Love, Death, and Poetic Madness at Dia

My encounters with Carl Andre

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 2012, I was at a birthday party in the East Village when I was introduced to a tall slender Frenchman named Philippe Vergne. He was the director of the Dia Art Foundation.

I asked Philippe what he was working on at Dia, and I was shocked to hear that he was putting together the first major American Carl Andre retrospective in decades.

The grin on Philippe’s face behind his thick-rimmed glasses combined with his swoosh of combed strawberry blond hair and his French accent, confirmed that he was a true daredevil. “It feels risky,” he said, earning my immediate trust.

I told Philippe about myself: I was a poet; secretary to John Ashbery; freelance art writer; adjunct art school professor; and very experienced editor of unintelligible texts for the highly respected but hardly read Swiss art journal Parkett.

Within minutes we were getting comfy up at the bar, with our backs to the party, which is when I realized I was being interviewed for a job. “Dia is looking to hire a new director of publications,” said Philippe.

After our second drink, I began to express to Philippe that I had been obsessed with Carl Andre’s poetry ever since I met Julian Pretto in the early 1990s.

“You knew Julian?” asked Philippe with great enthusiasm, knowing that Pretto had once been very close to Andre, and had shown his work, before dying of AIDS in 1995.

“Yes, I did know Julian,” I said politely. “And Beauregard.”

“Beauregard?”

“His standard poodle.” I now had Philippe’s undivided attention, and respect. “The gallery was a few blocks from my first apartment on Thompson Street in Soho. It was in an unassuming, somewhat shabby storefront on Sullivan. I remember walking in and kneeling down to pet the very distinguished standard poodle when I was greeted by a man wearing an ascot and tortoiseshell glasses, who introduced himself as Julian, and the dog as …”

“Beauregard.”

“—he politely informed me that the artist was Carl Andre and he explained that the sculpture was typical of his methodology, which was usually the placement of square metal tiles into a grid pattern on the floor without any joinery whatsoever. Julian suggested that since I was a poet I’d probably enjoy reading (or seeing) Andre’s poetry. There was a limited edition book from 1972 titled STILLANOVEL. It could be found right around the corner at Paula Cooper Gallery. He got right on the phone and kindly set up a time for me to visit the gallery.”

I few days later, I told Philippe, I arrived at Paula Cooper. I was led to a table at the rear of the gallery and handed a pair of white cotton gloves. The director then delivered the poem in an archival box and I began to leaf through the delicate stack of 100 unbound typewritten sheets.

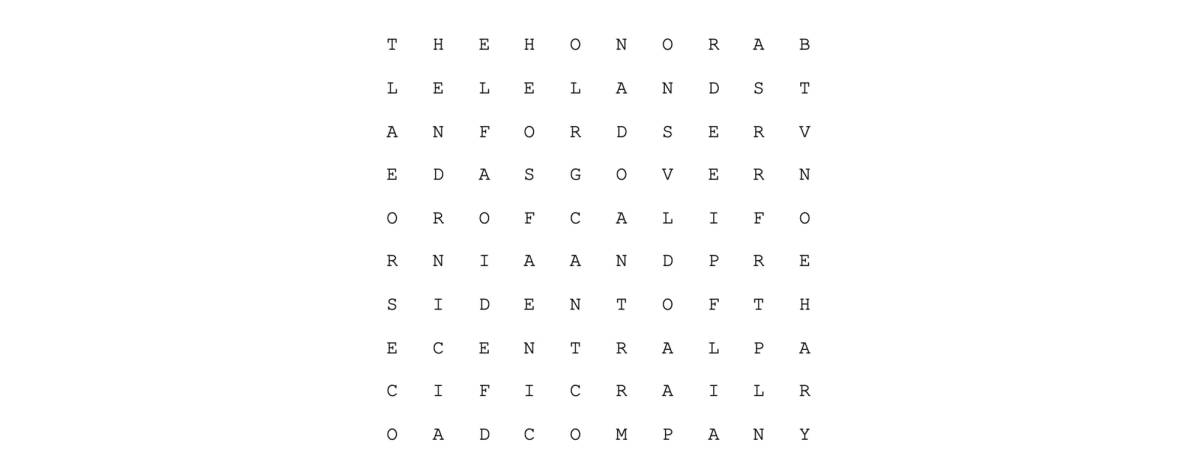

The pages were at first unintelligible—

After a while the gridded letters became much easier to decipher. “The honorable Leland Stanford served as governor of California and president of the Central Pacific Railroad Company.”

I flipped to another page.

.

“North Point dock about 1868 Eadweard Muybridge himself sitting on the dock.”

And I landed on another odd fragment:

“wife of Ea …” I assumed the next block of text would continue with the letters d, w, e, a, r, d. And so on, and so forth.

STILLANOVEL, I was surprised to discover, was a crime story about the influential 19th-century photographer (and pioneer of zoopraxography) Eadweard Muybridge, documenting among other things, the day he set out for Calistoga, California, to “confront the destroyer of his peace.”

The text was not written by Andre. He’d appropriated it from some other source. It told how, in 1875, after discovering a trove of love letters shoved in a drawer written to his young wife, Muybridge had tracked the man down at a poker game in Calistoga, pulled out a gun, and shot him dead on the spot. He then apologized for the disruption, and waited for the police to come and arrest him.

“Muybridge was brought into custody, given a trial, and acquitted. The murder was ruled a crime of passion, which was considered justifiable homicide,” I said to Philippe, who cut me off.

“Can you believe that Carl wrote that poem more than a decade before his own acquittal?”

It was as if we had run out of time. Philippe quickly said goodnight, flashed my Parkett business card, which he had in his hand, and told me he intended to contact me in the morning to make me an official offer.

The next morning I woke up with a hangover. I could hardly remember the night before. At first, I thought I had dreamed of an amazing conversation with the powerful director of Dia. Then it dawned on me that Philippe Vergne had, in fact, asked me to “come work at Dia,” where I would manage the Carl Andre book and build it from the ground up.

I made myself a pot of strong coffee, cracked open my computer, and Googled “Ana Mendieta.” Within a few minutes I was riveted to a New York Times obituary reading about the morbid and Gothic tragedy.

On Sept. 8, 1985, Andre had been high up on the 34th floor of his apartment in lower Manhattan with his wife, the Cuban-born performance/earthwork artist Ana Mendieta. They had only been married for eight months, but their marriage was failing rapidly. They were both heavy drinkers and had become embroiled almost nightly in intense verbal arguments. This particular fight escalated until the unthinkable actually happened.

Sometime after 3 a.m., Andre had frantically called 9-1-1, and sobbingly tried to explain. “My wife is an artist and I am an artist and we had a quarrel about the fact that I was more exposed to the public than she was … and she went to the bedroom and I went after her and she, um … went out of the window.”

When the police arrived, Andre phrased the story a little differently (perhaps more soberly), stating that after watching a movie and getting very drunk, Mendieta had gotten up to go to bed and insisted that he come with her. But he’d declined. He then added: “if that’s what she wanted, then maybe I did kill her then.”

What? A confession that he drove her to suicide? When I’d first heard about Ana Mendieta’s death, years ago, it was before the internet had become widely used. I knew the details were unsavory, but I’d only heard the version put out there by Andre’s galleries and supporters. No wonder Philippe had refrained from addressing the event. Did I really want to go to Dia to build this brute’s book?

I Googled another article stuffed full of unsettling details. Apparently, Carl and Ana had put away numerous bottles of champagne and watched a romantic comedy from the 1940s staring Spencer Tracy. Then, at around 3 a.m., Ana went to bed. When Carl finally went into the room, about an hour later, she was nowhere to be found—which is when he noticed that the bedroom’s sliding-glass windows were open. Carl offered this:

“It had been balmy, like eighty degrees, and the temperature went down to about sixty all of a sudden. What Ana did was get up and start closing the windows, because cold air was blowing in. Ana had to climb up—she was, you know, barely five feet. To close those windows you had to do it from the middle, so they wouldn’t jam. And in trying to close those windows she just lost her balance.”

I then read still another more tabloidy article—this one highlighting gory, descriptive details that hardly seemed believable: Andre had been found alone in the apartment with an abundance of deep scratch marks on his face, as if he’d been clawed by a jaguar. And questionable testimony had been given by a doorman, who had heard a woman screaming for her life in the middle of the night (“No! No! No! No!”), moments before an audible thud was heard on the rooftop of the neighboring bodega. In this article, the paramedics, who described finding Mendieta dressed only in her underwear, claimed that she’d landed with such force that her body had left an embossment.

Andre was booked and incarcerated at Rikers, and bailed out a few day later. After a three-year investigation, and a bench trial (sans jury), a Manhattan judge ruled Mendieta’s death a suicide.

The art world was, and still remained, divided. (In all fairness, human beings deal with trauma in a variety of different ways.) Andre’s dealers, collectors and many fellow artists stood behind him. People close to Mendieta refused to believe that she could have jumped, knowing that she had always had a terrible fear of heights. Nor had her closest friends noticed any signs that she was suicidal, let alone depressed. She was, on the contrary, in a positive frame of mind, having just won the prestigious Prix de Rome and been offered a one-woman show at the New Museum, for which she was actively gearing up.

Further down the rabbit hole I went. Much had been added to the internet since Mendieta had died, and her biography and work were mind-boggling. Not only was she born in Havana, as I’d known, but she’d been forced to flee at age 12 and seek political asylum in the U.S. under the Cold War resettlement program, Operation Peter Pan. Her father, Ignacio Alberto Mendieta de Lizáur, had been high up in the pre-communist Batista government before it was overthrown by Fidel Castro’s communist revolution. He’d actually had a long personal history with Fidel, whom he’d met in law school and worked with during his rise to power—before a falling out led him to fear for his family’s (as well as his own) safety.

On my subway into work at Parkett, I wondered: Was it out of the question that Ana had been defenestrated by a force other than her own will or the will of Carl Andre? And let’s not forget that Andre did, after all, spend a year at Fort Bragg, home of the Special Forces and the military’s Psychological Operations, aka PSYOP, division, after being groomed at Andover.

When I got to the office I sat down at my desk and did another Google search: “Che Guevara, assassinations in America …”—not a word of any attempt to stalk or kill the family members of political dissidents who had fled to the U.S., 20 years after Cuba’s revolution.

The story grew more bewildering and uncanny, though, when I began to view Mendieta’s mature work. In Mexico, some years after her formal art education in the States and before meeting Andre in NYC, she produced a series of remarkable, poignant works known as Siluetas, or “earth body” sculptures.

Produced throughout the Yucatan peninsula, these were haunting silhouettes of the female form made in, on, and with the earth, often including her own naked body fully or partially buried in mounds of dirt, smeared with blood, or coated in mud, feathers, flowers, etc.

The works created a perception of ancient human sacrifice. Some were more brutal than others. The most famous Silueta portrayed the artist laying naked under a blood-spattered sheet topped with a dripping cow’s heart.

My phone rang. It was Philippe Vergne. Was I free tomorrow to drop by his office at Dia to meet the senior staff?

About a month later, I was settled into my small new office on West 22nd Street. Although I knew immediately that the job was too corporate for my taste (it was my first “real” office job), I was thrilled to be reading Andre’s poems, and excited to play a role in presenting them to the world.

Early on, I came across Andre’s 1972 poem “Yucatan” and I was reminded of Mendieta’s interest in Mayan mythology—particularly that of Ix-Chel—goddess of the moon.

Generally rendered in glyphs as a woman-jaguar, Ix-Chel was said to have been the most beautiful young goddess in the sky.

She seduced the most powerful but temperamental god, Kinich Ahau, and they married. One day, suspecting that Ix-Chel was having an affair, the almighty Sun God became engulfed in jealousy and hurled his young wife out of his majestic castle of clouds. Gulp.

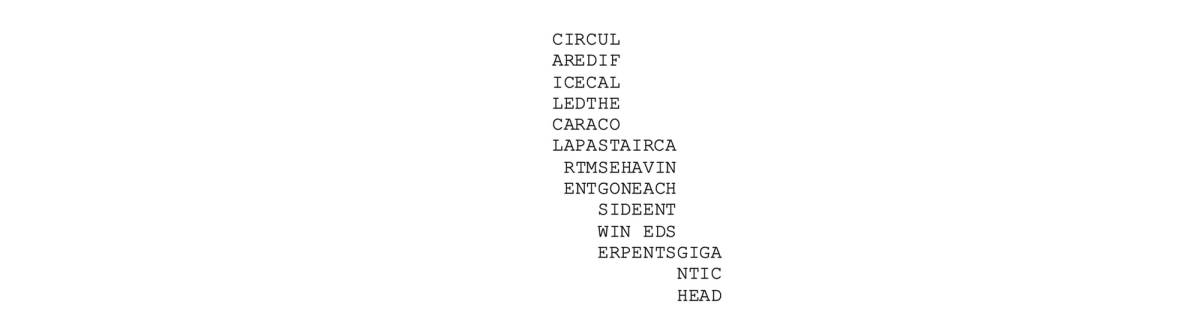

In Andre’s poem “Yucatan,” written seven years before he would meet Mendieta through their mutual friends, the artists Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, Andre set out to explore a different version of the same Mayan history—not by hiking across the Yucatan, but by traveling to the local library, where he discovered the classic 19th-century anthropological study Incidents of Travel (1848), written and illustrated by the explorers John L. Stephens and Frederick Catherwood.

Andre made a multipage poem using text from the book’s contents page—namely chapter 27. On one page of the poem, a stack of words (all in capital letters) appear like steps of the El Castillo pyramid at Chichen Itza, with a “GIGANTIC HEAD” having bounced down to the bottom.

Some chapters of Incidents of Travel describe a famously brutal aspect of ancient Mayan civilization—a sporting event played with a decapitated human head, as well as a ritual at a mysterious, sacred location near Chichen Itza, deep within the forest, at a natural sinkhole called Sacred Cenote. The Mayans considered this site (not unlike the abandoned granite quarries of Andre’s hometown of Quincy, Massachusetts) to be a passageway to a sacred underworld. Stephens refers to it as “an immense circular hole” where “human victims were thrown.”

I thought back to STILLANOVEL in an effort to make sense of all the anti-mimesis (life imitating art—a term coined by Oscar Wilde to invert Plato’s original thesis that art imitates life). I felt like I was rushing to earn an Andre/Mendieta Ph.D. in three hours. The pressure was on.

I eventually discovered a plausible origin for Andre’s unique title: the Italian word stilenovo, originally used to describe the Florentine poet Dante Alighieri’s “sweet new style” that used Italian vernacular to refresh the traditional Provençal rhymes of the troubadours.

No longer concerned with entertaining and flattering nobles with songs of knight errantry and coy (and often naughty) courtly love, in Dante’s early-14th-century poetry he sought to convey his very own, deeply personal search for divine love through his sustained heartache for the beautiful muse of his dreams, Beatrice, aka Bice—a graceful young lady his own age whom he first laid eyes on at age 9, though they never actually met.

I recalled a very important detail from Canto V of the Purgatorio section of the Divine Comedy—another evocative crime story involving jealousy, a brute king-figure, suspicion of adultery, defenestration, and uxoricide, and/or suicide. Dante wrote of a woman named Pia de’ Tolomei, born to a noble banking family in Siena, and married to a man called Nello in 1295. He was the Tuscan ruler of Maremma (a coastal town near Siena) and came to suspect that his wife was having an adulterous affair (sound familiar?). He locked her in a tower.

Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

And then what happened? Some say she starved to death; others say she jumped to her death; and still others say that Nello (or perhaps two of his henchmen) climbed the turret to Pia’s cell, held her upside down by her ankles, and dropped her out the window.

La Pia returns as a ghost, reminding us of her fate:

Please remember me, who am La Pia.

Siena made me, in Maremma I was undone.

I reached for my copy of 12 Dialogues, 1962-63—the iconic 1980 Nova Scotia College of Art and Design publication reproducing hand-typed conversations between Andre and his old Andover prep-school buddy, the experimental filmmaker Hollis Frampton—and pulled it off my bookshelf, remembering a page where Andre and Frampton had exchanged a playful, erudite volley concerning the swashbuckling 16th-century English courtly poet and nobleman Sir Thomas Wyatt. Andre ironically referred to Wyatt’s most famous “little lyric,” “They Flee From Me.”

Like all of Wyatt’s womanizing works, “They Flee From Me” was not published during his lifetime, and is still shrouded in mystery and falsities, but today it is commonly interpreted as a veiled confession of one adulterous relationship, among many. Taken at face value, it is a meditation on the concept that the times were-a-changin’. Essentially, whereas once the protagonist of the poem was accustomed to women seeking his intimate company, they now fled.

After an evening of particularly “special” romance that should ostensibly have kept the woman coming back for more, Wyatt realizes that she may have wanted more—but not from him. She would do as he had always done, by following her own bold search for the next sexual conquest. Though the poet is wistful, he is also impressed by her “newfangledness.”

Wyatt closes by wondering “what she hath deserve.” It is the line that leaves us all hanging.

Peel back another layer. It must be noted that Wyatt—playboy poet of the high court of King Henry VIII—was, at one time, rumored to have been intimate with the maiden Anne Boleyn.

According to lore, when King Henry VIII was in the market for a second wife, he’d sensed some competition and had Wyatt sent away to Italy, giving him the opportunity to tie the knot with Boleyn. By the time Wyatt returned to England, the king had become distrustful (if not paranoid and delusional), and had imprisoned his wife, along with a host of imagined suitors, in the Tower of London. Wyatt soon joined the crowd. Though Boleyn and others were executed by way of decapitation, Wyatt, by some miracle, kept his head. He was acquitted.

If, as many suspect, “They Flee From Me” is an autobiographical poem about Boleyn, I thought, we can interpret Wyatt’s question about “what she hath deserve” as literally asking whether his audacious paramour might play the field so well as to deserve a place at the top? And deserve to live like a queen and reign over an entire society? And deserve to live the life of any other wild philanderer? Or deserve to die?

And then I found the sentence I’d been searching for, where Andre types to Frampton: “One effect the great poets have on us is to leave us wondering. They do not fulfill our expectations. Rather they indicate that there is more to this world and this life than we had hitherto dreamed of.”

As co-editor of the exhibition catalog Carl Andre: Sculpture as Place, I intended to build a case for Andre’s much delayed entrance into the canon of 20th-century literature. On the surface of things, he could be called the founder of the “bureaucratic school” (a term I was batting around in my own head), but I had a hunch there was more to it. Andre was a secret romantic, a crypto-Romeo poet.

But of all the interesting subjects that the curatorial team was pursuing, “Andre as crypto-Romeo poet” was not one of them—especially considering the death of Mendieta, which was still a very sensitive and contentious topic to both Andre personally and to various groups in the art world, who were less concerned with his reputation and more struggling to come to terms with the inconceivable loss of a rising genius, an active feminist, and the then-very-rare “exposure” of an artist of color.

Though I spoke my mind with conviction at many editorial meetings, my impressions of Andre’s clairvoyant, anti-mimetic, criminological, bureaucratic, romantic, distinctly American Gothic poetry were never embraced. I came to understand that my premise risked alienating not only Andre and all of his affiliated fans, but many additional power brokers and gatekeepers (and potential lenders of artworks to the exhibition), for it required probing and encouraging an open debate about Mendieta’s horrific death, as well as Andre’s “inculcation” (to use his word) into English romanticism, his “vainglorious” personality flaw (to use another of his words), and the long history of passion crimes in poetry going all the way back to antiquity.

A discussion of Andre and romanticism (and all of the other subjects I listed above) would inevitably veer away from the formal aesthetic discourse around minimalism, and would become messy and seriously touchy. Tropes associated with the English romantic poets—including alcohol and opium addiction, prostitution and the contagion of syphilis, colonialism and Orientalism, heartbreak, madness, suicide, drowning, homicide, theft, atheism, eloping, burial alive, the city, chance, the dandy, the flaneur, phantasm, adultery, pedophilia, homosexuality, drowning, moonlight, lakes, fog, hikes, storms, motors, wind, fire, flight, Prometheus, revolution, mountains, abolition, and the sublime—were all, more or less, off limits.

At Dia, since any talk of Mendieta was strictly forbidden, Carl’s biographical details from the ’80s and onward were left unspoken or greatly deemphasized.

Soon, many, if not all, of my colleagues saw me as a book editor who was bonkers and behaving like a private eye. Indeed, I did nothing to hide the fact that I was using my amazing access to classified documents (unpublished poems) to excavate the real “@” (the symbol with which Andre had signed his artworks for decades).

Perhaps I was just being myself, a rogue poet, doing what I often do, despite my better intentions—create doubt, suspicion, laughter, and mutiny while gleefully daring the same people who hired me to undermine me and ultimately fire me.

But how could I ignore the fact that Andre always defaulted to the ideals of romanticism when discussing his art and poetry? When asked to go on the record, he regularly returned, with plenty of nostalgia, to stories of poetry in his childhood. In one interview, he said:

Poetry was a very common experience in our family. My mother was sort of a secretary of the mothers’ club of our church, and she would write wonderful poems in rhyme. My father, although he could write beautifully, preferred reading poetry out loud. I would be sitting on my father’s lap after dinner, and he would read Shelley and Keats, and other English Romantics.

In another article he added that his father would often give him a sip of sherry while reading to him, which developed in him a taste for that, too—a sherry-Shelley cocktail?

The poets who had originally captured his imagination were the ones who traversed the countryside, penetrated the natural world, and placed their indefatigable protagonists, equipped with epic demons and drives, in pastoral settings with unquenchable landscape lust.

One day early on, I went to lunch with Philippe. We ordered a bottle of wine, and I told him about my time in Marfa, Texas, in 2006, when I’d had the opportunity to sink my teeth into a major Andre poem. It was actually an unbound “book” of poems from 1963, titled one hundred sonnets.

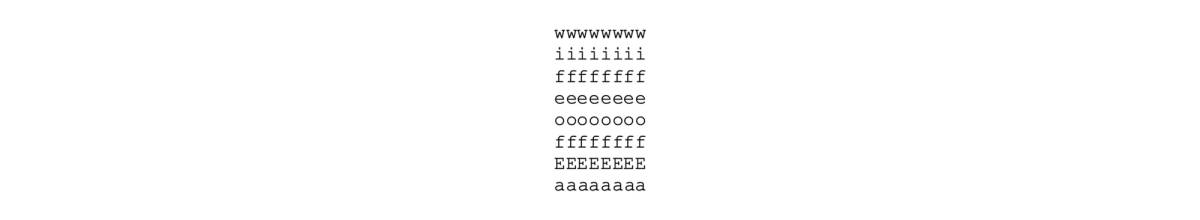

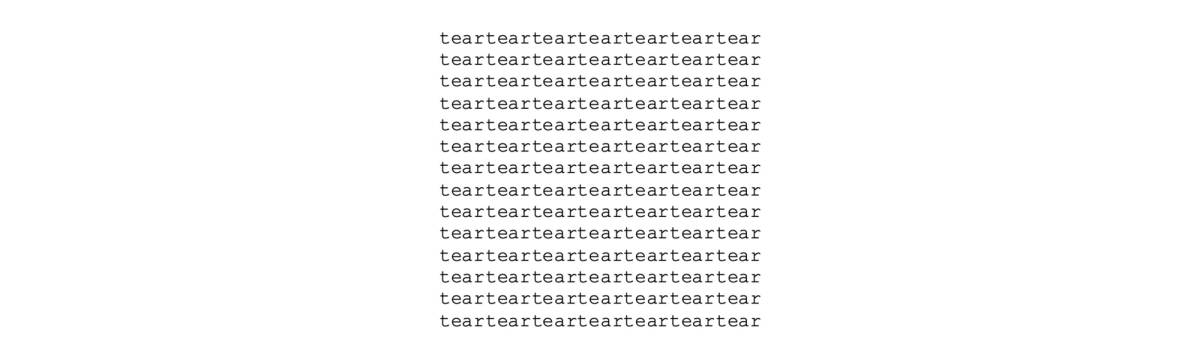

I’d been in Marfa for a one-month poetry residency at the Lannan Foundation. On my first day in town, I’d made a pilgrimage to Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation, a short bike ride away from my adobe cottage, and been thrilled to come across Andre’s sonnets, installed in a series of tranquil, empty galleries, laid out in long, birch plywood vitrines. Each page featured a single sonnet, composed of a single repeating word. In keeping with the rules of Petrarch, each had exactly 14 lines.

The longer I stared at any one poem, the more each word began to blur into a screen of pulsating, interlocking ink, beneath which sat a sheet of white paper. What began as one word repeated many times broke down into other words, or dissolved into no words at all.

For example, in one sonnet, “tear” (like teardrop) morphed into “tear” (to rip), and then morphed into “ear,” and into “art.”

The 100 sonnets contained seven pronouns (I, you, he, she, it, we, they); eight colors (black, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, white); 10 numbers (zero, one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine); nine elements (carbon, sulfur, copper, iron, silver, gold, lead, tin, and mercury); 19 nouns describing nature (sky, sun, moon, star, cloud, wind, rain, snow, sea, wave, tide, river, earth, rock, sand, sod, tree, grass, flower); two creatures (bird, fish); and 31 anatomical parts (head, hair, face, ear, eyes, nose, mouth, lip, chin, neck, shoulder, arm, elbow, hand, thumb, finger, chest, breast, nipple, belly, groin, genitals, buttock, anus, thigh, knee, calf, ankle, foot, heel, and toe). Six more words bring the human body (or bodies) to life (breath, blood, urine, sweat, piss, shit), while seven more imbue these figures with emotions (tear) and an attitudinal libido (cock, prick, balls, fuck, arse, cunt).

But what did it all add up to? An orgy in the grass under the moonlight’s watchful eye?

Each time I returned to Chinati to meander through the silent rooms filled with these indifferently attractive pages, my original thoughts on Andre’s Passion returned. The total culmination of the sonnets expressed, with just a long list of words, the struggles of carnal desire. The poem was indeed flowering, as its subtitle, “I … flower,” typed front and center on the book’s title page, promised. They may have been scrubbed clean of iamb, quatrain, turn, or couplet, but their crypto-cadences escorted the reader out the door into the sublime storm of nature and the inner turbulence of man’s natural emotions.

Philippe seemed interested, but did not exactly encourage me to pursue this angle.

Back at the office and keen to continue my universally unpopular inquiry into Andre as a closet romantic (or crypto-nympho), my first intuition was to compare him to William Blake, who was not only the father of English romanticism, but an artist. I discovered a 2016 lecture at the Blake Society in London, where psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist spoke of Urizen—an artwork (and poem) showing a character with a quill pen in one hand and an engraving instrument in the other, demonstrating Blake’s ambidexterity and ability to simultaneously and symmetrically use all his senses to work in two genres: one visual, the other verbal.

It struck me that Andre’s typewritten, concrete poems were a form of printmaking in and of themselves. According to Blake scholar Michael Phillips, Blake was “not a Shelley, or a Wordsworth, or a Keats with a fine quill pen and ethereal thoughts staring up to heaven and glancing through his manuscripts and leisurely leaning back and contemplating what he’s written and then passing it to his publisher to put it into press. Blake was a mechanic.”

And it was true. Andre was a mechanic, a typewriter poet and sculptor of metal plates. And yet, for me, Andre also had much in common with the “ethereal” romantics—the Shelleys, Keats, Wordsworths, and Byrons—because one hundred sonnets, despite its lack of fluid harmony, allowed the reader to assemble its clastic parts into a lush, pastoral that bloomed in the mind.

I thought of Percy Shelley’s 1815 poem “Alastor,” which describes a poet:

Roused by the shock he started from his trance—

The cold white light of morning, the blue moon

Low in the west, the clear and garish hills …

I reflected on the fact that in many nocturnes, the moon guides lovers to a place of privacy (or a place where they might accidentally be caught in flagrante delicto). But no matter how discreet, or indiscreet, the lovers tend to imagine themselves being observed by an omniscient eye. As, perhaps, in one hundred sonnets, the moon shines down on secret acts of lust, or functions as a chaperone with its flashlight in the sky taking lovers on a hushed erotic encounter.

But the strongest emotions of romantic love are often associated with stormy weather—not just moonlit swells, but raging gales of passion. Andre once said: “The disease of poets and painters, is that they tell me of eyes and heads and misters and bulls when I am interested in wind, rain, snow, hurricane. Id est: Goddamn it! Things happen.”

Things do happen! And certain artists, composers (think Wagner), and poets may even seek extravagant pain as a font of inspiration. In all tempestuous relationships, lovers break hearts. Even when things are going according to plan, the heart can hemorrhage. Codependency and obsession may take over. In the game of love, people do get hurt.

When I returned to Andre’s description of himself as a young child, listening to passages of Shelley while seated on his father’s lap, I could imagine the kinds of stories he heard and the valence he developed for the “things that happen.” In Shelley’s last long poem, “The Triumph of Life,” he writes of moving about “lily-paven lakes mid silver mist” transformed into a “living storm.”

In 1966, Andre installed his Equivalents series at Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York. He described the effect of this installation, which featured eight low-lying arrangements of firebricks as being like “stepping from water of one depth to water of another depth” and “wading in bricks.” In a 2012 interview, Andre said that Equivalents was conceived while he was canoeing in New Hampshire, taken in by the “the calm, even surface of the water at the lake.”

It was from this point forward that Andre began to think and compose horizontally, ultimately making history by disengaging sculpture from its vertical paradigm. If the plates of metal could be regarded as abstractions of a “calm” lake, I reasoned, then Andre himself should be seen as a sort of alchemical lake poet.

I immersed myself in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Lake,” which ponders “the terror of the lone lake” and the ominous, alienating surface that ultimately reveals very little about what may, or may not, lurk beneath.

And then Wordsworth’s famous “Boat Stealing: The Prelude (Extract),” in which he writes:

I dipped my oars into the silent lake,

And, as I rose upon the stroke, my boat

Went heaving through the water like a swan;

When, from behind that craggy steep till then

The horizon’s bound, a huge peak, black and huge,

As if with voluntary power instinct,

Upreared its head. I struck and struck again,

The poet turns back and finds relief from the dopamine spike of desire under a willow tree:

With trembling oars I turned,

And through the silent water stole my way

Back to the covert of the willow tree;

Finally, I considered Lord Byron’s “Manfred.” This classic Byronic hero—a pathetic, brooding, selfish, romantic outlaw—remained irresistible to me. Manfred (a stand-in for Byron himself) has apparently murdered his wife, Astarte. Secluded in the Alps, he is tormented by guilt, struggling to find peace of mind:

Must crimes be punish’d but by other crimes,

And greater criminals?—Back to thy hell!

Thou hast no power upon me, that I feel;

Thou never shalt possess me, that I know:

What I have done is done; I bear within

A torture which could nothing gain from thine.

Manfred eventually confesses: “I loved her, and destroyed her … Not with my hand, but heart …” Didn’t this sound familiar?

Shortly after I started at Dia, I was invited up to Buffalo to the home of Will Faller, stepson of the late Hollis Frampton, who had died in 1984—one year before Andre and Mendieta had married and also one year before she had died. My reason for going was to inspect Frampton’s extensive archive of Andre poems from the late 1950s and 1960s. Andre, as a matter of procedure, had sent Frampton a carbon copy of nearly every serious poem he’d written during this era, presumably for safekeeping. I could hardly believe that I would be the first editor ever to unpack this collection of archival boxes and peel open the neat manila folders within.

As expected, the archive revealed a poet who had found a way to hide emotions and sentiments, successfully cutting himself off from typical expressions of love and angst. Yet in numerous pieces the poet’s essential melancholia was deeply moving. One poem, in particular, spoke to me. It excerpted lines taken from a biographical interpretation of the last days of the American modernist Hart Crane, leading up to the moment, in 1932, when he drowned at sea in the Gulf of Mexico.

In this poem, six vertical chutes drop down the page with the deadweight of words. One chute reads: “I’m not gonna make it dear I’m utterly disgraced.” Another line trails off into the abyss, with the captain’s remarks: “if the propeller didn’t grind him to mincemeat then the sharks got him immediately.” Each of the lines reads both as a final statement and, visually, like the last air bubbles to leave Crane’s nostrils as he plunged in pure heartache:

“All right dear good bye.”

Several months later, about midway through my work on the Andre catalog, a message was forwarded to me from a woman named Alexandra Truitt, daughter of the late minimalist sculptor Anne Truitt. She was calling about some archival materials that Andre had left in her possession years before.

Days later, I rented a van and traveled with two colleagues to pick up this mysterious trove, returning to Dia as the sun was setting and the last office workers were clearing out for the evening. I put on a pair of white cotton gloves and began to carefully unpack the dozen or so boxes, removing one large stuffed envelope after the next. Each packet was filled with an assortment of black-and-white photographic prints, contact sheets, or negatives.

I opened an envelope that contained photographs of Andre’s earliest, blocky, wood pieces (“exercises” they were called) and remembered the phrase, “I was sketching with the radial arm saw,” which Andre had said in reference to the body of work he produced during the summer of 1959, when he had returned home to Quincy. His father, a marine draftsman and a skilled carpenter, had kept scrap wood in his basement workshop, alongside his power saw. In his spare time, Andre had used his father’s saw to shave away geometric voids in the various rectilinear solids he found lying around, as if he were carving primitive totems.

So I almost fell out of my seat when I pulled, from one of the last envelopes, a photograph of the actual radial arm saw. In 1959, Andre had gone so far as to name the machine, endowing it with the power not just to “saw” but to “see.” He chose “Beautiful Dreamer”—clearly a nod to the 1864 parlor song “Beautiful Dreamer Serenade”—the last song, a lullaby, written by the composer Stephen Foster, and published just after his death.

When he wrote “Beautiful Dreamer,” Foster was down and out. His wife had left him. He was alone in New York, living somewhere down on the Bowery, drinking himself into the gutter. He died at just 37. Some speculate his premature death was a botched attempt at suicide. In his wallet, a little scrap of paper was discovered. Was it the beginning of a suicide note? “Dear friends and gentle hearts.” The song’s first verse goes like this:

Beautiful dreamer, wake unto me,

Starlight and dewdrops are waiting for thee;

Sounds of the rude world heard in the day,

Lull’d by the moonlight have all pass’d a way!

The song was ravishing and haunting. But what did it mean? On the one hand, it has often been interpreted as a serenade to a dream girl, in which the optimistic singer attempts to lull this beauty away from the rude world and into his own sparkling universe.

But some read “Beautiful Dreamer” as a metaphor for a pessimistic if not devastated poet who mourns his dead (or lost) lover, and who knows that he cannot possibly bring her back to life. She can only exist in his memories, fantasies and dreams. Now he must wake up every morning and face the rude and the real world, and live another brutally lonely and disappointing day apart from his love.

In the end, I was fired. Philippe asked me to join him in his office. The HR employee Dia had hired (I think just to deal with getting me out), came in, sat down, and said something about the “learning curve.” Philippe was silent. No French accent, no visible daredevil. My borrowed time had expired. I had not been tamed. I had not been hushed. My only demand in severance was that I retain the title of co-editor on the colophon of the completed book. Philippe acquiesced with a nod of approval, and HR assertively asked me to pack up the belongings in my office and leave immediately.

They sent in one of the art handlers to help me with my books (including all back issues of my generally unread but exquisitely edited Swiss Parketts). Like in a free fall through gravity, my sense of time and place instantly collapsed. I’d known it was coming, but was still shocked by the cold, corporate indifference.

I went the next day to visit Andre in his infamous, original apartment—no longer as a representative of Dia. At least, like me, (persona non grata) he was his own person and his own poet. I brought an expensive bottle of champagne, as instructed. We got a little drunk (he was pretty obliterated, to be honest, on just one glass of bubbly ), and we stood side by side, looking out the 34th-story window. As always, he was wearing his blue workman’s overalls with the ubiquitous pencil tucked into his breast pocket, his round pink cheeks flushing and under his jaw line his iconic, Amish-looking gray curtain beard. I guess we were two baby-faced boys, guided by ancient muses, trying to make it and make it new (in the Pound sense) in the rude (in the Foster sense) world. I guess I needed closure, as clouds crossed the sky leaving lower Manhattan in a giant gray shadow. I think it was important that I finally admitted to myself that Dia, and my hubristic ambitions there, were the enemy, and not necessarily Carl, who may have been acquitted but may not have been absolved. Who may, like Manfred, have been tortured by guilt.

I could now see all of my thoughts reflected back to me in Andre’s window. It had to be a textbook case of what Harold Bloom proposed in Anxiety of Influence to be “poetic misprision”—a creative misreading due to the reader’s desire to be the author and to narcissistically project onto the poem, and then extract from the poem, his own sense of things in order to own the poem and own the poet’s autobiography.

I now could see that it was I, not Andre, who was the true romantic, lost in time, exiled from the court, using my own sad “saw” to cut through the darkness of the past and to “see” presently, with the “beautiful dreamer” blade (in my mind), to mill and drill and shave away excess and finally reveal the skeletal bones behind this enigma, and these phantoms.

It could only be my ongoing fantasy, triggered by my trauma, and so I brought Ana and Carl (like Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde) into my reality. I stole them, but only long enough to understand them—to grasp the archetype of an impossible love—to see them and comprehend them in their epic moment of uncontrollable rage and irreversible transgression. Yes, to even perhaps stare voyeuristically, lucidly, into the machinations of a precise moment that even Carl—who was perhaps in a drunken blackout, or eclipsed by repression, or inhabited by an unwelcome intruder (MKUltra? Fort Bragg?)—had never seen with his own eyes.

Why did I want to see them fighting at the window, high up in a balmy misty Manhattan, at that extreme moment when a beautiful life was sucked into death, lost forever from breath?

Ana Mendieta was the lifeless muse calling me to come and see for myself; she was the beautiful dreamer of my song. It was Ana (or the ideation of Ana) haunting me—she had woken in me to speak through me, about one shocking evening when, like La Pia, she was undone.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.