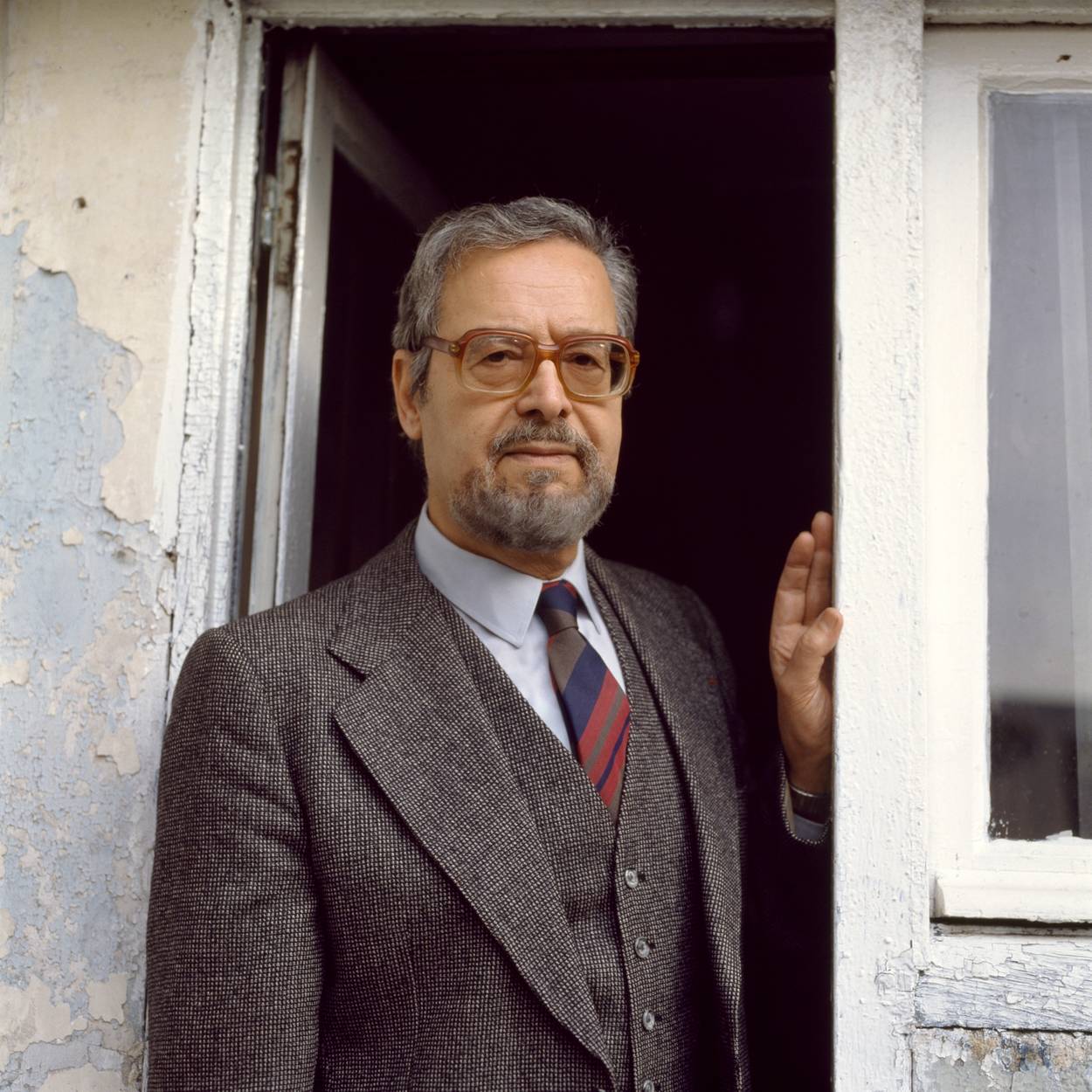

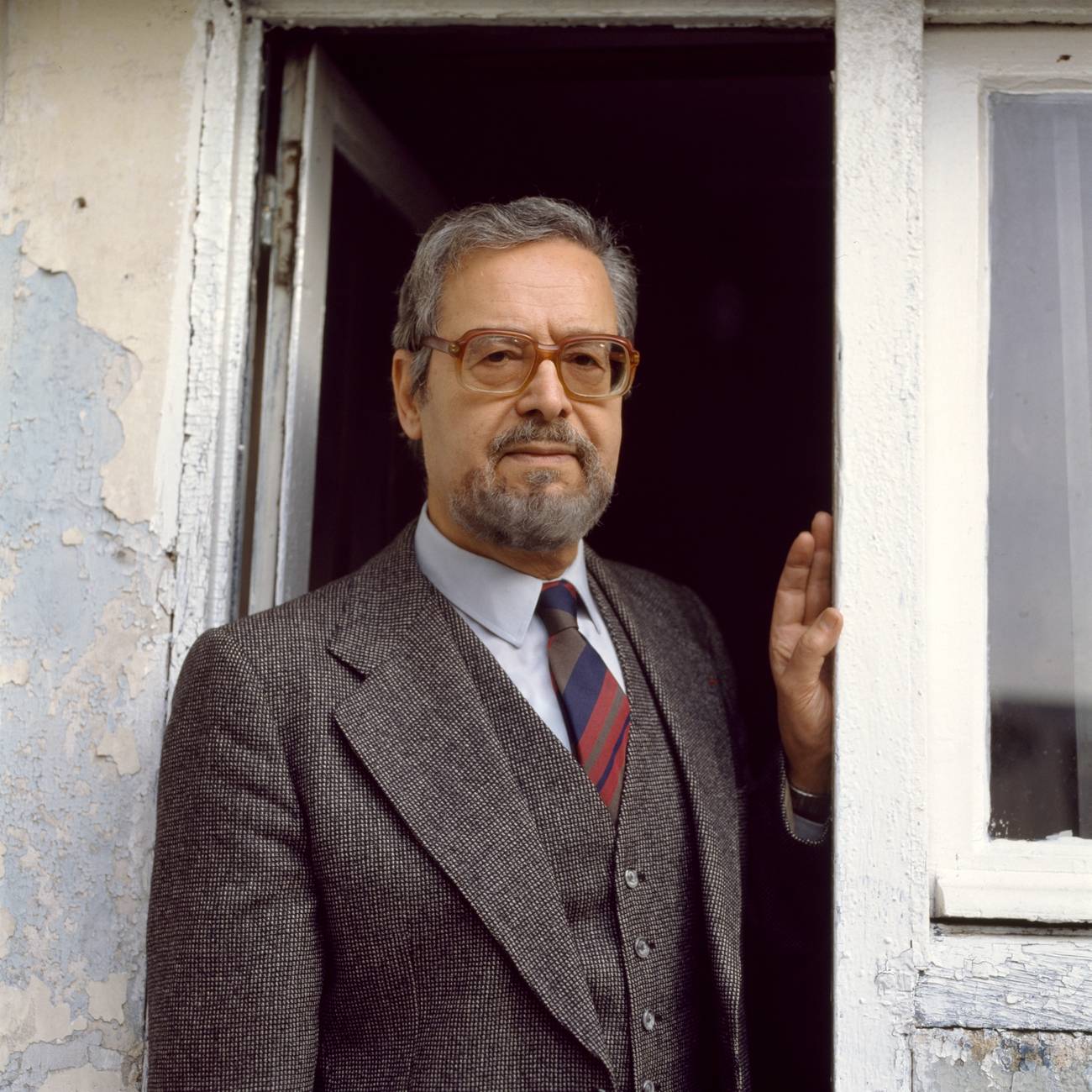

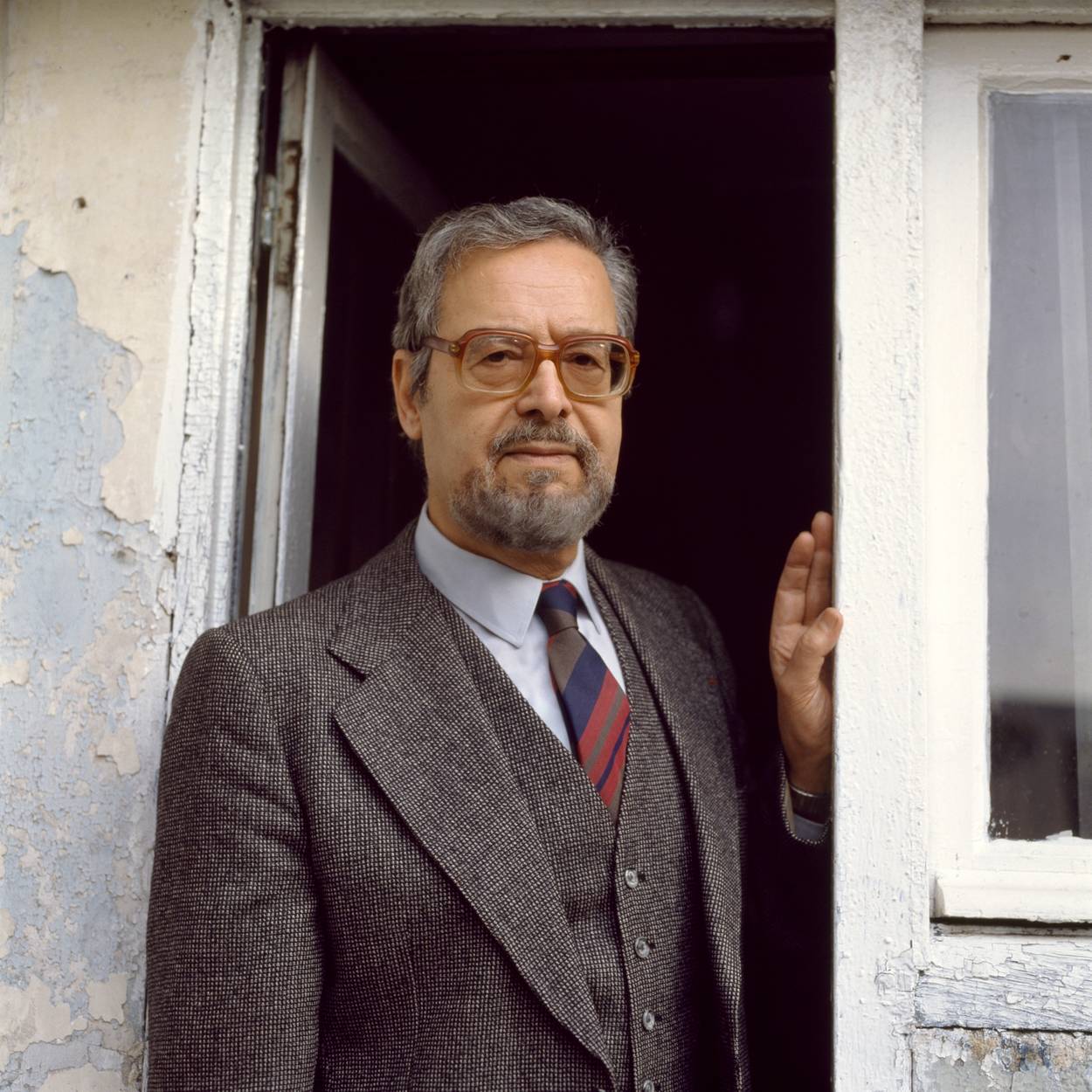

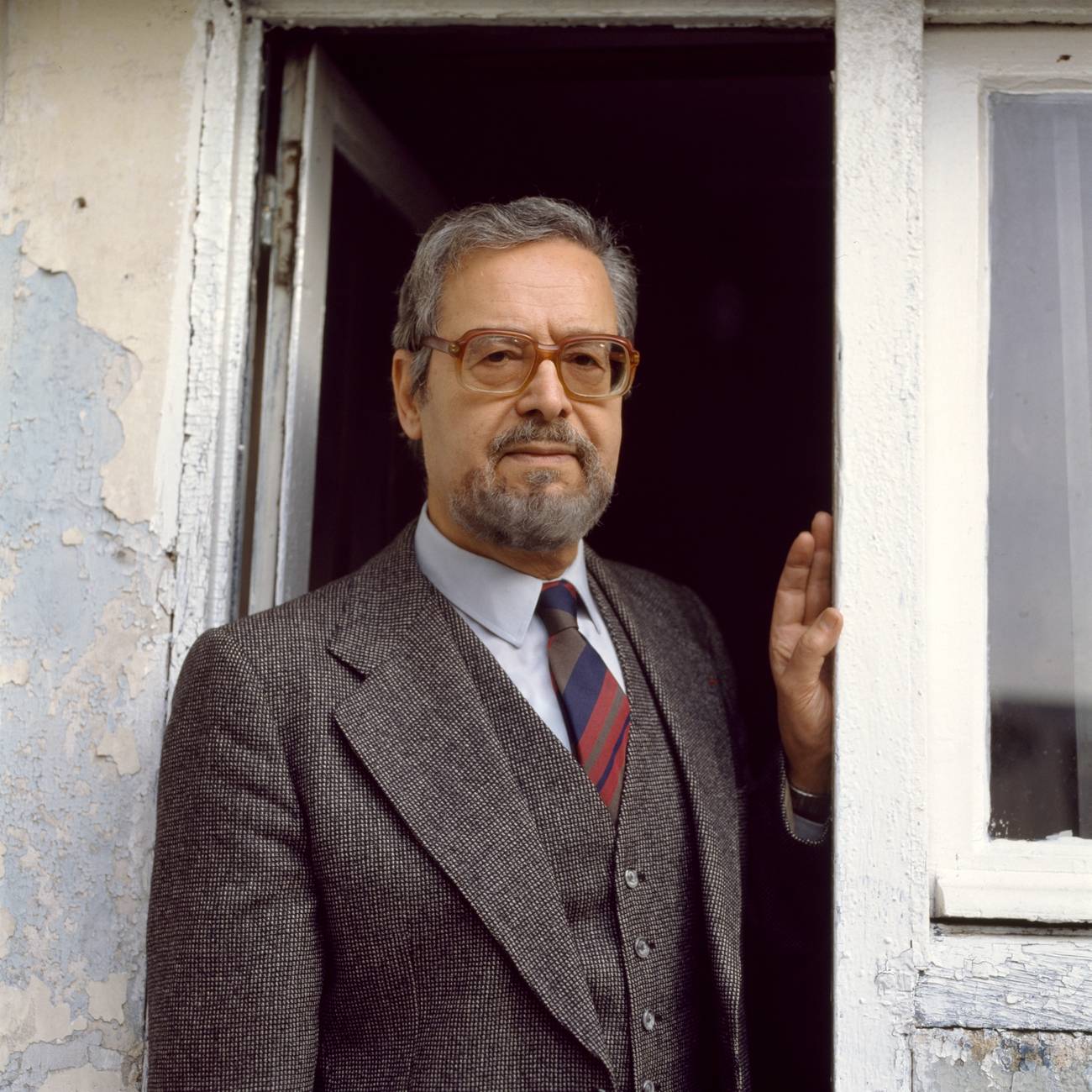

The Heresies of Albert Memmi

The Tunisian-born writer died in May at 99. He leaves a rich, important, and complicated legacy of colonial and postcolonial thinking.

Can you sit shiva for someone you have never met? I ask because I’ve been in mourning since learning that Albert Memmi passed away on Friday, May 22. When I learned the news, I was in the midst of working through the copy editing of The Albert Memmi Reader, available in December to celebrate Memmi’s centenary. The compendium condenses the library of one of the great heretical Jewish thinkers of the past century.

Memmi’s resistance to fallow binaries was woven into his cultural DNA. He was both Jew and Arab, Tunisian and French, African and European, born poor and yet privileged, Jewish but staunchly secular, a Zionist and critical of Israel, a leftist who highlighted the blindness of progressives, a prophet of national liberation whose viewpoint was internationalist. He died a socialist and anti-colonialist who was unafraid to highlight the failures of Third World postcolonial regimes.

Memmi is most remembered as the author of The Colonizer and the Colonized, published in 1957 just when the Algerian revolution was locked in the bloodbath memorably fictionalized in Gillo Pontecorvo’s film The Battle of Algiers. The book sealed the global reputation of a young writer, then 37. In it, he patiently showed how colonization rotted not only the colonized but also the colonial oppressor. To break the deadlock required a revolt that ultimately would free both parties from the chains that bound them.

Famously introduced by Jean-Paul Sartre, just as the French editions of his breakthrough novel, The Pillar of Salt, would be prefaced by Camus, Memmi was the last living representative of that suave generation of great existentialist thinkers living in Paris. Ultimately, he broadened their purview to consider how the dialectic of human recognition that figures so prominently in their work needed rewriting in a colonial context.

Memmi’s treatise on decolonization was about more than just the strictures of colonization. It is one of the great texts on the mot du jour on many college campuses: privilege. It established Memmi as one of the most insightful commentators on racism, a topic he rethought anew as “a native in a colonial country, a Jew in an anti-Semitic universe, an African in a world dominated by Europe.”

The words are those of Alexandre Mordekhai Benillouche, the semi-autobiographical protagonist of The Pillar of Salt. Published in 1953, it won the prestigious Prix Carthage, and established his literary notoriety. It was among the first major North African crossover novels written in French, helping to usher in a new generation of Maghrebi literature that went beyond the exotic, Orientalist clichés of earlier works by nonnative writers. Memmi would go on to write five other novels, books of poetry, and his famous sociological and philosophical essays.

Little presaged Memmi’s rise to intellectual fame as a French writer. He was born in the hara, on the edge of the Jewish quarter in Tunis on Dec. 15, 1920. The oldest boy in a large family, his mother was an illiterate of Berber background and his father was a saddler of Italian descent. The language of his home was Judeo-Arabic when he started to study Hebrew in his kouttab, a traditional religious school. Destined to inherit his father’s business, Memmi was plucked out of this destiny by his raw talent, which was revealed when he attended one of the Alliance israélite universelle (AIU) schools in Tunis in 1927 before being selected for a scholarship to Lycée Carnot, the most prestigious high school in Tunisia.

Two professors at Lycée Carnot, later fictionalized in The Pillar of Salt as Marrou and Poinsot, would profoundly influence him: Jean Amrouche, a renowned Francophone poet, and the philosopher Aimé Patri. While continuing his education in philosophy at the University of Algiers, Memmi began his own foray into the Republic of Letters, which was his true home.

The dark years of the Nazi occupation stalled his ambitions. After the defeat in June 1940, the French government moved to Vichy, passing draconian anti-Jewish legislation that systematically excluded Jews from citizenship and rights, and sought to eliminate Jews from public life. As a result, Memmi was expelled from school in Algeria and forced to return to Tunisia. The German and Vichy governments bombarded the airwaves with anti-Jewish propaganda, hoping to stir the Muslim population against the Jews. But according to the historian Paul Sebag, “manifestations of hostility were, in sum, rather rare.”

Following the Allied landings in North Africa in November 1942, the Axis powers directly occupied Tunisia, drastically altering everyday life. Tunisian Jews now faced pillaging, forced labor, and regular bombardments. Some 5,000 Jews were rounded up into labor camps, Memmi among them. But in May 1943, Tunisia was the first country with a sizable Jewish community to be liberated from Nazi occupation as the Allies moved from North Africa into Europe to end Nazi rule.

After the war, Memmi moved to Paris following in the footsteps of Amrouche and Patri. He enrolled at the Sorbonne to study philosophy with Gaston Bachelard, who would influence the generation of post-structuralists with his idea of the “epistemological break,” and with Jean Wahl, whose vanguard studies cobbled together the building blocks of existentialism. Nonetheless, for the most part Memmi found Paris depressing and his studies pointless. As was the case in Tunis, he became active in Jewish student circles, working to create and then edit Hillel, a Jewish journal, and immersing himself in the writings of Martin Buber, which he wanted to translate into French.

While living in the student dorms at Cité universitaire, Memmi met his wife, Germaine Dubach, who came from a Catholic family from Lorraine and was studying to pass her agrégation—a competitive national exam that would enable her to become a professor of German. They were married in December 1946. His marriage was a form of liberation, since it meant “freedom, outside the little community of my birth,” as he put it. The challenges of a mixed marriage later provided material for a number of short stories and Memmi’s second novel, Agar (Strangers), which would win the Fénéon prize.

In 1947, Germaine received a post in the bombed-out city of Amiens, where they moved. There Memmi began to work on The Pillar of Salt. In 1949, the couple returned to Tunisia where he took up a position at his old school, Lycée Carnot, then directed a center for psycho-pedagogy, and established himself at the heart of Francophone intellectual life.

In 1953, Memmi returned to France with the completed manuscript of The Pillar of Salt. Set in French colonial and occupied Tunis, it is a bildungsroman of Alexandre Mordekhai Benillouche. As Camus indicates in his preface, his identity is “riddled with contradictions.” Memmi’s protagonist is defined by his rejection of the constraints of his own family and upbringing, as well as his rejection by the bougi-Jews he meets at school. He forms friendships with young Arab nationalists who recruit him to the cause but who nonetheless harbor Judeophobic ideas. Both groups face the Vichy colonizer, wrapping together anti-Semitism and colonial racism.

As the novel unfolds, Alexandre comes to discover what Frantz Fanon explored in Black Skin, White Masks, published the year before Memmi’s novel. He learns that the quest to master French civilization alienates and separates colonial subjects from their indigenous cultures. But writing in French, “a terrible and marvelous secret,” as Alexandre calls it, becomes a leitmotif in his drive to self-realization, since it enables the character to define himself rather than be defined by others, even as he does so in a language that is not his own—a predicament that the French Algerian Jewish philosopher Jacques Derrida would perceptively analyze in his autobiographical reflection, Monolingualism of the Other.

A year after the publication of The Pillar of Salt, the Franco-Algerian war exploded. Immersed in the Tunisian nationalist movement across the border, Memmi served as the literary editor for the magazine L’Action, founded by Habib Bourguiba, who would become the prime minister of an independent Tunisia from 1956-1987. The weekly continues today as Jeune Afrique.

During this period, Memmi began more rigorously analyzing the colonial condition in North Africa. By the time Morocco and Tunisia gained independence in 1956, he had come to believe that the emerging Arab states had no place for Jews. This view was bolstered by the establishment of Islam as the official religion and by the Arabization of the educational system, followed by a set of decrees that made it difficult for Jews to make a living. He and Germaine became part of the exodus of Tunisian Jews leaving mostly for Israel and France. They settled permanently in Paris, where they worked at French universities until their retirement.

Memmi’s portrait of the colonized would first appear a year later in Esprit, a left-wing Catholic journal that published many of the great anti-colonial voices of the era, including Negritude poet and first President of Senegal Léopold Sédar Senghor and Algerian writer Kateb Yacine, both of whom appreciated his new work. The portrait of the colonizer, the other major chapter of The Colonizer and the Colonized, appeared in Les Temps modernes, the other great leftist journal of the Left Bank.

This was despite the fact that The Colonizer and the Colonized contained a lengthy critique of what Memmi called, “the Nero complex”: “the failure of the European left in general and the Communist Party in particular, for having underestimated the national aspect of colonial liberation.” Perhaps for this reason, Sartre, who was deepening his commitment to Marxism, penned his staunch critique of Memmi’s book, which would nonetheless henceforward appear as the introduction to all future editions. Even as he praised him for his insights, Sartre disparaged Memmi for his “idealism,” writing “[t]he whole difference between us arises perhaps because he sees a situation where I see a system” built on an apparatus of production and exchange.

But for Memmi, a Marxist analysis built on purely economic maxims missed crucial aspects of how colonial domination works. Colonization depends not only on profit and usurpation, but also on privilege. Memmi makes clear that privilege has economic, legal, normative, social, symbolic, and psychological ramifications. It determines who is hired and fired and into what positions, who governs the system of labor, and who benefits from that labor. It shapes the law and administrative structures so that they advantage some to the detriment of others. It defines the rules and norms of colonial life and the status of the inhabitants of the colony.

However, privilege is never absolute, Memmi believed. Instead, privilege is relative to “the pyramid of petty tyrants,” as Memmi calls it, whereby “each one, being socially oppressed by one more powerful than he, always finds a less powerful one on whom to lean, and becomes a tyrant in his turn.”

Memmi drew out this theoretical maxim by discussing the relative privilege of the Italians, Maltese, Corsicans, and Jews in Tunisia, relative to the Arabs and the French. Unlike those assimilated by the colonial power, Jews were colonial natives. But they were among those considered suitable for assimilation, unlike the Arabs.

Without understanding this pyramid of privilege—the differential treatment of Jews in the colony and then their different experience back in the metropole following their migration—you cannot really understand the dynamics between Jews and Muslims living in France today. Some of the colonized are always accorded certain privileges relative to others; this is what makes the machinery of subjugation run. Memmi’s diagnosis of privilege thus clearly indicates that he situates the individual and social analysis of colonization within a structured system of relative privilege that underpins the racial order in the colony and that continued in different form into the postcolony.

If the system of privileges is the core of his portrait of the colonizer, then central to the portrait of the colonized is how they navigate both the discourse and structures of colonization. Colonialism establishes cultural dominance through what Memmi terms “the mythical portrait of the colonized”—the stereotypes that legitimate colonization, which are wound into the educational system and the institutions of everyday life and come to shape the self-image of the colonized. Revolt, concludes Memmi, remains the only option of the oppressed.

His book thus draws the portraits of a dialectically linked duo whose fates are intertwined, both of whom are disfigured by an inherently poisoned relationship built on myths and lies, but also on the force of law and economic exploitation. Only a complete break with the colonial arrangement can rescue both the colonizer and the colonized.

Landing on bookshelves as decolonization struggles raged around the globe and just as the Franco-Algerian conflict reached its climax, Memmi’s message was radical, even if delivered in Memmi’s typically cool, analytic language. It ultimately became a landmark text in the anti-colonial canon.

Having penned his two masterpieces in the 1950s, Memmi is often only associated with the early period of anti-colonial struggle, which for him was only the beginning of a long and enduring career. He would go on to publish more than 20 other books and hundreds of articles, which deepened his early analysis of colonialism with his parallel reflections on the situation of Jews. Ultimately, he developed this line of analysis and reflection into a broader consideration of the interlinked forms of racism and oppression that culminated in his summa, Racism (1982).

Unlike postcolonial theorists who have tended to treat Zionism as allied with colonialism, Memmi made a compelling case for aligning Zionism with anti-colonial nationalism, rather than empire. This was initially undertaken in a period when Israel was broadly understood by the left as a decolonizing, socialist, humanist undertaking. Nurtured on the Jewish traditions of Tunis, Memmi came of age as a socialist Zionist in the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement, and he believed that Zionism articulates the national liberation struggle of the Jewish people. Just as he argued for other postcolonial states, he maintains that the State of Israel is necessary to liberating Jews from millennia of degradation and humiliation.

Memmi was always a steadfast secularist, skeptical about many aspects of Judaism. He understood the Bible, the Talmud, and Kabbalah as “monuments of world literature,” that contain, “an inexhaustible reservoir of themes, designs and symbols” but they become desiccated when they are treated as sacred texts. These views would emerge with clarity in his two masterworks on Jews in the 1960s, Portrait of a Jew (1962) and The Liberation of the Jew (1966).

Following the Six-Day War, Memmi continued to compose essays on the Arab-Israeli conflict, gathered in his collection, Jews and Arabs (1974). Published in the hostile year between the bitterly fought Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the U.N. declaration that Zionism is a form of racism in 1975, the book was dedicated to both his Jewish and Arab “brothers/so that we can all/be free men at last.” Memmi clearly hoped the light he cast on relations between Jews and Arabs would bring them closer, despite the growing antagonism and polarization created by the Arab-Israeli conflict. He wrote the book as a self-described “Arab Jew” and a left-wing Zionist, distilling his position on the conflict.

In his essay, “What Is an Arab Jew,” Memmi explains that most Jews in Arab lands were culturally Arabs: in their language, clothing, cooking, music, and daily habits. But a peaceful and unproblematic coexistence between Jews and Muslims is a myth, he insists—a narrative fostered mostly by Arab propagandists and European leftists. He also suggested that the myth of peaceful coexistence appealed to Israelis hopeful of a utopian coexistence in Israel and the nostalgic viewpoint of Jews from North Africa looking back on the places where they grew up.

Even Western Jewish historians who compare the experience of Jews in Russia less favorably to the experience of Jews in the Maghreb reinforce the legend, according to Memmi. The relationship between Jews and Arabs was fragile, and occasionally erupted into overt hostility or violence.

The myth of peace before the rise of Zionism has its double in the role played by “Israel” within pan-Arabism, he argues. In “The Arab Nation and the Israeli Thorn,” Memmi explains how Arab states constituted “Israel” as the evil Other in order to create Arab unity. In the face of their divergent social structures and internal challenges, “Israel” enables Arab regimes to symbolically coalesce around an enemy. It provides coherence, but at an exorbitant cost—“for this policy of waging war exhausts their economies’ possibilities in advance, [and] impedes all efforts at democratization.”

While clearly critical of Judeophobia in the Arab world, as a left-leaning Zionist he was also critical of Israeli policies. In “Justice and Nation,” he set forth his belief that Israel must adhere to a socialist Zionism he hopes will form the core of the country. “[I]f Zionism is not socialist,” he writes, “then it loses some of its meaning, for Zionism is not concerned only with the building of a nation; Zionism has aimed for the social, economic, and cultural normalization of the Jewish people.” In accord with this socialist ethos, Memmi argues for the need to address the growing inequality within the country. He also called out Golda Meir’s racist language with respect to the Mizrahim (as Jews from Asia or North Africa are called), slurring them by suggesting that they came from barbaric places where they previously “lived in caves.” Mizrahim in Israel, he objected, were slotted into menial jobs and denied leadership positions as a result of Ashkenazic hegemony.

Memmi spoke without any illusions about the fact that many in the Arab world wanted to destroy Israel. But he was also clear that Palestinian nationalism cannot be swept under the rug. He waves aside “post-Zionism” or the notion that Israelis and Palestinians can live harmoniously in a single democratic state. He believed that a two-state solution was the only long-term option.

Memmi’s last major work, the 2004 essay, Decolonization and the Decolonized, was both widely read but also drew sharp condemnation 50 years after his first major publication. He upset many with his direct and unbridled reproach of postcolonial states, especially those in the Arab world, as well as his criticisms of Muslim immigrants living in France. For some of his readers post-Sept. 11, he echoed the Islamophobic and xenophobic sentiments of the dominant culture more than he expressed compassion for the perspective of the dominated.

Memmi took little pleasure in clearly articulating the pathologies of the postcolonial Arab-Muslim world. In general, these states are not democratic. They are rife with violence. Due process and the rule of law are often only a fantasy. Exploitation by the elite is rife, torture a system of discipline, the subordination of women widespread, and intellectuals with a critical spirit are often repressed. The result is that fundamentalism is on the rise and Islamicist terrorism too often condoned or sanctioned.

The careful reader will notice that Memmi is as sensitive to the enduring forces of colonialism, and the ongoing racism faced by immigrants as ever. “Immigration is the punishment for colonial sin,” he writes. It has placed the ex-colonizers in a bind, since migration was initially sanctioned for labor. This work is still needed, given the demographic decline in Europe. But the large numbers of migrants in the last generation and their differences of culture and religion have created new problems for Europeans who often exploit and marginalize immigrants from the Arab Muslim world. The result is that they turn inwards, reinforcing their cultural difference: “This ghetto is both a rejection and a reaction to rejection,” he wrote.

Since 1989, these tensions and conflicts have often centered in France and elsewhere in Europe on a series of scandals about the wearing of the headscarf. Ever the secularist, according to Memmi, the headscarf is nothing but a form of female subjection, a submission to a backward-looking fundamentalism, an abdication of freedom, an identitarian flag. Still, he does understand it, as he does Jewish customs, as a response to daily humiliation, which he sees everywhere, since the Muslim minority is also the subordinate class. As he argued in the 1960s, immigrants are the “new slaves.” He also recognizes that the ostensibly secular order is, in fact, a reflection of a Christian culture, since holidays are all based on the Christian calendar and public monuments reflect a Christian collective memory.

Memmi focused in his later years on drawing life lessons. “One must live, act and think now, in this life, as if one were worthy of a hoped immortality. To be brief, find and communicate the truth, if possible. Beware of prejudice and utopias, of all dogmas, including those that are one’s own. Live without submission and without compromise. For me, this is the ethics of the thinker and the foundation of what I mean by philosophy.”

These were, indeed, the maxims of one of the great heretical Jewish voices of the last century, a writer whose insights we need now more than ever. If I cannot sit shiva, I certainly mourn his passing.

Jonathan Judaken is the Spence L. Wilson Chair in the Humanities at Rhodes College.