The Painting Behind the Door

A stolen de Kooning was found in the New Mexico home of a pair of Jewish retirees. It wasn’t their only secret.

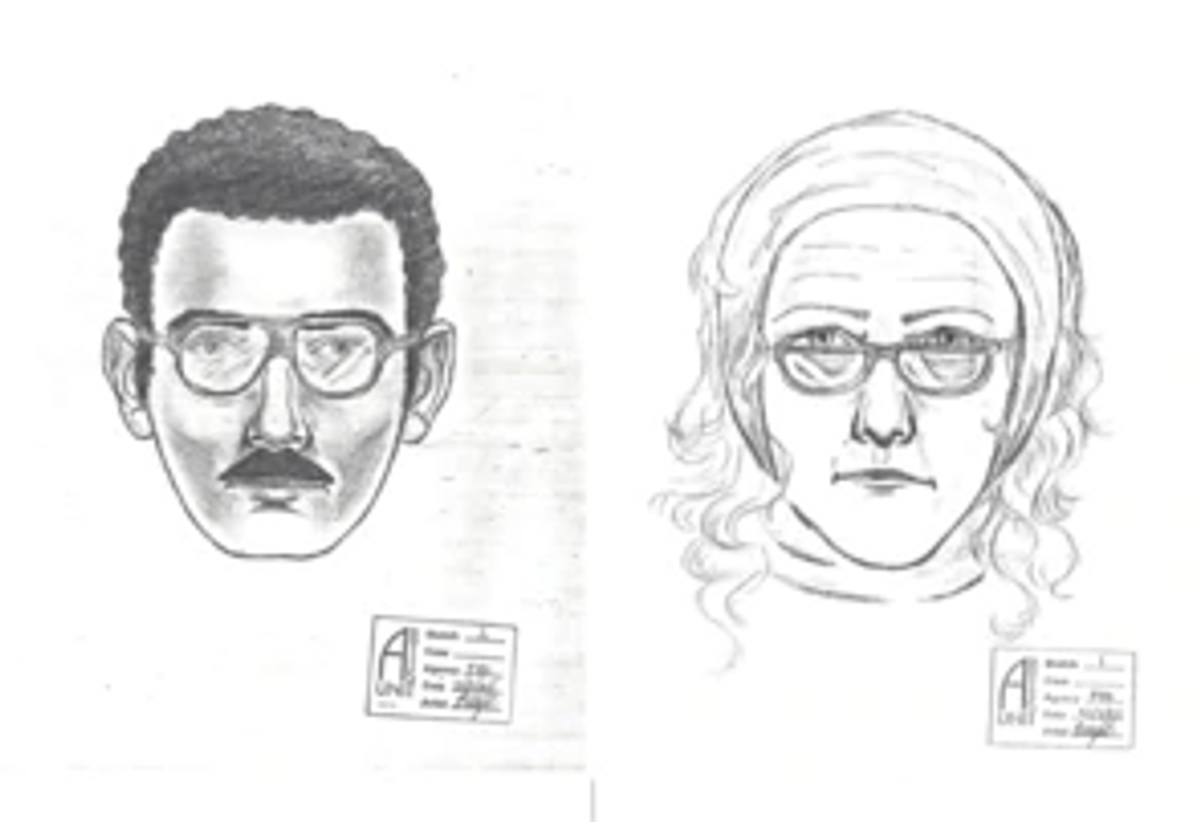

The day after Thanksgiving in 1985, just before opening time, a mustachioed man and a woman with a kerchief over her hair, both wearing glasses, slipped into the University of Arizona Museum of Art behind an entering employee. Though it was a temperate day in Tucson, both wore overcoats. While the woman distracted the guard on the stairwell with questions about a painting, the man proceeded up one flight. A few minutes later he dashed down the stairs, and the couple left in such haste that the guard became suspicious. Upon entering the second-floor gallery, he was horrified to discover that Willem de Kooning’s “Woman-Ochre” had been cut from its frame. Before museum workers could stop them, the pair sped off in what was described as a rust-colored hatchback with black louvers over the rear window. The FBI was called in. A police artist sketched the suspects. Rumors abounded and tips were received, but the heist remained unsolved.

A break in the 31-year-old mystery came in August 2017, but not as the result of any inspired detective work. “Woman-Ochre” was discovered (accidentally would be an understatement) in the remote hamlet of Cliff, New Mexico, population 293, by junk store owners hired to clean out a house following the death there of New Jersey-born Rita Alter, 81. Her husband, Jerry, a former New York City music teacher and pickup jazzman in Brooklyn and the Catskills, had passed away in 2012, also at age 81. Hanging behind the door of their master bedroom, in such a way as to conceal it completely to strangers, was the de Kooning painting. Estimates suggest it could be worth more than $160 million today.

At the moment the painting and the junk man, Dave Van Auker, 55, made their acquaintance, Van Auker had no idea what he was looking at. In fact, he nearly missed it completely, which was, of course, the abiding fear of concerned museum officials—that the masterpiece would just disappear, maybe even wind up at the dump. Says Frances Vasquez, who worked with Rita Alter, a speech teacher in the Silver Schools, “It’s uncanny that it was found, not thrown out; that it was seen. Uncanny in Silver.”

Van Auker and his business partners, Buck Burns and Rick Johnson, had been asked to clear out the pink stucco house on the flat New Mexico plateau by Rita Alter’s nephew, Ron Roseman, who was helping to settle the estate. On Wednesday, Aug. 2, 2017, the three men entered the house and began photographing and evaluating the contents for the purpose of preparing an estimate. They noticed that most of the kitchen items had already been cleared out, and wall hangings and pictures—probably family photos, judging from the placement—had also been removed.

Van Auker entered the master bedroom and, seeing that a panel from the midcentury bureau had broken off and was lying on the rug, was obliged to pull the bedroom door toward him to reach it. He was surprised to see, behind the door, a large abstract painting of a female figure: sexual, provocative, wild. He was drawn to the colors immediately—ochre, black, burnt sienna, and turquoise. He at first thought it was a print, but when he stood up, light from the front window hit the canvas, and he saw its surface was wavy and cracked. It was a painting, and it had been damaged. He also saw that the bedroom door, if opened all the way, completely concealed it. And there was evidence that the painting was valued—a homemade doorstop, a single bolt attached to the baseboard—protected the painting from being bumped.

“It was odd how it had been hung in such a way that it was concealed from sight,” Van Auker recalled. “But there were other things hung in odd ways in the house too—so many paintings crammed in the rear hallway and in the bathroom, so I didn’t think much of it.”

The men finished their work assessing the contents. They called the nephew, Ron Roseman, to give him their offer: $2,000 for all the contents. They liked the midcentury furniture, and there were a few paintings, lamps, and objets of interest, but nothing that seemed out of the ordinary. Roseman accepted. One room contained shelves piled with slides and home movies, travel notebooks, and a map with pins pointing out all the countries Jerry and Rita had visited, a collection Roseman had already told them would be packed up by a neighbor and sent to him.

The next day, Thursday, Aug. 3, Van Auker and Johnson returned to the house to collect some outdoor pottery. Van Auker, who had trained as an interior designer, lifted the de Kooning painting from the bedroom wall and, after he and Johnson had loaded up their truck with the pottery and some smaller household finds, slid it into the back. They headed southeast away from Cliff to their shop, Manzanita Ridge Furniture and Antiques, in nearby Silver City, about 30 minutes away.

They descended through the juniper-dotted scrubland, hugging the banks of the winding Gila River for a stretch, then proceeded down into the valley on which Silver City had been built in the 1870s atop an Apache Indian camp. Fever for the gold and silver found in the nearby hills was so high at the time that one Las Cruces newspaper reported after the discovery of a rich new silver strike, “but a few hours elapsed before the hill was like a swarm of ants.” The Apaches had no hope against the number and fervor of white prospectors, whom they had come to call the “goddamnies.” Running battles between the white men and the Apaches continued until the surrender of Geronimo in 1886.

Once Van Auker arrived at the store, he set the painting down in the airy storefront on Bullard Street, and he and Johnson proceeded to carry in their new goods, clean them, and prepare them for sale. But almost immediately James Cuetara, a local painter, wandered in, knelt by the painting and looked it over. He of course saw the signature—de Kooning—and he announced that he thought it might be the real thing.

Manzanita Ridge being an informal gathering place for the ragtag group of artists, writers, and daydreamers reanimating (and redecorating) the old mining town, it didn’t take long for word to get out. Cuetara returned a while later announcing that de Kooning paintings had been sold for millions of dollars. That got everyone rattled. A few more locals weighed in. When Cuetara came back for his third visit and offered to buy the painting for $200,000, Van Auker decided he’d better pay him some mind.

He turned on his computer, scrolled through dozens of stories about art thefts, and clicked on one from the Arizona Republic. The story was titled “Unsolved Arizona mystery: de Kooning painting valued at $100 million missing for 30 years.” It had been written a year earlier as part of a last-ditch effort by the University of Arizona Museum of Art to revive the cold case on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of “Woman-Ochre’s” theft. A photo of the painting popped onto the screen.

“Is that our painting?” he wondered. He read on and learned about the 1985 robbery. Then he buckled down and seriously compared the painting in the story with the one in front of him, mounted now in a cheap gold frame. They were very similar, and he knew what he had to do. Within five minutes of seeing the story, he picked up the phone and called the University of Arizona Museum of Art. He told a student receptionist. “I think I have your stolen painting.”

“Hold, please,” she said.

‘Woman-Ochre’ was kidnapped from her home and she was shackled in this ugly frame for 31 years. She was degraded, and now she’s free. I know it’s an object. I know that. But that’s what I truly felt. She was alive to me.

Van Auker was connected to Olivia Miller, the museum’s curator of exhibitions. They spoke briefly and then Miller rang off. Van Auker later told a local reporter, “Olivia was very calm and I was thinking to myself, ‘This woman is going to think I’m a nut job, that I picked up a print at the Salvation Army and think it’s a de Kooning.’”

But she didn’t. Instead, she texted him back, asking for the painting’s dimensions. The size of the painting Van Auker had measured was 40” x 30” (102 cm × 76 cm), slightly off from the original, but consistent with the canvas having been cut from its frame. She asked him to send photographs of the front and the back. And then she stopped communicating.

“We waited for a return call for hours that afternoon,” recalls Van Auker, who shares a passing resemblance in voice and manner with the television character Cam Tucker from Modern Family. But they heard nothing. He and Rick and Buck didn’t know what to do—with the painting or with themselves. They knew word was traveling quickly through town, so they wrapped the painting in a blanket and stashed it in the bathroom, the only room in the store that could be locked. When closing time approached, they were afraid to leave the painting behind. Too many people knew it was there. At that point, even the no-nonsense Johnson was getting worried.

“Someone could just break the window and come in here and steal it,” said Van Auker. “The alarm would go off, but by then it would be too late.” They decided to drive the painting home with them. Van Auker and Buck Burns, who are life partners, live together in Pinos Altos, a woodsy area north of Silver City, where in 1860, the first local gold strike had been made. Rick Johnson lives nearby.

“Here we are with a painting that might be worth hundreds of millions of dollars and no one is calling us back!” Van Auker recalled. “It was already 10:00 at night! Everyone in town knows where we live. Anyone could show up at our door—any cranked-up meth head—I mean, people have killed for far less!”

The memory that remains with Van Auker is replete with both terror and self-mockery. He remained awake all night on the living room sofa, a Colt .38 in his lap, a cheap Chinese Norinco 9mm handgun on the coffee table in front of him, and a .22 Smith & Wesson under a towel on the entry table. The painting was behind the sofa. The fact was not lost on Van Auker that he had only once before shot at a moving target—a rabid fox—which he had missed.

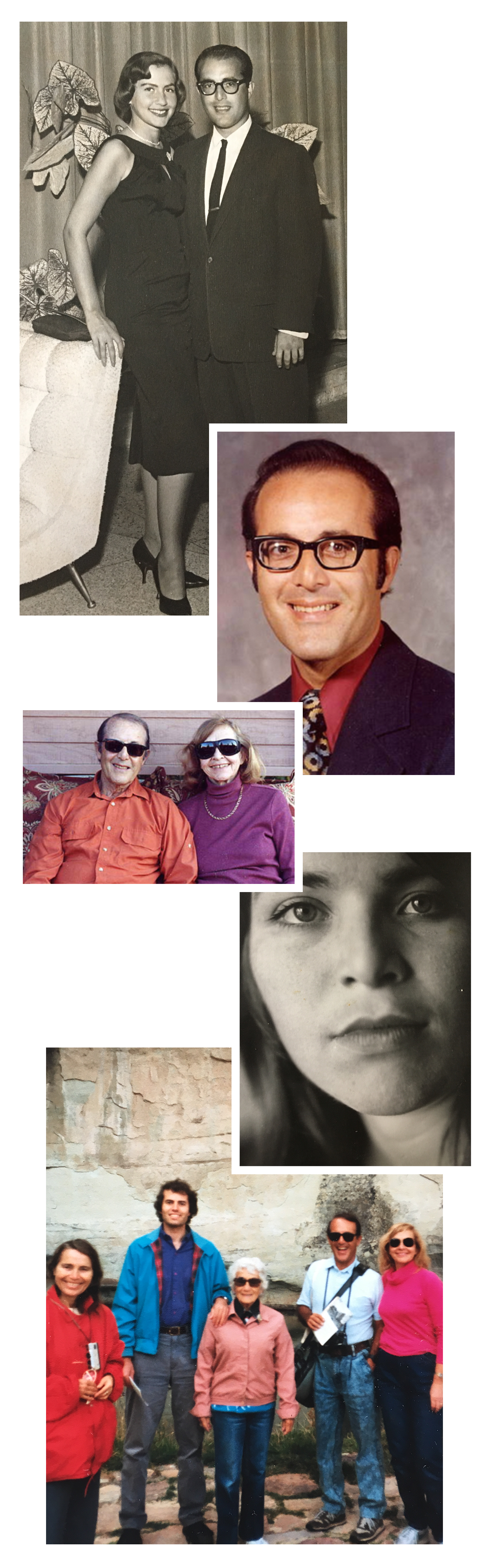

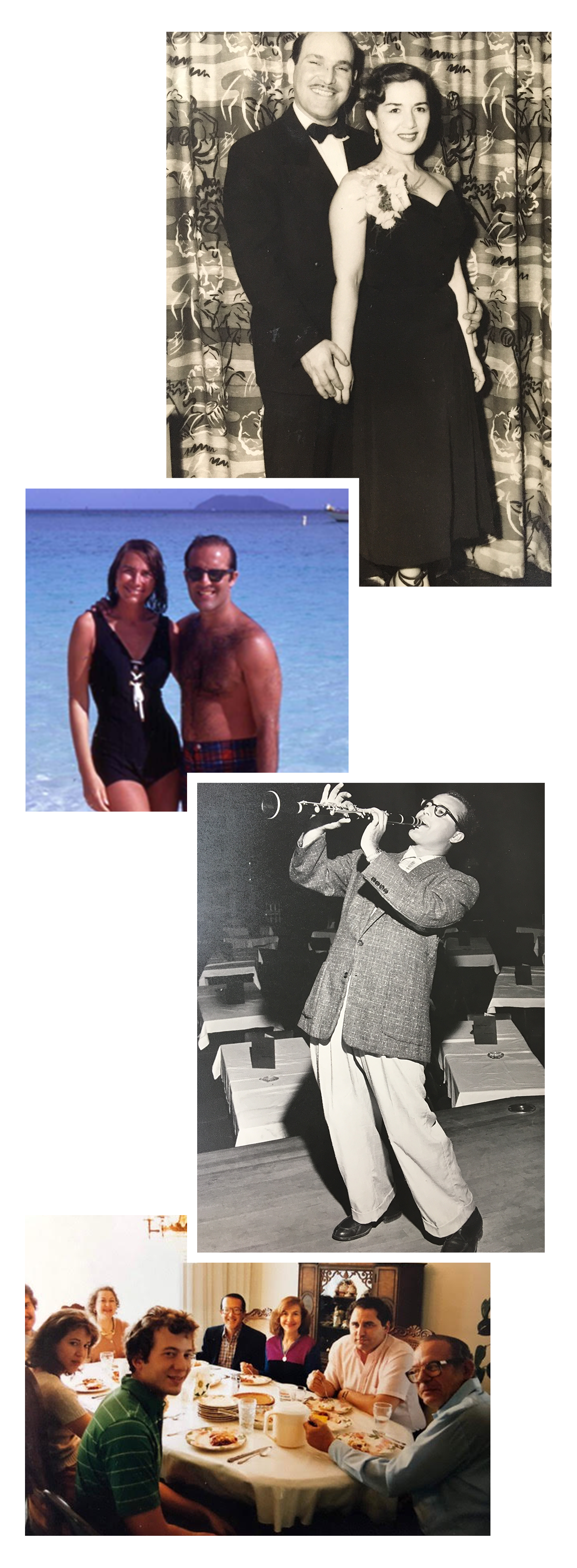

The main suspects in the theft of “Woman-Ochre” are Jerry and Rita Alter, who moved to the area from Closter, New Jersey, in 1977, set up a trailer, and built themselves a home with swimming pool and elaborate gardens. Rita was a dedicated and well-liked speech therapist in the Cliff and Silver City public schools, and Jerry had been a saxophone and clarinet player at resorts, hotels, and parties in New York City and the Catskills and a music teacher at an elementary school in Washington Heights before moving west. He told his new neighbors that he was retired, though he was only 47 when he moved to the area, and 43 when he had bought the property. The couple kept largely to themselves in Cliff, but they loved to travel and took repeated trips around the world. Jerry boasted that they had visited over 140 countries “on all continents” and the two polar regions.

But how had they pulled off such an outrageous act, if indeed they were the thieves? And more curiously, why would the couple, whom neighbors remembered as cultured and well-educated, risk jail time and the humiliation of getting caught to steal an immensely valuable painting from a public art museum?

Was there some personal history that needed settling? Had Rita known de Kooning, or even possibly been the model for the painting? Did she or Jerry feel somehow the work belonged rightfully to them? Was the painting stolen as a love offering to Rita? The house was filled with paintings, one of which looked like a clumsy imitation of a de Kooning. Another appeared to be painted in the style of Matisse, one of de Kooning’s key influences. On the back of the Matisse study is written, “Alter, 133 West 14th St, NYC, NY”—an address not far from de Kooning’s famous Tenth Street abode. It is dated March 1955, the beginning of the period in which de Kooning rose to fame.

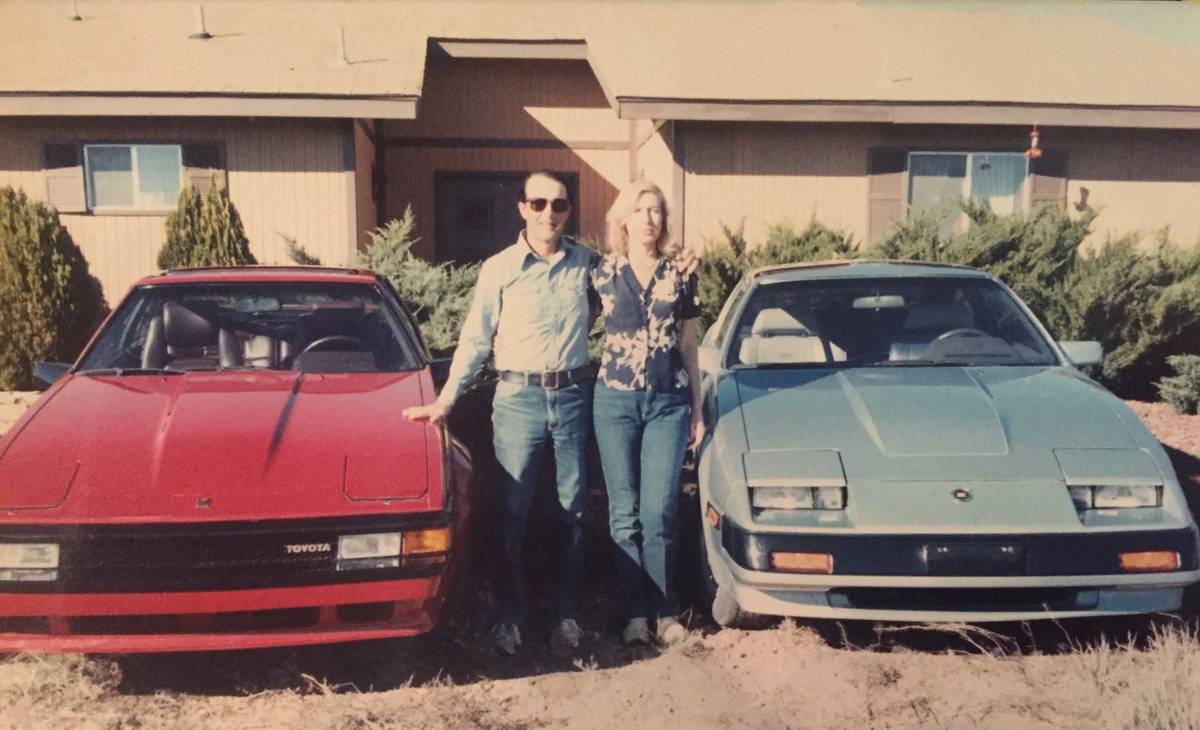

Moreover, the sketches of the suspects look very much like photos of the couple, and the getaway car resembled the red Toyota Supra that Rita drove in those days, according to Dido Gutierrez, the local mechanic who worked on it. Rumors abounded in tiny Cliff and the larger Silver City nearby, particularly after stunned residents discovered that the reclusive Jerry had self-published two books of poetry and a collection of short stories a year before he died. The stories include tales of art heists, some successful, some not, including one that had similarities to the de Kooning theft. They include tales of murder, violent sexual attacks, international jewel thefts, and many stories of violent revenge. Neighbors in Silver City, a former hideout of outlaw Billy the Kid, another New York transplant, have analyzed the volumes and discussed their theories over coffee at local haunts. What clues, evasions, or confessions did Jerry leave behind? Was he more than a music teacher? Was he a grifter, or a professional art thief? And how to explain an estate of almost $2 million in cash that the Alters—two public school teachers, one of whom retired in his 40s—left behind?

The crime remains even more curious because the FBI case, initiated in 1985, has never officially been closed. Dave Van Auker, who has remained cued into every twist and turn of the investigation, says, “Back in October 2018, Stacey [Gutierrez, the lead FBI special agent on the case] said ‘we’re done. The case is closed—we’ve done everything and we’re not investigating anymore and we’ll be announcing our findings in 30 days.’ And then the 30 days came and went, and then 45 days came and went.” Van Auker adds: “I think they’ve found something else.”

Twenty-four hours after Van Auker’s call to the University of Arizona Museum of Art, curator Olivia Miller and six museum colleagues, along with the Grant County, New Mexico, sheriff and a few of his officers, arrived in a convoy to Silver City. By that time, evening on Friday, Aug. 4, the painting had been placed for safe-keeping in the office of a lawyer. Miller walked into the room and knelt before the picture, which was leaning against the wall. She had never seen the work in real life before, and she studied it, flushed and disbelieving. She admitted to having had idle daydreams that the painting would one day be found, or that someone would quietly mail it to the museum. But here it was, before her very eyes, though battered, brutalized, and torn. The room was silent. Finally, overcome by emotion, what she managed to say was “holy shit balls.”

Everyone but the museum staff and the owners of Manzanita Ridge was shooed out of the room, and the original frame, from which the canvas had been cut in 1985, was brought in. “We thought we’d be able to compare the fragments,” recalled Miller, “but it was not an ideal viewing space and we made the decision not to remove the painting from the current frame so as not to further damage it.” Whoever had restretched the canvas had done so with multiple staples, haphazardly placed, and had then stuck the frame to the stretcher with eight to 10 “honking large screws”—Van Auker’s phrase—making even more holes in the formerly visible parts of the canvas.

“Woman-Ochre” was taken to the Grant County Sheriff to be crated for travel, and was stored overnight in a vault. On Monday, Aug. 7, it was transported via armed convoy to Tucson. New Mexico state police escorted the painting to the state line, Arizona’s state police took it the rest of the way.

Van Auker said there never was a question in his mind nor the minds of his partners that they would return the painting promptly to the museum, though at least one acquaintance suggested he hold it for ransom or worse. “What it felt like to me was that ‘Woman-Ochre’ was kidnapped from her home and she was shackled in this ugly frame for 31 years,” he told the University of Arizona News. “She was degraded, and now she’s free. I know it’s an object. I know that. But that’s what I truly felt. She was alive to me.”

Olivia Miller later apologized to Van Auker for the many hours of silence between his original call to her and her team’s arrival in Silver City the next day, explaining that after the museum deduced the painting was likely the missing de Kooning, she was prohibited from speaking to him further—for fear that a confirmation might spur him to abscond with it. But, says Van Auker, recalling the fear and panic he experienced the night he and Buck held “Woman-Ochre” at their house, the strategy of silence “could have backfired. It could have caused us to run—or toss it” to relieve their mounting anxiety. Later, the three men were hailed as heroes. They refused the reward that had been offered by the museum.

Over the next few days, world-renowned conservator professor Nancy Odegaard of Arizona State Museum authenticated the painting as the original work after confirming signs of documented repairs, matching brush strokes on the painting with those on the canvas pieces still attached to the original frame, and testing for a prior varnish finish. The painting was in no shape to be displayed, however. Miller says. “First, the frame itself was horrible. And the stretcher bars were not made of quality wood. It was painful to see all the damage—the staples and screw holes on the edge of the painting, but whoever did it didn’t seem to care.”

Not only had “Woman Ochre’s” canvas been sliced out of its frame, but it had also been yanked from the lining to which it had been attached with wax. This had made additional tears in the canvas that someone tried to repair by adhering some kind of material to the back. The repairer even had the chutzpah to add some white and greenish yellow paint to the lower right leg of the figure. Miller said it looked like the added paint “wasn’t even oil.”

She recalls, “We kept saying, ‘the poor painting, the poor painting.’”

But at least “Woman-Ochre” was home, returned to the museum to which it had been donated by a wealthy builder from Baltimore named Edward Gallagher Jr. in honor of his 13-year-old son, who had died in an accident. It is now at the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles, where it will remain for a year undergoing conservation, research, and repair. The Getty Museum will exhibit it next summer, and then it will return to the UA Museum of Art. “That’s the plan,” says Miller. “Provided there are no big surprises.”

On Sept. 13, 2017, one month after the discovery of the painting, I drove to suburban New Jersey to meet Carole Sklar, 82, Jerry Alter’s only sibling. I figured if anyone could shed light on her brother’s character and relation to “Woman-Ochre,” it might be her. The house where Carole lives stands out from the rest of the other large homes in the neighborhood with its high gambrel roof, built in the Dutch colonial revival style popular in the early 20th century. Waiting for me at the door of the screened-in porch is a tiny woman with a huge, expectant smile. I ask her about the unusual roof shape and she says, “I love this house, the house with the shrug. It’s from 1906. Martin and I bought it on a whim. We never made a mistake.”

She ushers me inside into sunny rooms decorated with weavings and other crafts from South America, where she lived for many years with her husband, Martin Sklar, former principal bass player of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. One downstairs room is lined with photos of Martin and Martin’s father, Philip, who was Arturo Toscanini’s principal bass player in the NBC Symphony Orchestra. Carole says Philip, who was born in Russia, also built basses for Toscanini, a former music director of the Metropolitan Opera, La Scala in Milan, and the New York Philharmonic. A bust of the renowned Italian conductor rests on the credenza. Carole’s voice rises with excitement when she holds up a photo of Martin and herself: “Here’s Martin and me. He gave me life—like Geppetto breathing life into Pinocchio.”

Martin, she tells me, passed away seven years earlier, at age 68, to her utter desolation. “His mother lived to 96. He was supposed to live forever. I am seven years older than he, and I never thought I would outlive him.” They never discussed death, she told me.

“We were never going to die.”

Jerry and Rita believed the same thing, I learn. They exercised relentlessly, ate healthy food, and believed that by sheer force of will they could forestall the inevitable. This was only one of their delusions, I was to discover. In spite of being in possession of a priceless painting that belonged to the public, they had not prepared a will, nor any document designed to identify or protect “Woman-Ochre.”

Carole is a painter herself, and the living room, where we sit, is filled with her work. She says she is represented by a gallery and has sold over 100 paintings. She lets me look around. The work is skillfully done, and she has her own distinctive style. The paintings are haunting, moody, and filled with characters who seem utterly alone even when accompanied by others. This diminutive woman paints figures with elongated bodies and Gumby limbs that are often placed together with other human forms of a much different scale, inviting conversation but locked in the silence of disparate geometries. In one painting, a large purple car with a fancy grille is occupied by two remote-looking adults in the front seat. In the back is a single girl in white, her tiny arms splayed wide against the window in despairing protest.

“That’s me,” she says approvingly. “I’m always the one who is making trouble and causing a fight.”

She has agreed to tell me the family story. As she puts it, “I am the self-proclaimed kind of family archivist.” A natural raconteur, she turns a catchy phrase. She makes it clear up front that Oedipal rivalries in the household were raw. “I wanted my father for myself. He always used to say, ‘if anything happens, Jerry saves Carole, and I save Mommy.’ I hated that. I used to ask him if he had met my mother and me at the same time, who would he have chosen?”

I am startled by Carole’s audacity and—for someone coming of age in the 1950s—her psychological naivete. She now expresses the regret she was unable to acknowledge earlier in her life. “My mother tried so hard to please, to give at home and at work. But she wasn’t respected properly, especially by me. She knew I was collecting impressionist paintings, and she would come home and give me folders filled with them. And I would throw them in the garbage. I wanted to hurt her. I just couldn’t be nice to her. I was openly disrespectful of everyone.” She tells me that Martin helped mend her feelings and reconcile with her family.

She pulls out the family photo albums. There is her mother, Mathilda, posing seductively in a stylish bathing suit, wrapped in the arms of her husband, Seymour, who is dressed in striped T-shirt with high-waisted, baggy trousers, a cigar rakishly in the corner of his mouth. Another shows her brother Jerry as a toddler, brown-haired, soulful, worried. “He wasn’t a happy guy. He was a guy with a sparkle, but he wasn’t an easy-going happy-go-lucky man—or child.” And there were photos of Carole, a winsome girl with blond braids, carrying a doll.

The family seemed to have been firmly ensconced in New York City Jewish life—the parents can be seen at gatherings in banquet halls with white linen tablecloths and men dressed in silk-collared dinner jackets and women in elegant postwar chic. Carole says some of the parties were for the Good Fellowship Lodge of the Knights of Pythias, a benevolent organization of which her father was a member. She recalls her parents’ apartment had hidden in it, behind the piano, weapons that the Knights of Pythias were to ship to Mandate Palestine. The family supported the fledgling state and despised the British for their restrictions on immigration and their harsh treatment of the aborning Jewish state. “We didn’t use British petroleum in the car nor attend British flicks.”

Seymour Bernard Alter is a garrulous-looking man, slightly rotund, always smiling, and clearly head-over-heels in love with his wife, the former Mathilda Wineman, who is beautiful, has a knockout figure, and dresses with great care and taste. She stands out from the other women with her hats, head pieces, long gloves and beaded purses. “She was a cute one,” says Carole. “I mean really cute.”

“The whole family was artistic,” Carole explains. “My mother loved to draw and my father sang and he loved art.” Seymour was a strong, though unschooled, tenor.

Like many other families of Jewish immigrants in the early 20th century, the Alters were nourished by dreams limited only by their vivid imaginations and shaped by the creative energy of a people recently released from hundreds of years of constriction in ghettoes and heders. The rough-and-tumble energy, hopes, and ambitions of these generations changed New York City and the United States. But this particular family got its start at a very unlucky moment. Mathilda and Seymour, aged 19 and 20, were married on Aug. 17,1929—two months before the stock market crash that inaugurated the Great Depression.

Tragically, the year of their nuptials also marked the deaths of Seymour’s mother, father, and an older step-brother. There would be no wedding celebration, just a simple ceremony in the rabbi’s office. As Jerry later wrote in a story: “They were so poor. Each was part of a large family which lived from day to day. But they loved one another in the uncomplicated way only very young people could. With the unbounded enthusiasm of youth, they planned to marry, confident that somehow, they would make their way in the world, just like everyone else in their circle of family and friends. There was plenty of work to be had for an energetic, ambitious young man. …”

Unless, of course, all the jobs evaporated overnight in the single worst economic event in world history. Six months after the marriage, Seymour lost his sales job. Because he had dropped out of school at age 12 to help support his family of 13 children, he had neither schooling nor specialized skills. His circumstances were all the sorrier because when he first left school as a boy, his grammar and composition teacher visited the Alter home to beg the parents to allow Seymour to return, saying he was one of the best students in the class and had the potential to be a lawyer or writer one day. But the boy’s father, already sick himself, and with three young girls at home to feed, said the family needed the additional revenue that Seymour was bringing in. The teacher went so far as to offer to pay them a few dollars a week out of his own meager salary, but the father hardened his stance, insisting the family would not accept charity. Seymour, he said, “made his bed. Now he has to lie in it.”

Seymour got odd jobs, but the newlyweds could no longer afford their own apartment, so they moved in with one of Seymour’s sisters in the Bronx. A son, Herman Jerome, was born on Dec. 16—Beethoven’s birthday, Seymour was wont to point out—in 1930, compelling the family to move again, this time in with Mathilda’s parents, who were no more accommodating. They allowed Mathilda and the baby to stay, but told Seymour he would have to find lodging elsewhere. Mathilda’s mother scolded her daughter for marrying so young and to a man with limited prospects. Seymour was thus forced to move in with an older brother—and apart from his wife and infant son.

But Seymour was energetic and ambitious. Reading the paper one day, he saw a new radio show was looking for tenors. He decided to apply. First, he sang, “My Yiddishe Mama,” which reportedly brought tears to the eyes of the producer auditioning him. He then offered his own rendition of “La Donna É Mobile” from Rigoletto.

A week later, Seymour got the call that only happens in the movies. He was offered a job singing on the radio. “My father was ecstatic,” says Carole. “He was very excited until they told him that the first few months he had to work on probation until they raised money for the show. But my parents needed money, not probation. And my father couldn’t accept the job because he had to do what he had to do.” She slashes the air with her hand in a grim, fatalistic gesture.

This is clearly a story that has great resonance in the family. Both Carole and Jerry embraced the theme of an unfeeling world beating down a good man—Carole expressed this belief in her observations to me, Jerry in his written stories. But in Jerry’s renditions, he took the liberty of rewriting the endings, as if he could magically restore to Seymour his dreams and his dignity. In one, “Sam’s Big Break,” written more than half a century after the event, Jerry corrects the historical record by having the radio producer call “Sam” back months later, saying he was ready “to offer you a generous contract starting immediately.” For her part, Carole admits, in spite of the charmed life she has led, “I never thought the world out there was willing to give me a hand.”

In real life, the audition had given the ever-hopeful Seymour an idea, and for a few days he sang in the courtyards of apartment buildings in the Bronx. Much to his surprise, people threw pennies out the windows for him. The first day he made $6, more than he had made per day for many weeks. But after three days of singing his heart out, he lost his voice. The doctor told him he had nodes on his vocal cords. Singing was out of the question without an operation, and there was no money for that. But soon, he would find a new profession, this time one that stuck. Rather than swinging for gold, he would salvage it.

“He would take trips to the south,” recalls Carole, “or even to Montclair, knocking on doors asking if they had any old gold—which was usually jewelry or evening gowns, which my mother wound up with. But my father would buy things and then sell them in a kind of thrift shop type situation. Or he would sell it to people who would melt down very beautiful precious objects into a lump of gold. But the buyer wanted to pay only the value of the gold and not the value of the beautiful object.”

Eventually, he had a store on Sutton Place: 54th Street and First Avenue. The English actress Hermione Gingold (whose characteristically gruff voice was the result of her own vocal nodes) used to drop by and torture Seymour. She’d leave with armfuls of goods, only to return the next day saying she’d changed her mind. These episodes sent Seymour into peaks of joy—when he thought he’d had a day of good receipts—and vales of disappointment after their return. Nevertheless, the love of art and appreciation of beauty continued to animate the family. “We grew up with things like beautiful furniture and oil lamps and running around the house crashing into antiques,” Carole recalls. Family outings were to parks, museums, science expositions. “All my toys were coloring books paints, paint sets, easels.”

And proud Papa thought his son might be a singer too. “My dad used to lift Jerry onto the table when he was 3 or 4, and he would sing ‘La Donna É Mobile’”—the same song Seymour sang at his audition for the radio show. “The kids were encouraged to blossom,” says Carole. But they may also have felt great pressure to please their father and help lessen the pain of his failures. In a story called “To Cast a Die,” Jerry wrote about a 6-year-old boy asked by a teacher to sing before a class of boisterous students. “Distracted by the totally inattentive class, the boy’s mind went blank …” and he forgot the words to the song, humiliating himself. And then it happened again in another classroom. Later in the story, the boy, who became a trumpet player as an adult, suffers a similar lack of confidence. “Henry felt a panic, as his mouth became dry and his heart raced wildly… he botched the lead repeatedly, to the shock of the leader and the other musicians. Even people on the dance floor stopped dancing and looked up, appalled at the sounds.” Throughout the years, Jerry sent his stories and poems to his sister for comments, criticism, and approval. Attached to this one, sent in 2004, he wrote: “As you can see, parts of ‘To Cast a Die’ are autobiographical.”

When I ask her if she remembers the childhood event to which Jerry refers, she says no, insisting he was a professional, and never had any trouble before an audience. But later she acknowledged that sometimes she only wanted to hear good news and blocked out the rest. “I didn’t know what was going on in other people’s lives. I was interested only in my own.” She shows me photos of Jerry playing the clarinet and saxophone at local events in Brooklyn, where the family had moved from the Bronx in 1937, when Jerry was 7 and Carole was 2. By the 1950s, the album shows large black-and-white professional photos of Jerry playing in bands in the Catskills. And there are what look like promo shots of him with clarinet, saxophone, and flute. Jerry is a sharp dresser, and he certainly looks the part.

“Jerry was a band musician and he went to the Catskills and played in the summers—Grossinger’s and I think it was Flagler’s. Sixteen, 17, 18. When he was 15, he was doing weddings, bar mitzvahs, and dances. And because he earned his own living—I mean, he didn’t have to spend anything for the household—but he saved money so even when my father was sick, Jerry had enough to put some money in their bank account.”

She turns the pages of the album and shows me photos of herself in her late teens. She had steamy good looks, and she knew it. “I wanted to be different. I used Hollywood movies as examples of what I would like to be—or Russian novels—I wanted to be some kind of Natasha you know—someone other than who I am. And what was I? Just a little Jewish girl from Brooklyn. With visions of another world.” She vowed she would never work, and never have children. “Never wanted to have useful skills or be employable. That’s one reason I majored in fine arts. Philosophy would have been a second choice.”

She kept those vows, with the help of a rent-controlled apartment and two marriages to highly successful, creative men. “I wanted beauty and fame,” she said. “I was pretty. And my fame came from the men I married. Whatever I achieved, I got from association with others who were great. With me, it had to happen magically.”

Carole remembers that when she was 12 and Jerry 17, he bought her “a little camel’s-hair coat and a brown hat with ear muffs.” He was “just a kid himself, but he bought me that. So, I think he had a very strong sense of responsibility.” Two years later, when Jerry was 19, and Seymour only 39, Alter pater had a very serious heart attack, which permanently damaged his heart and required a long recuperation at a nursing home.

“You know everyone says it’s so strange they had the painting in their bedroom,” Carol says, changing the subject. “I have to stress this strongly, I have art in bathrooms, I have art in closets. I’m not hiding it. Art in living rooms is not more important than art in the cellar. I don’t consider anything hidden in someone’s house—if you really want to hide, it, dig a hole in the garden and hide it.”

I am surprised by her statement, and her willful misunderstanding, because the attention drawn to the location of the stolen de Kooning had little to do with its presence in the bedroom, but rather, its location exactly behind the bedroom door, for the purpose of its concealment from public view. “Before, I was tending to think Jerry might have bought that painting at an estate sale in Scottsdale or something,” she says. “Now, if it turned out that he and Rita stole it, it strikes me as kind of thrilling. I kind of love it—my brother and his wife as Bonnie and Clyde. ’Cause I’d go out and kill somebody tomorrow to be recognized, wouldn’t you?”

On Jan. 17, 1964, after she had finished up her day’s work as a statistical typist at Seagram’s, Mathilda arrived at the hospital with a new pair of slippers for Seymour, whose doctor had earlier in the day ordered him to check in. Suddenly superstitious, Seymour remarked on their color. “Black?” he asked, raising his arms wide. Seymour looked at his wife with one final expression of disbelief at the luck the world had dealt him, suffered a massive heart attack, and died. He was 54.

The family never got over it. Jerry never got over it. “His was a loss from which there would be no recovery, despite a life which was to be as rich as it was long,” Jerry wrote about an autobiographical character in a story titled “Never Say Die.” “His overriding emotions were anger and sympathy. He felt a profound, undying compassion for his dad, who was ultimately beaten down in a world of heartless people and cold circumstance. For this, he would always harbor deep rancor and antipathy.” Jerry wrote several stories about his father’s life, stories on which he lavished more care than the others. In them all, he played God and refashioned the endings, making the poor man rich, the unlucky man overflowing with good fortune, a dead man come to life in the soul of another. In one, titled “The Art of Living,” he wrote about the efforts of his character “Sam Arons” to paint while recovering from a heart attack. This story line borrows from reality: Seymour did the same, completing about 15 oil paintings on canvas board in 1949 or 1950. In real life, Seymour’s style was “wild shipwrecks at sea in expressionist style—thick impasto—with the pallet knife and all of that,” said Carole. Interestingly, Seymour chose the style of painters of the downtown scene that included a dirt-poor Dutchman named Willem de Kooning.

In Jerry’s story, “Sam” becomes such a success that his work finds its way into “America’s top galleries and museums.” Eventually, “Sam” wins awards, receives honorary doctorates, and makes tens of millions of dollars, $30 million of which he donates to a cardiac research program at the prestigious “Eastern University.” The researchers whose work he supports then go on to develop an artificial heart that saves Sam’s life. In Jerry’s story, a happy, satisfied, and rich Sam dies in his sleep at age 100.

Such dreams! Such glory! In Jerry’s rewrite of Seymour’s life, it’s a straight-line success from hospital bed to first-rate gallery to “Eastern University” honorary degrees, money, and fame; Jerry heaps upon Seymour talent, recognition, wealth, status, and a long life—everything Jerry believed had been unfairly taken. Seymour, even before his untimely death, had been taken from Jerry—he had been forced to live apart from his infant son in the early years of his marriage, and both his children were deprived of the presence of their father because of the long hours he was obliged to work doing the unskilled work that was his fate.

Theft recurs as a family theme, weaving itself into the family’s very fabric. One summer in 1953, Jerry was on staff at a hotel in the Catskills. A young woman named Rita Sinofsky worked at the same place, minding the children. “One of the other members of the band,” recalls Carole, “maybe a trumpet player—because those are wild—asked Rita to go out on a rowboat with him. And Rita was kind of excited about going out with this trumpet player and she walked back to where the band guys were hanging around. I guess they kept the workers separate—they lived in bungalows or something, and she came by and Jerry was on the little porch and Jerry saw Rita and he thought, ‘I want that girl.’”

Jerry did not hesitate. He stepped up to Rita, who was 18, and said, “He’s split. But I’ll go with you.” He saw something he wanted, as his sister put it, and he took it.

In almost a mirror event 18 years later, Carole caught sight of a man, who turned out to be Martin Sklar, and determined he would be her (second) husband, though he had pledged troth to another.

“I rode my prized Italian, aluminum framed, lightweight bike from 54th Street to 59th Street into Central Park and rode the loop,” Carole recalls. “Very few folks were in the park. It was about 9 a.m. Then I carried my bike down the stairs to Bethesda Fountain and sat on the rim. I looked over my shoulder, and coming down from the Boathouse was this man, and I said to myself, he was going to sit down beside me on my left side, and he did.”

She was wearing “green snakeskin boots with light green panty hose, a scoop-necked lavender jersey under my jeans jacket and blue denim miniskirt. I still have the jacket. And we talked and talked—he had just come back from Colombia. And he was married and he had a little baby.

“But the way I saw it, too bad. It was up to him to look after his baby.

“His loss was the true love of his daughter. But the gain was the true love for me. And I would not have traded it for anything in the world.”

In these meetings—both of which led to lifelong, devoted marriages—Jerry and Carole each saw something they wanted and took it, disregarding prior obligations. Were they thefts, or simply the right move? In a clumsy poem, Jerry tried to explain a certain lack in himself:

Extremely painful childhood causes one

To lose his feelings and his principles.

The hurt so great, they shut themselves from it …

No longer do they feel their own distress

And no compassion for another’s pain.

No empathy is felt. But many deep

Unmet needs, as adults do they possess.

There is evidence that Jerry may have submitted false documents to the NYC public school system for the purpose of securing or enhancing a pension. An entry in the school system’s computers for a “J. Alter” who worked at PS 187—the school at which he taught in Washington Heights—identified by the final four digits of a social security number that matches Jerry’s correct social security number—lists Sept. 7, 1977, as his start date, and March 31, 1993, as his end date. This record is false, because in 1977, Jerry had already moved to Cliff. Moreover, there is a second record that was submitted for an “H. Alter” (Jerry’s proper name was Herman Jerome Alter) with start of Dec. 26, 1976, and the same end date—March 31, 1993—for a school in Dyker Heights, Brooklyn, that happens to be located near Jerry’s childhood home. The social security number submitted for this entry included three out of the four final digits of the social submitted for “J. Alter,” and was determined by the authorities to be illegitimate. Carole confirms that Jerry only taught in Washington Heights and never in Brooklyn. Jerry told his nephew Roseman that “he would one day get his pension when his age and years of service hit the ‘magic’ number.”

Theft appears as a theme in Rita Alter’s side of the family as well. Roseman told me that a year after the discovery of the painting in his aunt and uncle’s house, he found out from a long-estranged cousin that Rita and her sister—Roseman’s own mother—had conspired to pilfer the estate of their own mother and keep it for themselves, leaving out their two brothers. “My mother and Aunt Rita saw to it that their brothers would not get anything,” he said. He believes the Cliff house was purchased with money from his grandmother’s estate. “When my grandmother died, it wasn’t a few months before Jerry and Rita bought that place.”

“If you’re able to screw your own brothers out of their inheritance,” he says, “how much further would you have to go to steal something from strangers?”

After the death of Jackson Pollock in 1956, Willem de Kooning was the reigning superstar of the American art scene, which now dominated the world. He was the last fighter standing. It didn’t hurt that he was handsome and photogenic. The writer Lionel Abel wrote that walking with de Kooning through Greenwich Village was like “being with a movie star.” His biographers Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan noted: “… he had a certain way about him, a kind of existential charm that excited New York in the 1950s, when artists and intellectuals liked to discuss the most important subjects in a raspy, tough-guy manner. De Kooning spoke a homemade language, a slightly skewed English with a Dutch accent that was steeped in shoptalk and the American slang that he cherished, but also rich in cryptic allusions and philosophical quips.”

Carole Alter, then an art student at Brooklyn College, lived in the middle of the ferment. She studied from 1952-1956 with such icons as Harry Holtzman, Jimmy Ernst, Kurt Seligman, Alfred Russell, Carl Holty, and Burgoyne Diller. “My favorite was Ad Reinhardt,” she recalls, adding, “I missed out on having Rothko for a teacher. He had left.”

While still an undergraduate, Carole moved out of the family’s Brooklyn home to marry a brilliant German Jewish refugee, Wolfgang Joachim Zuckermann, named for both Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Johann Wolfgang Goethe. An amateur cellist whose family fielded its own string quartet, Wolfgang adored Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann, and Schubert. The rise of the Nazis forced the Zuckermanns to flee Berlin, and they settled in NYC in 1938. “Wallace,” the name he took on arrival in the United States, was 14 years older than Carole, and had already served in the U.S. Army on the front lines with Patton’s regiment. Upon his return stateside, he earned a BA from Queens College, receiving the school’s highest academic undergraduate prize. A polymath, he was a piano tuner and builder, and also a student of child psychology who later became famous for selling build-it-yourself harpsichord kits.

At 18, Carole moved from her parents’ Brooklyn home into a world of bohemian artistic insouciance, brilliance, and ambition, just the world her parents valued and coveted. “My parents loved art and admired artists,” she said. She and Wallace shared an illegal loft on 14th Street and Wallace had “very interesting friends,” including musicians, artists, and Howard Moss, poetry editor of The New Yorker, who purchased one of Wallace’s harpsichords. Jerry watched closely.

In addition to his harpsichord building, which made him famous, Zuckermann wrote books, became an arts promoter, and activist. He was one of the earliest critics of the environmental impact of the internal combustion engine. In opposition to the Vietnam War, he later moved to England and then France, and founded the Librairie Shakespeare English language bookshop in Avignon, France. One day when I asked her about Wallace, Carole decided she was, for the moment, tired of my questions. “You are impressed by Wallace’s accomplishments,” she wrote me in an email. “Why not? I have no impulse to tell you about us, though. … It does me no good to recount my once-thrilling life.”

On a website devoted to Zuckermann, Carole noted that their loft on West 14th Street was destroyed in a fire, and later confirmed to me this was the apartment address on the back of one of the paintings found in the Alter’s house. Was the Matisse-like painting found in the Alter home also hers? Yes. When I showed her photos of other paintings from the Cliff house, she confirmed that she had also painted the de Kooning-like study of a seated woman. When Jerry and Rita moved out West, she recalled, Jerry asked her if he could have them, even though they were just school projects.

It was through a harpsichord tuner that Carole inherited a rent-controlled apartment on West 54th Street because “Wolfgang and I needed a place for me to go when we were at odds.”

Around 1955-56, they were at odds. Jerry noticed Carole’s low mood and decided he knew how to raise her spirits. He came to her apartment on West 54th Street, near the Museum of Modern Art, to give her clarinet lessons. She was willing, and appreciative of his attention, but afraid she might displease him. “He actually had to teach me to read and finger and so on. And I remember being very nervous. Well maybe that’s because I’m nervous. But I remember being worried that Jerry, that a squeak or something, and Jerry would hear it, he was a taskmaster and a perfectionist.”

In the meantime, Jerry was taking full stock of her avante-garde world. “I would have guessed he would think John Cage walking on the stage and not playing the piano was complete crap,” she said. “I would have applauded because I was into it. When William Burroughs would throw some words in the air, I don’t think Jerry would’ve appreciated it—though I would have. He would more likely read Keats and Shelly than Cummings and Ezra Pound. He preferred Wordsworth and that kind of poetry.”

One gallery that was close by her home was the Martha Jackson Gallery on 22 East 66th Street. Carole remembers it clearly. After Willem de Kooning completed “Woman-Ochre” in 1955, Martha Jackson bought the painting and several others. “Woman-Ochre” was displayed in her gallery for two years, part of a one-man show of 21 works. This is the gallery from which, in 1957, the collector Edward Joseph Gallagher Jr. purchased the piece, and soon after donated it to the UA Art Museum. I asked Carole if Jerry liked to go to galleries and museums. “Jerry went to museums more than I did,” she says.

Five years after his own father took up painting, an effort that caught Jerry’s attention enough that years later he wrote a story about it—and during the time Jerry was spending extra time with his painter sister at her apartment on West 54th Street, and just when de Kooning was becoming the talk of the painting crowd, “Woman-Ochre” was exhibited in a gallery near Carole’s house, a gallery she deemed “an important one.”

“Is it possible that Jerry saw the painting there?”

“Yes,” she says.

“Would he have liked it?”

“I don’t think he was envious of those painters and that world. If he were envious of anything it would be the ease at which some people find recognition. He had less luck. Less good luck.”

If Jerry stole the de Kooning many years later, was there a reason he chose that particular painting? Did he feel something special for de Kooning? Had he a memory of its first arrival on the scene at the Martha Jackson Gallery, back in the days when he, too, still had open-ended dreams? Had he seen it with Rita, who he was about to marry? The things he saw early in his life seemed to influence him strongly, as the photos he took on his and Rita’s honeymoon trip to Spain show many design elements he would include in the house they built years later.

Though comparing them in any way feels unseemly—de Kooning was an artist’s artist, overflowing with talent and originality, and Jerry was a dilettante with limited artistic gifts—there are not a few reasons Jerry might have admired de Kooning and perhaps identified with him. They both grew up desperately poor. There was tragedy in both families, and both had mothers who were small with dark hair and dark eyes who wielded their significant feminine attributes to their advantage. Jerry was attached to traditional poetic forms that were being set aside by contemporary tastes, and de Kooning was eviscerated by his colleagues—Pollock for example—for his continued interest in the human figure. Each held onto his preoccupations in spite of changing cultural mores. As de Kooning’s family life in Holland deteriorated, he drifted to the edges of society, even sleeping on barges. When he was 22, he snuck onboard a ship headed to Argentina as a stowaway, jumped ship in New York, and got a job as a house painter in Hoboken. His rise to the top of the art world was slow and painful, marked by disappointments and relentless hard work.

Jerry Alter, if he had read about de Kooning, could not have easily dismissed him as a man who did not deserve his success—or enjoyed undeserved luck. De Kooning struggled and fought for every small success. His first show, when he was 44, was a disaster—not a single painting was sold, he received no notices—but it did not deter him. Unlike many of his fellow painters, de Kooning didn’t develop an early signature style, but rather kept at the exploration of his own truth, in spite of the at-times vociferous criticism. Though the buying public had rejected the work of his first show, his reputation among downtown artists only grew.

Jerry Alter may not have admired the new abstract style, but had he looked deeply, he might have appreciated de Kooning’s determination to battle his way to truth while remaining loyal to the past. It took an immense physical and psychological effort for de Kooning to complete the painting that would eventually be known as “Woman I.” For three years, he painted and scraped off paint, painted and ripped the canvas from the frame, trying to satisfy himself with a painting of a woman. The results were disturbing, ugly to some, even misogynist.

The artist’s biographers Stevens and Swan explain: “When he was a child, de Kooning’s mother often burst into unpredictable and violent rages. A mother who could not be depended upon, who would erupt into furious anger, could well become an idol who must be propitiated and a symbol that no security or trust can be found in this world. (The high heels in many of the Women look like potential weapons.) Even as an adult, de Kooning was unconsciously on guard against the unexpected attack: Conrad Fried once innocently raised his hand, and de Kooning flinched as if he were about to be struck.”

But Stevens and Swan argue that the painting is more than an attempt to propitiate a great power. “‘Woman I’ is the depiction of a relationship,” they wrote. “It suggests two figures locked in a struggle. If the artist himself is not literally described, he is present nonetheless in the slashing and furious brushstroke. The perspective is that of a child looking up at an adult. The calligraphic line, as personal as any in art, dances in furious attendance upon the figure. Yet she remains almost immovable, her outsized eyes and toothy leer seemingly fixed in place while everything around her erupts in mayhem. There is no better suggestion in art of a tantrum, no truer rendering of the child who knows only what he wants—and is desolate—as he hurls himself back and forth against an unyielding strength. … Yet the terror and hatred in ‘Woman I’ are interesting because de Kooning succeeded in conveying, at the same time, so much physical longing. The sculptor Isamu Noguchi once said, rightly, ‘I wonder whether he really hates women. Perhaps he loves them too much..’”

Although Carole describes the family’s great love for husband and father Seymour, there were undercurrents of neglect in the family as well. There was a level of denial that allowed Carole’s Oedipal fantasies to persist unchallenged, and it was also displayed in the family’s reaction to Seymour’s first heart attack. Carole and Mathilda were so shocked by the effect on Seymour’s health, Carole said, that they reacted as if it hadn’t happened. “I’m kind of an unbeliever in many things,” says Carole. “If you tell me you don’t feel very well, I’m like ‘Yeah, she’s not really sick.’ Or maybe it’s not wanting to believe. ... If my father had to lie down, he was malingering.”

One can imagine the teenage Jerry, who identified so strongly with his father, crumbling a little bit more every time his mother and sister mocked his 39-year-old dad when he was forced to catch his breath and rest. In his stories, there is not a small amount of sexual violence—female travelers raped during robberies, violent attacks against women who mistreated his autobiographical characters or did them wrong. The morality of the stories is completely conventional—evil is punished, good prevails, order is maintained—but Jerry is not averse to entertaining thoughts of physical violence against a woman. One wonders if the de Kooning painting touched something deep in him about the confusing tug and unfathomable power of love and attachment.

Jerry and Rita met in 1955 and married in 1957. Like Seymour and Mathilda before them, it was a low-key affair, conducted in the rabbi’s chambers. They lived for a while in Brooklyn, and Rita graduated from City College, and then got a master’s degree in speech pathology. Eventually, they purchased a house in Closter, New Jersey, a pretty suburb of ranch houses, large yards, and copious rhododendrons. It was the first house Jerry had ever lived in. Carole says that Jerry continued to “go to Musician’s Local 802 floor to get club dates, weddings, bar mitzvahs to play on weekends.” He also taught private music lessons in the afternoons, and took lessons himself with Joseph Allard, a renowned sax player.

Jerry wrote a poem about lessons with a famous jazz man, in which the student basically sets up and plays as his teacher takes phone calls and tends to business in another room—completely ignoring him. “So sorry that it took so long/We’ve only got a minute left./For next week, take the foll’wing page,/ The one that has The Marching Song. … My protege is here, please go./Just leave the money on my desk./For only six short years with me,/You’re doing very well, you know!”

Two calls to Musicians’ 802, however, finds no record of gigs booked for Jerry Alter or Herman Jerome Alter or an H. Jerome Alter. Since the union only responds to requests from members, I asked two friends, both professional musicians, to inquire of any records of Jerry Alter getting jobs from Local 802. Both came up with nothing. Perhaps this lack of evidence just meant that Jerry did not work union jobs, but rather smaller, local events.

Jerry himself acknowledged he was not a top-rate jazz player. Said Carole: “He wasn’t a great jazz man and he told me that. The sax—he could play exactly the riffs—somebody else’s— but he said to me he wasn’t inventive enough to create on the spot. He didn’t improvise like that.” Jerry spent hours practicing his clarinet and recording parts on a home tape player, which he mixed together. After listening to some of Jerry’s tapes, Ron Wasserman, the principal bass player for the New York City Ballet Orchestra and founder of Jazzharmonic, says, “there is a distinctive lack of any particular personality or professional sensibility in his sound or phrasing.”

In a poem, “Satan’s Horn,” Jerry wrote:

The saxophone lies gleaming in its case;

A little boy to face an unsure world.

A bond between the two till life is done?

Or but a bagatelle of little note …

And of that boy who’d be quite good, not great,

Regrettably, he strove too hard and long.

That time and effort would have best been spent

In working toward a realistic goal.

In a story, “The Breakfast Clubbers,” Jerry describes the life: “A young couple hiring a band on the basis of an ‘audition’ heard at a bar mitzvah might be flabbergasted to see all different musicians, including the leader, appear at their wedding! This is the nature of the casual engagement field, because most musicians accept the first good offer they receive from any leader, fearing it could be the only one they will receive for a given date.” It was a “very risky way to make a living,” ranging from “almost nothing to a solid middle-class level.”

Jerry, a married man with responsibilities, decided he needed a regular gig to support his family. He got a job teaching music at PS 187 in Washington Heights, where he taught grades 3-6, and ran the orchestra and the glee club. Jerry soon decided he wanted to become an assistant principal, and he studied at night for accreditation at Columbia University. But the promotion didn’t come through as speedily as Jerry wanted. Carole remembers that Jerry’s placement in a school was held back by “affirmative action.” Said Carole, “affirmative action was not affirmative for white teachers. Jerry scored very high on his qualifying exam and expected to get a position—after taking a couple of years of expensive courses at Columbia.” An acquaintance of mine, who also began teaching in the 1960s and who insisted on remaining anonymous because of continuing employment in the school system, said, “At that time, if you were white and Jewish, you could not get promoted.”

At the end of the academic year 1967, according to the memories of a former student, Jerry left his teaching position at PS 187. PS 187 did not return this reporter’s repeated telephone calls or emails attempting to confirm Alter’s employment dates.

Ron Roseman, who as a child spent a lot of time with the family in Closter, remembers Jerry talking about life in the school into the 1970s. “He would tell us stories back when we visited in NJ and how terrible it was and how these middle-schoolers came to school with knives and threatened each other and threatened him. I always thought those stories were current—he told those stories in the mid-’70s, and the context was relevant.” It was Roseman’s belief that Jerry remained employed at PS 187 until he retired. However, according to former students and final assembly programs for PS 187, in 1967, the school only went to sixth grade. The school could not tell me when it added a middle school. Carole says Jerry did not teach anywhere else but in Washington Heights. An end-of-year program for June 1967 shows that Jerry Alter had been replaced as the music teacher by a Mr. Joel Schwartz.

The lack of a promotion angered Jerry. “I’d say it got him upset,” said Carole. “Jobs should be based on your proving yourself. The color of your skin should not have anything to do with it. If you were a Chinese person would you say you can only learn from an Asian person?”

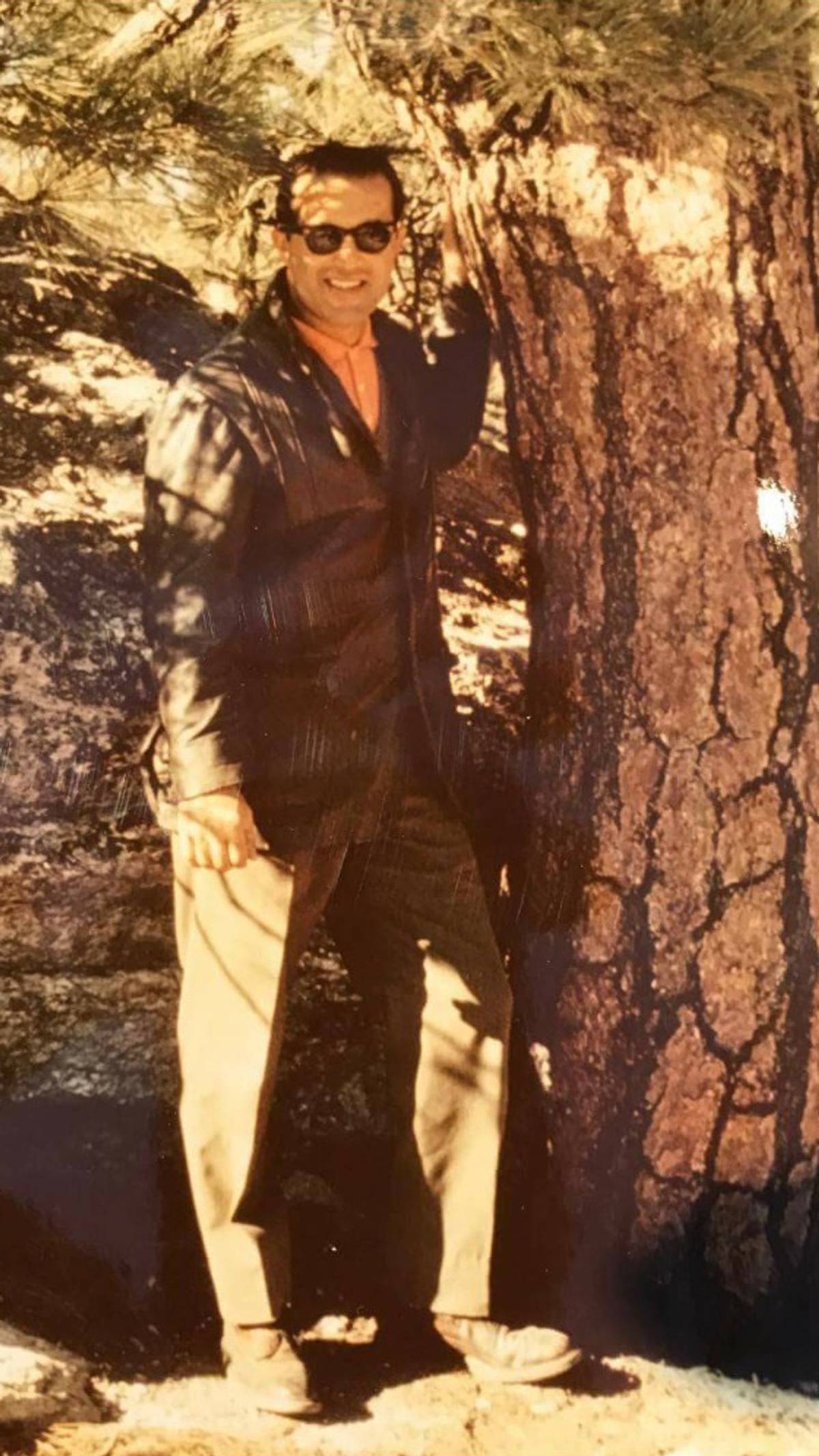

In 1977, Jerry and Rita decided to pack up and go west. They loved to travel, to hike and fish, and they told family members they were “tired of the rat race.” Carole thought Jerry may have explored employment possibilities in California at some time, but nothing came of it. They had vacationed frequently in the Southwest, and for some reason, though I’m sure God will never tell, they found the spot in which they wanted to spend the rest of their lives in Cliff, New Mexico, which is neither a town nor a village but rather a “census designated place.” Jerry and Rita were one of the first to build a house the neighborhood, which was formerly zoned for livestock.

On Nov. 12, 1973, John W. Hooker of Circle H Livestock Company signed a warrantee deed granting 20 acres of land in Cliff, New Mexico, to Jerome and Rita Alter. The sale was recorded on Feb. 14, 1974. The property was part of a larger parcel Hooker owned on a plateau at the edge of the Gila National Forest. According to a story Jerry wrote called “Paradise in View,” which appears to mirror actual events, while first visiting the property he and Rita marveled “at the total silence surrounding them … theirs would be an island, a sanctuary unto itself.” They adored the magnificent view of the Mogollon mountain range in the near distance, which, “unobstructed, stood out against the cobalt sky.” They thought, “we’ve found our dream home!”

According to the rendition in Jerry’s fictionalized story, they were able to get the seller to cut his price by one-third to fit their budget. Although he complied, the seller was not happy about it, and the broker told them so: “It’s a family tradition going back to the original settlers nearly 200 years ago” not to sell land. Nevertheless, he agreed to the deal because he was in financial distress. Sensing the seller’s unhappiness at the closing, “Artie”—the Jerry character—speculated that “Fitzgerald felt he was betraying both his ancestors and his descendants by bringing in an alien entity into their midst.”

But Jerry’s own story adds a nasty twist. After the sale goes through, their home is built, and the couple are living happily ever after in full view of their cherished mountain peaks, one day “Artie” is startled by his wife’s early-morning screams. Two broken-down mobile homes had appeared overnight “not two hundred feet to the north and in direct line with the view.” With the mobile homes came noisy wives, unruly children, barking dogs, and innumerable junked vehicles. “Artie” was outraged by the hubbub and disgusted by the low-class behavior of the new arrivals disturbing his idyll. He assumes Mr. Hooker, peeved by “Artie’s” successful dickering over the price, was serving up his revenge cold.

So, what does Artie do? When the offending neighbors go away for a family reunion, he douses the mobile homes with gasoline, sets them on fire, and burns them to the ground, after taking precautions that no evidence can link him to the crime. Always careful to produce an ending that conforms with standard morality, however, “Artie” later settles with the neighbors, purchasing them modular homes at a different location, close by, but not blocking his view.

Jerry’s self-published collection of stories, The Cup and the Lip, is filled with tales of revenge—against barking dogs (dispatched, to the protagonist’s immense satisfaction, with poison), a nonresponsive literary agent (shot with a tranquilizer dart, kidnapped, then tied half naked to a toilet until she edited every page of his manuscript), and a stone mason who becomes the lover of his wife (killed and stuffed into the septic tank.) There are many gasoline-fueled fires. One of his characters even tries to blow up a beloved rock formation in Arches National Park. “Certainly in his adult life, he had already left a swath of destruction in his wake. Ruined property and devastated lives caused not the slightest upset or pang of conscience in him. Of course, Squire would never commit the sort of overt illegal act sure to bring the police down on him. No, he was too smart for that. He would have to live freely for a very long time in order to exact his revenge on God and mankind for slighting him, for disrespecting him, and for depriving him of his opportunities.” Jerry could never find a publisher for his stories, nor a gallery for his paintings. Gas fires certainly get people’s attention.

Says Olivia Miller of the University of Arizona Art Museum, “The Cup and the Lip is a very disturbing book.”

On Oct. 20, 2017, I set out for Cliff. I hear the Alters’ place is being sold, and I want to look at the gardens and the house before anything is destroyed. Ron Roseman faxes me a handwritten note giving me permission to walk the property. I have heard a police cruiser has been parked at the end of the driveway to keep curiosity seekers away. Along a strip of cheap hotels and signs in Silver City directing tourists toward some ancient Mogollon Indian ruins nearby, I see an old shipping container parked on the side of the road with a sign declaring in faded print: “We buy silver and gold.” I veer off the road. Did Jerry do the same? Could he have chosen Silver City because something familiar beckoned?

I take a short break before the final climb to Cliff and buy a bottle of water. I sit in my vehicle and flip through some letters I received from former students of Jerry’s at PS 187 in Washington Heights. I’m astonished to find that Jerry’s students loved him.

Claudette Laureano writes, “Mr. Alter changed my life forever.” She explains: One day in fifth grade he gave the students a music listening test “to see if we would qualify to play an instrument.” A few days later, he took Claudette aside and told her she was the only student to score 100% on the test, and he recommended she join the band or the orchestra at school. Claudette wrote that she had long (and unsuccessfully) lobbied her parents for piano lessons, and it wasn’t until they learned the results of her music test that they took her request seriously. After a family discussion, they decided she would study violin. “That was how my life-long musical career began,” she wrote. She became a professional violinist and teacher, and now she and her husband run the Minnesota Youth Symphonies. She wrote: “It’s amazing how one person can truly change your life and that is what Mr. Alter did for me.”

Claudette’s younger sister, Leslie, who went on to MIT, says she has a “treasured memory” of Jerry Alter demonstrating proper clarinet playing to her music class while playing along to a “Music Minus One” record—an orchestral accompaniment minus one instrumental part. “It made a huge impression on me, that someone would do that for a bunch of third or fourth (or fifth?) graders.” Different from the students “squeaks and honks” at the end-of-year concerts, “Mr. Alter demonstrated what it COULD sound like. I just remember watching him while he performed, taking his clarinet out of his mouth, breathing, putting it back into his mouth, and the beautiful cascade of notes. This was an unheard of experience for me, to be sitting that close to a musician while he played.”

Nina Beck, who plays in three vocal groups in LA, including her own Nina Beck Trio, described why she and her classmates loved Mr. Alter. “He was positive, motivating, had a love for what he did, smiled a lot, and never had an unkind word.” Most important to his young charges, he created “an overall positive environment with lots of praise & encouragement.”

Karen Luten, now a school teacher herself, writes that her fondest memories came from fourth grade, when Mr. Alter introduced the class to the sounds of the different musical instruments. “I wonder if kids get this sort of education anymore,” she mused. Her favorite moment was a trip to the old Metropolitan Opera House before it closed down. “The Old Met went dark in May 1966—the company moved to Lincoln Center in Sept. 1966,” she wrote. “But that final spring, there were special matinee performances open to all NYC public school students of Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West, and Mr. Alter took us to see it. Making an effort of this kind is not easy—shepherding a bunch of 5th graders down to Lincoln Center and back—but he did it, and I still remember hearing Sherrill Milnes sing the baritone role of Sheriff Jack Rance. I was devastated when Mr. Alter left PS 187 at the end of our 5th grade year.”

I call Carole and tell her about the letters. She begins to cry. “This actually makes me tearful,” she says. “Let me get a tissue because I don’t think that Jerry actually felt appreciation. Unless you hear somebody say, ‘I love you,’ you’re left guessing.”

What does she think disturbed him the most in his life, failing as a musician, or failing to get promoted to supervisor in the NYC public schools?

“How about failing as a father!” she says.

It is 30 more miles northwest on Route 80 to Cliff, where I exit the highway, cross a wash lined with cottonwoods and sycamores, and approach a large outdoor arena and show grounds. Behind it is an elementary school and a high school. This plus a post office and a gas station make up Cliff. I watch a couple boys ride dirt bikes over hilly tracks in the wash. A cowboy trots through on a horse, leading another, on an old riding path that has no relation to the existing roads. It’s still pure country here.

I turn onto Duck Creek Road and drive north a few hundred yards to a small plateau on which there are about a dozen ranch houses and associated barns and outbuildings. At the farthest northern reach of the neighborhood, I get out of the car and open a metal cattle gate to enter the long dirt driveway that leads to 74 Mesa Road. I look around me and breathe in the sweet, warm air. I feel the familiar calm of the high desert and the seduction of its long silences.

I look up at the Alter house, which stands physically apart from the neighborhood that it apparently predated, and off the rectangular grid of its streets. It’s a rambling stucco-covered ranch house with Spanish tile roof and double carport. In front are extensive gardens of evergreens and cactus, surrounded by solidly built low stone walls and featuring pergolas, gates, and arches, also covered with Spanish tile.

I close the cattle gate behind me and drive toward the house. I stop beside a grove of 20-foot juniper trees. When I step out, I find myself face to face with a bust of Plato mounted head high on a fieldstone pedestal. Beside him is Shakespeare. Their plaster selves, once painted black, are peeling in unexpected orange-colored ribbons. Beside them is a double wooden doghouse with “Rocky 1979” written by a child’s finger into the still-wet cement base. A long rusty chain leash lies twisted on the ground.

In 2010, a year before self-publishing his books, and two years before his death from a stroke, Jerry wrote an email to his former elementary school student Nina Beck after coming across a photo of himself on her website. He explained that looking at an old photo album had reminded him of her, and his wife had then Googled her. “Hello Nina,” he wrote, “This guy, once young, is me. But is this lassie you? Jerry Alter.” In the ensuing email correspondence, he described his life: “After an early retirement, prompted by a loss of opportunity for me in the NYC School System, we moved to a 20-acre property in a mountain valley, surrounded by ranch land. With our own hands, we built the attractive house in which we still live. With a large swimming pool and extensive gardens, it’s the showplace of the area! (Please pardon my modesty.) We have 2 children not much younger than you are, and 4 grandchildren.”

Lori Williams, who lives directly across the street from the Alters, who moved here in 1998, told me earlier on the telephone, “I never in all my years except for one time heard them say anything about their children, ever. The kids were gone when we moved here. They were never here. With the exception of the meter reader, no one ever went there. They were quite reclusive. Friendly on the outside. But no family.”

After purchasing the property in 1973, the Alters had a well dug, and in 1977 left Closter, bought a trailer, moved it and their family onto the land, and proceeded to build the house. Their son, Joey, born on June 6, 1962, would have been 15, and his little sister, Barbara, born 13 months after him on July 9, 1963, was 14. Roseman says before they left, Joey was bar mitzvahed at a Reform temple in Closter that no longer exists. Rita soon got a job as a speech therapist in the Cliff and Silver schools, helping young children with speech problems. Says Frances Vasquez who worked in the office with her, “She was a nice lady. Rita was just Rita. At every party at school, she made thumbprint cookies and at Christmas time, even though she was Jewish and didn’t celebrate Christmas, she gave all the girls in the office a box of chocolate-covered cherries.”

Jerry and Rita were known as friendly but private, a couple who used all their free time traveling. Most of their contact with their neighbors came when they were out walking. “They were avid walkers,” said neighbor Williams, who sells civil engineering software. “When we drove by them, we would always stop and chat. They were cordial and friendly.”

Lori Williams says the Alters invited her and her husband over one night for dinner. “It was nice. At the end of dinner, Jerry asked us if we wanted to listen to him read some poetry. He pulled out a manuscript.” I asked how Jerry read—calm? Quiet? Animated?

“Spit flying out of his mouth and everything. Very theatrical. My husband and I tried not to laugh.”

But what she will never forget is Rita: “with her elbows on the table, face on her hands, hands under her chin dreamy-eyed, gazing at Jerry and hanging on his every word like a lovesick school girl.” Even years after Jerry’s death, she was still grieving. “Rita would say, when I bumped into her, ‘Oh I still incredibly miss Jerry.’ You could see the heartbreak.” Jerry wrote on the dedication page of The Cup and the Lip: “It’s only right that I dedicate this book to my lovely wife Rita. After all, she has dedicated her whole life to me.” Says Williams: “She was just very intent, extremely devoted to Jerry. If he asked Rita to commit murder, she probably would have.”

I enter the garden through a covered arch and read a few lines of poetry that Jerry had burned, possibly with a magnifying glass, onto a wood panel, then stained and varnished: “The Garden of Syrinx/And Pan did after Syrinx speed,/Not for a Nymph, but for a reed.” It is from Andrew Marvel’s “The Garden.” My knowledge of 17th-century English poetry is limited, but I see the classical references to Apollo and Daphne and sense a hint of its story of sexual violence. Neat walking paths of white stone form exact geometric shapes within the darker volcanic stones that cover the garden beds. Here and there are small pavilions and sitting areas, decorated with sculptures (a mosaic pyramid, some mirrored globes), and abstract paintings painted by Jerry, many of which filled the house, according to Dave Van Auker.

I come across a shelter marked as a shrine to Apollo, decorated with a plaster bust of the sun god and a statue of Pan. There are sitting areas with wrought-iron garden chairs covered with water-resistant floral upholstered outdoor seats. And more poetry. Here are some lines from John Keats: “A thing of beauty is a joy forever,/Its loveliness increases./It will never pass into nothingness.” And a few verses from “Stardust,” one of Jerry’s favorite songs, which he loved to play on the clarinet: “Beside the garden wall / When stars are bright / You are in my arms.”

A path leads me to a fountain surrounded by a ring of busts of classical composers, again, head high, mounted on pillars. It is not exactly the Vienna Central Cemetery where monuments to Brahms, Schubert, and Beethoven commune in a peaceful grove. Here, we have likenesses of Bach, Brahms, Beethoven, and Mozart, arranged like sacrificial totems around a low stone wall that encircles a now-broken fountain filled in with lava rock. I am feeling restless, slightly irritable. This is not a garden celebrating art and thought and music. It is a crazy garden, celebrating crazy.

Jerry Alter needed to show the world he existed; he needed to release himself from his prison of impotence.

I look around me—at the dry scrub, and the intense, ambitious, but tone-deaf worship of “culture.” It was created as an homage to all Jerry held dear, and presumably, as a place to rest and contemplate the highest expressions of beauty. But it is not beautiful here. The paintings and mosaics are effortful, but ugly. And the garden has little relation to the softly undulating landscape or the rise of the distant peaks. I think of a story Jerry wrote about an unsuccessful club musician. He “sounded great,” Jerry wrote, “but didn’t have a clue what to play for the people. There could be a floor full of dancers when it was his turn to play something, but by the time he finished, there wasn’t a soul left dancing.”