‘Brighton Beach at War’

Drinking wine with Russophone New York’s funniest shtetl poet

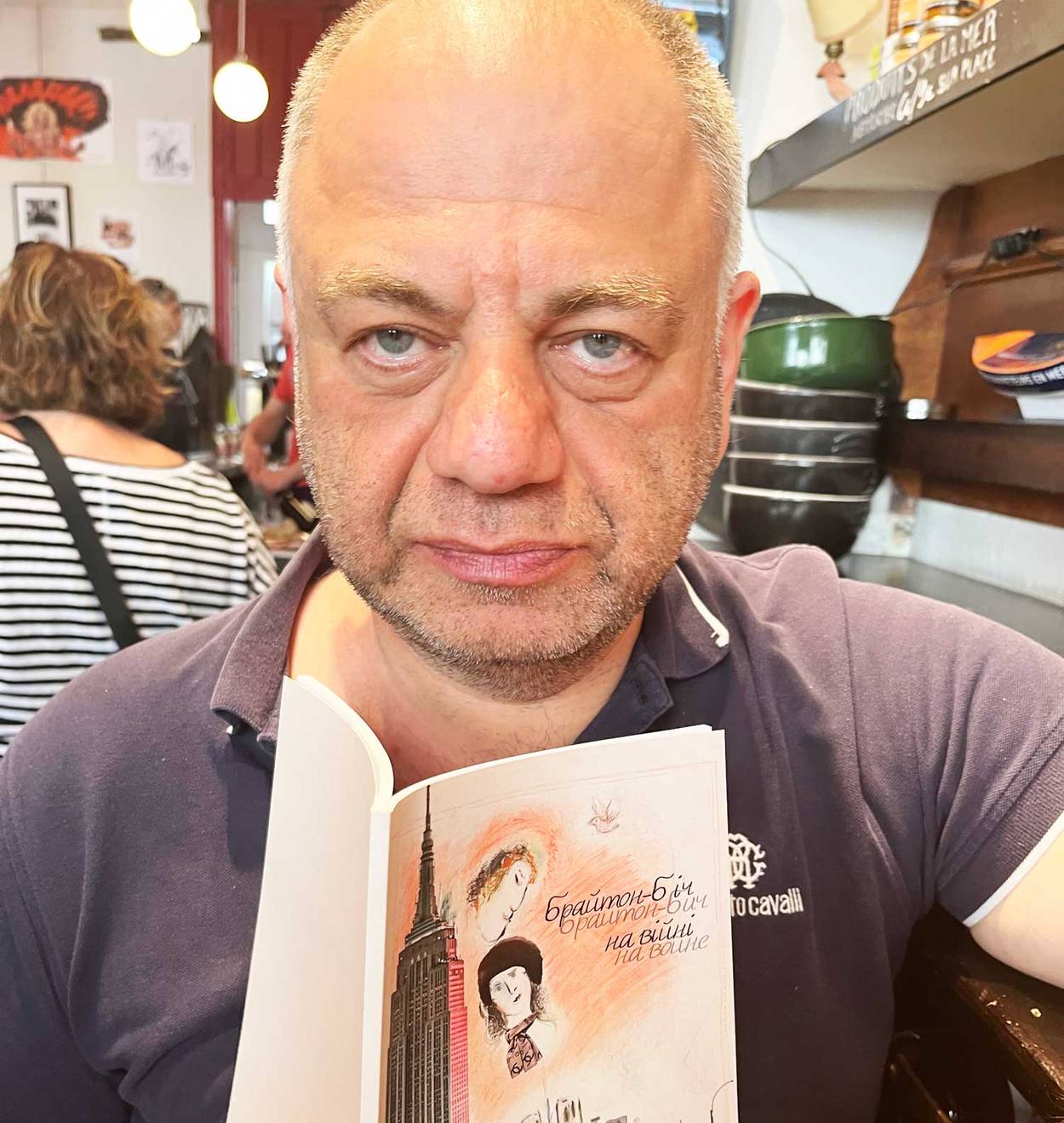

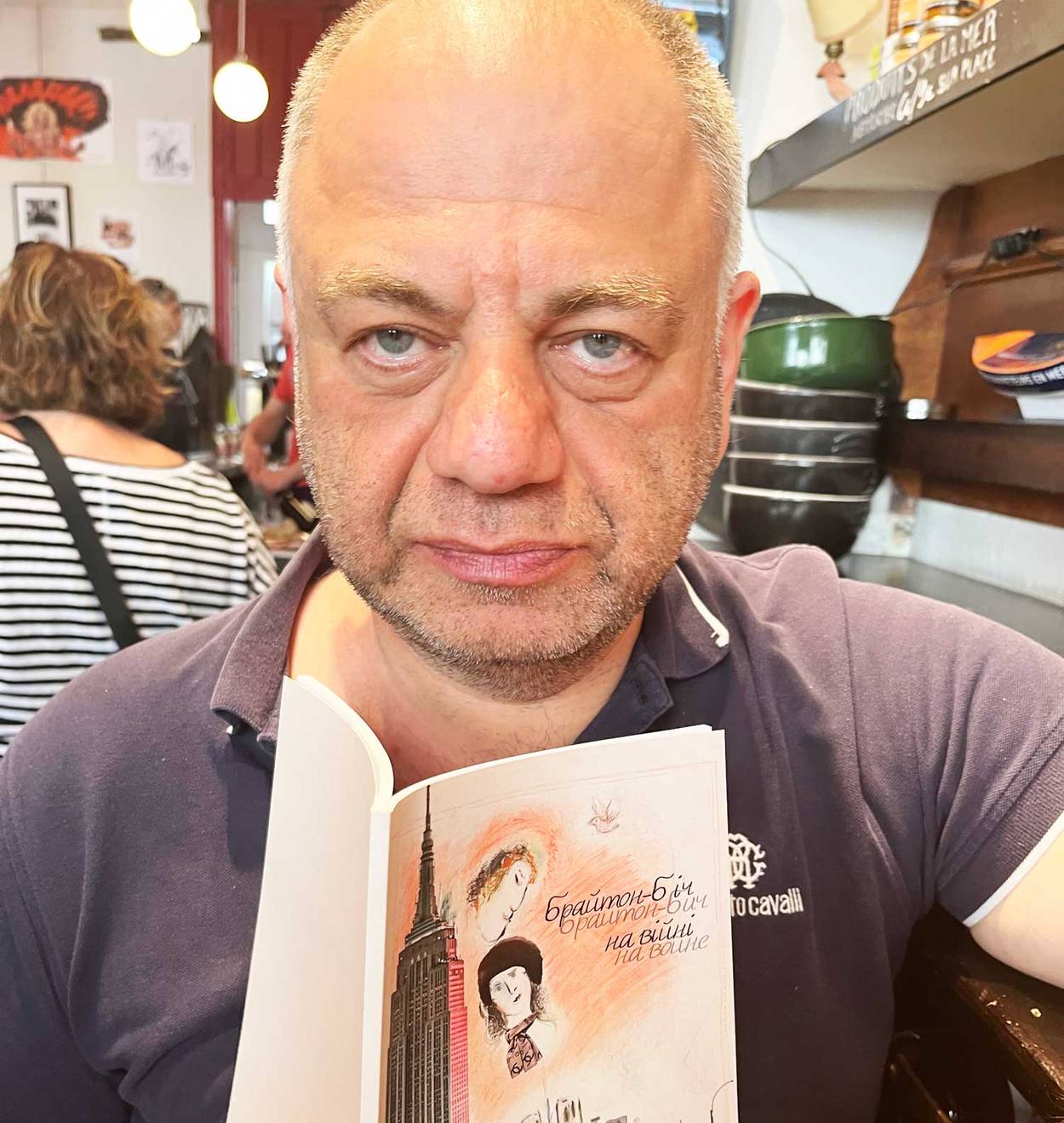

On the rare weekends when I am at home in Paris, my weekend ritual involves a trip to the Marché d’Aligre. The produce market, located between the Gare de Lyon and the Bastille Opera house, is where Parisians go to haggle for moderately priced fresh fruit with Arab gentlemen before repairing to the adjoining flea market to acquire old stamps and antique books. The market is also home to the Baron Rouge, one of the grandest and most old-fashioned bars in Paris and a beacon for scruffy bon vivants, bohemians, and buccaneers of all sort. The peeling paint on the bar’s walls is blood red, and the perennially overcrowded establishment is lined with wine barrels. A glass of the most delectable Sancerre or Chablis can be had for 3 euros or so. It seemed like the perfect place to take Alexander Galper, the author of the funniest, tragicomic response to the Russian war against Ukraine, Brighton Beach at War.

The Kyiv-born American poet had called me that morning to let me know he was passing through Paris in the final days of his monthlong European reading tour. He had just spent a week in Ukraine, and I was curious to know how his new writings on the war had been received in Kyiv, which, for understandable reasons, has less and less patience for Russian-language writing. I was also keen to know what effect the war had wrought on opinions back home in Russophone New York City—the world I grew up in, but which I left in my mid-20s and have only intermittently stayed in touch with. Galper, it should be noted, is one of the funniest men I have ever met. Who can resist a good laugh in times of war? I duly invited the poet to come out to the Baron Rouge.

A former computer programmer who is now a social worker for drug addicts and criminals in New York City, Galper has kept up with poetic vocations and puts out slim volumes of light verse every couple of years. These volumes include wild stories about his drug addict patients, such as the one about a stockbroker who went crazy and began to meow like a cat. Galper is not a tall man, yet he possess an exuberant and charming personality that dominates the room. His sense of humor is of the old-fashioned, Russian Ukrainian Jewish type, which, on a man with less wisdom and aplomb, would make him come across like a provincial shtetl Jew. Heavyset, bald, and with a heavy beard over his jowly face, the 52-year-old Galper resembles an Eastern European heavy right out of central casting—which is why he often has the occasion to play one as an extra in gritty HBO productions.

Having arrived in 1980s America at the age of 18, Galper quickly enrolled at Brooklyn College to take classes with Allen Ginsberg in its English department. The Beat poet would be a great early influence. Galper translated him into Russian, and the two discussed the sexual proclivities of the Russian poet Sergei Yesenin, who was bisexual. “He never came onto me because I was too chubby and looked like a Russian mobster from the Sopranos,” Galper relates with a laugh in response to my asking the obvious question. “I had heard so many stories from my friends and fellow students about him picking up young men from his classes, and so I was really very much expecting the same treatment. But I was too chubby and so he never made a pass at me. YES. I was rejected by Ginsberg. Which left me so disappointed, you know, not to be sexually harassed by Ginsberg!”

Like your prototypical mischievous uncle, Galper communicates almost exclusively in bawdy Jewish anecdotes and parables. “So Abraham walks in on Sarah and her lover. Enraged, he takes out his pistol and shoots dead the man that he has caught in bed with his wife. Sarah responds to the shooting calmly: ‘Abrasha, if you keep behaving like that you won’t have any friends left by the end of the month.’” This parable relates to the core aesthetic of Galper’s art, which melds a simple shtetl playfulness with the knowing cosmopolitanism of a modern New Yorker.

Galper’s 10th volume of poetry, Brighton Beach at War, is a serious response to the war written entirely in a humorous register. The war had thrown the world’s Russian-speaking diaspora into existential questioning of its core presuppositions and values. The literary responses produced by emigre Russophone writers have consisted mostly of endless tirades, schismatic arguments, and mutual denunciations over Facebook. That sort of self-righteous nastiness is a core part of our culture and should not surprise anyone. Yet the question of the morally and aesthetically proper response to the war among the emigres remains highly relevant.

It should be said that while Galper’s poetry is born of the same impulse, it is far less formally interesting than his prose pieces. Some of his light blank verse flirts with being doggerel, but is saved by the fact that the staccato lines are mostly hooks for telling yet more jokes. Some of the poems, such as “Mariupol,” are deeply moving ruminations on Galper’s response to the war. They are also funny. What is the responsibility of the Russian-speaking Ukrainian Jewish poet as he observes from Brooklyn the army of Pushkin’s culture pounding his ancestral land with rockets? What did you do, God asks the poet, when the Russian army leveled a city to earth?

The answer that the poem proffers up is simple, honest, absurd, and also deeply unsatisfying:

I could not catch those bombs with my hands,

I did what I could.

I wrote posts on Facebook

About the tragedy of Mariupol, in Russian.

The words “in Russian” do not look particularly idiomatic tacked on to the end of the poem in the English translation. In the original, the fact that they are the last clause of the poem is very much the rueful point.

Galper’s shorter prose pieces, on the other hand, are based on authentic distillations of the Russophone Jewish life of Soviet emigre New Yorkers, as well as dialogues taken directly from Galper’s own life. “Nu, why did Putin bomb the Jewish cemetery in Bilo Tzerkva?” A character asks. “He blew up the gravestone of my sister Chaya. Of course everyone hated her because she slept with other peoples’ husbands. But still—can’t he leave her alone after she is gone?”

Many of the absurd or surreal tales in the book are told through the recurring character of Aunt Ida, a meddlesome, ornery, and archetypical yenta. Aunt Ida frets about her mother not wanting to move to Israel amid the bombing—the president of Israel calls her himself in the story. Aunt Ida worries about her translator brother being stationed in Warsaw and not having a chance to be at the front; she also worries that her cowardly nephew will return to Kyiv from New York City. In one of these pieces, the elderly aunt forgets her heroic World War II service and has to be reminded that she was part of the victory against the fascists bombing Kyiv. She is incredulous in a totally understandable way—did we really defeat the fascists if Kyiv is still being bombed?

I first met Galper in my misspent early 20s, while I was hanging around the Russophone emigre poet crowd in New York City. That is when I studied comparative literature and Russian at Hunter College under the tutelage of the Russian American poet Matvei Yankelevich instead of picking up skills that would make me useful to banks. Galper and I had first been introduced by the writer Richard Kostelanetz—the doyen and encyclopedia compiler of the American avant-garde. Now in his early 80s, Kostelanetz has become a reactionary, anti-establishment figure who spent many of the first months of the Russian war against Ukraine sending me dozens of increasingly unhinged and antagonistic emails referring to President Zelensky as a puppet and a schnorer. I eventually lost my temper and fell out with him, after knowing him for almost 20 years, over his insidious politics. Yet Galper saw no reason to be surprised by any of it, or for me to take the matter personally. “His current political drift was just logical,” Galper told me. “Kostelanetz is just that kind of leftist who does not care about anything except being against the establishment.”

Over our second bottle of white wine and fish terrine, Galper explained to me that the literati in Kyiv on his reading tour had been understandably skeptical of him as an American poet who was still writing in Russian. One of his Ukrainian publishers even dropped the Russian text from a new bilingual edition of his new volume, which did not bother Galper as much as it delighted him that he could not read his newly published book (when he was a kid growing up in Kyiv, most schools still did not teach Ukrainian). Another of his editorial contacts in one of Kyiv’s oldest Russian-language presses, the esteemed communist-era Raduga (“rainbow”), could no longer receive state support or survive as a Russian-language press in Ukraine. Galper was equally delighted by their new business model: Since it was already called Rainbow, it would rebrand itself as a gay-friendly press and live off of European Union grants. Still, as a poet from Brooklyn who has continued to write in Russian, it was hard for Galper to get anyone to agree to organize a Kyiv reading for him.

An editor from Raduga had the great idea of suggesting that Galper organize his reading in the old Sholem Aleichem Museum in the Kyiv city center next to the old Bessarabyan Market. No one could or would possibly care if an American Jew wanted to read his funny Jewishly themed short stories in the Sholem Aleichem Museum! “I could even read my poetry in Chinese if I wanted to!” the poet exclaimed exuberantly. Yet when he arrived, the door guard demanded that Galper purchase an entrance ticket for 50 hrivna ($1.35 as of press time). “But I am the reader!” he tried to explain, before capitulating. “The door guards had won the argument with the strong implication that I was an antisemite for not wanting to help fund the museum. What—you don’t care about Sholem?”

The Ukrainian skies still being closed to civilian planes, Galper had to take the 16-hour-long train from Ukraine to the European Union border on the way home. Arriving at his bed in the sleeper car, the poet soon realized that the grizzled elderly man who was his seatmate had been his schoolboy shop teacher more than three decades ago. His former teacher promptly produced a bottle of homemade moonshine that the two men would spend the next hours consuming. At 3 in the morning the drunken shop teacher accused his former student of having stolen a power drill from the school in the early 1980s. “I had to spend a very long time calming him down and convincing the inebriated gentleman that I had not in fact stolen the power drill,” Galper told me over our third bottle of Chardonnay. “My alibi was that I was 10 years old at the time—and thus the charges did not stick!”

Galper is a man of simple tastes, but he does drop sly hints of his admirable Old World literary ambitions. He sees this moment as his great opportunity to become the biggest Russophone writer in the entire world: “See—all of the Russian writers living in Russia, no matter how gifted they are, are still Russian citizens. They are out of the competition!” he tells me with infectious glee. “The Ukrainian magazine sponsoring my talk here in Paris—they do not even publish Russian writers. Not at all. No matter what their convictions, a Russian citizen is a Russian for them. So I have the perfect combination of being Ukrainian born, Jewish, and living in America. The perfect combination to succeed in Russian literature today is not to be a Russian. It is to be a Ukrainian Jew with an American passport!”

In my early 20s I had always judged Galper to be a bit too much of a shtetl-Jewish-type writer to be interesting as a stylist or thinker. Perhaps I am becoming a sentimental tribalist in my late 30s, yet 15 years after first meeting Galper and reading his work, I admit that my youthful judgment of his work was very much off. Galper is, after all, a well-traveled New Yorker, and the post-Soviet rabbinical Jewish funnyman shtick is much more sophisticated and self-reflective than it might seem at first glance. The war has also brought his particular sensibility into the present. And unlike so many other diaspora Russian responses to the war, Galper’s is not self-righteous, cloying, preening, or insufferable. His hilarious, politically astute, and very warm vision is very much of the moment and would likely have a great reception from Anglophone readers. I dearly hope that an American publisher reading this will commission a translation of Aunt Ida complaining about the teeth of Russian POWs being interrogated by Ukrainians on TV. “Even the officers. Where are all the dentists in Russa? Has Putin killed off all the Russian dentists? It’s horrible!”

Vladislav Davidzon is Tablet’s European culture correspondent and a Ukrainian-American writer, translator, and critic. He is the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.