Clothes for the Man Who’s Got Nowhere to Wear Them

A Gatsby-esque collection of shirts and ties speaks to the COVID age of sweatpants and sneakers

I once started a short story that began, “My father was the man in England who bought Jay Gatsby his clothes.”

I’d be surprised if anyone needed reminding of the reference. Gatsby is showing Daisy the contents of his hulking dressing-room cabinets, the massed suits and dressing gowns and ties. “I’ve got a man in England who buys me clothes,” he says, vaingloriously but maybe also half-apologetically, both for the plenty and the taste. “He sends over a selection of things at the beginning of each season, spring and fall.” It’s when he spreads out his shirts, of sheer linen and thick silk and fine flannel, “shirts with stripes and scrolls and plaids in coral and apple-green and lavender and faint orange with monograms of Indian blue,” that Daisy begins to cry. “Stormily,” Fitzgerald notes.

In my story, the father hears of Daisy’s tears and is angered, since he was the man who chose the shirts, that Gatsby should get all the credit. He decides he will sail to America, find Daisy, and introduce himself. Because I couldn’t imagine what either would say to the other when he found her, beyond her revealing to him her suspicion that Gatsby was a Jew—a suspicion which the father in my story already shared anyway—I didn’t finish it.

The argument for Gatsby’s Jewishness is a simple enough one to make. Only a Jew would be quite so smitten by a woman of Daisy’s class, and only a Jew would make such a megillah of a few shirts. Many a student essay has struggled to explain the reason for Daisy’s tears. But it isn’t hard to find. She’s touched by the immigrant naivete of Gatsby’s need to prove to her that he has prospered.

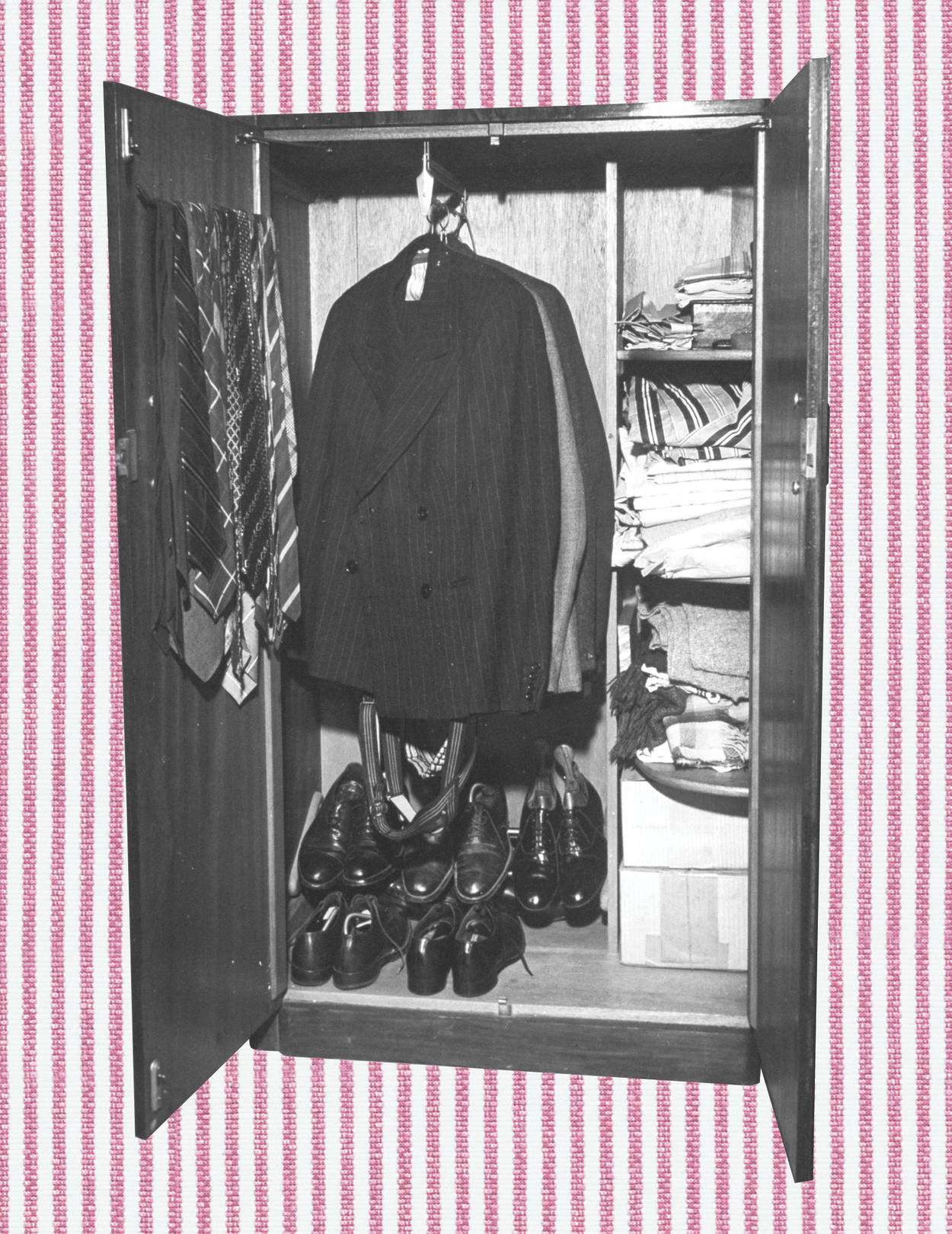

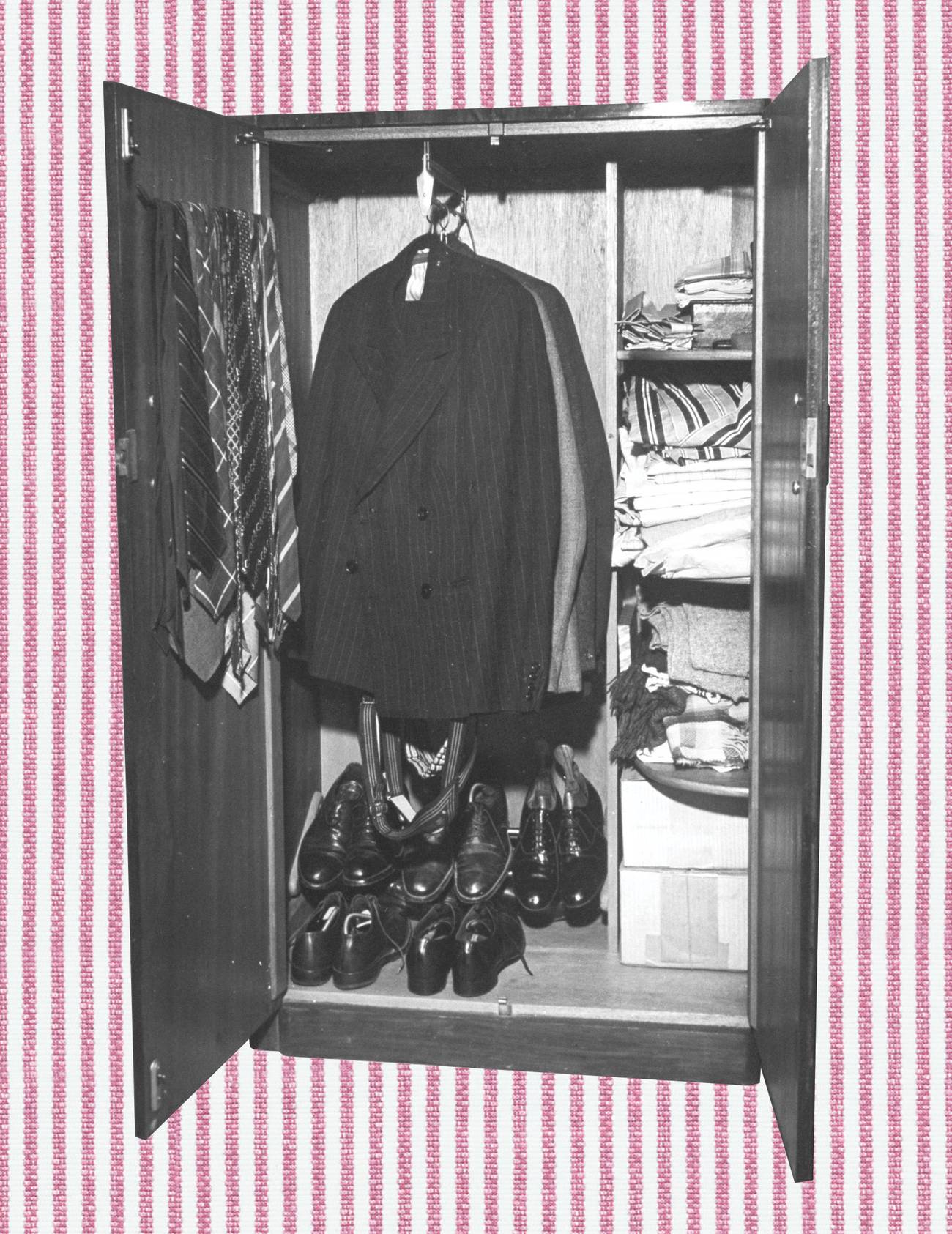

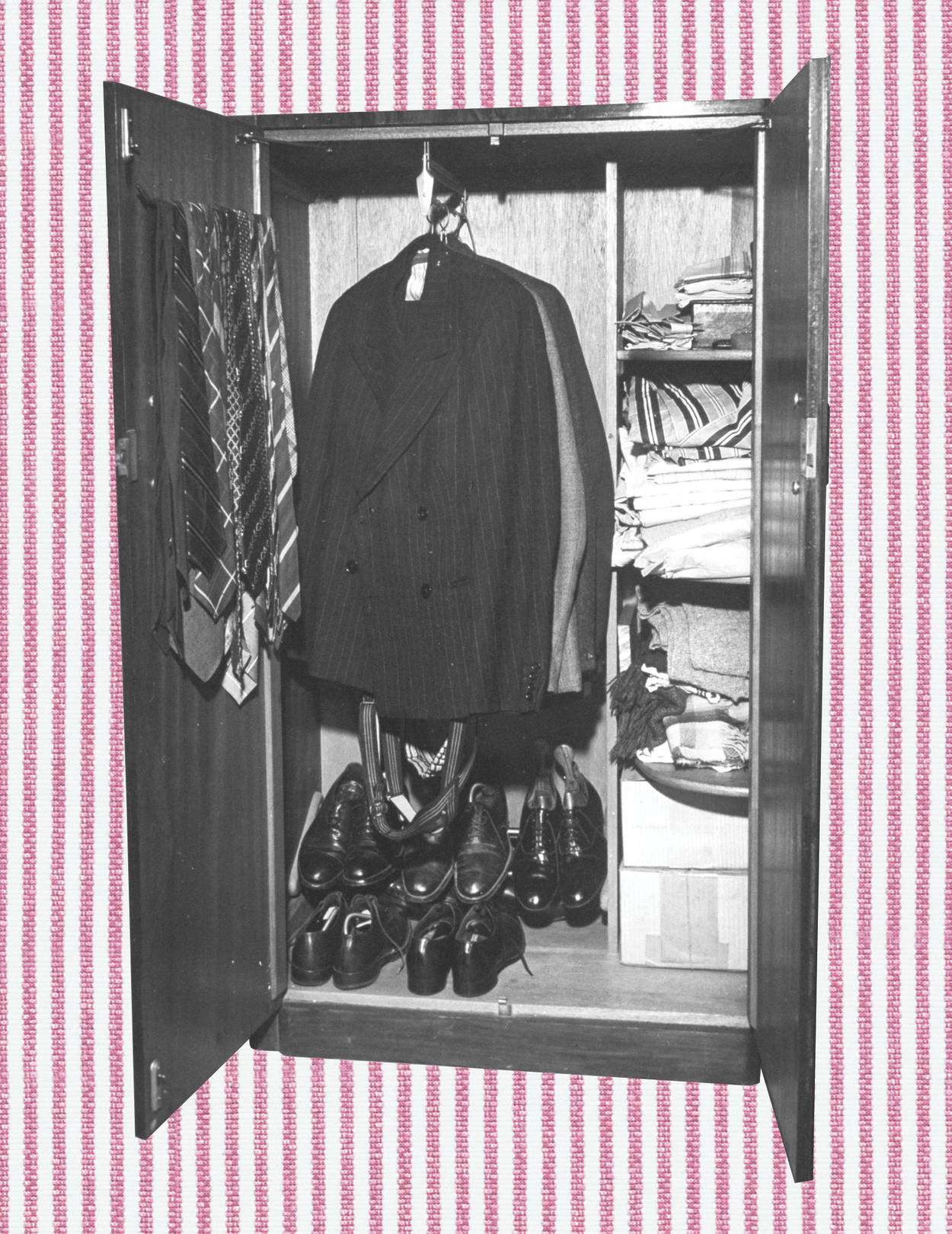

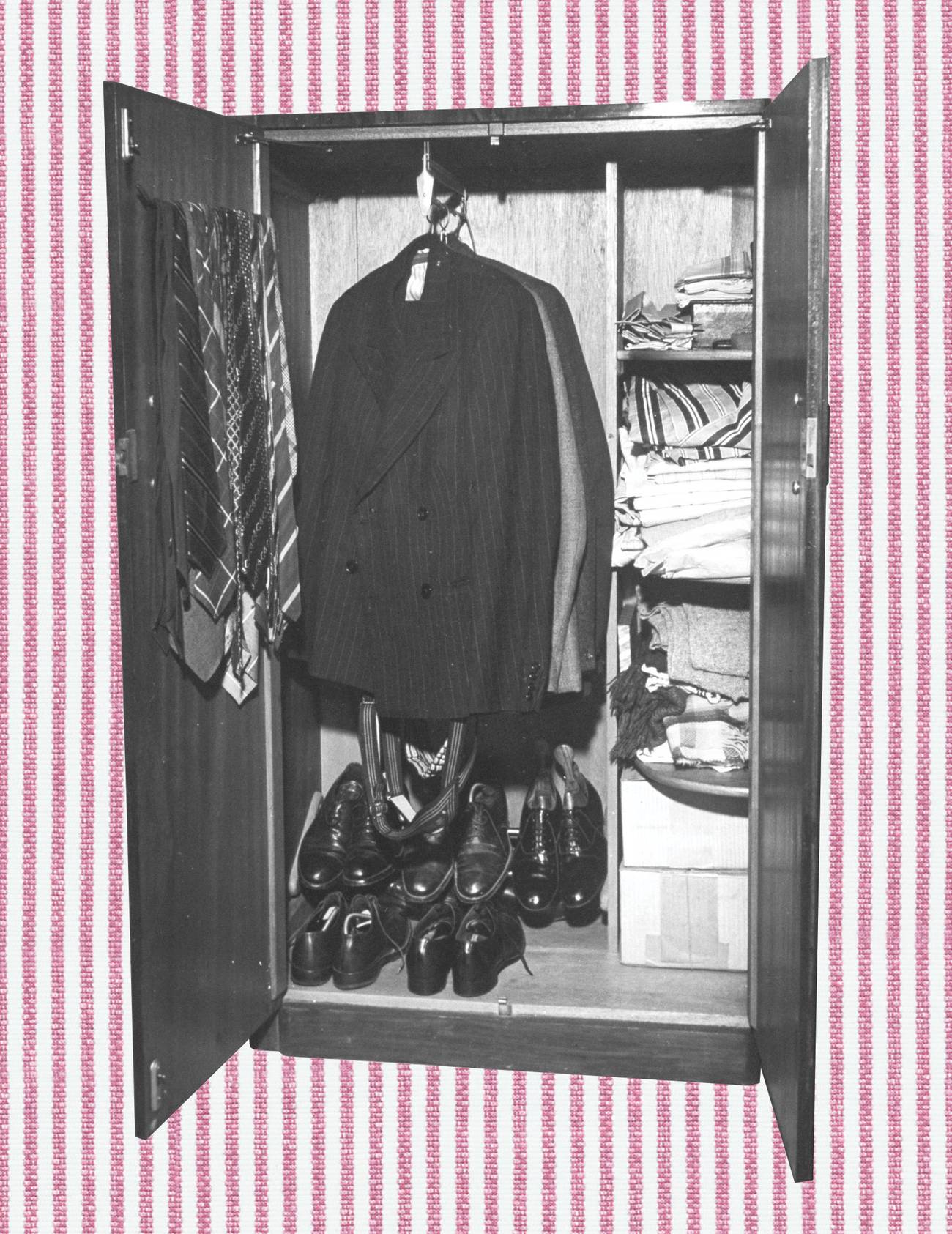

In Gatsby’s place, I would have done the same. I too, though I have no man to do the buying for me, have shirts by the cabinet-full. They wait, fiercely pressed, on wooden hangers, arranged in the first instance according to color (mainly they are white); then by fit (I don’t do skinny but I will consider generously tailored); then by style of collar (my preference is for classic pointed, the longer and more suggestive of Neapolitan Mafiosi the better, thereafter button-down, but never ever—in any circumstances—self-made city-boy cut-away); and finally by degree of stiffness, descending from petrified for weddings and bar mitzvahs to llama-eyelash-soft for candlelit dinners.

So many shirts do I possess that, pre-pandemic, I employed a person to refresh and iron them on a part-time basis, and periodically to make sure that those still in their boxes had not grown mildew. Today I dare not look inside the boxes. You will notice that I make no mention of Hawaiian or any other holiday shirts. None of the shirts I own are short-sleeved. I not only have no T-shirts with writing on them, I have no T-shirts full stop. Gatsby’s wardrobe, I suspect, was guided by the same principle: Though a Jewish man loves children, he has no ambition to resemble one.

Once you amass shirts, you must amass ties to accompany them. I own several hundred, which swing from oak and silver tie racks like lianas in a tropical rainforest. While my rows of readied shirts bespeak an embarrassingly obvious Jewish anxiety—what will I wear if I am suddenly invited to The Palace? How can I be sure they won’t mistake me for a peddler from Tomsk?—my tie collection is of another order of obsessive disturbance. Yes, it’s a species of hoarding; if I could empty the world of ties, I would. But there must be an element of bondage compulsion in it too, a memory of Abraham binding Isaac, and of course an apology for the thousands of meters of tefillin I’ve never laid. When I was growing up, I lived next door to a yeshiva bocher who staged false hangings of himself from the To Let gallows abandoned in the garden by the estate agents who’d sold his parents the house. He would stand on a chair, put a noose made of tzitzits around his neck, and let his tongue hang out. He was surprised I queried this. “How is it any different to you wearing a tie?” he’d ask.

I have not, in 50 years of tie-buying, thrown a single one away. The wide, Al Capone ties hang to the rear of my collection, relics of a more rollicking era, but I keep them for the time when their day comes again. Already, the skinny numbers I bought freely two years ago are looking etiolated. They were probably the last ties before ties vanished altogether, and mark the movement to end formality in men’s tailoring, but after the casualness brought on by the pandemic it appears likely we are going to want to look trussed-up again. Study the changing length and width of your ties and you have a picture of your age.

Trousers are a subject of their own, but briefly—to complete the inventory of my dressing room—I own about one pair for every three shirts, some with companion jackets, some not. Like most men my age, I long abandoned bell-bottoms but have held on to trousers with a single or double front pleat because I cannot believe there is a more flattering or comfortable style of trousers for men who like to rise from their writing desks and go directly to lunch. Flat fronts are not for writers, and if I make exceptions of Oscar Wilde or Tom Wolfe or Hunter S. Thompson, that is because they are not Jewish writers.

You don’t find many Jewish writers who are dandies, though I have always taken David Mamet to be one. The one time I was scheduled to share a platform with him in London, I found him in the green room playing honky-tonk piano in a black shirt and red braces, which threw me, as I’d read a prose paean he’d written to his favorite cashmere turtleneck sweater and, expecting him to be wearing that, I had gone out especially to buy one and was encased up to my carotid arteries in it. I can’t say it suited me. It made me look like one of those troglodytes Othello told an excited Desdemona about, men whose heads grew beneath their shoulders. And I itched beyond endurance all evening. How Mamet manages to sit through one of his own plays in a cashmere turtleneck, I can’t imagine. But I don’t doubt he looks dashing when he goes up onto the stage to receive his plaudits.

Otherwise, though Jews make good tailors, they don’t—or at least Jewish writers (excepting early Proust and late Kafka) don’t—make good tailors’ dummies. Saul Bellow’s bowties looked borrowed from generations of retired New Yorker art critics. Philip Roth dressed like a lapsed Jesuit. Woody Allen never departs from potting-shed schlemiel; while the fictional Larry David is not to be distinguished from the real Larry David in being of the golf-loving school of Jews who love zip-up cardigans, crew-neck sweaters, and T-shirts worn under T-shirts.

In Britain, Jews have not so far taken leave of their senses as to suppose that leisure wear will assist in their passing themselves off as gentiles, and no serious Jewish writer plays golf. But the pandemic has weakened our defenses. Until COVID-19 changed everything, I never owned what Americans call sweatpants, though I did once, in the course of training to be a table-tennis star, wear a tracksuit. Aside from the drawstring, however, sweatpants and tracksuit bottoms have little in common. In a tracksuit you sweat for real; in sweatpants you sweat for style. That I have found them comfortable and even becoming after being locked away in them for a year only makes me feel worse about them and about myself. Is there a would-be member of a country club hiding away inside me after all? Am I not the incontrovertibly alien, urban intellectual I thought I was?

What likelihood would you say there’d be of Daisy Buchanan crying stormily when I lay out my fleecy Reebok joggers and roomy, striped Ralph Lauren polos. “Is that it?” I hear her wail. “Is this all he has?” I could open my wardrobe and show her the cotton poplin Eton shirts with French cuffs swinging inertly on their hangers, like my yeshiva bocher friend on his makeshift gallows. Or give her one of my narrowest, silkiest Duchamp ties to run her fingers down. But an impression you have to try twice to make is a failed impression. There is no getting past the leisure wear. Yes, she might indeed shed a tear. But it will be for a lost illusion. “And I thought you were a Jew,” I know she is thinking.

Howard Jacobson is a novelist and critic in London. He is the author of, among other titles, J (shortlisted for the 2014 Booker Prize), Shylock Is My Name, Pussy, Live a Little, and The Finkler Question, which won the 2010 Man Booker Prize.