A Charmed British Life

A recent biography of Tom Stoppard shows the playwright coming to terms with the Jewishness buried beneath his proud English identity

“Happiness is … equilibrium. Shift your weight.” The dots floating in the middle of the first utterance are nebulous, generating uncertainty. The monosyllabic instructions that follow assert balance.

Tom Stoppard quoted these lines, over three decades after he had written them, to Hermione Lee in her recent biography, Tom Stoppard: A Life. Shifting from foot to foot, he told her: “Equilibrium is pragmatic. You have to get everything into proportion. You compensate, rebalance yourself so that you maintain your angle to your world. When the world shifts, you shift.”

Tomáš Sträussler’s early life, however, was a panorama of upheaval. He was born in Zlín, Czechoslovakia, two years before the Nazi invasion in 1939, to a nonobservant Jewish family. Fleeing the Nazis, they ended up in the British colony of Singapore, where the Czech shoe company his father worked for had a factory. His father died, probably while under assault from Japanese forces, while the rest of the family were evacuated to India, where his mother, Marta, met and abruptly married an English army major on leave. They moved to England when he was 8.

At Okeover Hall, a “somewhat decaying” stately house where he went to boarding school, Tomás became Tom Stoppard, and put on Englishness “like a coat.” The tumult of the earliest years gave way to vistas of order and continuity. He was teased mildly over his pronunciation (of ‘s’ and ‘th’, and his rolling ‘r’), but although he was foreign, he “did not know it.” He would later reflect that the England he fell in love with during this time was “in the first place, only a corner of Derbyshire, and in the second place, perishable.”

Ken Stoppard, a “clean-cut Englishman” with a “strong commitment to King and Country,” taught his adopted son “to fish, to love the countryside, to speak properly, to respect the monarchy.” (The “slow, pleasurable concentration spent on an English river” was “part of his induction into Englishness.”) Later on, in “moments of hostility,” which included xenophobic and antisemitic outbursts, Ken would make sure Stoppard knew how much these moments mattered: “Don’t you realize I made you British?”

Her husband’s overbearing manner and “overriding Englishness” entailed Marta leaving her Czech past and language behind, along with her Jewishness. The emotional restraint of English life in their home helped to shed the past. “She felt that British chauvinism would put us children at a disadvantage among our new peers if much was made of her foreignness,” Stoppard later told critic Kenneth Tynan.

Behind the story of miraculous escape and good fortune, however, was a fraught courtship. Having fled Nazism and survived her husband’s death, Marta—then in her mid-30s, with Tom and his slightly older brother Peter in tow—was rescued from limbo in India by Ken’s assertive pursuit. Ken, who quickly proposed (she married without telling the kids) and urged resettlement in England, represented “safety and control,” in a situation where, as she put it, she had to decide on her own what she thought would be best for her family.

The vast majority of Stoppard’s family had been killed in the Holocaust. It is unclear whether Marta knew, at this point, what had happened to them, but she “said nothing” to Ken about it. (“I wept alone, after the war,” she wrote in a letter many years later.) In England, her new husband called her “Bobby,” and was “implacably uninterested” in her past, including the Jewishness that she would obfuscate. Marta retained her “strong Czech accent and Czech cooking,” but the family “did not much communicate its emotions or share confidences.”

Ken had a bitter temperament, founded in “poorly rewarded army service” and “class resentment.” He never abandoned his self-image as a gentleman soldier, represented in martial garb, as the middling sales manager at a machine tool manufacturer after his resettlement. He had a bullying manner and demanded subservience. Stoppard’s mother, on the other hand, was an “anxious, compliant, and dependent” figure in the marriage.

Hermione Lee does not explicitly analyze the question of the direct effect of Ken’s antisemitism on Stoppard’s attitude toward national belonging. But the way Ken leverages the fragility of his stepson’s Britishness against him colors Stoppard’s later gratitude and patriotism.

Marta was evasive and deflective when Stoppard and his brother asked if they were Jewish as kids. Her responses often called into question the inherent solidity of Jewishness as a group category (“well, two of my sisters married Catholics.”) The Sträusslers inhabited an assimilated context in Czechoslovakia, and she made the argument that she had only been “made Jewish” by Hitler and the Nazi invasion.

By banishing the interregnum of the Holocaust, Marta established continuity between the old and new versions of belonging that had provided—and might still provide—normality. Pointing to the banality of her previous state of assimilation, and the irrelevance of her Jewishness within it, became another way to validate and smooth her children’s entry to a similar status among the majority in Britain. Stoppard only found out with certainty that his family was Jewish—and that the vast majority of them were killed in the Holocaust—in the 1990s.

Fueled by his extraordinary professional success and a thriving family and social life, Stoppard’s feeling for England, a land of “tolerance, fair play, and autonomous liberty,” blossoms across Lee’s biography. But from his English perch, he would eventually become drawn back to the grand sense of continental drama from which he came, and in which many in the 20th century were still contained. Jewishness—his link to that world, and its demise—began to lap against the present with increasing intensity as his life went on.

Stoppard held chronic skepticism toward the very premise of biography, and an aversion to intrusion into his personal life and misrepresentation, both literary and political. These sentiments finally gave way to an invitation for Lee, a literary scholar and biographer, to write the book, which Stoppard issued personally at the end of a party he held in 2013. He was mostly cooperative with the process, which involved Lee speaking to a plethora of friends as well as accessing his personal materials, even though at times, she notes, “he clearly regretted setting this book in motion.” Upon receiving the draft, his only request was the removal of a reference to an actor who had been fired during a production. This nearly thousand-page tome is a tribute to the security and liberty that allow the recording of (almost) everything.

This is a mostly happy life, studded with triumph. There are glowing accounts of Stoppard’s magnetism, charm, good looks, thoughtfulness, kindness, sartorial elegance, and industriousness; his excellence as a friend and family man; his awards and knighthood and honorary doctorates and millions in earnings. Cruelty, despair and turmoil are scarce. The complications are on the margins of positive feelings and upward trajectories.

Stoppard treats personal duties and their representation in acts of commitment—commemorations, birthdays, funerals—with care, if not solemnity. He is unfussy and unhesitant in acting on behalf of friends at important times. He keeps in touch with Val Lorraine, who was his landlady in Bristol when he was in his 20s, for 50 years; she was one of his great encouragers as an artist in the early days. He goes to see her when she is dying in 2001, and the house remains “full of his traces.”

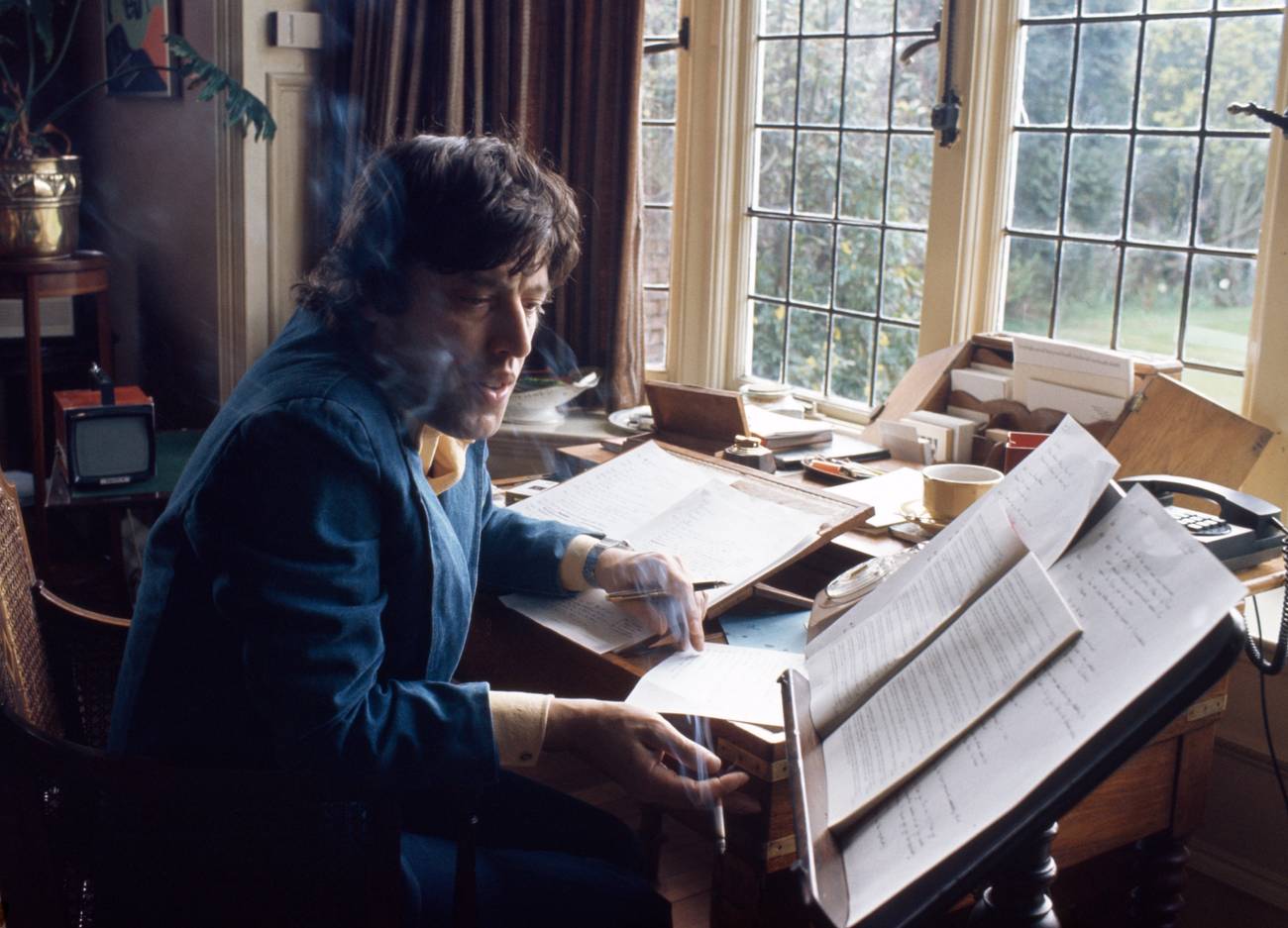

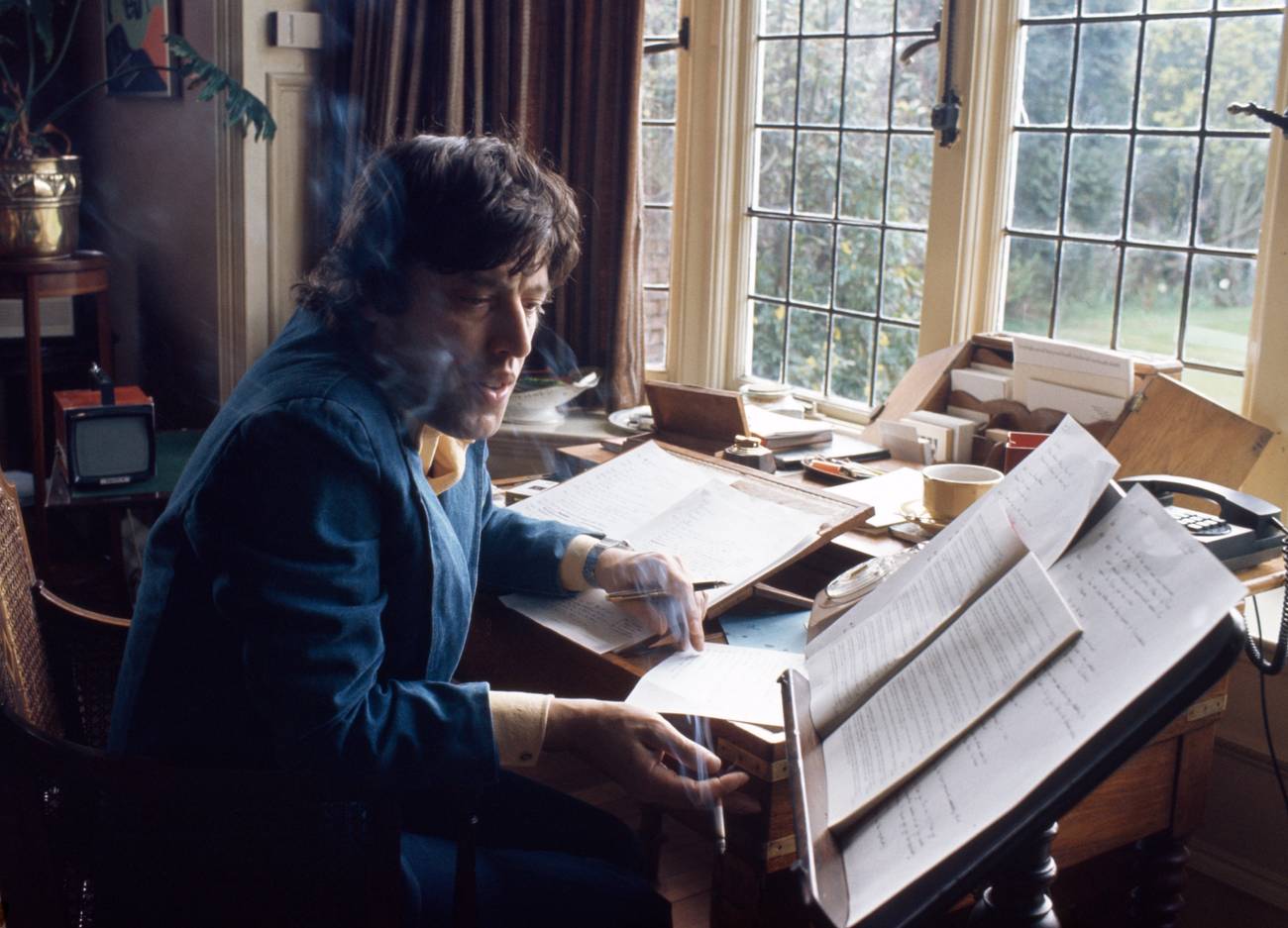

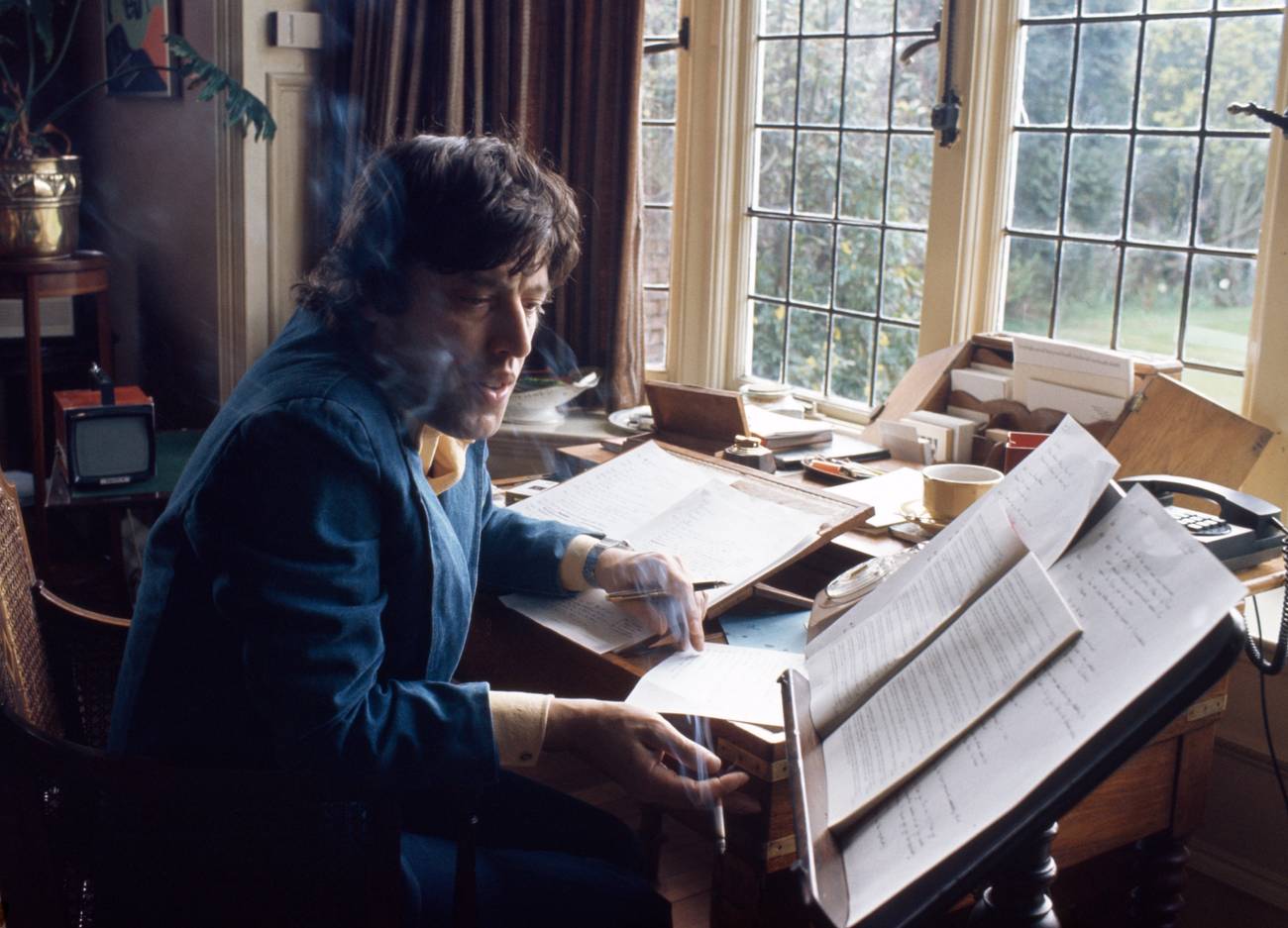

The engine of his productivity is unfaltering. Living in a shared house in his 20s, too broke to afford a lighter, he “cut the sandpaper off the match packet and glued it to the desk, so he wouldn’t have to put his pen down for a second, and could strike a light as he wrote.” Later, as “lord of his estate” at his country house Iver Grove, he was “kindly and benign” around his sons and their friends, but sat writing at the kitchen table into the early hours. The chutzpah of his ambitions, his deep sense of gratitude, his drive to maximize experience—these all feel grounded in a sense of how easily life could be taken away.

Stoppard embraces the commercial contract with his audience: “I am as square and traditional, let’s say reactionary, a person as you could hope to meet because I operate on the premise that a theatre’s job is to prevent people from leaving their seats before the entertainment is over.” But there is restless positive energy in terms of what might come from that commercial contract: “We mustn’t deny audiences the compliment, indeed the satisfaction, of having to keep up,” he tells the cast of Rock ’n’ Roll in the middle of the play’s run, attempting to eliminate unnecessary hesitations and pauses in dialogue.

Hermione Lee skillfully identifies the motif of “doubleness” in Stoppard’s life, and her understanding is especially acute in her treatment of Stoppard’s self-presentation in the various forms he must inhabit. In later reference to him “shedding his protective skin” in his mid-40s, she writes: “It had taken a long time to shake off the ‘bottled-up’ legacy of the family and school he had come from. And he continued to be quite in favor of bottling up.”

Lee has a gift for dramatizing moments in Stoppard’s experience by positioning them against the complex presence of his ensemble. Her account of the differing perceptions of an early dinner in which Stoppard does not intervene when Harold Pinter lashes out at his now ex-wife Miriam Stern, for example, is a masterclass in nuanced evocation. His eventual separation from Stern is “gradual, undramatic, and good mannered,” but Lee locates the pain in it, despite their ongoing friendship and elevated civility.

And her portryal of the private histories associated with places and homes, such as this elegaic account of Iver Grove—in which he lived with Stern, whose parents maintained Jewish rituals there, for over two decades—is sweeping yet intimate:

“The round stone sundial on the wall of the flower garden, with its design of pansies, reading ‘For Miriam who made this garden 1982,’ was never taken down. But the rare pansies vanished utterly, the murals on the garden walls faded and bleached, the water garden that took so much labour to make fell into disrepair. The big swirling energy of the Stoppard family life moved on, fragmented and reshaped itself elsewhere.”

Alongside the English sensibility, New York recurs throughout the book, auguring glamour, memorable exchanges, and an ever-expanding community of voices.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, Stoppard’s 1966 breakthrough success as a playwright, ran on Broadway for 420 performances and won Tony and New York Drama Critics Circle awards. On a trip to the city six years earlier, he had been sleeping on couches. In the summer of 1967, though, “he was taken up, spoiled and pampered.” He told his parents that he had performed “his Modest Young Englishman act” on television; in general, “everyone thought him witty, lovable and charming.”

Lee’s depiction of how the metatheatrical, structurally playful The Real Thing (1984) was received is bountiful with elation. Peter Shaffer and David Mamet and Leonard Bernstein loved it; Mick Jagger and David Bowie and Princess Margaret came to see it. “It was one of those nights at the theatre which makes you think about the way you have led your own life,” Lee writes. Producer Manny Azenberg proposed to his girlfriend the day after seeing the play, which had “seemed to make it possible” for him to get over his fear of divorcing again.

In New York, his experiences contained echoes of the European and Russian cultural experience from which he and much of his audience had come. (During the Rosencrantz run, he was often assumed to be Jewish; “I don’t know, there must be some Jewish, somewhere,” is one of his replies.) The line of Alexander Herzen in Stoppard’s 2002 play, The Coast of Utopia, “Being half Russian and half German, at heart I’m Polish, of course,” got a muted response in London, but in New York, it “seems to be a joke about almost a third of the audience.”

Stoppard had another American adventure in Hollywood. “There’s a difference between completely wasted time and time which would have been better spent,” he says in relation to screenwriting, a lucrative “detour” that Stoppard figured out how to mine. Lee charts several convoluted development sagas, the most successful of which was the Oscar-winning Shakespeare in Love.

It is Steven Spielberg, however, whose relationship with Stoppard represents a certain frontier of the playwright’s journey. Their engagement appears to have contained little of the rich warmth that is palpable in his friendships with Azenberg or Mike Nichols. Despite its relative impersonality, however, Lee’s narration of their work together contains intriguing glimpses into Hollywood in the 1980s and ’90s.

Stoppard did a lot of work on Always, provided uncredited lines for Amblin films like Hook, wrote dialogue for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and re-wrote one scene in Schindler’s List. He also wrote Empire of the Sun. More informally, he helped Spielberg choose scripts and was involved in the early development of projects.

Spielberg, who was in the habit of using many writers while maintaining separate bilateral engagements with each, was impressed by Stoppard’s bluntness. “It was unusual for Spielberg to meet a writer who stood up to him,” Lee writes. During work on Empire of the Sun, Stoppard wanted to “be faithful to the strangeness and harshness of Ballard,” and mocked the “heavy-handed pathos” of Spielberg’s approach. He sent a note responding mockingly to the schmaltziness of the ending: “Why don’t we give Jim a little dog at the beginning, and then the dog could show up too.”

While Stoppard was clear-minded about the discrepancies in their sense of taste, Spielberg found it useful to let him express himself freely and to harvest what he needed from the experience. The director ultimately characterized Stoppard as a “consistent blessing in disguise,” testament to how the playwright’s interventions were often productively disruptive.

During this period, of course, Stoppard was not officially Jewish. But Spielberg was quietly exploring his own instincts in relation to Stoppard’s perspective. In the context of Empire of the Sun, the director “thought that, although they never discussed it, Stoppard might have felt some identification with Ballard’s story, since he too was a ‘displaced person.’” Later, Spielberg—along with Stoppard’s other American Jewish friends—would describe Stoppard’s discovery of his Jewishness as “a key to his character.”

As an outsider who proudly became an insider, Stoppard celebrated those settled modes of Englishness about which the native English were rarely self-consciously explicit. “Even the most English of his plays,” writes Lee, “have the sense of an outsider at the edge of the English establishment, or an argument about what makes England or Englishness worth having, or a foray into an undiscovered country.”

While his instincts were at odds with a culturally ascendant left, they were deeply aligned with the feeling that the West could be positively redefined in light of the negative counterexample provided by communism. His relationship to right-wing politics, which intensified in the ’80s, was less about seeking an identity in conservatism than embracing the political corollary of an English, and to some extent broadly Western, identity.

Stoppard set verbal joust and jest—rooted in the innocence of prep school, and presented in the free associative community of theater—against the malevolent con of ideological oppression. The freedom to fuss over peculiars and particulars, and playfully self-undermining absurdity, was a state of intellectual bliss founded on the continuity and security of Britain.

Stoppard often set that sensibility against communism as an ideological system and against the governments that practiced it: “Unpredictable English eccentricity is preferred to an ideology which explains all mutations and tragedies as part of ‘historical inevitability’,” Lee writes of Hapgood and The Dog It Was That Died, which reflected Stoppard’s longstanding interest in double agents.

Describing the plays, Lee writes: “However ruthless, opportunist and grotesque the activities of the western intelligence operative may be, they are working in the interests of a preferable system. Englishness—here in the shape of public school education, small boys playing rugby, rule-breaking, eccentricity and linguistic richness—is worth defending.”

Stoppard’s direct involvement with conservatism as a political movement meant navigating a path through new milieus. He was a member, along with figures including Irving Kristol and Donald Rumsfeld, of the Committee for the Free World, and he co-signed an open letter to The New York Times endorsing the U.S. invasion of Grenada “to restore democracy.” He developed connections with Margaret Thatcher, whom he believed was “what the country needed” at the time (although he would later note her “philistinism and her divisiveness”). But he “did not labor the link between Marxism in West and Communism in East.” His focus was the “victims of ‘Soviet tyranny’.” There is much diligent work done on their behalf documented here: writing letters, sending money, speaking, petitioning, protesting, and so forth.

As Joseph Brodsky wrote, responding to a century marked by great upheavals, “Geography blended with time equals destiny.” Stoppard’s sense of his own status in relation to others, and his commitment to Soviet dissidents in particular, were defined by that perception. His baseline good fortune, he would reiterate, was that his mother “married into British democracy.” As Stoppard reached the pinnacles of conventional success, affirming the rationality of assimilation, he would “reclaim” the Cecil Rhodes line that “being born an Englishman was to have drawn first prize in the lottery of life,” quoted so often by his father.

The parallel versions of Stoppard’s self that clarified his good fortune were personified by Václav Havel. “A playwright whose mother didn’t marry into British democracy has been charged with high treason,” is how he recorded Havel’s 1977 arrest. Their instinctive friendship is one of the most robust described in this book. Encountering the absurdly overprecise invented language ‘Ptydepe’ in The Memorandum, designed by Havel to unmask the ambiguity-erasing obsessions of totalitarianism, Stoppard felt like “somebody was writing his play.” Their responses to politics, too, were conditioned by the sense that, as Havel wrote in The Power of the Powerless, absent totalitarianism and ideological warping, life moves towards “independent self-constitution” and the “fulfillment of its own freedom.”

Stoppard’s decision to become a public advocate on behalf of foreign lands and foreigners was strongly opposed by his mother and Ken. “I feel English and love England and have not an iota of feeling transplanted,” he told his mother in 1986, in an unusually strong letter, defending his anti-Soviet activism in response to her palpably anxious complaints (“Don’t make waves”). “I have no emotional feeling for Europe at all,” he continued, “except that I do think Communism is anti-human. I know it intellectually not emotionally.”

In one way, this is a book of forms—family, national identity, manners, positions, honors—and how Stoppard mastered them. In his role as a public figure he drew on the formality of his early years of schooling and instruction from his stepfather. But even as an increasingly decorated figurehead who came to represent a larger Western story, he was unable to find the right way to speak to his mother about the truth of their family.

The buried world of the past nonetheless repeatedly resurfaced. From his British remove, Stoppard surveyed the sweep of Central Europe to Russia: “There is hardly a time in his life, in fact, when he is not writing in some way about Europe and Eastern Europe, exile, journeying, and homelands,” writes Lee.

Stoppard’s immersion in the Viennese and Austro-Hungarian tradition led to adaptations of plays by Ference Molnàr and Arthur Schnitzler, and ultimately, his most recent play Leopoldstadt. The “sophistication, irony, cosmopolitanism, civilized intelligence, worldliness” of that world—and, Lee specifies, “in great part, its Jewishness”—were tremendously natural to him. He was able to inhabit a parallel track of history, in which he could have been a writer in “direct descent from Joseph Roth or Stefan Zweig.” “I was born in a town you could drive to from Vienna,” he specified to his friend Patrick Marber, who directed Leopoldstadt in London, in a recent conversation.

Stoppard pieced together his Jewish history in the early ’90s, through a series of conversations with various relatives. (By then unwell, his mother had been speaking to some of the same people for a few years, including the granddaughter of her sister killed in the Holocaust, but under strained conditions: Ken would not welcome her Czech family into their home.) The process was partly about discovery, and partly about confronting and acknowledging the full heft of what had been suppressed all along. His old aversion to questioning her, however, was still present. By the time of her passing in 1996, he had not delved into the details of his growing findings and connections with her, even downplaying his interest. After she died, his own passive participation in the process of suppressing the past became clear to him: Ever since his childhood, there had been an element of “almost willful purblindness” on his part.

At some level, the formative experiences of school, where he attended Sunday services and “being Christian was like being English,” still held sway. A new Jewish identity had not replaced that; he had no feeling of immersion in a new tribe. As soon as his mother died, however, Ken told him to stop using the name Stoppard, his deeply rooted antisemitism having been inflamed by Stoppard’s public support for Soviet Jews. Despite Ken’s attempt at de-Anglicizing his stepson by revoking the “honorary Englishman” status he had bestowed on him, Stoppard was awarded a knighthood in 1997. Ken died that same year.

Stoppard returned to the Czech Republic in 1998, “returning to his first home for the first time in nearly sixty years.” On a more extensive trip the next year, he was taken to the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague, which had been reopened after communism. He saw the names of the Czech victims of the Holocaust “grouped by their home towns,” including those of his grandparents, aunts, and other family members. While he was in the synagogue, Stoppard was “very quiet, took notes and did not show his emotions.” Having learned “the whole story” of his past, and come full circle through his visits, Stoppard reflected on the limitations of the journey. Remains of the past “have the power to move, but not to reclaim. Englishness had won and Czechoslovakia had lost.”

But in the years that followed, in a “late echo of his mother’s own survivor’s guilt,” a sense of “denial about his own past” crept up. He began to reconsider the “charmed life” tagline he had fixed to the miraculous origins of his British identity: “He increasingly felt that he should have been rueing his good fortune in escaping from those events, rather than congratulating himself.” This coincided with changes in his mental landscape: He was having nightmares about the Holocaust, and experiencing the return of “very early scenes and moments,” as if “he were recovering memories which had always been there.” Two decades after dismissing the remains of the past, “what had once been obliterated came back to haunt him.”

Mardean Isaac is a writer and editor based in London. Educated at Cambridge and Oxford, he has written for publications including the Financial Times, Lapham’s Quarterly and New Lines magazine.