In 1885, a Lithuanian Jew named Barnett Rosenberg left his hometown of Devinsk, hoping like many Jewish emigrants to avoid conscription into the brutal Russian Army. His plan was to go to America, but by the time he made it to the port city of Hull, England, his money had run out; so, like a small but significant group of Russian Jewish émigrés, he found himself settling in Britain instead. If Rosenberg had managed to keep going to New York—or if, like two of his brothers, he had opted for South Africa—he probably would have found a better life than the one he eked out as a peddler, first in Bristol, then in the Jewish East End of London. But British literature would have been worse off. For his eldest son, Isaac Rosenberg, was to become one of the greatest English poets of the First World War, and perhaps the first Jew to gain a secure place in the canon of English poetry.

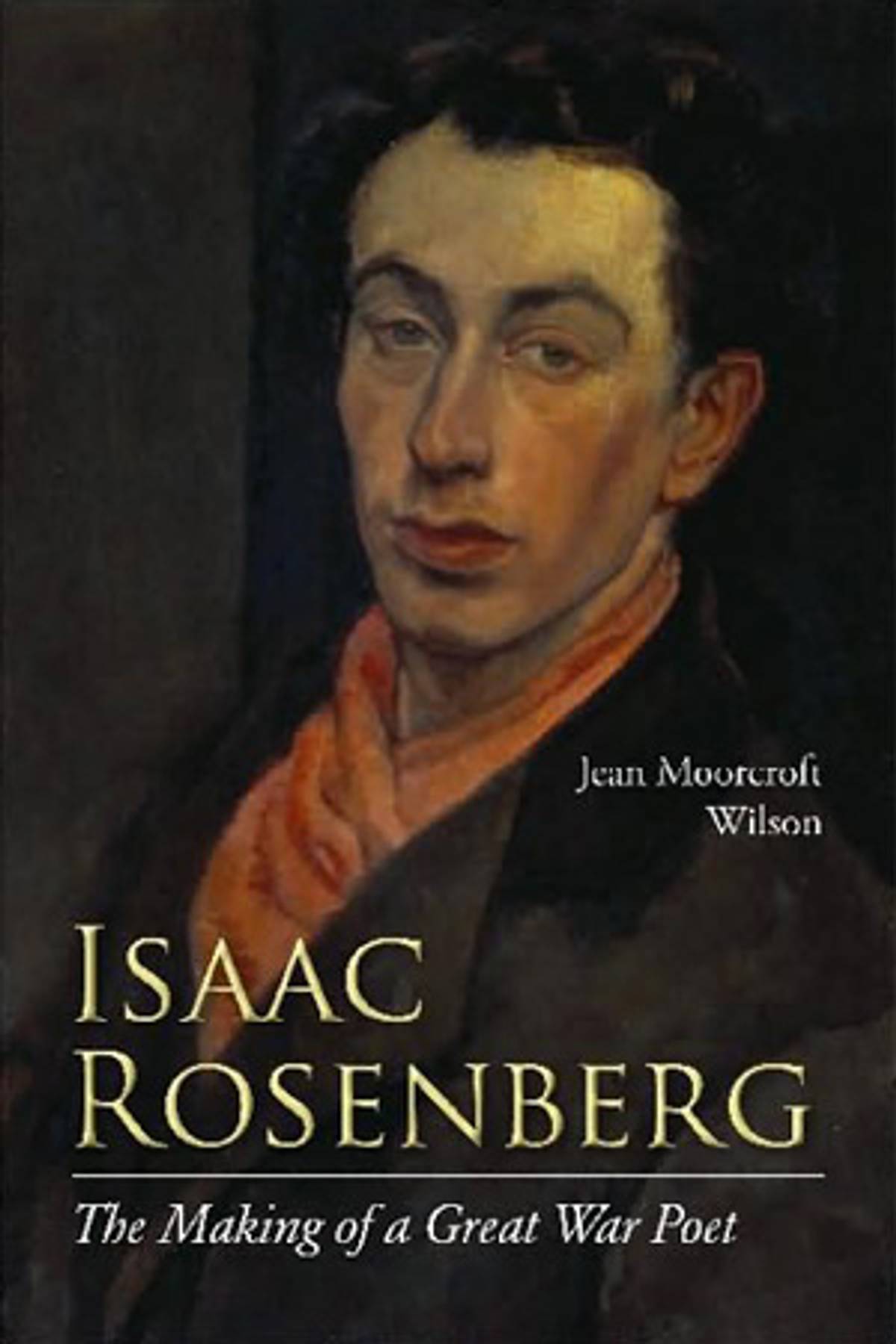

Reading Jean Moorcroft Wilson’s excellent new biography Isaac Rosenberg: The Making of a Great War Poet (Northwestern University Press), however, the ghost of Isaac Rosenberg’s American life—the life he never got to lead—is continually before the reader’s eyes. What would have happened to Rosenberg’s genius had he been born in the Lower East Side instead of the East End? He would have started out equally poor, no doubt—New York’s Jewish slum was as deprived as London’s, and his father was evidently too private and intellectual a man to succeed in business.

But in New York, Rosenberg would have been surrounded by a vast and thriving Jewish community, in a city dominated by immigrants. He would have joined the great movement of Jewish writers and intellectuals into the mainstream of American life. One can picture him going to City College, living in the Village, marveling at the Armory Show (for he was a dedicated painter as well as a poet), writing for little magazines. Most important, he could have lived a normal lifespan, instead of dying in 1918, at the age of 27, in the killing fields of France.

Being born in England, for Rosenberg, meant a much more difficult, pinched, unconfident existence. Economic opportunities were fewer than in America, class mobility much harder to achieve, and Jewishness a much more significant barrier to cultural acceptance. Here, we are used to the idea that the children of immigrants, who grow up speaking foreign languages, can grow up to be great writers of English; we think of Saul Bellow and Arthur Miller in their Yiddish-speaking homes. Yet while we recognize the Yiddish inflections in their work, it would probably not occur to most American critics to say of them what Gordon Bottomley, a poet and a major booster of Rosenberg’s work, said of him: “Rosenberg was of a first generation to use our tongue, and so had no atavistic or subconscious background with regard to it—and that must have conditioned his freshness of usage.”

Wilson tends to agree that Rosenberg’s strikingly original approach to language” stems from the fact that English was, in effect, his second language.” But surely the hallmark of the late learner of any language is an excessively cautious and conventional style, an attempt to assimilate” in speech. Rosenberg’s experiments in verse, like T.S. Eliot’s or Ezra Pound’s around the same time, ought to be credited to his genius, not his background.

In other ways, too, Wilson’s highly sympathetic biography also shows a certain lack of inwardness with Jewish culture, as when she suggests that Rosenberg’s predilection for images of female demons comes from the kabbalah—a highly esoteric tradition, even more so 100 years ago than today, of which Rosenberg surely knew nothing. She does not mention that, as Frank Kermode showed in his landmark book Romantic Agony, images of female vampires and incubuses were commonplace in the literature and art of the turn of the century. It is not too far from Wilde’s “Salome” to Rosenberg’s “The Female God”:

Queen! Goddess! Animal!

In sleep do your dreams battle with our souls?

When your hair is spread like a lover on the pillow,

Do not our jealous pulses wake between?

….

Our souls have passed into your eyes,

Our days into your hair,

And you, our rose-deaf prison, are very pleased with the world.

Your world.

Yet if Rosenberg was and remains an exotic figure in British literature, as Jewish writers are not exotic in American literature, this is not to say that his genius went without encouragement. On the contrary, Wilson shows that he attracted patrons throughout his life, both individual and institutional, Jewish and non-Jewish. He was one of a group of eager young people who congregated at the Whitechapel Public Library, built in 1892 by a philanthropic Protestant vicar for the benefit of East End Jews. Many members of the so-called Whitechapel Group—which Wilson describes as a poor, Jewish version of the Bloomsbury Group—went on to fame, including the painters Mark Gertler and David Bomberg. Rosenberg himself won admission to the prestigious Slade School of Art, his fees paid by one Mrs. Harriet Cohen, a wealthy, assimilated Jew who lived in the West End, not the East.

And when he decided, correctly, that writing and not painting was his true calling, Rosenberg’s poetry won the support of leading poets and editors, including Edward Marsh, the founder of the so-called Georgian school. Even when he was in the trenches of the Western Front, Rosenberg could count on encouragement from Marsh, who took time from his duties as Winston Churchill’s private secretary to critique Rosenberg’s poems. Another Georgian poet, R.C. Trevelyan, responded to news of his death this way: “For me it will be one of the cruelest things which this cruel war has done. None of the younger writers … were his equals in imaginative power.”

The terrible irony of Rosenberg’s life is that the war that silenced him also gave him his greatest inspiration. “Personally, I think the only value in any war is the literature it results in,” Rosenberg wrote, in a quotation that appears on the back cover of Wilson’s book. And the group of poems he wrote in France in 1916-18 rank among the most valuable documents of the First World War—visionary, grotesque poems like “Returning, We Hear the Larks,” “Break of Day in the Trenches,” “Louse Hunting,” and “Dead Man’s Dump”:

Earth has waited for them

All the time of their growth

Fretting for their decay:

Now she has them at last!

In the strength of their strength

Suspended—stopped and held.

What fierce imaginings their dark souls lit?

Earth! Have they gone into you?

Somewhere they must have gone,

And flung on your hard back

Is their soul’s sack,

Emptied of God-ancestralled essences.

Who hurled them out? Who hurled?

Of course, Rosenberg was not saying that a war is justified by the literature it produces. On the contrary, few people knew better than Rosenberg how terrible the Great War really was. For unlike almost all the other major English poets to serve in the war—Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, Siegfried Sassoon—Rosenberg was not an officer but a private, which meant that he was exposed to the full awfulness of army life. From the moment he enlisted in October 1915—not out of patriotic motives, as he insisted, but simply for the money, so he could help support his mother—Rosenberg complained about the indignities and deprivations the common soldier had to put up with.

During training, the food was so bad that soldiers almost starved: “one felt inert and unable to do the difficult work wanted,” he wrote. The enlistment bonus he was counting on for his mother was not paid. And then there was the anti-Semitism: “Besides,” Rosenberg confided to one Jewish correspondent, “my being a Jew makes it bad amongst these wretches.” He did not fight back in person—all his life, he was shy and proud, holding himself apart from would-be friends as well as enemies. But he had his victory in the poetry that was the product and the vindication of his tragic life:

Moses, from whose loins I sprung,

Lit by a lamp in his blood

Ten immutable rules, a moon

For mutable lampless men.

The blonde, the bronze, the ruddy,

With the same heaving blood,

Keep tide to the moon of Moses,

Then why do they sneer at me?

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.