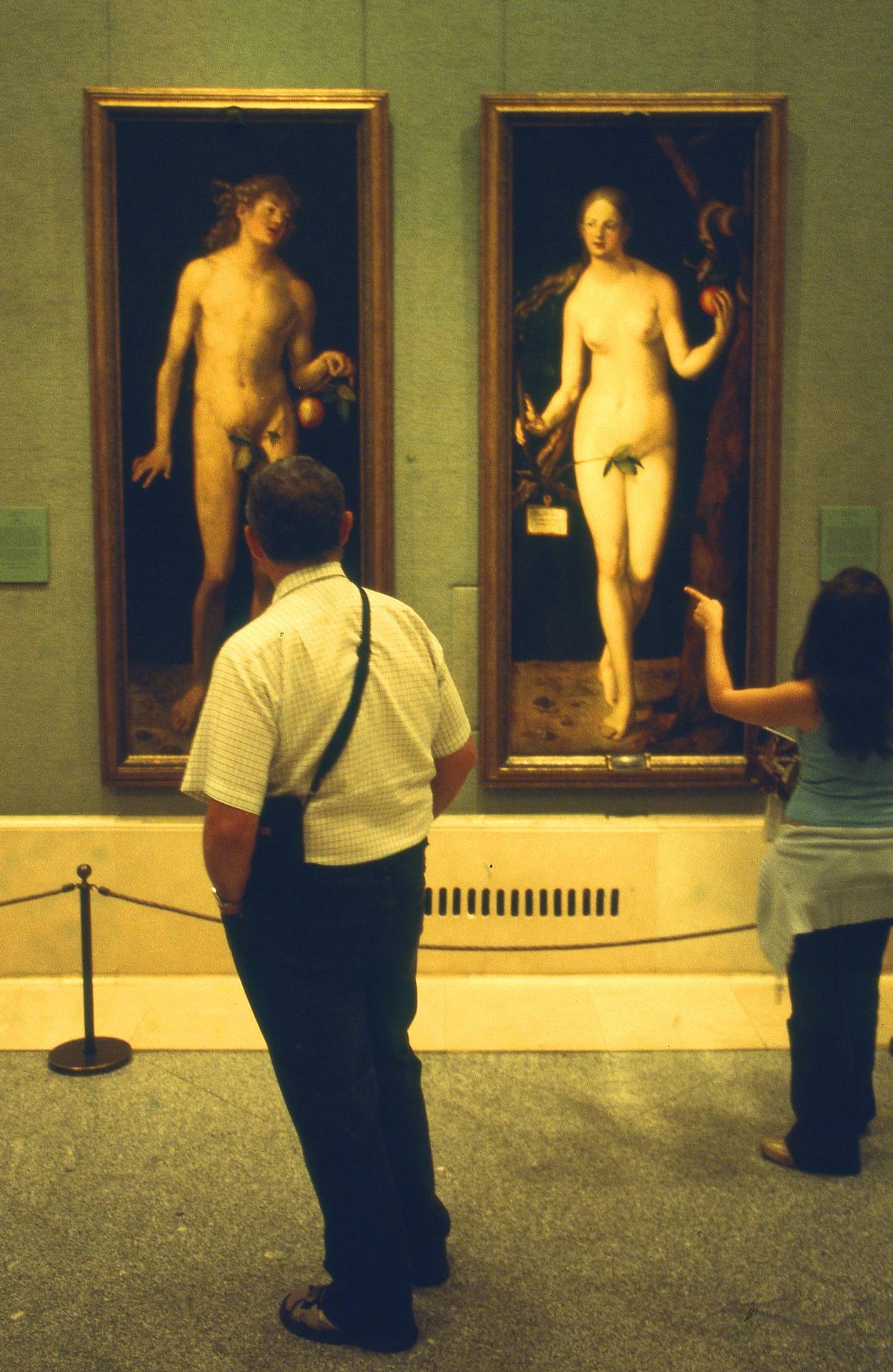

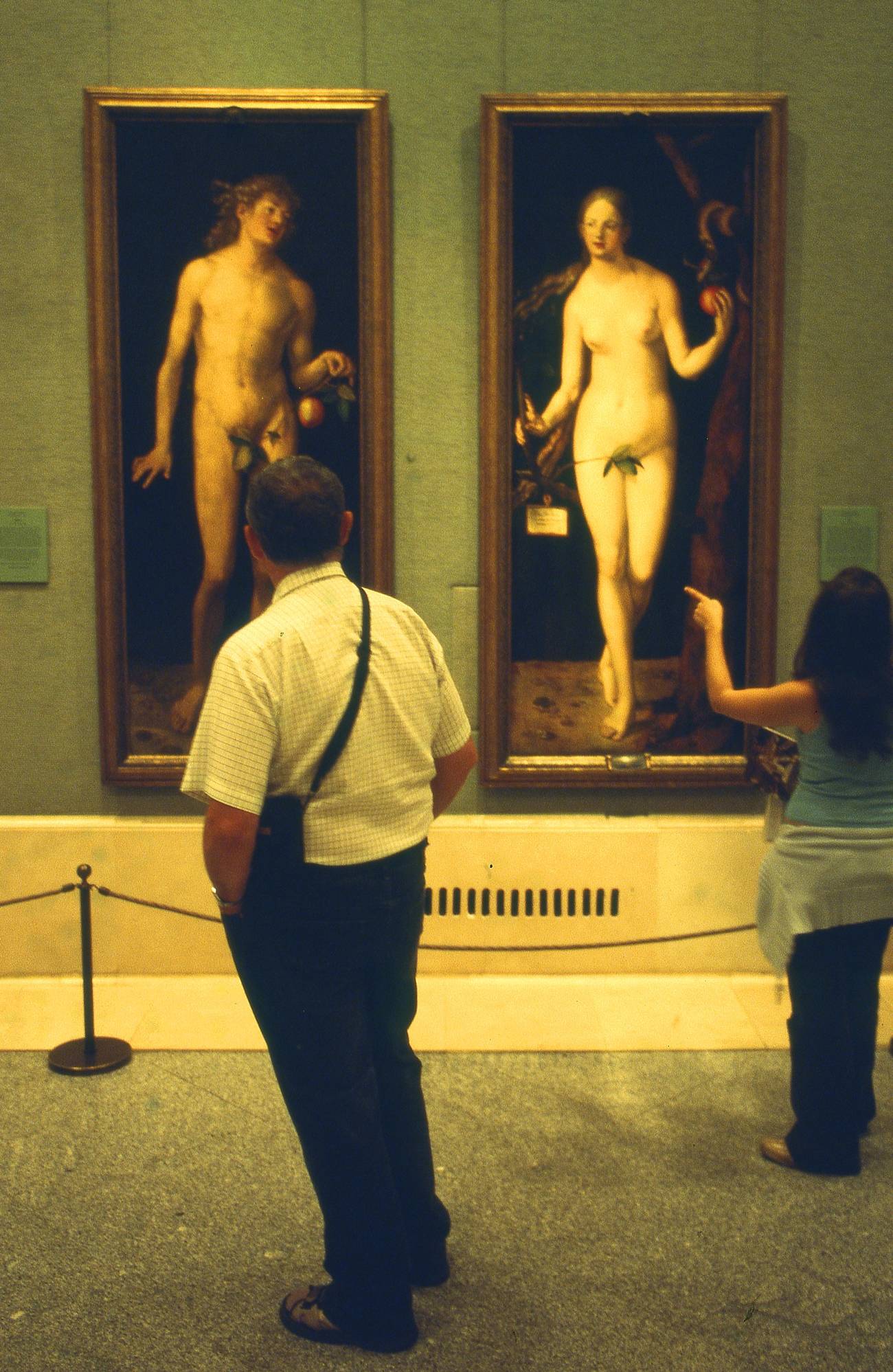

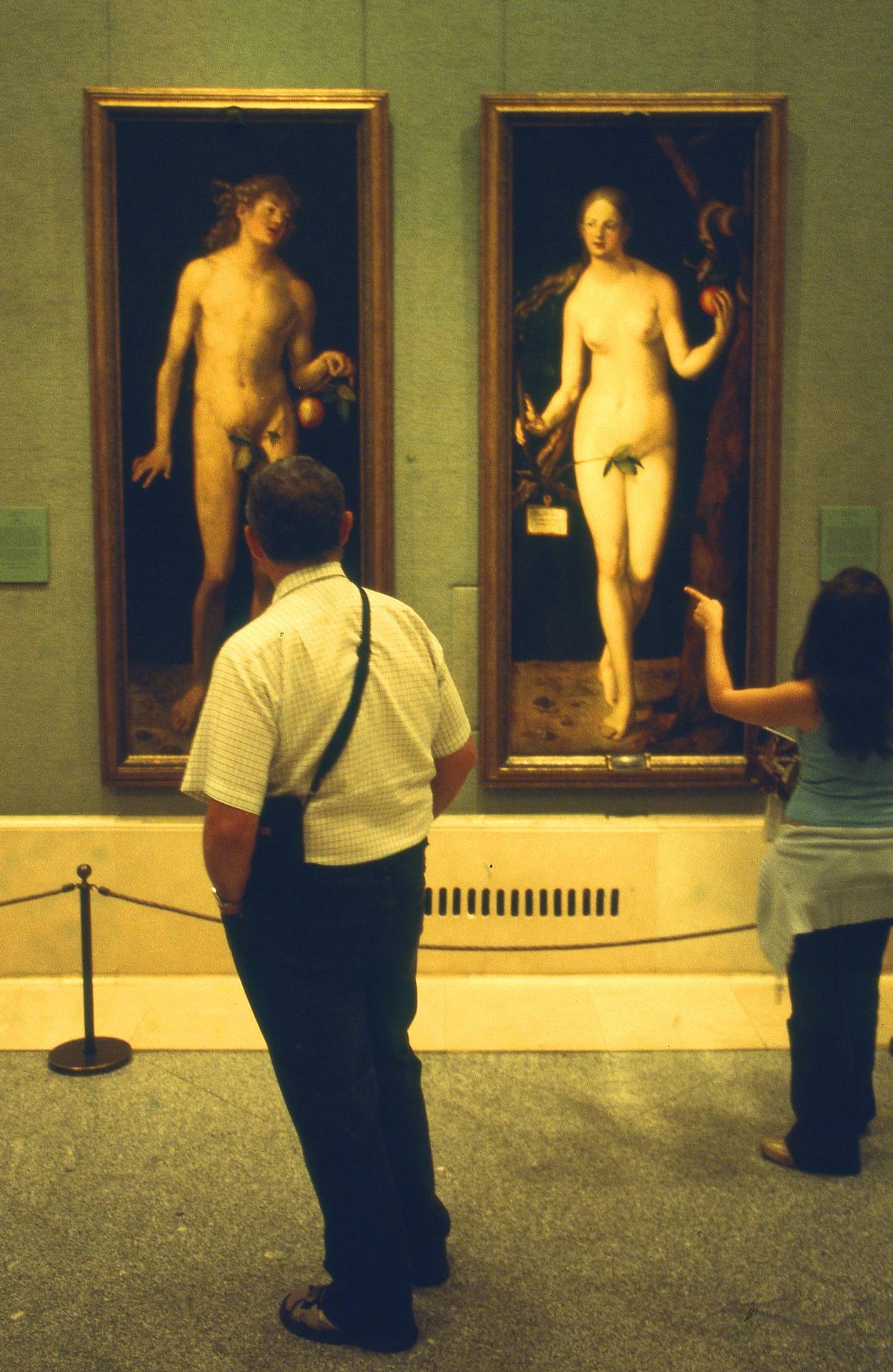

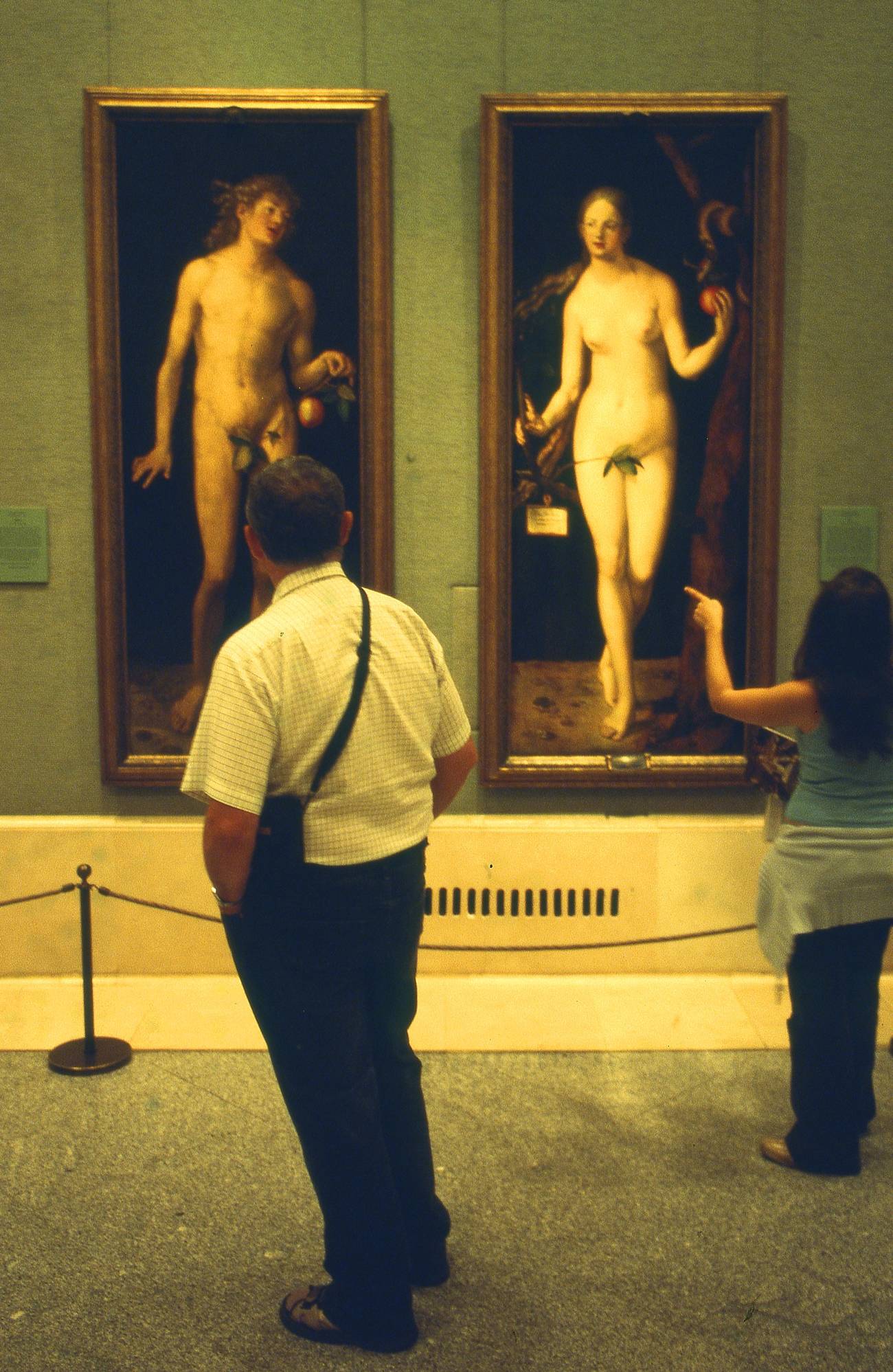

I was trying, that August afternoon, to copy the Renoir nude that hung in room 821 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Set in a landscape of grasses and sky and a glimpse of what is almost certainly the sea. Hair: brown and in a braid. It’s an homage to Ingres’ “La Grande Odalisque.” To me, she’s half asleep, propped up on her elbow. There is no curving, ivory spine, nothing of the courtesan’s unforgiving gaze. How that look goes right through the viewer! It went through me when I was 20 and at the Louvre; I felt myself turning into the same block of ice that the masterpiece seemed to be carved from. The French, glacial themselves, wouldn’t let a kid set up his easel in front of it. I copied the Picasso version instead: all angles, blue, white, burnt sienna, a sort of African flag.

I didn’t hear Uncle Jack come up behind me. I guess I was daydreaming.

“A good choice, Saulie. Beautiful. And I don’t mean the clouds in the sky.”

He gave me a playful punch in the shoulder. I put down my brush, tipped with the same blue I’d seen in the skin of her back and buttocks as well as, more conventionally, in the heavens above.

“I know you don’t, Uncle Jack.”

He loomed high above me, grinning. He gave me a second poke, a little more forceful than the first. “I like when you paint the girls. Sometimes you do those Greek statues. Sometimes you do the naked men and the boys.”

“I’m an equal opportunity establishment,” I said.

“Yeah, I know you are.”

I didn’t know what to say to that. I used a palette knife to tip a little titanium white into my puddle of blue.

Uncle Jack wasn’t done. “A disappointment to my brother.”

In other words, to my father, though for the last 13 years Uncle Jack had been my father. And he—not Stanley, and not Mom, either—had been the one to express his dissatisfaction. Sally, he called me now and then, pretending it had been a slip of the tongue. One time, at the top of his place in Battery City, he’d introduced me to two or three people from his real estate gang. “I’d like you to meet my niece.” There was no pretending that time. I wanted, naturally, to jump out the window and fall 43 floors to the ground.

I twisted my brush into the new mixture of pigments. I had a choice: the patch of the sea, the swatch of the sky, the little shadowed hollows above the sleeping girl’s rump. Uncle Jack moved to my side. The little tendril at the end of his belt hung before my eyes. “I’ve got something I want to talk to you about,” he said.

“What’s that?” I asked, deciding on the safety of the half-hidden sea.

“It’s what I would call a private matter.”

He glanced around, and I glanced around, at the score of people in the room. Of course they all had their little museum buttons in their lapels. A tour guide was talking about Monet’s “The Stroller.” Quite incorrectly, from the snatches that wafted across the room. Two women were walking toward the Renoir; they leaned toward my reproduction, on which the wet oils gleamed in the overhead lights.

Big Jack, a name I no longer used to his face, jerked his head over his shoulder. “Not here. Let’s go to the Shimonov Terrace. I’ll treat you to your cup of tea.”

He turned to the door. As if harnessed to him, I rose and followed a step behind. He tipped his hat to the guard. “Keep an eye on all that, will you, George?” He meant my easel, the paints, the canvas. “Genius at work.”

The Black man came close to attention. “Of course, Mr. Shimonov. It is good to see you here.”

We trudged along through hallways and up stairways, each caught in his own train of thought. I was somehow back in the summer after my junior year, traipsing through one room after another of the Louvre.

Up near the rooftop, my uncle broke his silence: “Those Greeks! The gods and the mythological people. You can barely see their penises. No wonder their civilization collapsed.”

We arrived at the Shimonov Terrace. Actually, as the bronze tablet made clear, it was the Henrietta Shimonov Terrace. She had given the statues—a Maillol, a Degas, a copy of a Donatello David, who, small penis or not, stood over the head of Goliath—scattered over the terracotta. Uncle Jack was the one who insisted they be brought together on this spot that his $11 million transformed into an outdoor cafe. It had been something of an industrial dump, with a shed and whirligigs for the air-conditioning. But Aunt Henrietta used to come here, especially after she had become ill, and peek over the railing to the treetops and the pond, whose water was sometimes green but now and then, depending on the light, ultramarine. Like the gown of the Virgin Mary.

We sat at a corner table while a succession of waiters brought me my tea in a pot and a pile of pastries; Big Jack started with vichysoisse, with little green bracelets of scallions trembling on top. “Eat those fig things,” he said. “Eat those things with the strawberries.”

It was a warm day with high, ponytail clouds. A breeze fluttered the napkins. I nibbled, as directed. “Everything OK with you, right, Saulie? I mean you like the job with the paintings? You like the apartment? Not so many people get to walk to work. I don’t get to, for instance.”

“Everything is fine, Uncle Jack.” I had learned not to add, Thanks to you.

“And on the personal side? You seeing anybody at present? That Yale girl? The one in your class? She had hair, puffed up, like a rabbi’s hat.”

“Susanna? Not for a a while. She moved to California.”

He had a moustache; it looked as if had been painted on with a grease pencil. He wiped, with a finger, the soup that clung to it. California: It was, I knew, a fraught word, and for half a moment neither of us said anything to the other. I hadn’t been back since Jack had swooped in to the John Wayne Airport on his private plane and flown me away to New York. It seemed the same day, but of course we stayed for the funeral. Stanley and Rosemarie were put into boxes, they looked like shoe boxes, only bronze; they were inserted side by side into a marble wall. I knew there had been an accident, a car crash, but it wasn’t until I was belted into the Gulfstream, that I learned what had happened.

“What happened,” said Uncle Jack, who was walking up and down the aisle, “was a terrible thing. Really terrible. They were in that little MG they liked to drive around in. It was an affectation of Stan’s. I couldn’t fit in. You know that fire house on Sunset? At Beverly Glen? There must have been a five-alarm job somewhere, a conflagration, because the fire truck came roaring out and made a right turn and didn’t see them at the light. Crushed. So flat—and this is the good news—they didn’t feel a thing. The doctors assured me.”

A waiter removed his bowl of soup. Another waiter brought a plate of steak frites. “You sure you don’t want anything, Mr. Skin-and-Bones? I can see your skeleton, for Christ’s sake. Right through your clothes. It’s like Halloween.”

Because he had hung his jacket on the back of his chair, I could see something, too: his pink breasts, like a female’s, sweating through the white cotton of his shirt. He’d first started to push food on me while we were 30,000 feet in the air. “You’re 14. It’s a crucial age. You establish with the cells of your body a pattern. Henrietta is going to fatten you up. She’s a hell of a cook. I could hire a chef, but she wants to make a fricassee or a beef Wellington and I like the way she does it. No wonder you want to be a painter: paint brushes for arms, paint brushes for legs. I’ve got food on this airplane. We got hours ahead of us. You got a lifetime ahead of you. Take whatever you want.”

I didn’t eat then. I was thinking about all the famous people at the funeral. Half of Hollywood, Big Jack had said. It seemed to me all of Hollywood. Hundreds of men and women. I crossed my bony legs. I wasn’t going to eat now, either.

“Uncle Jack,” I said, looking a little pointedly at my watch. “I can work for another half hour on the Renoir. You didn’t want to talk to me about my diet. Is there something else you intend to tell me?”

“Yes, Saulie, there is. It’s about an injustice. Something I want you to help me with.”

He was cutting his meat with his elbows out. Daumier, not Ingres. It had been the work of years, transferring my love for my father to him. “I hope I can help,” I said.

“I know you can. What I hope, Saulie, is that you will. It’s about a relative of mine who is also a relative of yours. You don’t know her she’s so shy. But you’ve met her in the flat. Fleeting by.”

By flat he meant the entire floor of the Battery Park building. I couldn’t think of the person he meant. When I got to the city I went straight to Hotchkiss. And then, when I was 18, straight to Yale. Wasting your time with your art and art history, is how he put it. But he paid the bills.

I ate my Aunt’s meals often enough, and had my own room whenever I wanted it. The Statue of Liberty was outside my window. I looked at him across the wrought iron table: “I didn’t know we had relatives here or anywhere else.”

“In this country she’s the only one, a distant one, now that Stanley and Rosemarie are gone. Her first name is Sonya and her last name is Kakzanov. Her family had had enough of life in the city of Tashkent. That’s in Uzbekistan, where there used to be a lot of Jews. They came here, I don’t know, maybe 15, 16 years ago. With three boys and a little girl. You are looking at the sucker who pulled a few favors and set them up in Forest Hills, though I never met any of them before in my life. Their skin is dark like walnut shells. A million-dollar house with a yard. Forest Hills is filled with their kind. I guess it wasn’t good enough; I don’t think a penthouse at the Plaza would have been good enough: because later on, I’m talking three years ago, they wanted to go back and go back they did.”

The tea in my cup and the tea in the teapot had gone cold. Somehow my uncle knew this; he raised a hand and magically everything was replaced, hot and steaming. “But not the girl. By then she had graduated from high school and she had this bug in her brain that she wanted to go to learn to be a cook. Don’t ask me why. So I said OK, I’ll send you up to Hyde Park where all those great chefs came from. But she said no, she wanted to go to this French place down in SoHo; this was about the time your Aunt started to get the disease, you know, her mind, and stopped cooking. What a convenience to have Sonya as a sort of companion for her and also she began to help out in the kitchen as, what do you call them?”

“A sous chef?”

“I think so. I think that’s it. So what I was paying out to that culinary place was not money down the drain.”

I tried to remember if I had seen the girl, after all. Dark skinned? No one came to mind. “Did she eat with us? At the table? You say she’s a member of the family.”

“Very distant. On the edge of the family tree. I asked her more than once. But she liked to be in the kitchen. She liked to stand by the wall in her apron. With her hands behind her back. Maybe a custom in her country. By the way, you ought to go out to the home. Trumbull. Connecticut: it’s not so far away. See Aunt Henrietta. I think she knows you even if she doesn’t know me.”

I put my napkin, linen of course, on the table. I started to rise. He shook his head and—those harness strings—I settled back in my seat. “You can wait, Saulie. That girl in the painting isn’t going to wake up and run away. And I want to get to the point about the poor girl I’m talking about.”

Uncle Jack didn’t know it, but he was quoting Matisse about the joy of art: that no matter what the frustrations in a painter’s life, whatever the sufferings and privations, when he returns to the canvas the sunflower will stand before him, just as he had left it, awaiting completion. Across from me, the big man was eating a french fry with both hands, in the manner of a panda. I felt, unbidden, one of those twitches of sympathy. No, the girl in the painting was not going anywhere.

“Here is the unhappy part. She’s not a citizen, Sonya. And you know what the spirit of things is nowadays. They are coming for her. I think she has fallen in love with the country. She didn’t want to go back when her family, all of her brothers, did; and she doesn’t want to now. She is, well, she is a desperate person. Of course I already made a few calls. I know Donald from business. I thought though I know you won’t believe it that he was a nice enough guy. Do I think he believes the stuff he says and the stuff that he is doing? Well, maybe in talking half the country into it he talked himself into it as well. Like in a mirror. Wherever he looks he sees himself. I don’t know: My calls weren’t answered. Or I got the bureaucrats. So this poor girl has to turn herself in. I’ve grown to have some feeling for her. I’ve gotten a taste for the soup she makes me. It’s green like a pea soup but there’s bones in it. Also of course I feel for her plight.”

“I can understand why, Uncle Jack. You’ve got, and you won’t believe it, either, a good heart. But what has it got to do with me?”

“Don’t play dumb, Saulie.” Uncle had a fork in his hand. He pointed the tines in my direction. “You’ve got to marry her.”

Four days later, on a park bench, I sat waiting for Sonya Kakzanov to come into view. Oh, I’d laughed out loud, all right, when Big Jack had made his ridiculous remark. But it was no joke. “Look, young man,” he’d gone on. “I don’t ask any questions. You live your life the way you want with zero interference. Except of a beneficent kind: All that tuition money, Hotchkiss and Yale and the soft job I got you in what do you call it, the curating department. So you don’t have to hang around some fag bar in the village. All right?”

“Uncle Jack, I don’t think you under—”

“Not another word for just a moment. I want to finish what I have to say. It can be a paper marriage, if that’s what you want. You don’t have to kiss her on the lips or on her body. This used to go on all the time. How the hell do you think half the Jews got into this country after they lived through the big war? You think I am uneducated. That I am not a sophisticate. What if I told you I read a book of Mann, the big writer. Well, I did. And I happen to know for a fact his daughter married a fruit poet she never even met, so she could be safe from the Germans in England. She ended up in Hollywood, practically across the street from the house you grew up in. Hollywood! This shit goes on all the time out there. Take another look at all those actresses and actors at the funeral. Smiling and smooching. Look up in the dictionary lavender marriages, okay? It goes all the way back to Valentino. What I am telling you, you don’t have to get up on your high horse.”

He paused. I managed to sneak in that I never thought he was uneducated. Beneficent. Fleeting. Conflagration: not the language of an ignorant man. I also sneaked in another word or two: that this whole idea was preposterous. And why didn’t he get his pal Donald to do it? He didn’t blow up. To my surprise, his eyes, deep set and dark, got misty. He reached across the table. He took my hand. “Listen, little Saulie, do me this one favor. At least meet her and have a talk and then you make up your mind.”

The girl was late, and the day was hot, hotter than when Uncle Jack and I were on the Shimonov Terrace. The newsprint of the Times was coming off in my hands. A quarter hour late. Then half an hour.

I had looked up the name Kakzanov. Aside from the bullshit, the Talmudic numerologists and their ilk, what made most sense was kok zan, a skinny woman. And that’s how I pictured her—slight, furtive and dark of skin: more a Gypsy than a Jew, maybe with a Gypsy’s golden earrings in the lobes of her ears. But the girl who finally approached me across the lawn was big-boned and pale. Her face was half-hidden by her tumbling hair. She stopped some six or seven paces away, and, in the manner my uncle had described, with her hands behind her back. A servant against a wall.

“Sonya?” I asked.

Just perceptively, she nodded.

“Would you like to sit down? It’s all craziness, isn’t it? But I am glad to meet you.”

“Yes,” she said, but in the hum of the distant avenue I could barely make out the word. She did not take a single step toward me.

“Well, I said, “if the mountain won’t come to Muhammad ...”

Then I was overcome with embarrassment. Not because the comment was lame, as it certainly was, but because this large, full-bodied girl was, compared to me, an alp. Still, I walked up to her and put out my hand. “Nice to meet you at last,” I said.

“Oh,” she said, “it’s nice to meet you.”

Her wide lips, I saw, trembled. Only one eye was visible beneath the black waterfall of her hair; it was wide and—what kind of Gypsy was this?—blue. She pulled her hand back as soon as it touched mine. “You don’t want to sit?” I asked. “Would you prefer to walk?”

“I’d like that. I know a spot. I mean, a place I sometimes go.”

We started down the nearby path, and then, aimlessly it seemed, over the tired grass. “Out for a stroll,” I said. “Like an old married couple.”

She didn’t seem to hear. She was bent a bit, perhaps out of deference to me. I glanced at her now and then. She wore a light blue blouse with brown buttons and what struck me as old-fashioned ruffles on the short sleeves. Her round arms were ruddy, rosy, as if the shame of the moment had gone there instead of the chalk of her cheeks. Her skirt was blue, too, periwinkle, and hung well toward her ankles. I snuck a look at what I thought would be nurse’s shoes. A surprise: She wore sandals and the toes that peeked through were painted purple, as if some wilder part of her had just been crushing grapes.

“That’s a pretty blouse,” I said, largely from desperation. “The blue and the brown.”

“Oh,” she said, as if startled, “thanks.”

“Sonya, listen. I can understand if you don’t want to talk about this situation. I don’t want to either. It’s completely nutty, don’t you think? The two of us on this blind date?”

She was on my right, staring off at the sky and the jumble of the clouds. Had she heard what I had said? I could see nothing of her face. One half of one ear made an appearance through her hair, like a child peeking through a curtain.

“Do you know what this feels like to me? It feels like what happens in India. Or maybe it happens in Uzbekistan, too. A father or it could be an uncle says you have to meet this girl and it’s like an audition for a play or something. Thumbs up or thumbs down! And the next day they are engaged. Maybe even if the thumb was down. Other people decide. What a meat market, wouldn’t you say?”

I was prattling, surely out of nervousness, and didn’t notice that she had come to a halt. I looked back to where, large and lumpish, she was standing. I started to retrace my steps but before I reached her she said, “It’s not a blind date. Not for me.”

Her hands hung down inoperable at her sides. I resisted the impulse to take hold of one. We started forward. “I mean, I’ve seen you,” she said. “But you don’t remember me.”

“You mean at Uncle Jack’s? He told me you were a companion to Aunt Henrietta. And that, well, when she couldn’t any more, you did the cooking.”

Again, she didn’t answer. Was that ear of hers—there it was, taking its bows—actually functioning? I spoke a little louder: “I am sorry. I don’t think I saw you there. Or I don’t remember. It was very good of you to help my aunt. We’re all grateful for that.”

“I notice things. Your coffee. You always poured a single teaspoon of milk into your cup.”

I laughed. “Yes, it’s one of the few lessons I learned in college. One of the professors, his name was Laurent: That’s the way he did it.”

“And your napkin. When the meal was over. Your uncle’s would always be on the floor. I didn’t mind. I suppose you could say it was lovable. It didn’t want to be on his lap. But you folded yours. Into a triangle. It could have been a handkerchief. Like the rich men wear in Tashkent. With the tip out of the breast pocket. My father wore that here. In Queens. My father—”

She stopped, as if the string of sentences had run her down.

“Yes,” I began, since someone had to say something. “Your father. And the rest of your family. I want to say I am sorry for the way they abandoned you. I wish I could help. I mean, apart from Uncle Jack’s crazy idea.”

“They didn’t,” she said.

“What? They didn’t what?”

“I abandoned them.”

“Oh. Well, I guess I know what you mean. You wanted to stay in this country. To finish your cooking school.”

She didn’t reply. This time I was content to follow along in silence as she lumbered toward the top of a slight, dusty rise. Always one. Never two, Laurent used to tell me. I suppose I was going to dutifully obey through all the coffee cups of my life. And the napkin? Like a dandy’s handkerchief? I thought of his precise coverlet, and then of his sheets, angled down: a dogleg, an elbow. In the hockey rink, the figures he made. Like a formula on a blackboard.

“See?” said Sonya, pointing off toward a small, leafy glen. The little ruffles near her shoulder flattened and then rose in the breeze. “I like to go there sometimes.”

That’s where we headed. Nearby, a child chased a dog. A group of boys were pulling on the string of a kite. We could hear it snapping above us. Three joggers off to our left. Also to the left a man kissing a woman up against a tree; his leg inside of hers. Then, quite suddenly, all of humanity seemed to fall away. We were in shade.

The grove we entered was small—this was, after all, Central Park—but after a minute or two we might have been walking in a forest. The tops of the trees closed over us. The smell of resin rose in the air. Gnarled roots seemed to grab at our ankles. Sheaves of grass, tall and almost black, rose from damp corners. The ground was covered with leaves, from which hundreds of ferns poked like—well, like the triangular tips of handkerchiefs; they were bright green in the occasional shafts of sunlight.

I called ahead to where Sonya, the bulk of her hips swaying, turned one way, then another. “Are you lost?” I cried.

“Oh, no. I have bread crumbs!”

The transition from the city, not far away, on all four sides, was so startling that one could almost imagine, behind the next tree, or the one after it, a gingerbread house. Sonya was reading my thoughts. “It is like a fairy tale, isn’t it?”

“Amazing. You can’t hear a thing.” That was true, the wind, moving through the tops of the trees, made a constant whirring, like a machine to drown out sound.

“I can,” she said. “Many things ...”

She motioned toward where a branch had fallen against the trunk of one of the largest trees: A horse chestnut? An oak? Don’t ask me. It made a kind of bench. She sat on it. After a second I joined her.

“What? It all seems quiet to me. We’re cut off. Like in a giant bell jar. A green one.”

“This is where I come. You learn to hear the things that are crawling. You hear what is gnawing on leaves. The tree trunks are always creaking and cracking and groaning; they have a hundred complaints.”

“Because they are a hundred years old.”

“Do you hear that? The bird?”

I did. Overhead some robin or raven or swallow—again, a kid from the coasts, I had no notion—was going, pee, pee, pee.

She lifted her head to listen. “He’s saying, I see you. I see you. I see you.”

Pee-pee-pee.

“But you can’t see me. He’s laughing at us.”

“Do you know the language of birds?”

“I am better at the language of trees. These trees. They are always murmuring.”

I laughed, like the invisible bird. “And what are they saying?”

“They are saying, ‘Is that our Sonya? A shy girl. A shy girl. A shy girl.’ Don’t you hear them saying that, Saul? ‘And this boy. This boy and this girl. What are they doing here?’”

I gave a start at the sound of my name. “Well,” I replied, “they are asking a good question.”

Her face, from the start, had been hidden by her hair. I saw her in fractions: one eye, an eyebrow, an inch or inch and a half of the flesh of her cheek. The constantly trembling lips. Now she turned toward me and with both hands gathered the strands and pulled them aside. Even in this sifted light her eyes were startling: the blue iris, like cobalt on Chinese porcelain. The nose was wide, the nostrils flared. Her throat was full.

Pee, pee, pee, went the amused bird in the treetops above us.

“Will you marry me, Saul?” Sonya said.

I could not help myself: I jumped to my feet. I wanted to run. But where? It did not matter: any direction. I thought my heart was pounding like a jungle drum. Then I did run, but a tree stuck out a root, as if it meant to trip me. I stumbled to my knees. I looked up. The whole forest swayed above me. High in the wind I could hear the leaves and branches, the crowns of the trees: muttering, mumbling, murmuring—Get up. Turn around. Look at the girl. She’s waiting.

I obeyed the commands. Sonya had not moved. She still sat with her dark hair gathered in her hands. Her face, her throat, the cotton of her blouse, all glowing. I retraced my steps and sat once more beside her.

“Yes,” I said. “I will.”

“You won’t have to touch me.”

Her eyes, I realized, were always staring; they never seemed to blink. It was as if her mouth, constantly aquiver, had taken on that task as well. Now, however, both lids fell shut, so that without looking at me or the world around us, she said. “Not if you don’t want to. Not ever.”

But I did want to. I put my hand on her soft cheek. I kissed her. She undid the row of brown buttons. Her breasts tumbled into my hands. How did our clothes come off? It was as if a wind had whipped them away. “Oh, my. Oh, my.” That’s what Sonya kept saying. Her back arched against the damp earth. The hair beneath the full rise of her belly was as black as a tuxedo. The heels of her feet, with those frenzied and delirious toes, the color of plums: They dug into me; they guided me to the deepest shade.

The comedy of attempting to carry my bride over the threshold. “Oh,” she said, when I put her down, “you have an atelier.”

It was much too fancy a word. What little sunshine that came into the room was, alas, from the north; but it was enough to light up the trays of apples on the table top, the half-filled glasses of wine, the lemons, the grapes. I’d never been more than a hobbyist, sticking to still lifes and copying the nudes that hung on the walls of museums. I had dared, once, to ask Laurent if I could paint him in the flesh. He cried out, “Mais, non! Regardez les femmes de Picasso. C’est la mort do’amour.” He pulled up his cravat and stuck out his tongue.

Sonya stood staring at the blemished masters I’d hung on the walls. Then she took off her wedding gown, which in truth was nothing more than a summer frock, and her underthings. It had nothing to do with l’amour. She wanted to pose for me—or this maidenly girl, an act of daring. I propped her on an elbow and gathered her hair over a shoulder. She was the Renoir I had yet to finish, though my odalisque floated on drapery instead of grass; the ballast of her buttocks pinned her down.

That was first of the series we did over the next few months. The experience only confirmed what I already knew: that I lacked the imagination of an artist. For each of these paintings—the hand over the crotch, looking in a mirror, or elbow on knee and thumb under chin—was a dim version of what hung in the museum of my mind.

It was during the third or fourth of these sessions that I realized Sonya was pregnant. Early on, I’d posed her as the Sleeping Venus, head in the crook of her arm and, as mentioned, hand over crotch. The belly, in both the Giorgione and in life, had a slight and suggestive rise. A month later she had swelled to the size of Rembrandt’s Bathsheba. and a month after that she could have become the fourth of Rubens’ Graces.

I had to work up my courage to ask the obvious. “Sonya, are you—are we—going to have a baby?”

She had developed, when speaking, a new habit: Her hands, her fingers, quivered in front of her mouth, as if she meant to filter her words. She raised them now. “Yes,” she said. “I think so. I mean, yes, we are.”

I said to Sonya, “If it’s a girl, let’s call her Daphne. She was the goddess who was turned into a tree.”

“I know, a laurel,” she said, though her fingertips were fluttering as if she herself were an aspen. “It’s a nice name.”

I called Uncle Jack that same night to tell him the news. His bellow came through the line with such force that I had to hold the receiver away from my ear. Then he calmed down and said, “You’re a fast worker, Saulie. You know what I mean? Maybe I was wrong about you. Your father! There’s a tear in my eye when I think about him. How proud he must be looking down from heaven. His name, Shimonov, it’s going to continue. I admit it’s my name, too. Maybe I’m crying for myself. Henrietta, I suppose you figured out she couldn’t. Her eggs. Her womb. I wonder in the depths of the night: Is that the burden that brought on her sickness? The disappointment in herself? What do you think? Saul, give me your opinion. Will this news be some kind of cure? An amelioration? I’m going to call her. I’ll leave a message with the nurses. Then I’m driving through the streets uptown to see the two of you.”

It would not be his first visit. That occurred half way through an Indian summer afternoon. Sonya was lying back with her hands behind her head. Her cheeks, her breasts shone with sweat. She smiled Goya’s smile. After a half hour I felt sorry for her. “OK, my bota koz-im, let’s take a break.”

That meant beautiful one with eyes like a camel in mangled Uzbek or Kazakh and was one of few ways I knew to make her laugh. Either because of my accent or because her eyes, so wide and blue, were those of a Siamese. She didn’t laugh. She didn’t move. The smile froze on her face. Her knees remained locked together. Even the rivulets of perspiration came to a stop. Those blue cat’s eyes stared past me, to where, I saw, my uncle stood in the door.

“Don’t worry about me,” he said. “I’ll stay here while the artist makes his art.”

“Big Jack!” I exclaimed, a name I had not used in years. “We’re done. Why don’t you wait for us in the living room? In the kitchen? Sonya, you can put on the robe.”

But he didn’t move. The bulk of his body filled the frame. The bota koz-im did not move either. She seemed like some other mythological figure, turned this time into stone.

“Sonya, sweetheart, you’re putting on weight. So is this dear nephew of mine. You shouldn’t be cooking for him. You should be cooking for me.”

I stepped from behind my easel and gathered her terry cloth robe. I stood so I blocked my uncle’s line of sight. This was the first time I had seen him since the day of our wedding. Five of us had attended the ceremony at the city clerk’s office. The bride and groom, of course; Jack; Aunt Henrietta, who had come in from Trumbull in a private ambulance and who spent most of her time smiling and nodding at Laurent, who had made the trip from New Haven in a resplendent maroon suit and whom—there was some kind of flower in his lapel—she must have thought was the groom instead of my best man. As for me, the artiste, I had to borrow a tie from the assistant clerk.

We waited there, on Worth Street, until they called our number. When I wasn’t sneaking looks at Laurent, the dimple in his chin, his hair slicked back like a comic strip count, I was struck by the other couples in line. Not that half the women were pregnant, but that the men and women looked as if they had already been married for years. Don’t they say that over time dogs and their owners come to resemble each other? A fancy lady, for example, and her Pomeranian. Do we, narcissists all, choose our pets and our mates because they remind us of ourselves? More likely, because the women are marrying some dream vision of their fathers and the men—well, for the same reason Oedipus chose Jocasta.

Not Sonya and Saul. Cousins or not, we might have been different species: her big bones and my small ones; her pallor and my indissoluble California tan; her stolid, staring, bovine features and my fretting and fidgeting, the sharp Semitic nose. No way could she have fit into that sporty MG.

Twenty-seven! They called our number. Uncle Jack came toward her. She clutched my arm with both hands. No blood flowed through that tourniquet. We looked at each other. The seas of her eyes! For the moment I shared the reverence of the Hindus for their quiet, guileless, sacred creatures.

After hearing the news, Jack started to come by more often, including Sundays when we did most of our painting. Sonya didn’t want to pose for nudes any longer. She said it was because she was ashamed of her body—the Sleeping Venus was well on its way to becoming the Venus of Willendorf; but I suspected it was because of the way Uncle Jack hung around like one of the spying elders in Tintoretto’s Susanna. Instead, she sat for me in striped skirts and big blue ribbons, like Cezanne’s wife.

My uncle paid for our flat. He had a key. He showed up whenever he wanted. Sometimes he’d be there when I got home from the museum. “I can’t tear myself away from this girl. Look at her. How can you leave her by herself? How can you live 10 minutes without her?” On occasion he stayed for dinner. He’d bring over all the ingredients—the marrow bones, blood soaked, in a plastic bag—or his favorite soup. “If she won’t make it for me at home, she can make it here.” One time he took her arm, led her to the couch, and forced her on to the cushions. He fell to his knees beside her and put his head to the knoll of her belly. He seemed to be listening through the layers of cotton.

“Pay attention to what I’m telling you, Saulie. Forget about that Daphne crap. This is a boy. I feel it in my gut. You want to name him for a Greek? Name him for the king of the Gods. I don’t mean Jupiter. I mean the handsome one. Apollo!”

Sonya began to toss in her bed at night. In her dreams she said, “He’s coming!” I didn’t know if she meant the baby, months early, or Uncle Jack. One night I heard a crash in the kitchen. She had dropped a dish. When I came in she was shaking. “He plays with me,” she said. “With my hair. He touches my cheeks. Can you do it?” she asked. “Will you do it? Tell him: not any more.”

I went down to Battery Park City to try. Jack insisted that we meet outside, though there was snow everywhere and the wind from a recent storm had not died down. I wasn’t dressed for it. Jack had a puffy down coat and a hat with flaps. His moustache, in the weak winter light, seemed painted on. We went toward the water. The spray that dashed up from it seemed to freeze in midair. “This is nature,” said my uncle. “It’s tempestuous. I wanted to come down here. It’s where I want to hear your bad news.”

“There’s no bad news. It’s just Sonya. In her condition. The way she looks. She needs her privacy. Maybe it’s best if you don’t come around for a while.”

“The cunt!”

I pretended that, because of the wind, I didn’t hear him. He brought his face closer. “It was supposed to be a paper marriage, right? Lavender, like Rudolph Valentino. I was happy that Sallie brought the faggot to the wedding. Wearing his flower. It confirmed for me what I thought. Flower boys. A boutonniere. But, no. But, no. You come down here and you tell me she doesn’t want to see me.”

“I didn’t say that, Uncle Jack. I only—”

“Why don’t you go back and tell her that I jumped in the water? Why don’t you tell her you saw me disappear beneath the waves? Then you can go home to the French food she makes you, and she can spread those fat thighs, those white legs, and you, you fucking tadpole, can lie down between them. I knew what you were going to say. That I was being cast aside. I wanted to make you say it down here. Where we are tiny. Where we are humble. Do you understand my meaning? We’re molecules. The wind can blow us away.”

I was, at these histrionics, speechless. He, with his black moustache, was a vaudevillian. Playing King Lear in the storm. Then, surprisingly, he put his arm around me.

“Don’t pay any attention. I am fond of that big cow. She’s family. What you heard: My feelings got hurt. Newlyweds: You should be alone. I won’t come around.”

Nor did he. Not for the next couple of months. Then one night, rather at 2 in the morning, Sonya shook me awake. “The key! Do you hear? The key in the lock!”

I sat up in bed. “No. It’s the rain, It’s hitting the windows.”

“You think I’m dreaming. I am not dreaming. He’s here.”

And so, I discovered, he was, dripping, leaving a damp lane behind him as he moved toward where I stood in my wrinkled pajamas.”

“I’m sorry. Sorry. You have to excuse me,” he said. “I was in the neighborhood ...”

His voice trailed away. He stood stooped, hunched, in his own little pond.

“It’s OK, Uncle Jack. I’m going to make you a cup of coffee. And I’ll get you some dry clothes.”

“It’s nothing. Nothing. April showers. I didn’t bring anything. Can you forgive me? No bones. Lamb bones. Lamb ribs.”

He was swaying. I took his arm, but he shrugged it off. “Just walking by, you know. I thought I wanted to be here. I had a thought. It was a premonition.”

“Of what? It’s 2 in the morning. Are you all right? You should change. You can have the couch. You can stay the rest of the night.”

“No, no, Saulie. I’m going. I was wrong. I didn’t calculate right.”

He stepped away. He turned as if he really meant to go. Then I heard a cry from the bedroom.

“Oh, Saul! Oh, come!”

She was sitting on the edge of the bed. Something, like a stream of urine, was pouring over her legs. “It’s the baby!” she wailed.

I wrapped the blankets around her. We hobbled together into the lobby and toward the front door. The impediment of Big Jack was still standing there. We moved around him. A red curtain had fallen over my eyes. I wanted to stop and raise my fists. I wanted to roar at him, You killed her! You killed our baby! But I guided my wife out into the hallway and toward the elevators without saying a word.

4.

Jack was right. About his premonition, about Daphne being the wrong name, about everything. I thought that, at seven months, we had lost our child. In fact, Sonya gave birth to a boy; we called him Stanley. I thought he would have to be in Lenox Hill for weeks, maybe months. But he came home, his tight fists flailing, three days later. My uncle wanted a big celebration at Battery City, but we settled on letting him have the bris there, in his cloud-high apartment.

Henrietta would not take the ambulance. I said I’d drive out and bring her in. It wasn’t that much farther to go to New Haven, so I picked up Laurent. He thought the ceremony was une acte de barbarie. His own penis, I remembered, muscular and curving, had been spared the knife. My aunt perked up when she saw him. It might have been the flower in his lapel. She insisted he sit with her in the back. Did she know which one of us was her nephew? Somehow her hair was now orange instead of white. She would not let me wipe the spot where lipstick was smeared on her cheek. In the rearview mirror I saw the various expressions that crawled over her face. She seemed intoxicated from the cologne worn by the professor of French.

A score of people waited for us up on the 43rd floor. Big Jack had decided to put on a bash. His real estate pals and their wives. Maybe it was his idea of having a minyan. The men had drinks in their hands. Most of them were bald with horseshoe fringes. It was like a cartoon: moguls at play. A lot of them came up to me and shook my hand. I wasn’t Sallie any more. They kept shoving cigars into my pocket. I looked around for Sonya, for Stanley. Not in these big rooms surrounded by glass. I went over to a little man sitting with his knees pressed together. It turned out he was the mohel. He wore a business suit with an open collar. I supposed in my fantastical mind he would be wearing scrubs with canvas over his shoes.

“OK, OK, everybody!” That was Uncle Jack, banging on the side of a glass. A miracle it did not break. “My dear wife, Henrietta, has arrived. All of you know her and have affection for her and want to raise your glasses in her honor.” In response, a half-hearted cheer and up went the tumblers of Scotch and soda. My aunt sat slouched in a large chair. She nodded and lifted one hand. “We couldn’t begin without her and now we can. It’s an important occasion. It goes back to the time of Abraham. We can laugh and scoff and behave like Philistines and who can say there is not a lot to be ashamed of in our daily lives; but this is still a covenant with God and it makes a Jew a Jew and for this moment while we have this innocent babe among us we can believe and behave in a way that we are going to rejuvenate our souls. I mean, you know, make us inside as young as him. Which is all I want to say.”

Polite applause. A laugh or two. Laurent looked over at me with a kind of Parisian knowingness; but I turned away. Insane how I let this big man, with his black moustache, endear himself to me.

A gasp, then clapping. A nurse, or a nun—anyhow, someone in a white uniform with winged white bonnet—came from the hallway with Stanley in her arms. He seemed fast asleep. Sonya, wearing a cap and an apron, came just behind her. The crowd buzzed around. The baby, with a wrist curled under his chin, was borne through the air to where his grandmother was sitting. They put him down like royalty onto the purple cushion that now lay on her lap.

Then, quite suddenly, all of humanity seemed to fall away. We were in shade.

The little man in the brown suit now rose. He said a prayer to the King of the Universe and then, with his shield and his tube and his knife he got down to work. I saw Laurent, the blood drained from his face, leaning against a window frame. Henrietta smiled her vacant smile. What had transformed her? To me it seemed overnight. When I stayed over, between semesters, during the summer, she used to read Proust in French. We had a running debate about whether the portrait of Madam Verdurin had any geniality in it. Yes, said I. Pas du tout, said my aunt, who thought Proust the most ferocious of men.

In the midst of these musings—anything, Proustian or plebeian, to distract me from what was happening to my son—a cry rang out. The weak howl of a babe, but I was certain it could be heard by the men and women on the pavements a hundred miles below. Involuntarily I took a step forward: Barbarie! Police! Au secours! But I stopped myself. Where was Sonya? How could she let this happen? But I knew where she was. Dragooned, the poor girl, into cooking the tyrant’s feast.

And as soon as the prayer to bless this tender infant was intoned, Big Jack invited us all to that very banquet. The dining room was lit by three chandeliers and the lesser light that came from a row of high windows. The table was set with burning candles and what seemed a silk tablecloth. The wine glasses were rimmed with gold. My uncle sat in the middle, with a strange man on his left and a strange woman on his right. Henrietta sat across from him; Laurent was at her side. “The first thing we’re going to have,” Jack announced, “is my soup. Shurpa soup! You’re going to taste it. It makes you strong! It straightens your spine! Oh, the smell of it!”

With those words the kitchen help came out—in waves it seemed. They each carried a bowl of the soup, steaming, the color of verdigris, with bones sticking out of it. Sonya came out at the end and set the last bowl before Uncle Jack. “Ah! The chef! My darling Sonya! This isn’t from her fancy cooking school. This is Uzbek! From the Caucasus. From Asia! The real thing! She’s a true Shimonov. A Shimonova! My blood is in her veins!”

Jack raised his hands and clapped. The crowd joined in. Sonya, ever bashful, hurried back to the kitchen. We picked up our spoons and dug in. There was some conversation. A joke of some kind made its way round the table. But what you heard mostly was the sound of sipping, slurping; people dabbed with their napkins as the grease ran on their chins.

Suddenly, Henrietta, old and frail as she was, got to her feet. I thought she had recovered herself; I thought she was going to make a toast. But there was no glass at the end of her extended arm. She was pointing at the man across from her. “You!” she declared. “You! You did it to her! With the blood in your veins!”

She sat, collapsing. A silence—only a second or two, but it seemed like a century, an epoch.

“What? What?” That was Jack. He half rose from his seat. His napkin fell from where he had inserted it into his collar. “What?” he said for the third time; and then the thick green broth flew from his mouth. For a moment he hung there, the knuckles of both fists on the table. People were rising, their chairs clattering backward. Two women started to flee from the room. The bald men moved toward Jack. He remained as he was and then—it was horrible, like a scene in the corner of a Hieronymous Bosch—the soup spewed from his mouth again. After that he fell face forward, and with a sound like a detonation collapsed on the table.

Now all was a chaos of shouts and screams. People were yelling into their cellphones for help. Men rolled Jack onto his back. I saw his tongue hanging out. Someone was pumping his chest. Every glass, I saw, lay overturned on the table. The upended candlesticks sputtered and went out. Laurent came and took hold of my arm. I shook him off. I started to move toward my uncle. But the man who had been pushing on his chest stood up. “His heart,” he said. “It’s stopped.” A wail went up. The guests raced every which way. They wanted their coats and their hats. And then, in the center of all the quick movement, among the white faces, I saw Sonya, with her apron around her waist. She stood against the wall with her hands behind her back, quiet and modest and unmoving. She stared with her wide, blue eyes at this garden of earthly delights.

Late that summer, when the leaves had started to fall, we went back to the little grove. Stanley was with us, carried in a halter. We found the same branch, fallen against the trunk of the same tree, and sat there awhile. What happened after the bris of our son? Not as much as one would think. There was no autopsy on my Uncle Jack. No inquest, either. No one thought to take a sample of the Shurpa soup. It turned out I had another uncle, Manfred, who had some kind of farm in Manitoba. A black sheep, it seemed. He made no fuss. He took the surprising amount of money that had been left him. A stopped heart, the guest had shouted: case closed.

I had not yet picked up a paint brush. I did do a series of sketches, nothing but pencil: Stanley asleep. Stanley with his stockinged foot in his mouth. I thought that soon I might do a portrait of my wife: Could I, through her clothing, while at her tasks, capture her big, slow-moving bones? We did not talk a great deal.

We were silent in the forest, as well. The fronds, the ferns, the mosses, the green blades of grass: They crouched in the shadows or reached toward the fitful rays of the sun. The air around us was the color of cinnamon. Above I heard the cry of what seemed the same bird: Pee, pee, pee. He’d returned from wherever he went in the winter; or perhaps he’d stuck it out through the snow, the gales.

Pee pee pee.

I’m back. I’m back. I’m back.

Pee pee pee.

You’re back, too!

Sonya turned toward me. She said, “Do you hear them, Saul? The trees? What they are murmuring?”

I didn’t answer.

“You forgot. I’ll tell you. They—”

I held up my hand. I didn’t forget. I knew what she had said the year before. That she could hear the things that were crawling. The things that were gnawing. The fall of a pine needle, perhaps. I did my best to listen. A leaf swayed as it tumbled by me. Another leaf followed it. Then I thought I heard, however faintly, the same words myself: This boy and this girl. What are they doing here?

Sonya unbuttoned her blouse. The hungry infant took her breast in his mouth. He drank the sweet milk.

Leslie Epstein teaches creative writing at Boston University. His three Leib Goldkorn books were recently published as The Goldkorn Variations: A Trilorgy (no typo). His play King of the Jews runs from Oct. 28 to Nov. 18 at the HERE Theater.