A Conversation With Donald Fagen

Talking Nabokov and Judaism with the Steely Dan co-founder, whose first live album comes out today

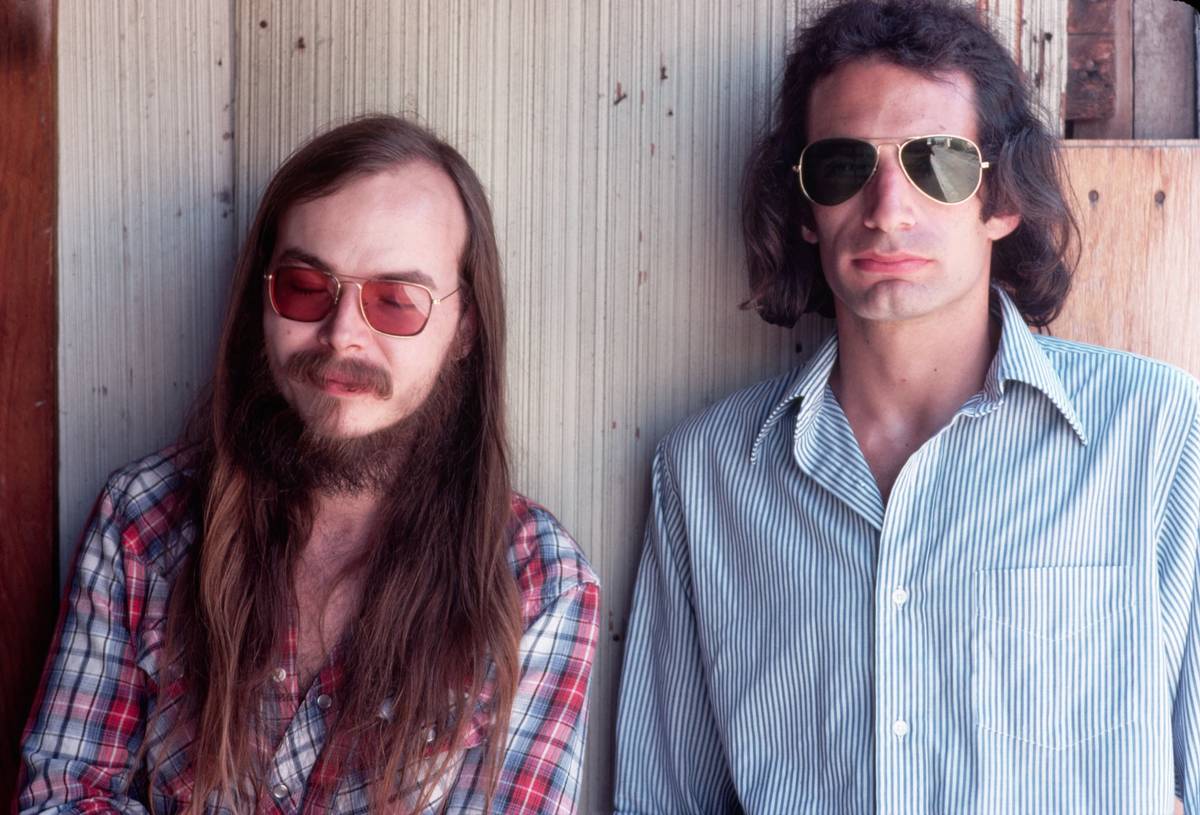

A few months before the lockdowns I got an email from someone calling themselves “Donald Fagen.” Surely this was one of my friends gaslighting me, yet I could not imagine any of them possessing even the basic coding skills required for creating a convincing fake email account. But it actually turned out to be the real Donald Fagen. A few years ago I’d written an essay in praise of Steely Dan’s 1980 masterpiece Gaucho, and he was checking in to say that he read it and liked it, thus putting me in contact with the mysterious entity that had presided like an oracle over my childhood. Eventually I got on the subway with my handheld digital recorder and we sat down for a few hours on the Upper East Side to talk about writing, recording, hi-fi, jazz, Dylan, science fiction, Nabokov, the anxiety of influence, and whether there is any culture left outside the COVID-celebrity-industrial complex. Among the greatest American songwriters of all time, Fagen remains at 73 an unmistakably distinctive mind and sensibility.

The memories of growing up in the suburbs of New Jersey on your autobiographical LP The Nightfly, and in your memoir, are so vivid: late-night jazz shows, early rock ’n’ roll on the radio, science fiction, Cold War paranoia. Somewhere, some basic longing to write and create was starting to percolate during these years.

Yeah, that’s right. When I met Walter [Becker] at Bard in the late ’60s we were really dissimilar in the actual circumstances of growing up, but we dug the same stuff. He knew all the references I did. Jazz, science fiction, comic novelists, what they called “black humor” at the time. John Barth, End of the Road, before he started to write these schizotypal sort of things. Bruce Jay Friedman, who edited a volume of black humor, is largely forgotten now, a very funny novelist, and actually preceded Philip Roth with that sort of Jewish humor. Edward Albee’s early plays. I think what all these writers had in common was a pessimistic view of human nature. And there were conversations in these novels that were almost supernaturally unfiltered. People would just say what they were thinking. That particular thing was something Walter and I picked up on and it was in the back of our minds when we were writing lyrics.

A tune like “Pretzel Logic” has a pretty elliptical story going on, and speaking of science fiction!

Well, yeah, that was kind of a time-travel thing.

It’s funny when the person who greets the narrator in the future, says, “Where did you get those shoes?” like the fashion between the two times is completely out of whack.

That actually fills in the link between black humor and science fiction, because the science fiction novels I liked the most were funny in that way. I think my favorites included that kind of humor. Like Frederick Pohl and his partner Cyril Kornbluth, who wrote these really satirical novels.

The Space Merchants was recently reissued in the Library of America Series …

Oh really? I remember reading that one when I was a kid.

Another guy from that era who I think of as funny is Alfred Bester.

Another one of my favorites. He was an ad man, so it’s got this very New York, Madison Avenue feel, the Mad Men type of thing, but making fun of it.

Your interest in science fiction has extended well beyond your youth. I know you’re a William Gibson fan.

Actually I just got the audiobook of his latest novel, Agency, love it so far. And I read Peripheral. I met him once, he came to a show. We’ve emailed a couple times. His emails actually are scary. I’ll write some normal little kind of joke or something and he’ll write back improving on my conceit, with like a lot of detail that I never would have imagined. [laughs] And this is just in an email.

The name of the bar in Neuromancer is the Gentleman Loser! [a lyric from “Midnight Cruiser” on Can’t Buy A Thrill]

Yeah, right!

The thing that’s very Gibson in Steely Dan is that it’s retro future … you’ve got these dystopic near-future settings that feel like the ’40s.

You get something like that in Nabokov’s Ada too, its also a retro future, it’s really a steampunk realm. There’s no electricity, there was like this jackpot event [alluding to Gibson’s The Peripheral], and all the phones work by water, hydrophones.

I don’t know too many people who’ve actually read Ada. I love it too.

Oh, I was obsessed with it. [Laughs] And the character Ada is annotating the whole thing! Once you get through those first few chapters, it’s straightforward enough …

Amazing to imagine him in that Montreux apartment suite writing up Ada from a stack of index cards.

I visited that place once. They take you in and you can see his bed and his desk and everything. [Laughs] Lolita was a huge bestseller when I was a kid, and everyone bought it but almost no one read it. My mother had a hardcover copy of the original edition and she may have started it but I know she never really read it. But I was, you know, looking for the dirty parts, but then I just got so far into it. I was a little too young to comprehend exactly what was going on but still I thought it was fascinating. Then I read it a few years later and thought that it was probably the greatest thing ever. I’ve read Pale Fire four or five times.

Another cool thing about “Pretzel Logic” is that each verse is an episode, almost like a chapter, with each chapter set in a different time.

Well, back to “where did you get those shoes”—if you were both funny and interested in time travel, that might be the kind of thing you’d come up with.

And at the same time it’s all made to fit the constraints of a 1-4-5 blues structure, but it’s a blues with really unexpected harmony.

Right. I mean a lot of that messing around with blues structures was just from listening to jazz records, where you often hear someone trying to juice up a blues. Monk did it. Miles did it.

A tune like “Straight No Chaser” is an obvious blues, but a really bent take on the blues.

Yeah. Arrangers used to do that too, with any kind of music really. You look for harmonic tricks, or you take it out of the key for a moment, just finding ways to make it more interesting. And there’s also what they call a “Charlie Parker blues” which goes through the cycle of fifths to get to the IV chord, and so on. There were a lot of chords in the way he would play through a blues.

There are also a lot of considered, elaborate, often exquisite guitar solos on your records. It’s almost like, to go back to Parker for a second, at the height of bebop in the mid-’40s, the tenor or alto sax was the “axe,” and then sometime in the ’60s, after Hendrix I guess, the guitar became the instrument for that kind of conspicuous virtuosity.

I guess because Walter and I were jazz fans we were bored by most rock guitar solos. We were bored by the limited chord structure, although I think by the time rock ’n’ roll became the country’s dance music, and because of rhythm and blues, the guitar was already there. If you hear a Bobby Bland record or a B.B. King record …

I put on the headphones and listened to Morph the Cat the other day and was struck by how everything is so clearly placed across the left-right spectrum. Do you think explicitly about arranging for stereo?

Walter’s father was a hi-fi freak, he was one of these guys who used to get a kit in the mail and build his stereo, and Walter inherited this hi-fi bug. I also had a kind of audiophilia, but the records I liked most were jazz records done in Englewood Cliffs by Rudy Van Gelder. I always noticed that with his stuff there was something about the way he recorded and mixed that was just strikingly perfect for the kind of music it was. Then also, Walter and I both, in the sort of beginning days of stereo liked this guy Enoch Light who used to make stereo test records. They were arrangements with huge separation between all the instruments, one called Provocative Percussion I remember, and Walter and I were both familiar with these things.

When I was a kid Aja was the record they used to demonstrate hi-fi systems!

Right! Probably a lot of the panning on our records was influenced by stereo test records.

The Van Gelder stuff on Blue Note is mostly mono though, right?

Yes, those are mono, but the balance and the image and the timbre were so perfect. Basically very straight ahead, no EQ.

Aren’t his engineering methods still largely mysterious?

Yeah, he was very secretive. I know people who have recorded at his studio said he used to wear gloves [laughs] and he was generally just very secretive about his technique.

The Steely Dan records are super dry.

I think that was probably also the influence of early rock ’n’ roll too. Chuck Berry records were like that, didn’t really have too much reverb of any kind on them. And Bob Dylan records like Highway 61, there’s basically no reverb. We liked the way his voice sounded against the band. Way up front, but everything was dry, and you could also hear every instrument. Everything was obvious, there was nothing hidden. The only thing that had reverb on it was the organ.

Why the aversion to reverb?

I just don’t want to be alienated from my labor. It’s the same reason I don’t like to play digital keyboards. When you hit the key it doesn’t sound exactly when you hit it, and when you take your hand off it’s not exactly where you take your hand off. That’s very disturbing to me.

I was not expecting a Marxist answer!

[Laughs] Well I like things that are clear, and I don’t like things that are muddy.

That whole world of New York studios, like The Church on 30th Street, where everything from Kind of Blue, to Glenn Gould’s 1955 Goldberg Variations, to parts of Bringing It All Back Home, to the cast recording of West Side Story, all that stuff was made there.

These rooms were amazing. There was an art to designing sound stages in those days, where you just walk in and, just the way you spoke, it sounded so great. The way it was coming back to you. It wasn’t necessarily a lot of reverb …

What was it?

It was the wood they used, the shape of the room. And they were huge. Your voice had a kind of resonance, just talking in those rooms made you feel good.

You guys were familiar with both NYC and LA studios. With a record like The Royal Scam (1976), to take one example, the basic tracks were cut at A&R on 57th and then overdubbed and mixed out in LA at ABC, so there was this kind of bicoastal recording pattern happening.

Well, we were living out there then but we’d go to New York so we could use the musicians. And we knew this engineer Elliot Scheiner from doing sessions in New York. So we called Elliot and we booked the kind of musicians we felt could give us the kind of vitality that we were looking for.

The vibe of the LA music scene must have been very different compared to New York. Even just the players in LA must have been a different feel entirely.

It was different. LA musicians didn’t play as hard, and there was maybe something secondhand about it, in that they were playing R&B, but it was mostly white guys trying to play like Black guys. In New York you had actual Black guys [laughs].

In the ’70s there’s this LA sound, which is this totally glazed, compressed thing …I’m thinking of like the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, Warren Zevon …

Well, they all more or less used the same musicians and the same studios …

And you guys never intersected with that scene?

We had the same manager as the Eagles, Irving Azoff. And some of those guys would come in to do harmony parts. Tim Schmidt used to do some high parts. And once or twice Don Henley came in to do some parts.

I love that story in the liner notes to the reissue of Katy Lied (1975), where Jay Lasker gives you guys a vacant office at ABC to work on new songs.

Yeah, he was the president of ABC-Dunhill. We started as staff writers there. It was one of the last record companies to employ staff songwriters to come up with cheesy songs for people on the label. And we really tried to do that but we were very bad at it. [Laughter]

And out of these failed attempts at writing AM fluff came Can’t Buy a Thrill?

Uh, well, yeah, some of those songs, and some songs from out of our Freaky Book, which was our main stuff.

What’s the Freaky Book?

That’s the first compilation of stuff Walter and I started writing. We wanted to get a band together to play this material that wasn’t the staff writing we were doing at ABC. It was the stuff we were writing that had more adventurous harmony in it. Pieces of things from that time got recycled for later material too. “West of Hollywood” [from Two Against Nature], the core of that was something we wrote in college.

Where was The Nightfly recorded?

We did some tracking in LA, but most of it was done at this place called Soundworks, which was right next to Studio 54. In fact, there was a walkway under the street so that you could get there underground, and a couple times when Studio 54 needed to record something they’d run cables over to Soundworks [laughs].

There’s a lot of great use of synths and sequencers on The Nightfly. You were never averse to those sorts of synthetic textures, even with your closeness to the world of jazz, which often has these very restrictive and reactionary pieties about synths and drum machines?

Well, I remember, when it came out, I got this little ARP Odyssey in the ’70s, and later I got a Prophet. I always played those myself, but it just got harder and harder to keep them in tune. And we really got into sequencing drum parts very specifically when Roger built the Wendel machine, which was probably the first full frequency drum sequencer. We plugged it right into the 3M, the two machines were sampled at the same rate. And I got very good at that kind of sequencing …

You enjoyed drum programming?

Sequencing drum tracks up to like a millisecond, yeah. I used to really enjoy that, but it quickly outwore its welcome. Now I don’t think I’d ever do it again.

There’s just stuff a live drummer does that a machine could never do …

It’s very complex. There’s ebb and flow, this kind of excitement you get. There’s almost a curve to the track, from beginning to end. It would just take too long to imitate that with a machine.

The words to something like “The Goodbye Look” seem to have an espionage atmosphere.

Well, yeah, there was maybe a bit of Graham Greene in that one … There had never been a Steely Dan album that had some central concept, whereas Nightfly was planned as a conceptual piece. In fact, we just did some recording over the summer from the Beacon, and I was thinking of taking a listen to the Nightfly stuff and seeing what we’ve got and maybe putting out some new live stuff.

Part of what I love about your music is how rich and layered and allusive it is. It’s surprising, imaginative, full of ideas, playful. In some ways it has more in common with a much earlier era of songwriting—Gershwin, Billy Strayhorn, Porter, Hoagy Carmichael—where you’ve got unexpected chord voicings, key changes, intricate arrangements, wordplay …

You mean it has content [laughs].

It’s actual composition!

Composition, yeah. But these very principles of composition that you seem to appreciate have of late been seen as a disadvantage.

Who cares!

Well, I don’t! I’m just describing what I’m faced with! [laughs]

You made some of your more recent records at Sear Sound in New York.

Yes. Mr. Sear passed away some years ago, but his wife, Roberta, still runs the studio. She’s an interesting story in herself. Roberta used to direct horror exploitation films and porn, and Mr. Sear did the music for some of those. Really nasty, low-budget films. I remember there were posters of them all around the studio. And Mr. Sear also used to play the tuba in the Radio City Orchestra. He was a funny guy, and an audio genius.

A lot of your songs have these wonderful little details, like “Meet if You Will, Dr. Warren Kruger” (from “West of Hollywood” Two Against Nature 1999), you know, like, where did this guy come from!

Warren Kruger! [Laughs] Yeah. The thing is those little details are I think what make writing good. I remember Nabokov in his study of Gogol notes how a single detail can clarify a whole scene. Or something like in a Kafka story where some out of the way thing is mentioned.

In “The Metamorphosis” Gregor has a picture on the wall of his bedroom of a woman with a fur muff around her arm, which he’s torn out of a magazine and framed …

Exactly, exactly. That just puts you there, in that room.

Your songs have tons of moments like this …

See, there’s something about the name Warren Kruger also, where it has a little bit of Nazification about it I think. So we wanted this kind of ominous effect.

And he’s in Hollywood somewhere!

[Laughs] Yeah.

How about, “Local boys will spend a quarter just to shine the silver bowl.” What is that?

Well, that song is about a cocaine dealer. In the ’70s there used to be a bowl of cocaine on everyone’s table.

Ah! And all these years I thought it was local kids who would pay a small fee to polish the trophy won by the basketball player from the first verse.

[Laughs] That’s good. See, one of the great things about these minimal narratives is that it gives people a certain amount of breadth to make their own associations, and yet it’s still very concrete. We never worked in symbols, it was always pretty straight ahead.

And from the same tune, I’m fascinated by this guy Jack “stalking the dread moray eel” from the deck of his technified yacht. I mean, that’s like Gravity’s Rainbow level weirdness.

I think that was, you know, the people who patronized this coke dealer, they’ve got to have some money, so we were thinking like, OK, a basketball player, and then I guess what would now be the equivalent of something like software king, on a yacht, you know, with special technology.

[Laughter]

But what about the eel!

Well, that’s one of those details. And you said Pynchon, Walter was a huge Pynchon fan.

Is it true that you applied to be a keyboard player in Bob Dylan’s band at one point?

Well, out of nowhere I wrote a letter at one point to Albert Grossman, this is when we were just writing songs in Brooklyn, and nothing was happening. So at one point I just wrote a letter to Albert saying I was available. [Laughs] He never wrote me back. Actually, I got a call in the ’70s from a guy called Rob …. [pauses]

Stoner?

Stoner, yeah.

He was in the Rolling Thunder band.

Right. He asked me if I wanted to come out because there was going to be another leg of this tour, and I was really excited. But it never happened. I thought, oh this will be great, I had a few months with nothing to do but..

And then Can’t Buy a Thrill, a direct lift from Highway 61 …

Right. The thing is, Bob is a culture. And I don’t think we have anything to do with that. I actually wrote an article, a year ago or something … you know the critic who wrote The Anxiety of Influence?

Yeah, Harold Bloom.

Right. Well, I had this article called “The Anxiety of Zimfluence”

[laughter]

And it was about the debt that the people who came after him had to his style.

Yeah, you can’t escape Bob.

You can’t escape Bob. But I couldn’t get anyone interested in it. I’ll send it to you.

Do you think that since he was given the Nobel Prize in literature that kind of raises the bigger question of whether American poetry is now essentially songwriting? Or do we just have a more capacious idea of what “literature” is?

I don’t know enough about modern poetry to give you an answer, but I do think popular music fulfills a lot of the function of poetry. And yeah, Bob’s the one who broke it open. There are other people. [Bertolt] Brecht, who used popular music for his own purposes.

It’s funny how a Kurt Weill tune like “Speak Low” could become an American standard.

Yeah it did, although a lot of his earlier stuff was much more programmatic, written for these plays. Both Walter and I were interested in that. There was a famous revival of Threepenny Opera in the Village, neither of us saw it but everyone was aware of it. Everything from Bobby Darin [recording of “Mack the Knife”], to I think even the Doors covered something …

Yes, “Alabama Song.” So weird this German guy writing about “oh moon of Alabama” …

Yeah, obsessed with America.

I wonder if there even is a counterculture now. Is everything just hopelessly commodified?

Yes. [laughs]

I’ve always thought “Kid Charlemagne” was like this little parable about the fate of psychedelic idealism in the late ’60s …

Yeah, it’s sort of this [Augustus] Owsley story. And I think we’ve just gone deeper and deeper into conservative backlash ever since. It’s still going on, still in place. These old guys in Congress, they never recovered from the anarchy they saw in the ’60s. So the counterculture you have now is commodified, yeah, though it was already commodified within a year or two after it started in the ’60s. I mean by the time of the Woodstock festival I was done with it [laughs].

You called your book Eminent Hipsters, and I take it you’re looking back fondly on what is actually a pre-1960s counterculture, like hearing Monk records on late-night radio and reading the Beats …

Yeah, already a dated idea of people who were outside society. I don’t really know what can happen at this point … I think it was one of the Frankfurt guys who said something like, “there’s hardly a crevice you can get your fingernails into.”

Wow. That high mandarin critique of American culture can get a bit suffocating …

For sure.

And yet things really are pretty ubiquitously corporate now.

They’ve got it down to a science. Take the tastiest stuff out of the margin and immediately cash in on it. It happens within days now.

It’s interesting to consider Steely Dan records along these lines. You guys were doing such strange stuff and yet you were having FM radio hits. How the hell does that work?

Yeah, we never could figure that out. There was a window at that time where FM radio became a big thing starting in the late ’60s, it was really open to creative stuff

There’s an interview with Zappa somewhere where he says something along the lines of, “we were better off with the old guy with the cigar running the label or the radio station, saying, ‘Ah just put it out! See if it sells, who knows’” …

For sure! Back to Jay Lasker at ABC, this guy who you would never think would be interested in anything experimental, and yet he was truly open to new ideas because to him it was whatever sells was great. So you know, throw it against the wall and see if it sticks as a philosophy.

You guys benefited from that.

We certainly did. And I’d have to say it was our producer Gary Katz who connected us with Jay Lasker’s company and he really went to the wall for us.

Is he still in the picture?

I haven’t seen him for a long time. We had a falling out about money. But at the time he was a great booster of our stuff. He talked Jay Lasker into it.

The music industry has changed so much, people don’t really buy CDs anymore and so on. Are you still seeing royalties on your music?

That’s a long story, constantly going on. There are probably thousands of lawyers fighting about that right now, as we speak. But more generally, these days it’s all about streaming, and Pandora …

Has that destroyed the art of the LP?

You can’t divorce the LP from a particular sequence of songs. You know coming after The Beatles and Dylan we just slid into that spot where an album, 40 or so minutes of music, could be a piece of work. I know people still release albums, but I’m not sure if it’s the same. For one thing, kids listen to it on these little pods or play it out of their computer speakers, so there’s no more hi-fidelity, which was part of the thing, part of the experience. It’s like watching films on Netflix, it’s just not the same medium.

Is writing and performing without Walter around a weird experience?

Well, it wasn’t that weird because he was ill for almost a decade before his death and he hadn’t been as active. I was used to trying to keep things afloat. Though the fact that he simply isn’t there is kind of frightening. But in a way he’s always there. He’s in my body, we’ve been together for so long, he’s like my brother, you know.

Does your Jewish upbringing come into play here at all? Do you feel that contributed to the kind of music and literature you were into?

You know T.S. Eliot says it’s not really a good idea to have too many free-thinking Jews around [laughs]. All those guys, Pound, Eliot, Yeats, they all had sort of a fascistic side. They weren’t too happy about the Jews.

But then look at what’s happening in America during those years. Jews are writing the Great American Songbook.

Yeah, exactly. And the Jewish songwriters were intrigued by what was happening in African American music and so on. The whole subculture that grew out of that is really where Walter and I were coming from. Although he was of German ancestry, Walter lived in Forest Hills, he was kind of an honorary Jew, he knew the four questions and all that stuff, had to go to his friends’ Seders. We were both alienated out in the suburbs and this is what there was in American life that seemed to have some soul in it. All you had to do is turn on the radio and you could hear jazz and blues and soul music. The whole musical generation of white kids in the ’60s was really based on their love of Black music. And it worked both ways because of a lot of the tunes were by Jewish songwriters, yeah. We really liked guys like Jerry Ragovoy and Bert Berns, who co-wrote “Twist and Shout,” and Jerry Lieber. You know, these guys grew up in Black neighborhoods, and that’s part of how it happened. They heard something in this beat music that was very exciting.

And this was not concert hall music, it was coming from the street.

Yeah, that’s right. And in way the same thing goes for Jews and baseball.

Say a bit more about that, what do you mean?

It’s the same thing! The players were guys who used their bodies to make a living, which was very different from most Jewish guys at the time, and also, you know, what could be more American than playing baseball. It was a way of integrating into society. If you couldn’t play you could be a fan. But if you were lucky enough to have a little talent and be able to play you could get in on it and you end up as Sandy Koufax. [laughs] It was the only sport I was any good at.

What position did you play?

I played third base, and ended up in right field. Where you’d expect.

Paul Grimstad is a writer and musician based in New York. He teaches in the Humanities program at Yale.