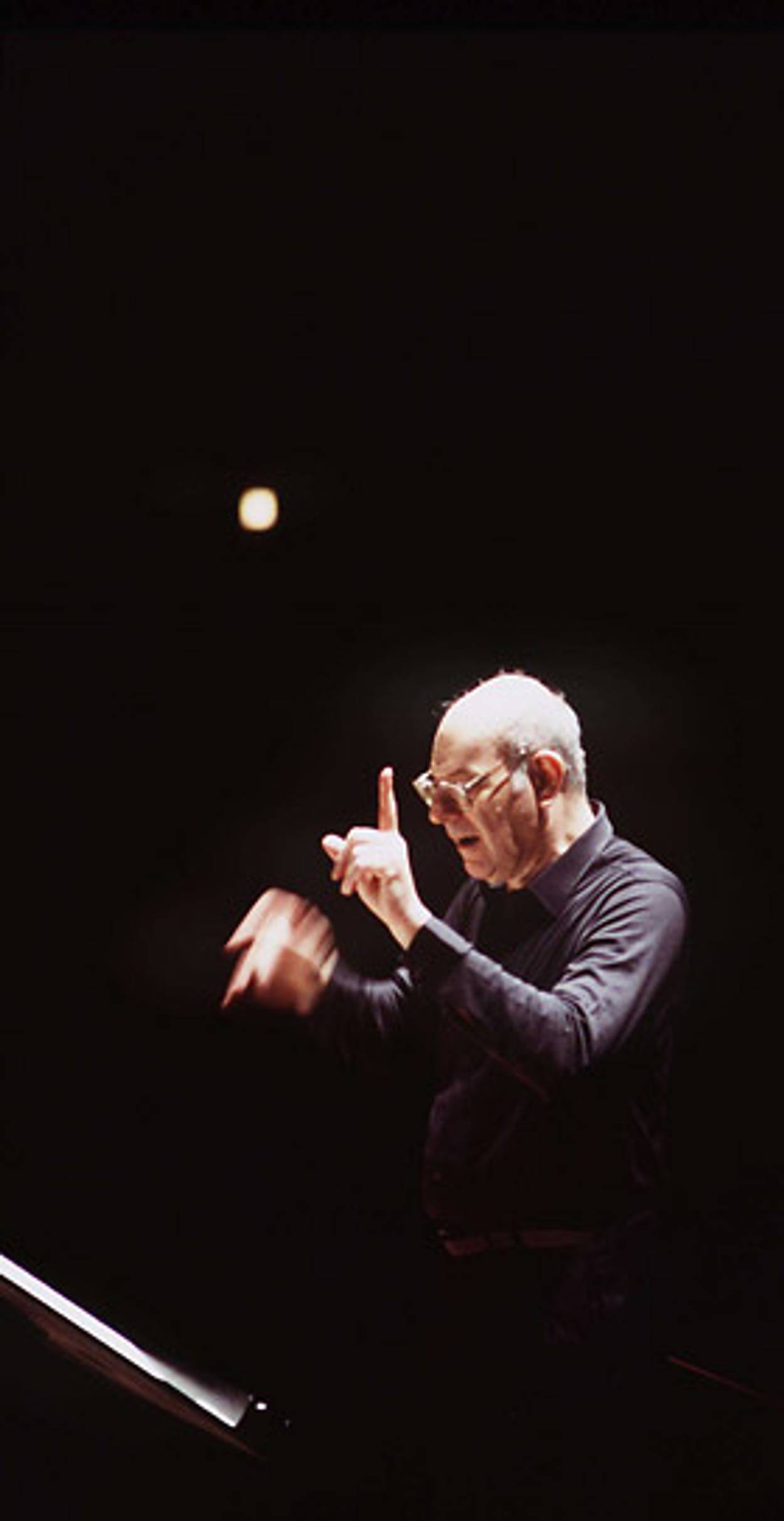

Bring the Noise

The brilliantly aggravating music and art of Mauricio Kagel

Despite his relative obscurity in the United States, Mauricio Kagel, who died in Germany last week at the age of seventy-six, was one of the twentieth century’s great conceptual artists. A composer whose assaultive music was categorized as “classical” because record stores didn’t know where else to put it, Kagel was an intellectual prankster and social provocateur on the grand, protean level of Marcel Duchamp—or Lenny Bruce. His specialty was a heady, unforgiving onslaught on audience expectations, the sort of theatrical meta-gesture that, for example, requires the conductor of an orchestral piece to feign a realistic fatal heart attack on stage.

He’s best known in the United States for his eight-year run of ear-destroying LPs on Deutsche Grammophon, back when the General Motors of classical music had an interest in the avant-garde (an association that ended, for Kagel and for the avant-garde in general, in about 1973). These were some of the noisiest, funniest, most parent-alienating albums ever released on a major label. They range from Ludwig Van, a sort-of-soundtrack album (for a 1970 film directed by Kagel) that performs upsettingly radical surgery on the music of Germany’s favorite son, to “Acustica,” an elaborately constructed ninety-minute piece for five musicians and pre-recorded tape playback that Kagel scored for an outrageous ensemble including “nail violin,” half a dozen wooden noisemakers, two Australian bull-roarers, an air compressor hooked up to a system of hoses, a demonically modified turntable, and amplified human belching, as well as—to quote the liner notes for the recent Harmonia Mundi re-recording—

handle-board, thumb piano, bell-board, humming-bird, hand cymbals, toy trombone, violin, cheek-drum, sandpaper, thunder sheet, miniature radio-door and radio-window, bellows, bell stick, box of nails, pail of water, two-voice trumpet with loudspeaker mute, panpipe, conveyor belt with glockenspiel keys and impact box, walkie-talkie, and toy animals.

Kagel was just as instinctively cheeky in his work in other media. In his short films (and one feature) for German television, he demonstrated a surrealist sense of dramatic illogic and a master’s eye for visual form, coupling his propriety-shredding music with equally propriety-shredding images: a helmeted Nazi soldier chewing with his mouth open while gazing happily into the camera, for example, or a parade of grotesque, unidentifiable body parts that wouldn’t seem out of place in a David Lynch picture (both in the opening moments of Hallelujah, 1969). He made state-sponsored radio drama out of Fascist jabberwocky (in “The Tribune,” 1979) and from the detritus of advertising culture (in “Guten Morgen!,” 1971); and when it came time to attempt an opera, Kagel created what is possibly the most thoroughly “broken” operatic spectacle ever devised—the notorious “Staatstheater,” in 1970, an epic piece of gorgeous nonsense that apparently sent Kagel’s lifelong friend György Ligeti into spasms of jealousy. (“Le Grand Macabre” was Ligeti’s response.)

Kagel was born in Buenos Aires in 1931 to parents who were self-professed anarchists, Russian Jews who fled the bloody, ideal-shattering aftermath of the October Revolution. They instilled in him the paradoxical ability to believe in humankind’s potential for good while simultaneously managing not to expect too much from it. “The most important values of Jewishness,” Kagel told the New York musician Anthony Coleman in an interview published in BOMB in 2004, are “self-irony and never-ending reflection and commentary, tolerance and paradox, humor, mysticism and mystery”—an apt description of the determining qualities of Kagel’s art. These same values were reinforced by the literary-artistic culture he grew up in, particularly by Jorge Luis Borges, with whom Kagel studied English literature at the University of Buenos Aires and who later employed Kagel as the photography and film editor for his literary journal nueva visión. As the UK-based music scholar Bjorn Heile points out in his 2006 book The Music of Mauricio Kagel (the first book about him in English), Borges’ influence on Kagel’s art is everywhere; you don’t have to go any further than Kagel’s dazzling short film Duo to see evidence of a distinctly Borgesian fascination with games and simulacra (and an abiding love of literature—Kagel was a voracious reader).

After an equally formative period spent stage-managing and coaching performers at the world-famous opera house Teatro Colón—and, notably, after his sister was briefly detained by the police during a demonstration against the post-Peron military regime—Kagel left Argentina in 1957 on a German exchange scholarship and wound up in Cologne, where he lived for the rest of his life. Drawn to Germany by the chance to work in an electronic music studio, Kagel quickly found his calling in the exploration of pure sound—an artistic journey that naturally led him into uncharted realms of composition. At the end of the 1950s, cutting-edge orchestral music was dominated by what one might call “the Darmstadt aesthetic,” after the yearly German new-music festival that brought Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Boulez their fame. The music coming out of Darmstadt at that time was predominantly serialist—composed by following logical and mathematical criteria rather than self-expression or under-theorized aesthetic preferences. Kagel’s early music, with its absurdist theatricality and South American chutzpah, splattered across the brittle pieties of the Darmstadt scene like a squirt of ketchup on a tuxedo. Noisy, comical pieces like “Anagrama” and “Transición II”—which were cerebral and funny, theoretical and expressive—had a direct and lasting impact not only on Stockhausen, who immediately incorporated several of Kagel’s unorthodox techniques (although without Kagel’s comic timing or anarchic instincts), but also on young turks like Ligeti and the great Italian composer-conductor Bruno Maderna. Through the 1960s and into the 1970s, and even more than John Cage, Kagel offered a profound counterexample to dominant musical practices; he brought the sensibility of the 1960s into classical music before the 1960s even started.

Kagel’s particular kind of humor—coldly cerebral and pointedly aggravating, like a combination of Samuel Beckett and Jerry Lewis—was (and surely remains) the major reason why Kagel’s music is absent from the seasonal programming of the major American orchestras. Of course Kagel’s music was just one of the elements in play in the musical avant-garde of the 1960s, which in places like San Francisco was evolving into something altogether different from the Darmstadt model. Those years saw an explosion of theatrically oriented avant-garde performance units in a variety of musical genres, both in the United States and Europe. If Kagel had a core demographic in America, it was the wacked-out kids who tore their minds open on Zappa and Sun Ra—the ones who heard beauty in dissonance and saw fascism in mainstream music of all kinds. In the United States, Kagel left his mark most deeply on the emerging downtown noise movement in New York City, who pounced on the Deutsche Grammophon albums like Der Schall and Exotica—Kagel’s most deliciously irritating music—and found in them a path out of the swamp of bourgeois leisure listening.

Those who felt Kagel’s impact most deeply were young musicians like Coleman, who attended Kagel’s summer seminar in France in 1981, and John Zorn, who as a high-school student discovered his avocation after listening to Kagel’s sensationally weird composition for organ and choir, “Improvisation Ajoutée.” By the time Coleman met him, Kagel no longer had a record contract in the United States, and the masterpieces of the early 1970s were out of print. “The records never sold particularly well,” Coleman told me recently, “so they were in cutout bins, and there were a lot of freaks all over the country who were looking for weird music and who found themselves blown away by it.” Coleman—who participated in a performance of Der Schall in New York this year—knew Kagel only by reputation when he first heard his music in the late 1970s (in Zorn’s East Village apartment); he went to Europe to study with Kagel partially because no one knew what had happened to him since his heyday.

Today, only a smattering of Kagel’s music is available to the average American consumer. But the real injustice is how little of his film work has managed to make it to these shores. His sharp eye for a well-balanced frame and his spookily adroit cinematic technique were already on display in his earliest films for German TV (the first, Antithesis, was shot in 1965). He managed to create, on a precarious budget, the kind of purely musical cinema that Powell and Pressburger labored so mightily, and expensively, to achieve; if he hadn’t been an essentially non-narrative filmmaker, he may very well have been listed among the leading lights of the New German Cinema like Fassbinder and Werner Schroeter. The short films—like Duo, a 1968 slapstick freakout that concludes with a Brakhage-like explosion of scratched celluloid and shards of black leader—are relentlessly of the moment; they are at once completely abstract and unmistakably reflective of contemporary German society.

In other short films, Kagel staged a bizarre piano dialogue with F.W. Murnau’s silent horror film Nosferatu (in MM51, 1983), traced the connections between choral performance and scatology (in Hallelujah, 1969), and submerged European art music into its latent fascination with racial otherness (as in the 1981 Blue’s Blue, about a fictive Delta blues musician). But his masterstroke was surely his 1970 quasi-narrative feature film Ludwig Van (subtitled “A Report by Mauricio Kagel”), a titanic assault on the “official culture” of classical music in the West—and Germany in particular—that must have been quite a slap in the face to those who viewed its first broadcast. Commissioned by Westdeutscher Rundfunk for the 200th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth—as part of the same state-sponsored initiative that produced Stockhausen’s notorious “Beethausen Opus 1970 von Stockhoven”—Ludwig Van opens with a long, wordless sequence taken from Beethoven’s own P.O.V. as he wanders through post-industrial Bonn (complete with puzzled reactions from unrehearsed pedestrians) and closes with a montage of orchestra musicians’ feet intercut with the bowel movements of elephants. Kagel’s stance towards “official culture” was never so boldly stated—and seldom so acidic—as in his exploration, here, of the commodification of Beethoven’s legacy. Halfway through, the film is interrupted by a contentious (and apparently unscripted) panel discussion by “experts” from across Europe about whether Beethoven’s legacy is properly served by treating it with reverence; they conclude by lifting their glasses and drinking a toast to their own cleverness before the obsequious host informs us that we have been watching a program titled “Drinks Over Breakfast.” Kagel’s satire could hardly be more corrosive—and yet the music itself, deathless even in the most scandalous context, floats over Ludwig Van like a cloud of perfume, incorruptible and serene. Kagel never made another feature, but Ludwig Van is enough to secure his place as a filmmaker: It stands alongside Huillet and Straub’s Chronicle of Anna Madgalena Bach and Ken Russell’s Lisztomania as one of the great films about what it means to be a composer.

By the early 1980s, as the resurgent Right swept to power across the West, Kagel had become the official, state-sanctioned provocateur of German music (sealed with a specially created position at the Cologne conservatory), and his work seemed to lose its fangs. He had become less interested in shock tactics and more devoted to a form of musical exploration that we have come to know by the pejorative term “postmodernism,” creating new pieces by rewriting the music of yesteryear—Bach, Brahms—and combining disparate elements from the past into a new form of musical criticism. His later work could hardly be mistaken for anyone else’s—in 1982 he wrote “Szenario,” a score for string orchestra and whining dog—but pure balls-out anarchy, the determining element of his early music, was no longer what one could expect from a new Kagel piece. By 1998, when he won the Erasmus Prize—the Nobel of the European art world, past recipients including Marc Chagall and Charlie Chaplin—he was no longer an enfant and certainly no longer terrible. However, even in the early days of this century, when state support for the avant-garde was at its lowest ebb (so far), Kagel managed to remain a central participant in the world of European art music. Speaking with Coleman in BOMB, he said that in 2002 he had written a work called “The Tower of Babel,” describing it as “a piece for solo voices without accompaniment in eighteen different languages and with eighteen different melodies.” He added, “Perhaps this is my way of reflecting on Judaism.”

Abigail Miller is Tablet Magazine’s art director.