Forgotten Stars of the Old New Yorker: Arturo Vivante

A tribute to the great Italian-Jewish memory artist, and enemy of Fascism, who died six years ago this week

On a recent visit with Lydia Vivante, the writer Arturo Vivante’s daughter, we sat in his old-fashioned kitchen in Wellfleet, Mass., drinking iced tea and eating cut sandwiches, talking about her father, who died six years ago this week. “Yes,” Lydia said, speaking of her father’s internment as an enemy alien and as if to explain the airy surroundings, “the enclosed camp in Canada haunted him his whole life.” He seemed in many ways still to inhabit the sloping rooms. The house was filled with objects shaped by the human touch: paintings by Arturo’s mother with serpentine-shaped trees and boldly colored wildflowers; books with handmade covers; old fashioned carpentry—door moldings and a cabinet Arturo built himself. As I looked around, I thought, intimacy is the enemy of Fascism—exactly the right weapon for the man who had been so unfairly imprisoned as a child in 1940.

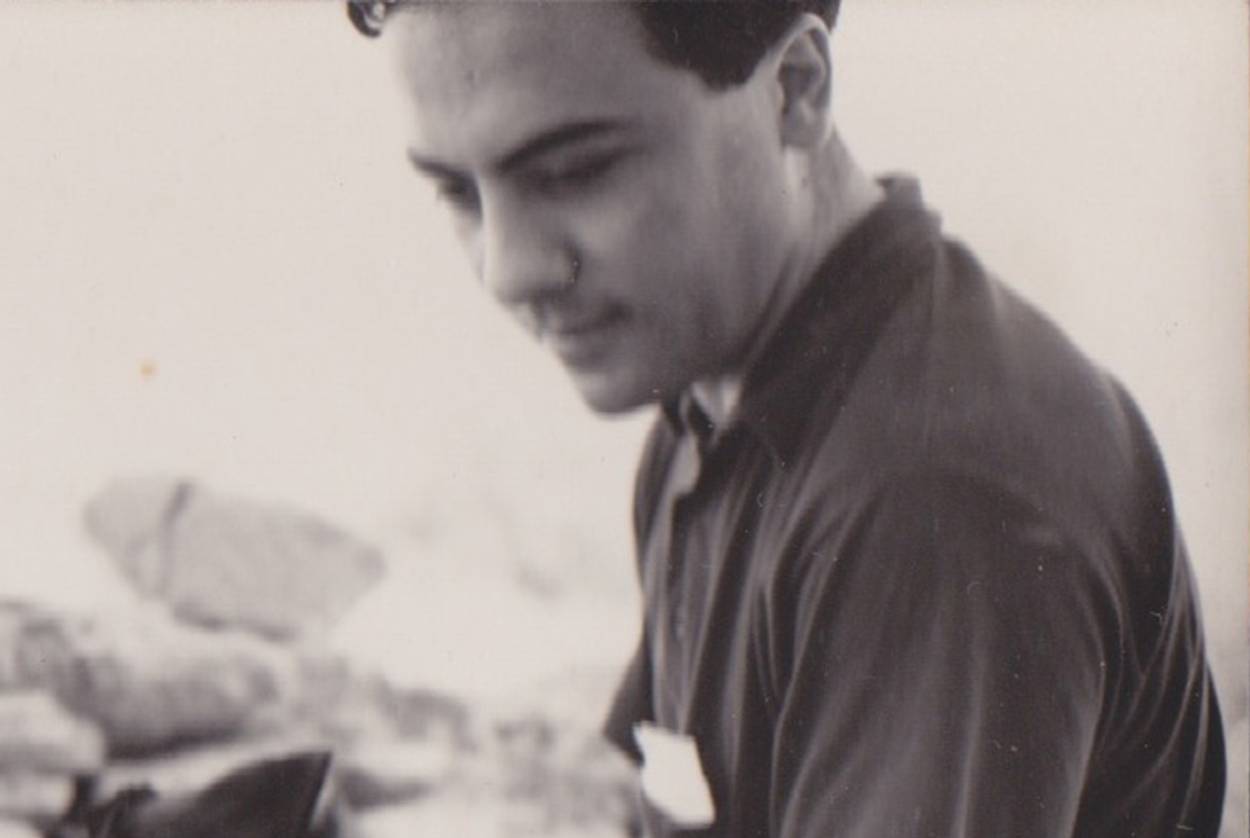

Arturo Vivante was dashingly, poetically handsome as a young man with wide, strong shoulders and dark, penetrating eyes. In the house there are many photographs of him, framed prints and snapshots in boxes, envelopes, and drawers. When I knew him as his friend and sometime editor, he was already white-haired, paunchy, even neglected-looking. He usually wore a work shirt loosely tucked under his belt, the sleeves rolled up. He didn’t care about clothes. There was a joke among his relatives that the Vivantes were a little “recessive,” by which they meant unaggressive and even other-worldly, a whole household of Ferdinand the Bulls, but the house is stamped by his personality—unstudied, passionate, gentle, and witty in a deep and slightly gloomy way. Between 1958, when he was still working as a doctor and living in Italy, and 1983, when he was teaching at Bennington College, The New Yorker published more than 70 of his memoiristic stories. For the literary magazine Formations, I edited several of his later pieces, which ranged from a vignette about his mother as a village art teacher just after the war to a mocking self-portrait of himself 30 years later, ever a connoisseur of feminine beauty: “Why should one avoid beauty at whatever age, of whatever age, anywhere, anytime, even at a funeral service?”

Although it appears at the margins of many of his family stories set during his childhood or the postwar period when the family experienced a grim reverse of fortune, Vivante had little interest in his Jewish identity. “He never learned anything about it,” his daughter explained, matter-of-factly. Nonetheless, his early years—with an oversized, eccentric, and demanding Jewish father—and then the war years, haunted him his whole life. This can be seen in just about everything he wrote and became very much a part of his unhindered spirit. Like the work of writer and artist Bruno Schulz, Vivante’s stories are filled with profound and unflattering self-portraits—the abject lover throwing himself at a woman’s feet, for instance—and there is often a degree of self-loathing or at least self-deprecation in those sketches when the woman draws away from the lover’s hold and goes to a younger man. I have a little stack of letters and cards that he wrote to me in his small, tumbling handwriting during those years—courteous notes about copyediting or honoraria, New Year’s greetings, thoughts about artwork, condolences when a family member died—but the first was a postcard of Watteau’s Old Savoyard and the last was a detail of Botticelli’s Primavera.

***

Vivante was born in Rome in 1923, the second of four children in a family with deep roots in literature, philosophy, and the arts. His mother’s family was not Jewish but freethinking, humanistic, and anti-dogmatic. His mother, Elena Vivante, was an artist who painted landscapes and gardens, fiery poppies and vibrant yellow irises, recording the natural beauty of the family’s estate, Villa Solaia, near Siena. (In the 1950s the family took paying guests at the house, which was visited by the poet and lichen specialist Camillo Sbarbaro, Eugenio Montale, Shirley Hazzard, and many others.) Elena Vivante’s father, Adolfo de Bosis, founder of the journal Il Convito, was a poet who translated Shelley into Italian. He was friends with the American-Jewish sculptor Moses Ezekiel, who made a silver plaquette of him. Elena’s brother, the translator, poet, and teacher (he taught Italian at Harvard), Lauro de Bosis, won a medal in the 1928 Olympic Art Competitions for his verse play Icarus and became an ardent anti-Fascist. He died tragically in 1931 when the airplane he flew, distributing leaflets over Rome, was lost at sea. Lauro, who believed in “the religion of Liberty,” left behind an essay, “The Story of My Death,” which was translated into English by his companion, the actress Ruth Draper. It was published in many newspapers and journals in Europe and the United States and republished by Oxford as a pamphlet in 1933.

The rise of Fascism was the central and inextricable fact of Arturo Vivante’s childhood. He writes about this in one of his most moving stories, “The Sound of Cicadas”: “In the early thirties, when my brothers and I were children, if we saw an airplane flying over our house in the country near Siena we would wave, then run into the house to tell my mother about it. ‘It was flying really low,’ we would say, hoping to stir her. ‘Perhaps it was our uncle.’ We would watch her. But her face wouldn’t brighten.” The Fascists had taken away his mother’s happiness, but he transformed his anger into a particular kind of resistance: the habit of informality, modesty, and self-effacement. Anti-totalitarianism can be seen in his choice of medicine as a first profession, which, he wrote as an aside in one of his stories, “seemed more humane than the humanities.” Arturo accepted the human body and its indignities. He could look straight at an old woman’s thighs, “thin as forearms,” or a baby’s diaper, without flinching.

Arturo’s father, Leone Vivante, came from an assimilated Jewish family. He was an idealist, a philosopher who never looked for a university position but wrote his books and articles at the estate in Tuscany, which his father purchased for him. This was “in the hope that his son could become self-supporting.” In Arturo’s story “Of Love and Friendship,” he memorialized his parent’s Bergmanesque marriage and his mother’s friendship (and perhaps infidelity) with Sbarbaro. Leone is described as self-absorbed, “irritable, willful, and so determined.” A lousy businessman, he planted a beloved peach orchard that withered during spring frosts. He loved American movies and the company of women. T.S. Eliot wrote the introduction to his volume on the English poets. Leone’s maternal grandfather, Graziadio Isaia Ascoli, had been an eminent professor of linguistics at the University of Milan and a leader of the Jewish community. An autodidact whose father built factories that produced thread and paper, he wasn’t allowed to go to school as a boy because he was Jewish. (He joked that he had both the virtues and the vices of never having attended school.) Ascoli was a scholar of many languages, Italian dialects, and Romani and founded the linguistics journal Archivio glottologico italiano, which continues to be published today. Leone’s father, Cesare Vivante, was a famous professor of law. Arturo wrote a poignant portrait of his grandfather in the short story “Adria”:

an energetic little man with a goatee, who was reputed never to have lost a case. The walls of his office, which was in the house, were lined with textbooks, many of them written by him, and bound copies of the journal of which he was the editor-in-chief. He was an authority on commercial law, which he taught at the university. … He had become a full professor at twenty-five, sent his brothers through college, written some laws, and built the house in Rome. … He was headstrong cocky, impatient, vain, opinionated, brilliant to the point of sharpness, and at the same time cheerful, gallant, generous, literate, and refined.

For most of Vivante’s childhood Jewishness was noted but not stigmatized, even looked upon agreeably. As he wrote there, “at least, in Italy Jewish families were known for the high degree of affection and respect existing between them and whoever worked for them in the house.” All this changed, of course, by 1938 when Hitler visited Rome and the anti-Semitic campaign began. The family decided to go England as refugees. Lucy Vivante, Arturo’s older daughter, said to me, “Knowing how other-worldly they were—you could say poetry was their religion, they all could quote long passages from the Romantic poets—it’s amazing they even recognized the need to leave.” But the departure was well-orchestrated. Cesare Vivante, then in his eighties and expelled from the Accademia dei Lincei for being Jewish, moved from Rome to the family’s estate in Siena. The rest of the family left in several stages so as not to draw attention. Since there was danger they could be shot on sight if the Fascists suspected they were not coming back, the parents made several trips, taking their sons at different times. Their daughter came last with a non-Jewish aunt. Each time, they traveled by train to Paris, carrying only an overnight bag since they declared at the border they were just going for a visit. In France they caught the ferry to England and then went on to Wales, where they had friends. In the bag they carried rare books obtained from their friend, the publisher and rare-book dealer Leo Olschki, who was also Jewish. He had given them names of buyers in England who would provide them with money they would need for expenses. In England, the family was separated; the oldest brother went to Oxford, and the other children went to different boarding schools. The parents lived in Surrey, then Oxford and London.

After Mussolini declared war, all Italians living in England were classified as “enemy aliens.” Arturo, who had recently turned 17, was taken from the King’s School in North Wales, where he had already experienced the petty tyranny of British boarding-school culture. He was put alone in a country jail before being sent to Liverpool. Then, with 3,000 German war prisoners, Italian sailors, and other refugees, he was shipped to an internment camp on St. Helen’s Island in Canada, where he remained for nearly a year behind barbed wire and separated from his family. He was the youngest prisoner. The trauma and unfairness were hard to bear but reinforced his loathing of constraints. In a twist of fate, Vivante’s grandfather lived unharmed on the family estate while it was occupied by German soldiers. When Cesare became ill, a German doctor took care of him. The doctor attended his funeral and, when he died in 1944, the soldiers carried his bier.

Arturo Vivante’s stories span out like spokes around this history and its lessons. His sensibility was always artless artistry. Characters’ names—first names only—are introduced through conversation the way we learn them in reality. His stories are more like sketches or studies, deliberately limited in subject, scale, and even language, staged within the narrow and often humble settings of a dinner table, a bar, or on a train. Like other transplanted writers—he wrote in English—he savored the inventiveness of the colloquial, choosing “bright” rather than “smart,” for example, when describing intelligence. He worked to sound natural and matter-of-fact, testing his sentences out loud by saying them “badly” to catch the awkward, real rhythms of conversations. Profanity didn’t interest him; it must have reminded him of the marches and shouting, the “dark times” of the 1930s and ’40s.

The last time I saw Vivante we were at the house in Wellfleet. It was summer and we sat outside at a long, cloth-covered table in the narrow, shaded lot behind a village tavern. It appeared the whole neighborhood was invited. A little girl rode around the grass on a bicycle. Arturo strolled from chair to chair and, with a gesture of intimacy, not familiarity, gently reached over shoulders to add formaggio to the plates.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.