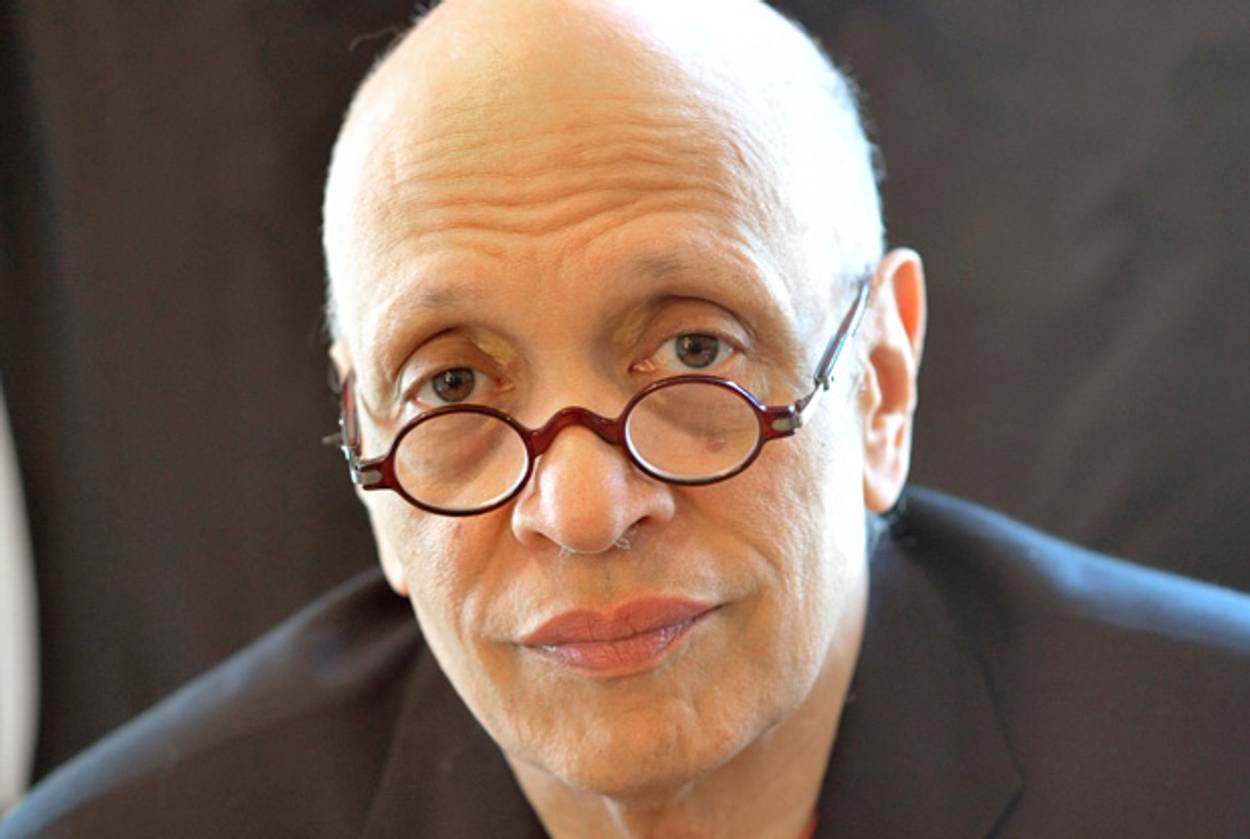

America’s Blackest Jewish Writer

Walter Mosley talks about his best-selling books, Jewish L.A., and identifying with Isaac Bashevis Singer

In April 2010, an article appeared in this magazine arguing in favor of Walter Mosley’s inclusion in the American Jewish literary canon. The son of a black father (Leroy) and Jewish mother (Ella Mosley, née Slatkin), Mosley writes novels whose fictional heroes tend to be black males. Yet Mosely self-identifies as both black and Jewish, and significant elements of his work are identifiably linked to the Jewish experience.

Last month I caught up with Mosley at the Soho House in Manhattan to discuss his new novel, Little Green (the first installment of his famed Easy Rawlins series to appear since Blonde Faith in 2007). Our conversation allowed us to explore more deeply the influence of his Jewish identity on his writing.

Asked to define how his Jewish experience shaped his consciousness, Mosley didn’t hesitate: “I remember one day I went over to my friend Steven Kahn, and Steven’s parents were German Jews,” he said. “I was talking with Steven’s father Ernest—this is maybe 1968 or ’69—and he says, ‘Walter, let’s debate the war.’ And I said, ‘Ernest, I don’t know if we disagree about the war.’ And he said, ‘It doesn’t matter. You take a side and I’ll take the other side.’ And I remember thinking, ‘This is part of my heritage; this way of arguing and thinking.’ ”

Mosley attributed his seamless identity to growing up in L.A., where, he observes,“people kind of blend together.” He recalled strong memories of both Jewish and African-American relatives: “My cousin Lilly used to teach me Yiddish curses in English. I remember one—she said: ‘You should be like a chandelier—hanging and burning.’ It was kind of wonderful. I love my cousin Lilly, so I identify with my cousin Lilly. I love my cousin Alberta on my father’s side so I identify with Alberta. And through those identifications and that language and the joy that we spent, I created a notion of myself.”

Though racial conflict in America provides the backdrop to most of Mosley’s novels, he claims to have been largely protected from racism growing up. “I had an easy time. My parents loved me very much and protected me from most bad stuff. And they were happy in their own lives,” he said, suggesting that any ambiguity he felt about his own identity was imposed upon him by others. “Jews will ask me, ‘What’s it like to be black and white?’ ” he said. “So, of course the preponderance of the details of my life is going to be in black America because I’m forced there even by my own people.”

Identity, Mosley suggested, needs to evolve in order to remain relevant. To illustrate his point, he recalled a conversation he had with a Jewish Orthodox colleague when he worked as a computer programmer; despite his strict observance of Shabbat, the colleague would use the phone on Saturdays because his father was old and sick. “ ‘If he needs to call me then I have to answer that phone,’ ” Mosley recounted the colleague saying. “ ‘That would be a crime greater than answering the phone on Shabbos.’ And you know, it’s kind of wonderful. What I feel is that we’re always broadening.”

Asked if he identifies with other writers from the Jewish canon, Mosley tends to eschew more typical narratives of American Jewish urban angst. “In my pantheon, Bernard Malamud, Isaac Bashevis Singer—there’s some unbelievable writers,” he said. For Mosley, the appeal of these writers over others is their universality and their ability to adapt and develop: “People are changing. The world is changing. One of the great things about Singer is that he kept changing. Even after he won the Nobel Prize he wrote completely different books.” Mosley is less interested in a writer like Philip Roth, whose work he feels has a “laser-like” focus on the Jewish experience.

His current projects reflect values that he ties directly to his Jewish worldview. Little Green is, at heart, about adaptability. Its fictional hero, Easy Rawlins, emerged as a detective in the Los Angeles of the late-1940s and ’50s. At the start of the new book, Easy wakes up from a coma—the result of a car accident—and walks into the flower power generation of 1967 as a middle-aged man. “In 1948,” Mosley said, “there are just places you can’t walk in the front door. They’ll say, ‘What are you doing here? If you’re a service person, go in the back door. If you’re not, go away.’ In the 1960s, he can walk in the front door but they won’t want him to do that.” Mosley added that if a writer doesn’t evolve, the work can become “like pabulum.”

He is completing a series of six novellas under the general title Crosstown to Oblivion (published in pairs in three separate volumes; two of three volumes have appeared); all of the novellas are anarchic, with a black male hero destroying a morally and spiritually corrupt world in order to bring about rebirth and renewal. Toward that end, his recent novel Parishioner is available only as an e-book; as he explains it, the Marxist in him resists becoming “a cog in a production line” and e-publishing gives the artist increased control over his labor.

Mosley enthusiastically welcomes Jewish readers who are drawn to his fiction because of a feeling of shared cultural experience or a common identity. “I know that people who aren’t insecure about their identity and who are Jewish like hearing that I’m Jewish,” he said. He also knows that his dual identity gives Jewish readers “an entrée” into the African-American experience. And, because his Jewish learning and political orientation run deep in his life and work at an unconscious level, he welcomes the notion that his Jewish readers “might see things in my work that I don’t see.”

And the arrow points in the other direction, too, as Mosley celebrates moments of acceptance in his life and in his experience as a Jew. “A long time ago I was talking to a rabbi, a young rabbi who was a student at City College,” he recalled. “And I said, ‘I’m Jewish too you know.’ And he kept talking. And at one point I said, ‘I said I was Jewish and you didn’t bat an eye or ask a question.’ And he looked at me and he goes, ‘Who would lie about that?’ Now, I got that.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Harold Heft, Director of Research and Innovation at North York General Hospital, has taught literature and film at the University of Western Ontario and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Harold Heft, Director of Research and Innovation at North York General Hospital, has taught literature and film at the University of Western Ontario and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.