At first glance the tapestry seems to show a charming country scene, the sort of nostalgic evocation of olden days that’s a folk art staple. The little white farmhouse is bordered by daintily stitched flowers and trees lush with appliquéd leaves. In the foreground, people in old-fashioned caps and shawls are setting off on an outing in two horse-drawn wooden carts.

But look closer. The people in the carts are wearing tiny armbands embroidered with six-pointed stars; they are the Jews of the tiny Polish village of Mniszek, being rounded up and sent to their deaths on a bright October day in 1942. Yet even as this horror unfolds, the setting—the rolling patchwork fields, the tidy barns, the leaves beginning to show their autumn colors—has the beauty of a wistfully remembered dream.

The picture was made by Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, whose family was among those who left Mniszek that day, never to return. At the last minute Krinitz, then 15 years old, decided to flee with her younger sister, Mania, to find a non-Jewish family who would take them in. In the picture the two girls are there, walking away past the little farmhouse, relegated to a corner while the drama of leave-taking fills the foreground.

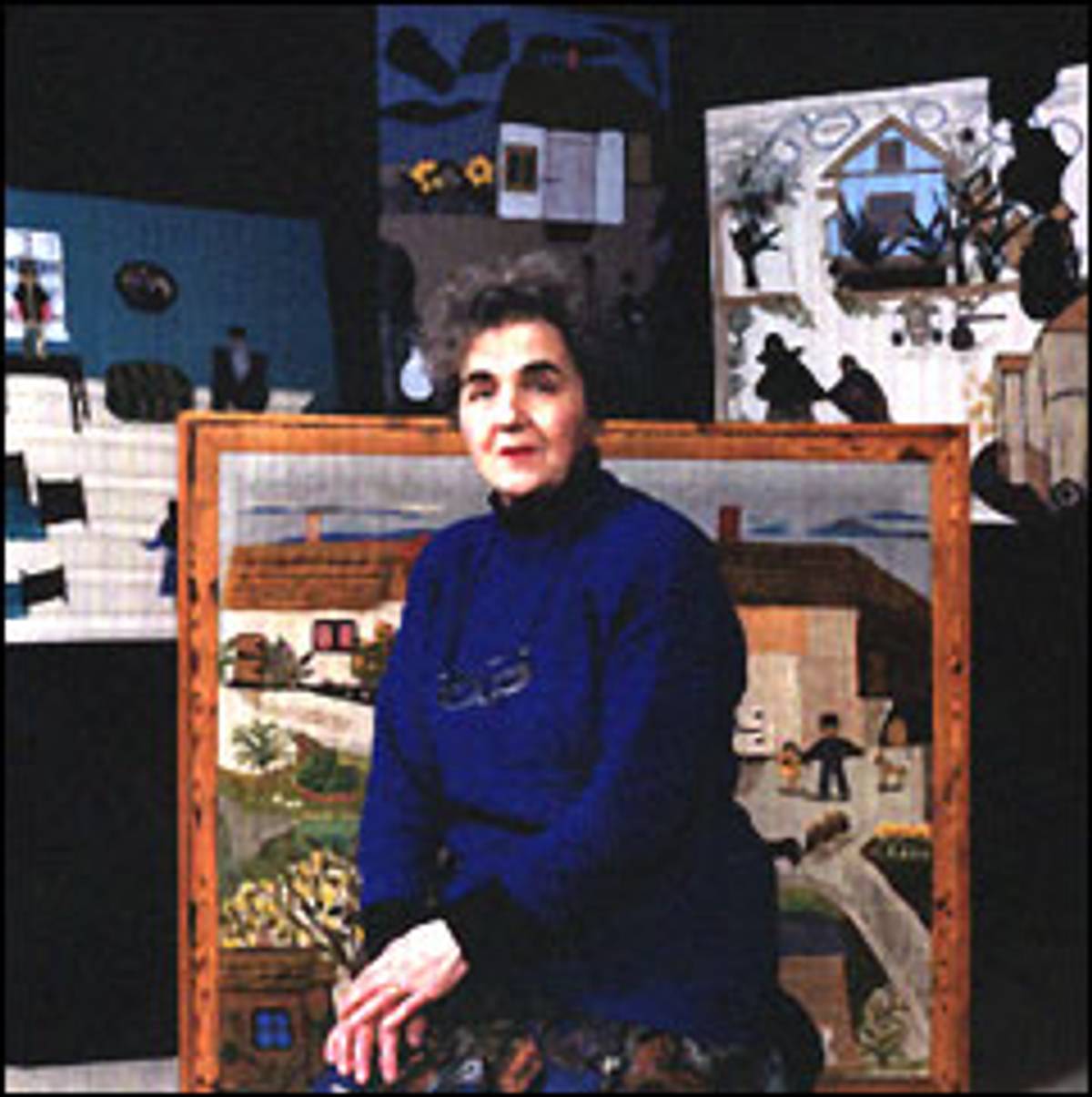

The work is part of a cycle of some three dozen exquisitely made fabric pictures through which Krinitz, decades later, sought to preserve the memory of her lost family and her own survival. A vivid record of one community’s destruction, the pictures are also much more, thanks to their deft use of color and artful simplicity. The entire cycle is currently on view through February 11 at the Judah L. Magnes Museum in Berkeley, California.

Alla Efimova, the Magnes’ curator, says that depictions of Holocaust memories by untrained artists like Krinitz are no rarity. But when she saw Krinitz’ fabric works in person she was overwhelmed by their power. “I don’t see them only as illustrative,” she explains. “Their craft and creativity and inventiveness are just as striking as their story.”

Krinitz and her sister survived by pretending to be Polish Catholics and working as farm laborers. After the war they learned that their parents, brother, and two younger sisters, along with almost all the other Jews in Mniszek, had disappeared into the Nazi death camps.

Krinitz married, emigrated to the United States, and raised two daughters. Trained as a seamstress when she was a girl, she became a dressmaker. As her children grew, she told them stories of life in Mniszek and what happened during the war. But telling wasn’t enough; she wanted to record her history in some more permanent way. She tried writing, but the results didn’t satisfy her. Lacking art training, she didn’t feel capable of drawing her memories either.

In 1977, when she was 50 years old, she decided to use her needlework skills to show her daughters her childhood home. She created two large, heavily embroidered tapestries, one showing the Nisenthal family, their house and barn and horse and geese, the second depicting Esther and her older brother swimming in the nearby Vistula River.

“She wanted my sister and me to really see what her home had looked like,” says Bernice Steinhardt, Krinitz’ older daughter. “She did those first two pictures and was really pleased with them.”

Around that time Krinitz’ first grandchildren were born, and Steinhardt recalls that her mother’s sewing energies were diverted to making things for the children. Perhaps Krinitz also hoped that portraying her family as it was before the war would be enough.

But about a decade later, dreams about her wartime experiences drove Krinitz back to her memory project. She began by depicting two nightmares she had had as a girl, after she left her family. In the first picture she and her mother are running away as black chunks of star-studded sky crash to earth. In the second, she visits her dead grandfather, who in her dream had told her, “You will cross the river and you will be safe.”

The two dreams both embody the terror of the war years and Krinitz’ longing for forgiveness from her family. Realizing them in cloth and thread pushed Klinitz to a new level of artistry and opened the floodgates of her creativity. The rest of the cycle poured out over the next ten years, until she became too sick to sew. Her last picture was completed in 1999; she died in 2001, at the age of 74.

Working with a mix of needlepoint, fabric collage, hand and machine embroidery, and fabric paint, Krinitz tells a story that begins in the idyllic prewar days of 1937 and ends with her arrival in New York in 1949. Some of the pictures document life in Mniszek before the Germans came: the women making matzoh, two patriarchs conducting a Rosh Hashanah service. Others, the majority, depict the gathering terror of the German occupation and the Final Solution. Several show Krinitz and her sister being turned away by non-Jewish neighbors too frightened or too callous to take them in. Most include hand-stitched captions elaborating the stories they tell.

As Krinitz worked, her confidence grew and her compositions became more elaborate. “I’m very struck by her inventiveness,” says Efimova. “A lot of self-taught artists find a formula and repeat it. She learned from herself and developed very sophisticated representational techniques.”

Krinitz returned to that October day when she said good-bye to her family in four different pieces created over an eight-year span. Each time she revisisted the scene, the composition became more powerful and the perspective widened. The first version, made in 1991, shows only Krinitz’s own family. The fourth, the picture with the two carts, completed in 1998, depicts the events as a tragedy for an entire community—even, perhaps, for the two Polish villagers whom Krinitz shows looking on.

“She was finding her voice,” Steinhardt says. “She was ready to see that day from the perspective of her parents and not just herself.”

Another picture, also from 1998, has a similar composition and likewise shows two vehicles full of people traveling along a rural road. But this one records something Krinitz saw as she made her way to Berlin with the Polish army after the collapse of the German Reich: a battlefield where dead German soldiers lay scattered on the grass and the bodies of Nazi officers, hanged by the Russians, dangled from the trees. Stitched in a dazzling array of deep greens and blues, it’s simultaneously beautiful and ghastly, evoking both relief and remorse, justice and sorrow.

One of Krinitz’ most formally lovely compositions presents a scene from early in the war. On the right side, in a field of densely embroidered grass ringed by flowers and fruit trees, Krinitz and her sister are pasturing a Polish farmer’s cows. But through the trees, on the other side of the picture, they can see a camp where Jewish boys are being worked to death hauling logs and digging rocks. A kapo wearing a Jewish star whips some of the boys, while a German soldier is about to shoot one who is no longer able to work. Both sides of the picture are extraordinarily detailed, down to the delicately stitched leaves of grass and the embroidered welts on the boys’ backs. Much of the picture’s impact comes from the clash between the pastoral scene and the torture occurring alongside, and between the beauty of the stitching and the hideousness of the story it tells.

Efimova points out that the rich texture of Krinitz’ work, almost impossible to capture fully in reproduction, is a source of its emotional power. “Her way of facing these memories was through this obsessive detail,” the curator says, “this displacement of pain into craft.”

For Steinhardt, her mother’s obsessiveness was about creating a record. “For her all of this was documentary,” she says. “My mother felt very strongly about it: This was exactly how it was. She didn’t want to forget anything. Otherwise her family would be lost.”

These articles are not currently attributed to anyone. We’re working on it!