My Counterfeit Israeli Family

A new book by the multimedia artist Andi Arnovitz is an astonishingly original work of Duchampian Zionism

Every so often someone produces a work of art based on a combination of inspirations so unlikely that the piece, itself, feels astonishingly original. My Counterfeit Israeli Family, a book by the American Israeli printmaker and multimedia artist Andi Arnovitz, is in that league; I’d categorize it as “Duchampian Zionism.”

It’s Duchampian in that it incorporates two, anonymous, midcentury family photo albums the artist found in a Jerusalem trash bin; and Zionist, in that Arnovitz, an American transplant who’s been living in Israel for the past 23 years, took advantage of the photographic trove to create an alternate persona: an imaginary sabra, in love with the land; a child of the founding generation that fully participated in the hard work and bloody conflicts that birthed the Jewish state.

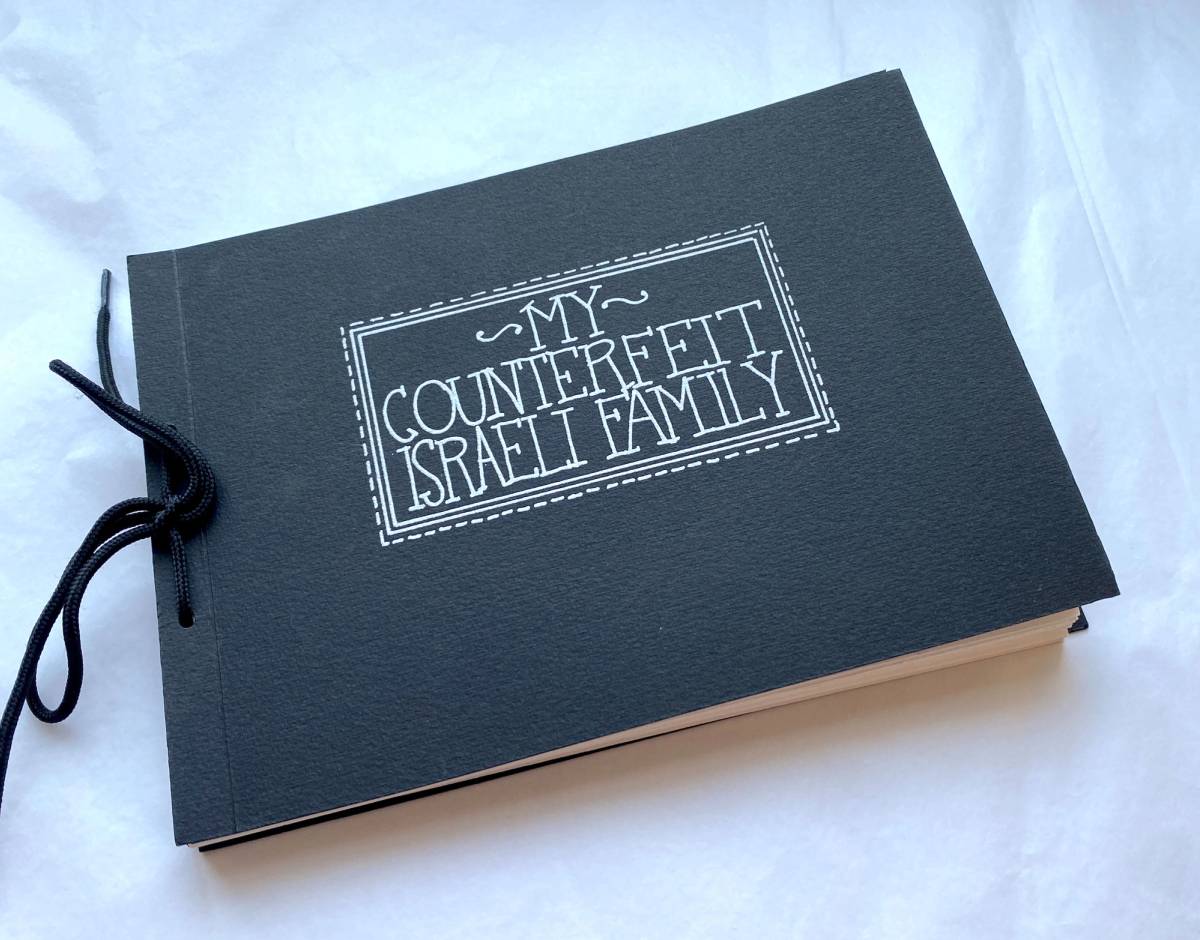

Arnovitz concretized her artwork by constructing a quotidian photo album— with leaves of creamy white card stock, loosely bound between black covers with shoelaces—and populated it with 20 facsimiles of photographs from the abandoned volumes. She painstakingly made copies of the photographs, even recreating the deckle edges of a Brownie camera snapshot, and pasted them in the album framed by hand-colored prints and “diary” entries that limned the life of what she “always wanted to be”: “a sabra born in Eretz Israel—with grandparents who came from Poland in 1914, and a father and uncles who all fought in 1948. I wanted a mother who was part of the founding kibbutz movement. I wanted to be a ‘real’ Israeli.”

In the sweet and fantastical telling—all conveyed through her fictional descriptions of the found family pictures: Her “mom” served in the Gadna Youth Brigade, and her “dad” “worked the land, and fought in the War for Independence. Later, her “mom” became a researcher at Hebrew University. Letting the grainy photographs stoke her imagination, Arnovitz conjures dreamy trips to “the beach in Atlit,” and an Aunt Sima and Uncle Ran with a beautiful apartment in Tel Aviv where, “if I stood on my toes, I could see the ocean.” (The artist grew up in Kansas City, Missouri). Arnovitz even injects some mystery into My Counterfeit Israeli Family, when Uncle Ran and Aunt Sima are replaced, without explanation, a few pages later, by “Uncle Sid and Aunt Sima.”

Until a dozen years ago, Arnovitz did the bulk of her work at the Jerusalem Print Workshop, Israel’s best-known graphic arts studio, and focused most of her energy on printmaking. But then, in what she described, in a Tablet interview in 2010, as a “watershed moment,” Arnovitz encountered the work of sculptor, printmaker, and collagist Kiki Smith, and “everything was different.” Faced with the breadth of Smith’s work, Arnovitz felt liberated. “I decided that wherever my ideas take me, I should follow them,” Arnovitz proceeded along the path blazed by artists like Smith, Louise Bourgeois, and Judy Chicago, as she explored the intersections of feminism and Judaism—and how they are made manifest in the life of an American-born woman living in Jerusalem. Arnovitz began embracing embroidery, needlepoint, decoupage, batik and other methods traditionally classified under the rubric of “women’s arts” in a self-conscious effort to situate her work along the fault line between craft and fine art.

In the exhibition Tear/Repair, from 2010, a series of paper coats based on Jewish women who have changed the world, Arnovitz’s revised artistic vision was on full display. The coats, Arnovitz said, grew out of her perception that “there is no single ethnic garment that loudly and clearly says ‘Jewish woman.’” In her proposed remedies, which often look simple and shapeless, the message is contained in the materials used.

One series of coats is devoted to agunot, the so-called “chained women,” who, according to Jewish law, cannot remarry due to their husbands’ refusal to grant a divorce, or inconclusive evidence of a husband’s death. Arnovitz obtained and photocopied hundreds of ketubot (marriage contracts), and tore them into small pieces. With thread, she affixed the fragments onto massive paper coats. The sleeves, hems, and collars were sewn shut, and the threads, evidence of her painstaking process, were left hanging, a metaphor for the agunah, herself.

“For centuries,” Arnovitz said, “women had few means of creative expression; so many of them poured their talents into the creation of these objects; I attempt to honor these women through my work.”

Recently, she has participated in shows in Poland, Italy, Germany, New York, and throughout Israel, including Jerusalem’s Islamic Museum, the Jerusalem Biennale, and the Anu Museum in Tel Aviv.

Arnovitz, who self-describes as an artist/printmaker, is a former advertising agency art director, who emigrated to Israel with her husband and five young children from Atlanta in 1999, “for a two-year sabbatical,” after the sale of her husband’s software business. As she puts it: “we fell in love with Israel, and never left.”

She artfully and movingly harnesses that love in My Counterfeit Israeli Family. It could have been twee, but all credit goes to the artist for making this X-ray of the powerful tropes of love of family and the Jewish state, substantive, powerful, and ultimately, deeply moving.

My Counterfeit Israeli Family was published in 2022, in an edition of 10, with three artist’s proofs at Jerusalem Fine Art Prints, and is distributed by Magasin III in Tel Aviv-Yafo.

Morton Landowne is the executive director of Nextbook Inc.