At the time of the Dreyfus affair, many members of the artistic avant-garde took sides: Monet and Pissarro, with their old friend and supporter Zola, were Dreyfusard, or pro-Dreyfus, as were the younger radical artists Luce, Signac, and Vallotton and the American Mary Cassatt; Cézanne, Rodin, Renoir, and Degas were anti-Dreyfusard. Monet, who had been out of touch with Zola for several years, nevertheless wrote to his old friend two days after the appearance of “J’accuse” to congratulate him for his valor and his courage; on 18 January, Monet signed the so-called Manifesto of the Intellectuals on Dreyfus’ behalf. Despite the fact that at the outset of the affair many anarchists were unfavorably disposed toward Dreyfus—an army officer and wealthy to boot—Pissarro, who was an ardent anarchist, nevertheless quickly became convinced of his innocence. He too wrote to Zola after the appearance of “J’accuse,” to congratulate him for his “great courage” and “nobility of … character,” signing the letter, “Your old comrade.” Renoir, who managed to keep up with some of his Jewish friends like the Natansons at the height of the affair, nevertheless was both an anti-Dreyfusard and openly anti-Semitic, a position obviously linked to his deep political conservatism and fear of anarchism. Of the Jews, he maintained that there was a reason for their being kicked out of every country, and asserted that “they shouldn’t be allowed to become so important in France.” He spoke out against his old friend Pissarro, saying that his sons had failed to do their military service because they lacked ties to their country. Earlier, in 1882, he had protested against showing his work with Pissarro, maintaining that “to exhibit with the Jew Pissarro means revolution.”

None of the former Impressionists, however, was as ardently anti-Dreyfusard and, it would seem, as anti-Semitic as Edgar Degas. When a model in Degas’ studio expressed doubt that Dreyfus was guilty, Degas screamed at her “you are Jewish … you are Jewish …” and ordered her to put on her clothes and leave, even though he was told that the woman was actually Protestant. Pissarro, who continued to admire Degas’ work, referred to him in a note to Lucien as “the ferocious anti-Semite.” He later told his friend Signac that since the anti-Semitic incidents of 1898, Degas, and Renoir as well, shunned him. Degas, at the height of the affair, even went so far as to suggest that Pissarro’s painting was ignoble; when reminded that he had once thought highly of his old friend’s work he replied, “Yes, but that was before the Dreyfus affair.”

Such anecdotes provide us with a bare indication of the facts concerning vanguard artists and the Dreyfus affair, and they tend to create an oversimplified impression of an extremely complex historical situation. Certainly, there seems to be little evidence in the art of any of these artists, of such essentially political attitudes as anti-Semitism or Dreyfusard sympathies. Yet there are certain ways of reading the admittedly rather limited visual evidence that can lead to a more sophisticated analysis of the issues involved. Two concrete images reveal, better than any elaborate theoretical explanation, the complexity of the relation of vanguard artists to Jews and “Jewishness” and, at the same time, the equally complex relation which obtains between visual representation and meaning. The first, a work in pastel and tempera on paper of 1879, is by Edgar Degas, and it represents Ludovic Halévy, the artist’s boyhood friend and constant companion, writer, librettist, and man-about-town. Halévy is shown backstage at the opera with another close friend, Boulanger-Cavé. The image is a poignant one. The inwardness of mood and the isolation of the figure of Halévy, silhouetted against the vital brilliance of the yellowish blue-green backdrop, suggest an empathy between the middle-aged artist and his equally middle-aged subject, who leans, with a kind of resigned nonchalance, against his furled umbrella. The gaiety and make-believe of the theater setting only serves as a foil to set off the essential solitude, the sense of worldly weariness, established by Halévy’s figure. Halévy himself commented on this discrepancy between mood and setting in the pages of his journal: “Myself, serious in a frivolous place: That’s what Degas wanted to represent.” The only touch of bright color on the figures is provided by the tiny dab of red at both men’s lapels: the ribbon of the Legion of Honor, glowing like an ember in the dark, signifying with Degas’ customary laconicism the distinction appropriate to members of his intimate circle—though Degas himself viewed such institutional accolades rather coolly. Halévy, of course, was a Jew; a convert to Catholicism, to be sure, but a Jew, nevertheless, and when the time came, a staunch Dreyfusard. His son, Daniel, one of Degas’ most fervent admirers, was to be, with his friend Charles Peguy, one of the most fervent of Dreyfus’ defenders. No one looking at this sympathetic, indeed empathetic, portrait would surmise that Degas was (or would become) an anti-Semite or that he would become a virulent anti-Dreyfusard; indeed, that within 10 years, he would pay his last visit to the Halévys home, which had been like his own for many years, and never return again, except briefly, on Ludovic’s death in 1908, to pay his final respects.

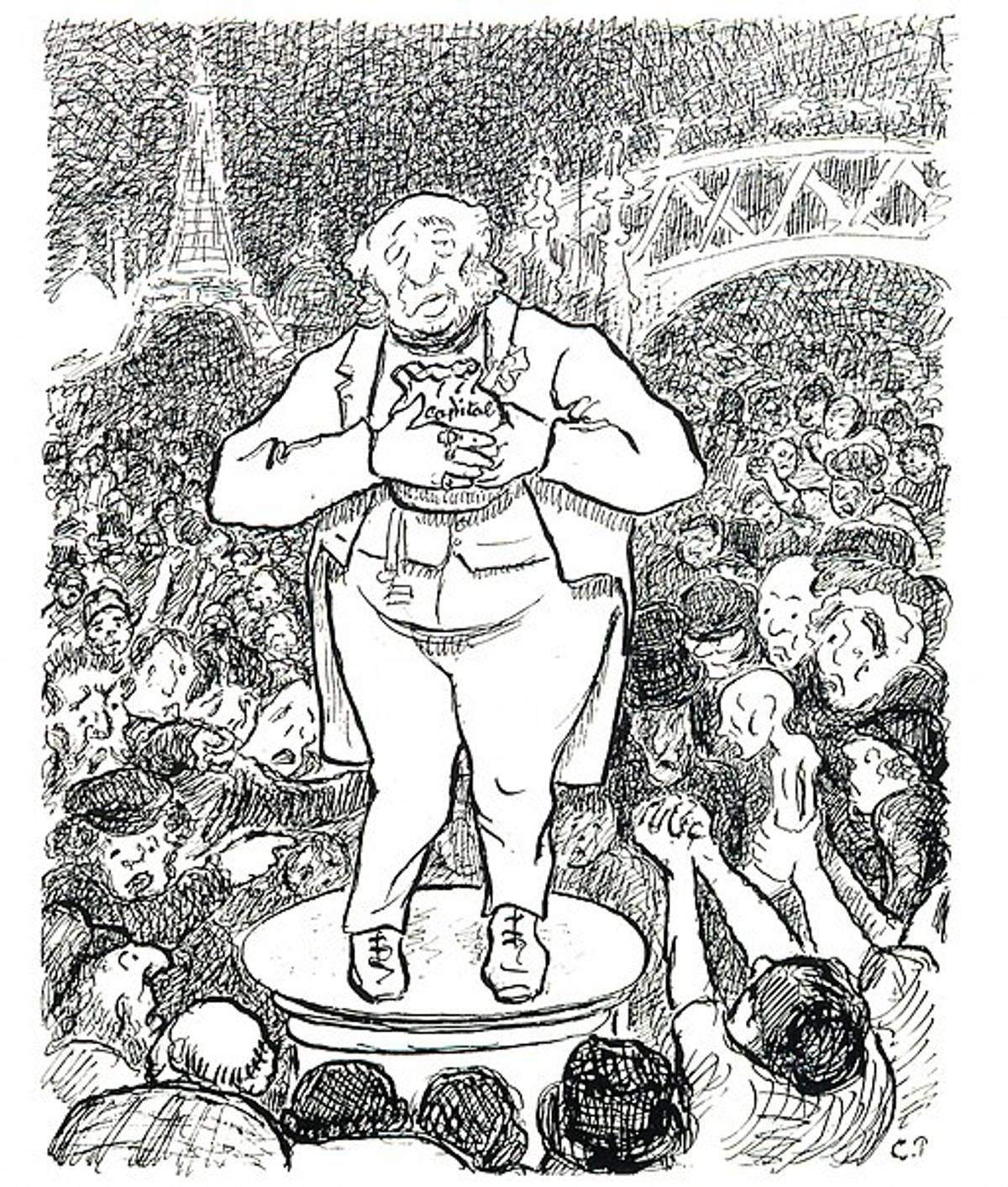

The second image to consider is a pen-and-ink drawing, one of a series of 28 by Camille Pissarro titled Les Turpitudes Sociales. Created in 1889, the series, representing both the exploiters and the exploited of his time was intended for the political education of his nieces Esther and Alice Isaacson. The drawing in question is titled “Capital” and represents, in a highly caricatural style, reminiscent of Daumier or the English graphic artist Charles Keene, the statue of a fat banker clutching a bag of gold to his heart. The features of the figure—the prominent hooked nose, protruding cars, thick lips, slack pot belly, soft hands, and knock-knees—could almost serve as an illustration for the description of the prototypical Jew concocted by the anti-Semitic agitator Drumont. In a letter accompanying Les Turpitudes Sociales, Pissarro describes this drawing as follows: “The statue is the golden calf, the God Capital. In a word it represents the divinity of the day in a portrait of a Bischoffheim [sic], of an Oppenheim, of a Rothschild, of a Gould, whatever. It is without distinction, vulgar and ugly.” Lest we think that this stereotypically Jewish caricature glossed by a list of specifically Jewish names is a mere coincidence, figures with the exaggeratedly hooked noses used to pillory Jews appear prominently in the foreground of another drawing from the series, “The Temple of the Golden Calf,” a representation of a crowd of speculators in front of the bourse. A third drawing, originally intended for the Turpitudes Sociales album but then omitted, is even more overtly anti-Semitic in its choice of figure type. The drawing represents the golden calf being borne in procession by four top-hatted capitalists, the first two of whom arc shown with grotesquely exaggerated Jewish-looking features, while several long-nosed attendants follow behind in the cortege. The whole scene is observed by a group of working-class figures with awed expressions.

It is hard for the modern viewer to connect these anti-Semitic drawings with what we know about Pissarro: the fact that he was, after all, a Jew himself; that he was an anarchist; that he was an extremely generous and unprejudiced person; and, above all, with the fact that when the time came he became a staunch supporter of Dreyfus and the Dreyfusard cause. Yet lest we reach the paradoxical conclusion that the anti-Dreyfusard Degas was more sympathetic to his Jewish subjects than the Jewish Dreyfusard Pissarro, one must examine further both the art and the attitudes of the two artists. What, for instance, are we to make of a Degas painting, almost contemporary with the Halévy portrait, titled “At the Bourse”? It represents the Jewish banker, speculator, and patron of the arts, Ernest May, on the steps of the stock exchange in company with a certain M. Bolatre. At first glance, the painting seems quite similar to the “Friends on the Stage”, even to the way Degas has used some brilliantly streaked paint on the dado to the left to set off the black-clad figures. But if we look further, we see that this is not quite the case. The gestures, the features, and the positioning of the figures suggest something quite different from the distinction and empathetic identification characteristic of the Halévy portrait: What they suggest is “Jewishness” in an unflattering, if relatively subtle way. If “At the Bourse” does not sink to the level of anti-Semitic caricature, like the drawings from Les Turpitudes Sociales, it nevertheless draws from the same polluted source of available visual stereotypes. Its subtlety owes something to the fact that it is conceived as “a work of art” rather than a “mere caricature.” It is not so much May’s Semitic features, but rather the gesture that I find disturbing—what might be called the “confidential touching”—that and the rather strange, close-up angle of vision from which the artist chose to record it, as though to suggest that the spectator is spying on rather than merely looking at the transaction taking place. At this point in Degas’ career, gesture and the vantage point from which gesture was recorded were everything in his creation of an accurate, seemingly unmediated, imagery of modern life. “A back should reveal temperament, age, and social position, a pair of hands should reveal the magistrate or the merchant, and a gesture should reveal an entire range of feelings,” the critic Edmond Duranty declared in the discussion of Degas from his polemical account of the nascent Impressionist group, “The New Painting” (1876). What is “revealed” here, perhaps unconsciously, through May’s gesture, as well as the unseemly, inelegant closeness of the two central figures and the demeanor of the vaguely adumbrated supporting cast of characters, like the odd couple, one with a “Semitic nose,” pressed as tightly as lovers into the narrow space at the left-hand margin of the picture, is a whole mythology of Jewish financial conspiracy. That gesture—the half-hidden head tilted to afford greater intimacy, the plump white hand on the slightly raised shoulder, the stiff turn of May’s head, the somewhat emphasized ear picking up the tip—all this, in the context of the half-precise, half-merely adumbrated background, suggests “insider” information to which “they,” are privy, from which “we,” the spectators (understood to be gentile) are excluded. This is, in effect, the representation of a conspiracy. It is not too farfetched to think of the traditional gesture of Judas betraying Christ in this connection, except that here, both figures function to signify Judas; Christ, of course, is the French public, betrayed by Jewish financial machinations.

I am talking, of course, of significances inscribed, for the most part unconsciously or only half-consciously, in this vignette of modern commerce. If my reading seems a little paranoid, one might compare the gesture uniting the Jewish May and his friend with any of those in Degas’ portraits of members of his own family who, after all, were also engaged in commerce-banking on the paternal side, the cotton market on his mother’s. There is never the slightest overtone of what might be thought of as the “vulgar familiarity” characteristic of the gesture of May and Bolatre in their images. Instead, Degas’ family portraits, like “The Bellelli Family” or, in a very different vein, “The Cotton Market in New Orleans,” suggest either aristocratic distinction or down-to-earth openness of professional engagement.

Yet I am not suggesting that Degas was an anti-Semite simply through my reading of a single portrait any more than I would suggest that Pissarro was an anti-Semite because of the existence of a few drawings with nefarious capitalists cast in the imagery of Jewish stereotype. The real evidence for anti-Semitism, in Degas’ case, or against it in Pissarro’s is both more straightforward and, as far as Degas is concerned, more contradictory. Both artists reenact scenarios of their class and class-fraction positions; both of their practices in relation to what might be called the “signifying system” of the Dreyfus affair are fraught with inconsistencies: They are not total, rational systems of behavior but rather fluctuating and fissured responses, changing over time, deeply rooted in class and family positions but never identical with them.

Let us start to look at the evidence for Degas’ attitudes toward Jews, Jewishness, and the Dreyfus affair in greater detail, keeping in mind the fact that the Degas who sided with the anti-Dreyfusards in the late ’90s was no longer the same Degas who sympathized with the fate of the vanquished Communards in 1871 or worked with the Jewish Pissarro in the ’80s. Attitudes change over time, vague propensities stiffen into positions; events may serve as potent catalysts for extremist stances.

First, then, evidence of what might be called “pro-Jewish” attitudes and behavior on Degas’ part prior to the Dreyfus affair—and there is a good deal of it. It is, to begin with, undeniable that Degas’ circle of intimate friends, as well as that of his acquaintances, included many Jews, not merely Ludovic Halévy, and his son, Daniel, who, as a young man, worshiped Degas, but Halévy’s cousin Genevieve, daughter of his uncle Fromenthal and widow of Georges Bizet, who, as Mme. Straus, wife of a lawyer for the Rothschild interests, ran one of the important Parisian salons of the later 19th century. The Halévy circle included such prominent Jewish figures as Ernest Reyer, the music critic for Le Journal des Debats; Charles Ephrussi, founder of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts; and Charles Haas, the elegant Jewish man-about-town who served as a model for Proust’s Swann. And of course, Degas was intimately associated with the Jewish artist Pissarro, both in connection with the organization of the Impressionist exhibitions, in which both played an important role and to which both exhibited untiring loyalty, but also in the practice of printmaking later. Degas was one of the first to have bought Pissarro’s paintings, and Pissarro admired Degas above all the other Impressionists, maintaining that he was “without doubt the greatest artist of the period.”

Indeed, it would have been difficult to participate in the vanguard art world of the later 19th century without coming into contact with Jews in one way or another; even so, the number of Degas’ Jewish friends and acquaintances was unusually large. It is equally undeniable that he portrayed a considerable number of Jewish sitters. In addition to the depictions of Halévy and May considered above, there are such portraits as those of a painter friend, Emile Levy (1826-1890), a study for which dates from August 1865-1869; M. Brandon, father of the painter Edouard Brandon (1831-1897), who was also a friend of Degas’, of the mid-’70s; and the “Portrait of the Painter Henri Michel-Levy” (1844-1914), another friend of Degas’, with whom he exchanged portraits. The painter, a minor Impressionist, son of a wealthy publisher, is represented slouching rather morosely in the corner of his studio, with a large mannequin at his feet and his paintings on the walls behind. Degas, in his letters, mentions sketches for a portrait of Charles Ephrussi, but the work itself has not been identified. Perhaps most surprising of all, in view of Degas’ later political stance, there is the double portrait of “Rabbi Elie-Aristide Astruc and General Emile Mellinet” of 1871. Astruc, an authority on Judaic history, was chief rabbi of Belgium and assistant to the chief rabbi of Paris. Mellinet, a staunch republican, anticlerical, and Freemason, worked with Astruc in the ambulance service during the siege of Paris caring for the wounded. They asked Degas to paint them together to “recall their fraternal effort.” The result is a striking little picture, loosely handled, casual and unpretentious, in which Degas, although emphasizing the comradely unity between the two men, nevertheless brings out contrasts of age, type, and character by means of subtle elements of composition and quite striking ones of color.

Yet it is the Halévys who figure over and over again in Degas’ work, both as subject and as site, as it were, of his practice as an artist. “We have made him,” declared Daniel Halévy in his journal in 1890, “not just an intimate friend but a member of our family, his own being scattered all over the world.” It could, of course, be maintained, that as completely assimilated Jews, Halévy and his sons could hardly be considered “Jewish” at all. While it is true that Ludovic Halévy does not talk about his Jewishness in the pages of his carnets, and seems to have been without any particular religious beliefs or practices, there is at least one piece of evidence, long before the Dreyfus affair brought him to greater self-consciousness and activism, that Ludovic Halévy in fact considered himself to be, irrevocably, a Jew. That evidence is in the form of a letter that appeared in the Archives israélites, a publication dedicated to Jewish political and religious affairs, in 1883, a time when Degas was having Thursday dinner and two or three lunches a week with Ludovic Halévy and his family at 22 rue de Douai. The occasion of the letter was an obituary for Ludovic’s father, Leon Halévy. After thanking the editor for the articles, Halévy states: “You are perfectly right to think and say that the moral link between myself and the Jewish community has not been broken. I feel myself to be and will always feel myself to be of the Jewish race. And it is certainly not the present circumstances, not these odious persecutions [the current pogroms in Russia and Hungary] that will weaken such a feeling in my soul. On the contrary, they only strengthen it.”

Although Halévy may have been guarded about expressing such sentiments to Degas, it is hardly likely that the artist could have been completely unaware of them—or of the fact that, from an anti-Semite’s point of view, his close, indeed, one of his closest, friends was a Jew “by race,” whether or not Halévy chose to be one. If Degas were in fact, an anti-Semite at this time, it would appear that the virus was in a state of extreme latency, visible only in the nuances of a few works of art and intermittently at that. Or perhaps one might say that before the period of the Dreyfus affair, Degas, like many other Frenchmen and women, and even like his erstwhile Impressionist comrade, Pissarro, was anti-Jewish only in terms of a certain representation of the Jew or of particular “Jewish traits,” but his attitude did not yet manifest itself in overt hostility toward actual Jewish people, nor did it yet take the form of a coherent ideology of anti-Semitism.

In the case of the Halévys, Degas felt enough at home among them to work as well as to enjoy himself in their affectionate company. It was at their house on the rue de Douai that Degas made the drawings contained in the two large “Halévy Sketchbooks,” in one of which Ludovic Halévy wrote: “All the sketches of this album were made at my house by Degas.” The Halévys made frequent appearances in Degas’ oeuvre. Besides the backstage portrait discussed above, both Ludovic and his son Daniel figure in one of Degas’ most complicated group portraits, “Six Friends at Dieppe,” a pastel made in 1885, during a visit to the Halévys at this seaside resort. It is a strange picture. Most of the sitters’ are jammed against the right-hand margin, and Degas was not flattering to many of his subjects. The sitters include Halévy’s son, Daniel, peeking out at the spectator from under a straw boater; the English painter Walter Sickert; the French artists Henri Gervex and Jacques-Emile Blanche; and Cave, “the man of taste,” as Degas called him, whom the artist had portrayed before with Halévy behind the scenes at the opera. In this rather heterogeneous company, Ludovic Halévy stands out as a special case. As Jean Sutherland Boggs put it: “In the noble head of the bearded Halévy in the upper right of the pastel we can suspect a possible idealization which would reveal the easily satirical Degas’ admiration and respect.”

At other times, however, Degas seems to have been less respectful of his old friend, most notably in the series of monotype illustrations he created for Halévy’s light-hearted but pointed satire of backstage mothers and upwardly mobile young ballet dancers, La Famille Cardinal, in the late ’70s. Taking Halévy’s first-person narration quite literally, Degas has his friend appear in at least nine of the compositions, most notably in the one titled “Ludovic Halévy Meeting Mme. Cardinal Backstage.” Here, Degas’ mischievous sense of caricature and his synoptic, suggestive drawing style are put to good use in the way he contrasts the stiff, reticent pose of the narrator with the more vulgar expansiveness of the mother of the two young dancers, whose careers, on stage and off, is the subject of the book. In another illustration, it is Degas himself, perhaps, who chats with the girls in the company of Halévy and another gentleman backstage; in still another, Halévy visits Madame Cardinal in the dressing room. Halévy evidently failed to appreciate Degas’ illustrations, and his refusal to accept them for publication evidently put some strain on their friendship. Various reasons have been put forth for Halévy’s displeasure: The author is said to have thought Degas’ illustrations to have been “too idiosyncratic” or “more a recreation of the spirit and ambience of Halévy’s book than authentic illustrations.” While both these reasons may be true, it seems to me that other considerations may also have figured in Halévy’s rejection of his friend’s pictures: that in some of them, he appears too engaged, too much a part rather than a mere spectator, of the rather louche business of selling young women’s bodies behind the scenes at the opera. Did Halévy notice a disturbing resemblance between himself, as represented in the Famille Cardinal monotypes, and the single male visitor, leaning on a cane or umbrella, who is a constant, though often partial, presence in the famous brothel monotypes of the same period, monotypes which the Famille Cardinal prints often resemble so closely? Degas was perhaps not reticent enough in suggesting, through visual similarity, a more material connection between the life of the ballet dancer and that of the prostitute, plain and simple, than Halévy had been willing to make explicit in his light-hearted text about parental venality and female availability. And as a final reason for the author’s rejection of his friend’s illustrations, is it too far-fetched to suppose that Halévy saw a fleeting resemblance between himself as represented by Degas in the Cardinal monotypes and some of the coarse Semitic featured “protectors” who appeared leering down the décolletages of ballet girls in caricatures of the time? Obviously, a certain amount of tension existed between Halévy and Degas, as it so often does in extremely close male friendships, where a competitive relation with the world may conflict with intense intimacy. Love and hate, support and antagonism are often not so far apart. Clearly, Degas’ representation of Halévy in the Cardinal illustrations is a quite different, and more ambiguous, one than that embodied in the “noble head” from the Dieppe group portrait.

The Halévys also played a significant role in Degas’ intense if not always successful engagement with photography. Not only did Ludovic’s wife, Louise, serve as the developer of his plates—he jokingly referred to her as “Louise la reveleuse” in one of his letters—but members of the Halévy family posed for many of his prints and photographed tableaux vivants, among them the memorable parody of Ingres’ “Apotheosis of Homer,” in which the two “choirboys,” as Degas called them, worshiping in the foreground are Elie seemed to have any political opinions.” Daniel Halévy describes the circumstances of the break in considerable detail: “Thursday, 25 November 1897. Last night, chatting among ourselves at the end of the evening—until then the subject [the Dreyfus affair and Daniel Halévy].” In addition, Degas photographed Daniel Halévy, in a thoughtful pose, seated in an armchair, his hand supporting his chin; Mme. Ludovic Halévy, pensive, in the same antimacassar-backed armchair; Elie in a leather chair with his mother reclining on a nearby sofa, several intriguing pictures of ballet dancers on the wall behind them. In another photograph, Ludovic is featured in a double exposure with other members of his family.

All this came to an end, more or less abruptly, as the time of the Dreyfus affair. As Daniel Halévy wrote: “An almost unbelievable thing happened in the autumn of 1897. Our long-standing friendship with Degas, which on our mother’s side went back to their childhood, was broken off. Nothing in our past relationship indicated that politics could cause such a break. Degas never had been proscribed as Papa was on edge, Degas very anti-Semitic—we had a few moments of delightful gaiety and relaxation. … It was the last of our happy conversations,” Daniel Halévy declares in his retrospective commentary on this journal entry. “Our friendship was to end suddenly and in silence. … One last time Degas dined with us … Degas remained silent. … His lips were closed; he looked upwards almost constantly as though cutting himself off from the company that surrounded him. Had he spoken it would no doubt have been in defense of the army, the army whose traditions and virtues he held so high, and which was now being insulted by our intellectual theorizing. Not a word came from those closed lips, and at the end of dinner Degas disappeared.”

The break with the Halévys was in many ways less sudden than it appeared; nor could it be attributed solely to the intensification of the Dreyfus affair at the time it occurred, although without the affair, it might not have taken place. One might almost liken the process of becoming an anti-Semite to that of falling in love, a process, according to Stendahl, in his famous essay on the subject, culminating in “crystallization”; anti-Semitism may perhaps be thought of as “falling in hate,” a process in which all the negative structures come together, and the subject assumes a new identity vis-à-vis the Other. This requires an often startling redefinition of former friends and associates: for example, in Degas’ case, of Pissarro, with whom he had worked, whom he had admired and who admired him in return, or of Ludovic Halévy. The Dreyfus affair was, of course, one of these crystallizing agencies, pushing equivocators over the brink, spurring to action people like Degas who before had perhaps merely grumbled and read Drumont with a certain degree of approval, but who didn’t have a cause until the affair served as a catalyst.

By 1895, Degas was already, in addition to being a violent nationalist and uncritical supporter of the army, an outspoken anti-Semite. He had begun to have his maid Zoe read aloud at the breakfast table from Drumont’s La Libre Parole and from Rochefort’s scurrilous L’Intransigeant, which he thought was “full of a miraculous sort of good sense.” He became closer to people who shared his ideas: the painter Forain, who viciously caricatured the Dreyfusards in the weekly Psst …; his old friend Henri Rouart, and the four Rouart sons, the latter of whom were anti-Dreyfusard extremists. With such companions, the aging Degas could, so to speak, let himself go: “In the town house in the Rue de Lisbonne [the Rouarts’ home) Monsieur Degas was completely himself. … With people of whose friendship he was sure, he unbridled his frenzy as a dispenser of condemnations, as a fanatic, as a flag-waver from a past era. The others humored him in his manias and shared his prejudices.”

Degas, as a devoted follower of La Libre Parole, must have read the so-called Monument Henry, published in its pages in 1898-99. This was a subscription on behalf of the widow and child of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry, who had committed suicide when his fabrication of evidence incriminating Dreyfus was discovered, and who was made into a martyr of the anti-Dreyfusard cause; many subscribers sent overtly anti-Semitic messages along with their donations. One wonders what Degas made of them, how he managed to reconcile these obscenities with his actual experience of Jewish friends and supporters. Did Degas think of Ludovic Halévy when Zoe read to him at the breakfast table such sentiments as “for God, the Nation and the extermination of the Jews” or “for the expulsion of the race of traitors” or “French honor against Jewish gold”? Did he think of the happy evenings spent at the rue de Douai when he read the comment from an inhabitant of Baccarat “who would like to see all the yids, yiddesses and their brats in the locality burned in the glass furnaces here”? Did he think of Pissarro, once his companion in the Impressionist venture, his fellow experimenter in new printmaking techniques, and one of his most sincere admirers, when he read the numerous entries, such as the following, betraying what Stephen Wilson has termed “personal sadistic involvement in detailed tortures …”? “A military doctor … who wishes that vivisection were practiced on Jews rather than on harmless rabbits”; or this: “a group of officers on active service. To buy nails to crucify the Jews.” Or this: “to make a dog’s meal by boiling up certain noses”? Or, for that matter, what might Degas, an artist deeply concerned about his own rapidly failing vision, have thought about the anti-Dreyfusard donor from Le Mans who “would like all Jews to have their eyes put out”? Or what might his reaction have been to the highly imaginative recommendation, again involving eyes and blinding, offered by Rochefort in the pages of L’Intransigeant in October of 1898 for the treatment of the magistrates who purportedly favored revision of the Dreyfus case: “A specially trained torturer should first of all cut off their eyelids with a pair of scissors. … When it is thus quite impossible for them to close their eyes, poisonous spiders will be put in the half shells of walnuts, which will be placed on their eyes, and these will be securely fixed by strings tied round their heads. The hungry spiders, which are not too choosy about what they eat, will then gnaw slowly through the cornea and into the eye, until nothing is left in the blind sockets.” One would like to think that Degas was horrified or contemptuous of such grotesque lucubrations, which, for the modern reader, have clear sexual connotations in their use of eye symbolism, yet there is nothing to suggest that he was: On the contrary, Degas was a faithful reader of both journals, and evidently agreed with and took satisfaction in what they printed.

One must conclude that although Degas was indeed an extraordinary artist, a brilliant innovator, and one of the most important figures in the artistic vanguard of the 19th century, he was a perfectly ordinary anti-Semite. As such, he must have been capable of amazing feats of both irrationality and rationalization, able to keep different parts of his inner and outer life in separate compartments in order to construct for himself what Sartre has referred to as a personality with the “permanence of rock,” a morality “of petrified values,” and an identity of “pitiless stone,” choices, according to Sartre, constitutive of the anti-Semite. To comprehend the mechanisms of Degas’ anti-Semitism, one must conceive of the processes of displacement and condensation taking place on the level of the political unconscious functioning in a manner not dissimilar to those of the dreamwork on the level of the individual psyche, processes in which contradictory elements can be effortlessly amalgamated, painful conflicts torn asunder and safely kept apart. The sleep of reason produces monsters, and “The Jew” was produced in the sleep of Enlightenment ideals of reason and truth and justice, in the minds of 19th-century anti-Semites like Degas, secure in the knowledge that most of their more outrageous aggression-fantasies would be fulfilled on the level of text rather than in practice. Text is the key word here. For it was editors, columnists, and pamphleteers who constructed the anti-Semitic identity of men like Degas. Without the discourse of the popular press books, pamphlets, and journals, some of it to be sure with high claims to “intellectual distinction” and “scientific objectivity,” which formulated and stimulated it, Degas’ anti-Semitism would be unthinkable. It was at the level of the printed word that anti-Semitism, flowing from, yet at the same time fueling the fantasies of the individual psyche, achieved a social existence and took a collective form.

There was a specific aspect of Degas’ situation in the world that might have made him particularly susceptible to the anti-Semitic ideology of his time: what might be called his “status anxiety.” According to Stephen Wilson: “The French anti-Semites’ attacks on social mobility, and their ideal of a fixed social hierarchy, suggest that such an interpretation applies to them, particularly when these ideological features are set beside the marginal situation of many of the movement’s supporters.” Degas was precisely such a “marginal” figure in the social world of the late 19th century and had ample reason, by the decade of the ’90s, to be worried about his status.

Although it is asserted in most of the literature that Degas came from an aristocratic family, recent research has revealed that the Degas family fortune in fact had originated in rather shady adventurism less than 50 years before the birth of the artist. Degas’ grandfather, Rene-Hilaire Degas, made his money first as a professional speculator on the grain market during the Revolution, at a time when food shortages were provoking riots in Paris; then as a money changer, first in Paris, later in the Levant; and then as a banker and real estate operator in Naples. In other words, the Degas family moved up in the world by precisely the same questionable means Jews were accused of employing: speculation and money changing. Neither did Degas possess the “pure” French blood or the age-old roots in the French soil valorized by Drumont, Barres, and the ultranationalists. His paternal grandmother was an Italian, Aurora Freppa, and his mother, Celestine Musson, was a native of New Orleans, where her father was a wealthy and adventurous entrepreneur, whose main activity was cotton export, but who also speculated in Mexican silver mining. Although members of the Degas family in both Naples and in Paris began to sign themselves “de Gas” in the 1840s, thereby implying that they were entitled to the particule, that is, the preposition indicating a name derived from land holdings, and although one Paris relative even hired a genealogist to create a family tree legitimizing such pretensions, in point of fact, these forebears were, to borrow the words of Roy McMullen, “indulging in the foolish little parvenu trickery that was laughed at … as ‘spontaneous ennoblement.’” when Degas began signing himself “Degas” rather than “de Gas” after 1870, he was not rejecting an aristocratic background; he was simply signing his name as it really was. The parish register for the year 1770 that records the birth of Degas’ grandfather lists his great-grandfather as “Pierre Degast, boulanger.” Degas, far from being a scion of the aristocracy, was the descendant of a provincial baker, and the class into which he was born was in fact the grande bourgeoisie, a grande bourgeoisie of rather recent date and uncertain tenure haunted by memories of revolution and displacement. It was a family that moved a lot, even in Paris, during Degas’ childhood, rather than being rooted in a permanent family hôtel. By the time of Auguste Degas’ death in 1874, the Degas bank was near collapse; by 1876, it had failed; and two years later, the artist’s brother Rene, then living in New Orleans, reneged on his debt to the Paris bank, abandoned his blind wife and six children, and ran off with another woman. The family, in short, disintegrated, both morally and materially. Degas’ position at the time of the Dreyfus affair offers a classic example of the “status anxiety” associated with anti-Semitism. Not only had he chosen the marginal existence of an artist—and a nonconformist artist at that—but the family banking fortune had vanished; the family honor was besmirched, and the artist was obliged to sacrifice his comfortable private income to pay his brother’s debts. Degas, then, had come from a background as arriviste as that of any of the nouveau riche Jews his fellow anti-Semites vilified, but by 1898, even this recently acquired upper-class position was an insecure one, despite his success as an artist. Anti-Semitism served not only as a shield against threatening downward social mobility but as a mechanism of denial, firmly differentiating Degas’ fragile haut bourgeois status from that of the newly wealthy, recently cultivated upper-class Jews whose position was, to his chagrin, almost indistinguishable from his own.

What effect did Degas’ anti-Semitism have on his art? Little or none. With rare exceptions, one can no more read Degas’ political position out of his art, in the sense of pointing to specific signifiers of anti-Jewish feeling within it, than one can read a consistent anti-Semitism out of Pissarro’s use of stereotypically Jewish figures to personify capitalist greed and exploitation in the Turpitudes Sociales drawings. In Pissarro’s case, it was simply that no other visual signs worked so effectively and with such immediacy to signify capitalism as the hook nose and pot belly of the stereotypical Jew. There is, of course, always something repugnant about such representations, as there is always something suspect in representations in which women are used to signify vices like sin or lust, because in such representations there is inevitably a slippage between signifier and signified, and we tend to read the image as “all Jews are piggish capitalists” or “all women are seductive wantons” instead of reading it in a purely allegorical way.

The representation of anti-Semitism was a critical issue in the work of neither Pissarro nor Degas. In general, the subjects to which they devoted themselves did not involve the representation of Jews at all. By the time of the Dreyfus affair, Degas had more or less completely abandoned the contemporary themes that had marked his production from the late 1860s through the early 1880s, a period when, of all the Impressionists, he had been “mostly deeply involved in the representation of modern urban life,” to borrow the words of Theodore Reff.

There was, however, one sustained work of art by a vanguard artist at the time of the Dreyfus affair in which the question of anti-Semitism plays a central role, and that is the set of illustrations that Toulouse-Lautrec did for Clemenceau’s Au pied du Sinaï (1898), a series of vignettes of Jewish life. Although this is not the place for a detailed examination of Lautrec’s ambiguous position vis-à-vis Jews, anti-Semitism, and the Dreyfus affair—a subject well worth pursuing—certain aspects of his representation of Jews in these rather undistinguished lithographs are relevant to the present investigation. Once again, it is difficult to tell the artist’s position from the images alone, without knowing something of their context: how they are to be read; who is doing the reading; and at what moment in history the reading is taking place.

Clemenceau’s collection of stories and anecdotes is mainly about Eastern European Jews, not about educated French ones; it is related to the popular fin de siècle genre of the travel book. It tends to puzzle the few modern readers who bother to look at it, because it’s almost impossible to tell whether the book is meant as a sympathetic picture of specific Jewish types or a piece of anti-Semitic slander. Clemenceau, on some level, meant this as a plea for greater understanding of the Jews of Eastern Europe who were then being threatened with systematic persecution. In contrast to the racists of his time, Clemenceau insists on the racial diversity of the Jewish types he met in Carlsbad, where he went for the cure and with whose colony of Polish Orthodox Jews he is largely concerned. He insists nevertheless on one trait he deems common to all Jews, something he denominates “the subtle ray which seeks the weak point like the flash of a fine blade of steel.” Although he implies that the religious ceremonies of the Hasidim are bizarre, even grotesque, and consistently emphasizes the “sharp practices” of all Jews, rich and poor, his descriptions are in no way different from those of other travel writers of the time taking on the picturesque customs of exotic peoples. Readers familiar with the travel literature of the 19th and early 20th century devoted to the Near East or North Africa would find nothing surprising in Clemenceau’s descriptions of unwashed clothing or irrational behavior on the part of the “natives”; it is simply that this time the natives are Jewish. Modern Jews, not unreasonably, associate such discourses with those of anti-Semitism, rather than seeing them as one aspect of a wider phenomenon: the late 19th-century construction of the Other—Blacks, Indians, Arabs, the Irish—any relatively powerless group whose customs are different from those who control the discourse. Indeed, Clemenceau tries to redeem himself at the end of his section on the Hasidim with a plea for religious tolerance, asking whether it is “any more ridiculous to shake one’s head like a duck, than to do any other movements in honor of God?” He answers his own question by saying: “I do not think so. Christians and Jews are of the same human stock.” Lautrec provided some rather amorphous vignettes of Polish Jews with the sidelocks, beards, and prayer shawls exhaustively detailed by Clemenceau, but there is one lithograph in the series that stands out: the one titled “A La Synagogue,” for Clemenceau’s story, “Schlome the Fighter.” This story tells of a poor Jewish tailor who is drafted into the Russian army owing to the cowardice of his richer and more powerful co-religionists. He endures his years of conscription, returns to make his enemies pay for their betrayal, and then assumes his former humble role. It is the sort of David-and-Goliath fable beloved of Yiddish humorists like Sholem Aleichem, stories where the wily little Jew triumphs over more powerful adversaries in the end, except “Schlome the Fighter” is a story with a piquant irony at its heart, because it is the detested Russian army that is instrumental in strengthening the Jew in question, and it is his co-religionists, not the Russian oppressors, who are assigned the role of villains in the piece. Schlome the Fighter can take charge of his life—can become a folk hero, in fact—only when he becomes “un-Jewish” at the dramatic climax of the story; when his manly deed is done, he reverts to his previous state of impotence and humility.

Lautrec has chosen to illustrate the scene when Schlome forces the wealthy Jews gathered in the synagogue for the Day of Atonement to pay him a large indemnity. He represents Schlome exactly as Clemenceau describes him; with his prayer shawl flung over the shoulder of his uniform, he stands on the top step of the temple, the point of his saber against the floor, addressing the terrified crowd. It is a kind of witty, reversed ecce homo, where the persecuted figure actively confronts his tormentors, takes speech, and demands justice. Lautrec plays the forceful curve of his hero’s left arm and saber against the curve of the plume on his Cossack’s helmet; with his muscular legs and strong back appealingly revealed by his tight-fitting uniform, Schlome is a virile and eminently attractive figure. This is the only time that a Jew is represented as strong and sympathetic in the series—when the figure is totally unrecognizable as a Jew. We have to discover from the context, and the label, that this is a Jew not a Cossack; or rather that this is an anomaly: a Jewish Cossack. This is a token not so much of Lautrec’s personal anti-Semitism as it is of the fact that there was no visual language available with which he might have constructed an image at once identifiably Jewish and at the same time “positive” in terms that would be generally legible. The signifiers that indicated “Jewishness” in the late 19th century were too firmly locked into a system of negative connotations: Picturesqueness is the closest he could get to a relatively benign representation of Jews who look Jewish. As a result, the Pied du Sinaï illustrations make us uneasy. We don’t know quite how to take them: as anti-Semitic caricatures or as misguided but basically well-intentioned vignettes of life in an exotic foreign culture.

Degas, in his last years, when the storm of the Dreyfus affair had subsided, seems to have drawn back to some degree from overt anti-Semitism, although the evidence is equivocal. According to Thadée Natanson, publisher of La Revue Blanche, Degas’ voice trembled with emotion whenever he had to pronounce Pissarro’s name. Although he did not attend Pissarro’s funeral in 1903, he sent Lucien Pissarro his regrets, saying that he had been too ill to be present: “I was in bed Sunday, dear sir, and I could not go to take the last trip, with your poor father. For a long time we did not see each other, but what memories I have of our old comradeship.” Nevertheless, in another letter, probably referring to the recently deceased Pissarro, he talks about the embarrassment one felt, “in spite of oneself,” in his company and refers to his “terrible race”—hardly phrases he would have used if Pissarro’s Jewishness had ceased to be an issue. And while it is true that Degas paid a final visit to the Halévys’ house on the occasion of Ludovic’s death and continued to see the adoring Daniel for the rest of his life, he continued to cherish his anti-Dreyfusard opinions. “There are no signs,” according to his most recent biographer, Roy McMullen, “that he ever thought he had taken the wrong side in the great clash of the two Frances.” When his old friend Madame Ganderax complimented him in front of one of his paintings, saying “Bravo Degas! This is the Degas we love, not the Degas of the affair,” Degas, without blinking an eyelash, replied “Madame, it is the whole Degas who wishes to be loved.” He was implying, with a touch of bitter humor, that one could not love the artist without loving the anti-Dreyfusard as well.

This is of course not the case. One can separate the biography from the work, and Degas has made it easy for us by keeping, with rare exceptions, his politics—and his anti-Semitism—out of his art. Unless, of course, one decides it is impossible to look at his images in the same way once one knows about his politics, feeling that his anti-Semitism somehow pollutes his pictures, seeping into them in some ineffable way and changing their meaning, their very existence as signifying systems. But this would be to make the same ludicrous error Degas himself did when he maintained that he had only thought Pissarro’s “Peasants Planting Cabbage” an excellent painting before the Dreyfus affair; Degas at least had the good grace to laugh at his own lack of logic in that instance.

***

This article first appeared in The Dreyfus Affair: Art, Truth, and Justice, edited by Norman L. Kleeblatt for the University of California Press, 1987. It is reprinted here with permission of Julia Trotta.

Linda Nochlin (1931-2017) was an American art historian, Lila Acheson Wallace Professor Emerita of Modern Art at New York University Institute of Fine Arts, and writer.

Linda Nochlin (1931-2017) was an American art historian, Lila Acheson Wallace Professor Emerita of Modern Art at New York University Institute of Fine Arts, and writer.