The Dekrepitzer Blues

‘Come on Rebbe, play one of them nigguns’

You could hear the fiddle but couldn’t locate it as it echoed off the subway station walls. Abramson pushed through the crowds towards the IND tracks. There was a grey man with a full beard fiddling by the stairs to the Fifty-Ninth Street exit. It was 1965. Abramson was at Columbia studying the Hasidic music of Poland between the wars, particularly the fiddling of the Hasidic rebbes, the leaders of Hasidic sects who led their followers’ dances and songs. While there were references to the fiddling of rebbes, one of the only recordings was the set of tapes in the Cultural Archives Collection at the Library of Congress that Louis Fulder recorded in southeastern Poland in 1935. There was a fiddler leading a group of men in unusual songs— “Elyahu Oila B’esh” (Elijah Went up in Fire), “Kol Ha’Olam Yiraninu B’Lashon Echod” (All the World Will Rejoice in One Language), and the haunting “Atzmos Yehezkiel Yirkudu” (Ezekiel’s Bones Will Dance). The lyrics were unusual, but it was the fiddler who drew your attention. The playing was odd, but markedly better than the few surviving examples of fiddling by rebbes. The only identification on the tape was “The Dekrepitzer 23-8-35.”

Two years earlier, in a music ethnography course, Abramson had heard a 1947 field recording from Leesboro, Mississippi by the great collector Alan Lomax of an obscure Black blues group called the Brown Sugar Ramblers. Fiddling had become rare in blues recordings in the late 1940s. Pressed by the professor about the peculiar fiddling on the recording, a student who fiddled volunteered that it sounded like the fiddler was bowing with his left hand and, indeed, Lomax had remarked this oddity in his field notes.

That fiddler with the Brown Sugar Ramblers was unmistakably the fiddler on the Fulder tape, The Dekrepitzer 23-8-35. The same peculiar left-handed bowing sound and, after hours spent comparing them, Abramson recognized the same idiosyncratic phrasing. From the time he stumbled upon Fulder’s recording, Abramson puzzled how the same fiddler was on a recording of Hasidic fiddling in Poland in 1935 and a Black blues recording in rural Mississippi in 1947.

He studied what was known of the Dekrepitzer Hasidic movement. They had been a small sect in remote southeastern Poland. All its members were murdered in the Holocaust. They’d broken off from the large Dvillner sect in the mid-19th century in a dispute over Hebrew. The first Dekrepitzer Rebbe, Reb Yeruchem Moshe Lichtbencher, had a mystical vision of an imminent messianic age that would arrive when, as before the Tower of Babel, mankind spoke a common language. His mission was to spread that language, the holy tongue, Hebrew. He insisted that the Hasidim replace their Yiddish with Hebrew and drew a small coterie around him. He was tolerated as a crank until 1861, when his correspondence with Abraham Mapu, the author of the first modern novel in Hebrew, was discovered. Mapu’s book was considered a heretical desecration of the holy language. That same year, after Lichtbencher published Lashon Olamim, the Language of the Worlds, providing kabbalistic proofs of his vision, the Dvillner Rebbe had enough and issued a ban shunning him.

His small group of Hebrew-speaking followers eventually moved to Dekrepitz, then an abandoned hamlet in a wooded area in the Bieszczady mountains in southeastern Poland. Lichtbencher established his Hasidic “court” there in a worn shack. They observed the Hasidic rituals but spoke a Galician accented Hebrew of Eastern Poland, Glitzianer Hebrew, pronounced very differently from modern Hebrew. They only used Yiddish to communicate outside their community. Reb Yeruchem Moshe became known as the Dekrepitzer Rebbe, or, after his passing, as the “Alte Dekrepitzer.”

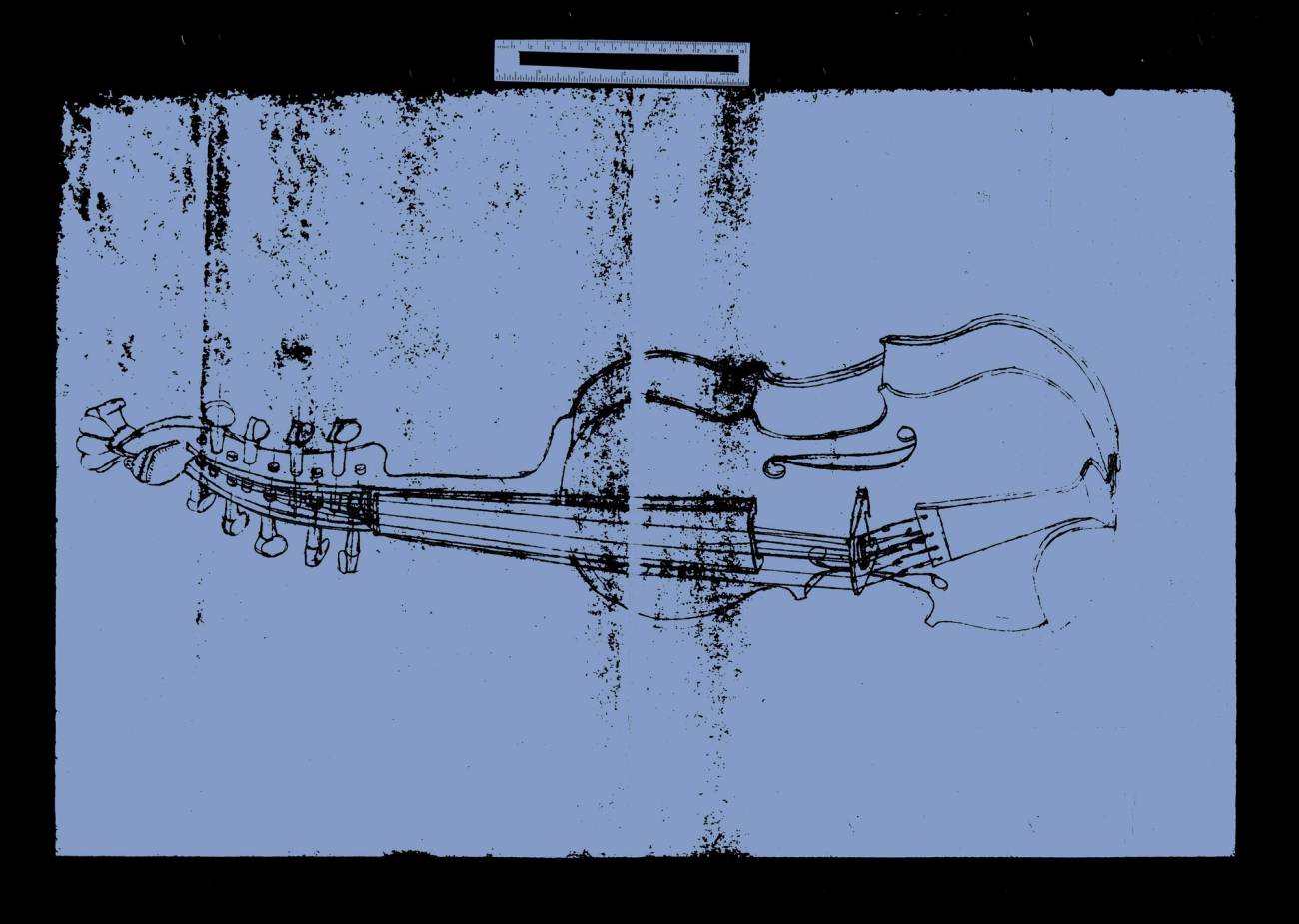

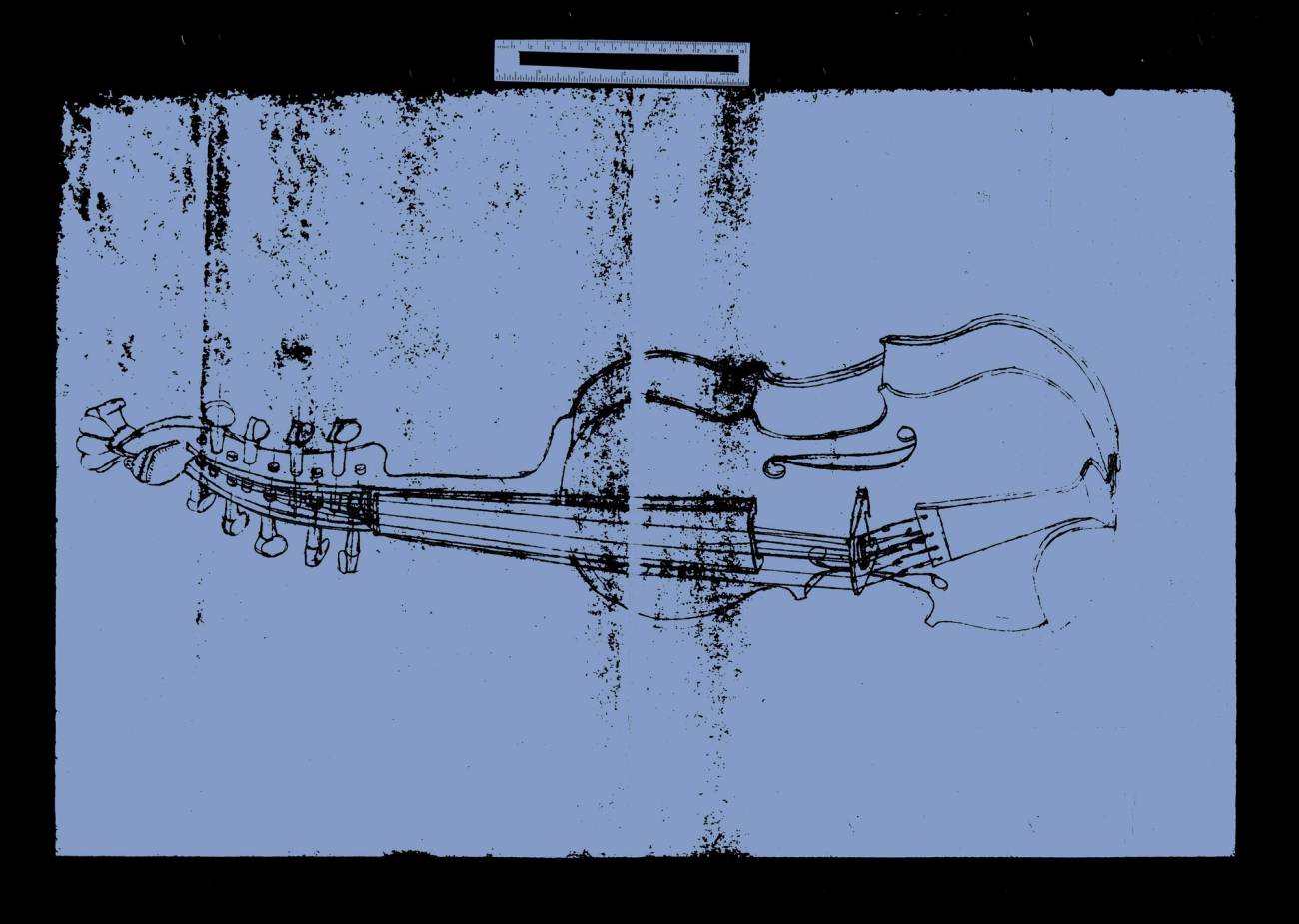

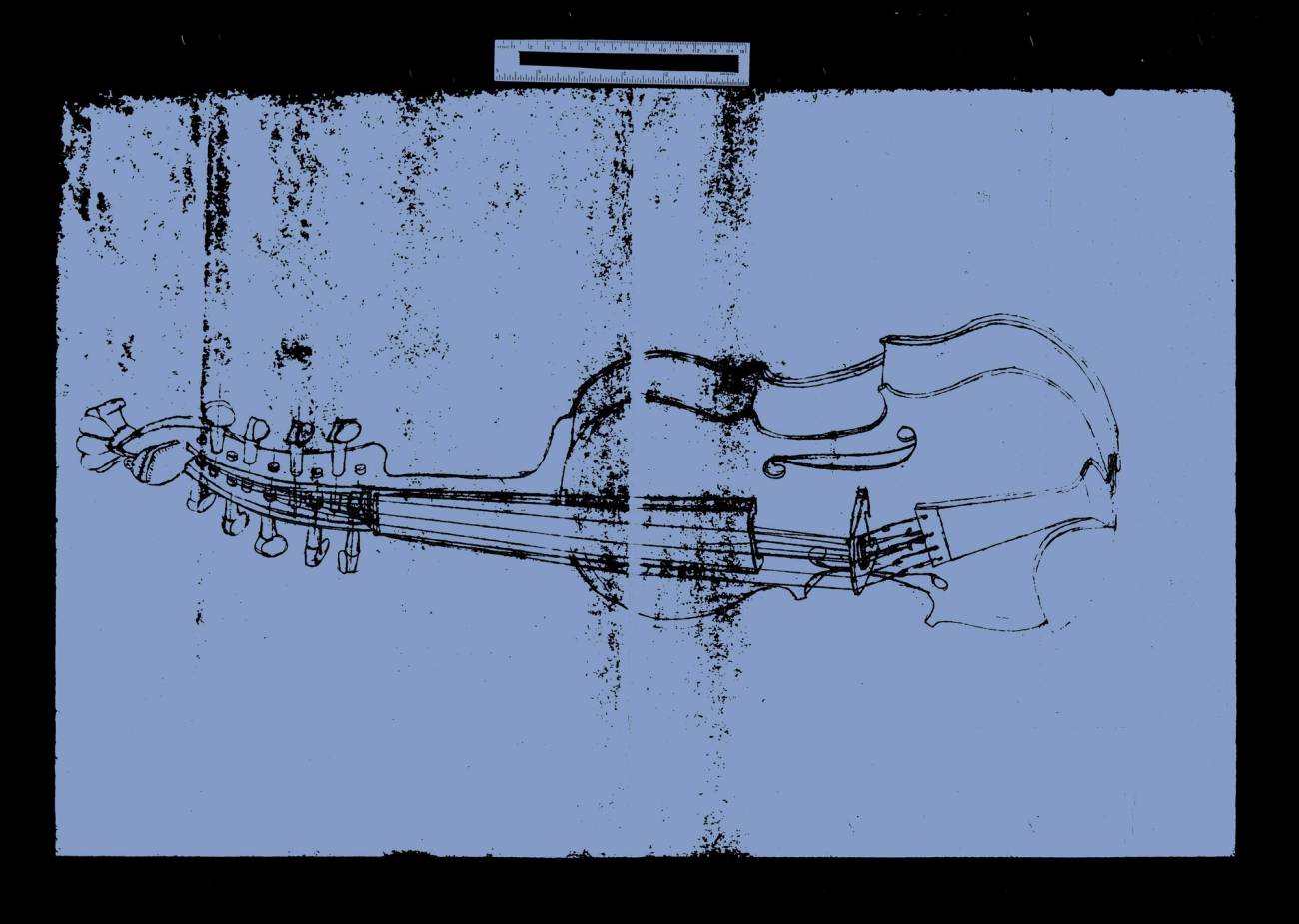

Aside from speaking Hebrew, the Dekrepitzers were known for their rebbes’ fiddling and songs, their niggunim. Other Hasidic rebbes fiddled, but Dekrepitzer rebbes were renowned for their fiddling.

Of the Brown Sugar Ramblers, Abramson could learn nothing. They seem to have been an evanescent group that came and went with just the trace found in the Lomax recording.

That was, until he saw the shabby grey man busking on the IND side of the Fifty-Ninth Street subway station. The man rested the fiddle on his right shoulder, fingered with his right hand and bowed with his left. It was the sound on Louis Fulder’s recording. Several trains went by and Abramson dropped singles in the violin case open on the ground so the man would keep playing. He was stocky with a full grey beard. Between the beard and his hat all you could see were his eyes and a sliver of forehead. When Abramson first heard him, he was playing blues and gospel, but when he realized the attention Abramson was giving, he played what sounded like Hasidic niggunim, finally one very much like, “Kol Haolam Yarananu B’Lashon Echod,” on the Fulder tape. Abramson put another dollar in his case and said “Atzmos Yehezkiel Yirkudu.” The man stopped abruptly. He stepped towards him and by his look, Abramson thought he was going to grab and hug him. But the man hesitated. He bent over and gathered up the coins and bills from the case before putting in the fiddle.

The man motioned for Abramson to follow him. They left the station and Abramson followed the man across Columbus Circle into Central Park. He sat down on a bench, rested the violin case beside him and motioned for Abramson to sit down.

“You’re the son of a Dekrepitzer, aren’t you?” he said.

“No. No Hasidic blood at all,” said Abramson. The man was silent and obviously surprised. Then he buried his head in hands. He said nothing for a few minutes until Abramson put a hand on his shoulder and the man lifted his head.

“How’d you figure out who I am?” He sounded like a Black man with the accent of a Polish Jewish refugee. “You seem to know I’m the Dekrepitzer. How you know that?”

“The left-handed bowing, the niggun.”

The man stared at the pigeons. “How you know about the fiddling and niggunim? Ain’t no Dekrepitzers since the war.”

Abramson told him he was studying the fiddling of Hasidic rebbes. This broke the tension. The man started laughing so hard that Abramson thought he would pass out. Every time he looked at him, the man burst out again. When he composed himself, he said, “The rebbes were the worst fiddlers ever, the rebbes. There were Hasidim that could fiddle,” he used the Hebrew plural of Hasid, “but the rebbes, they was the worst.”

“The Hasidim didn’t seem to think so.”

“Everybody was fronting like the rebbes were wonderful, just because they was the rebbes.”

“And you played with the Brown Sugar Ramblers.”

“Man, that was a long time ago.”

“I heard the recording by Alan Lomax.”

“So how you know about the Dekrepitzer fiddling?”

“There’s the recording by a man named Fulder. It says it was recorded in Dekrepitz in 1935.”

“That’s me and the Rebbe playing, my zeida, my granddaddy done taught me.”

“So are you the Dekrepitzer Rebbe?” Abramson couldn’t believe it.

“Since the war, ain’t no Dekrepitzers, but I am the Dekrepitzer. Ain’t got no choice. I’ve been the Dekrepitzer since my daddy and zeida got murdered with all Dekrepitz. I’m the Dekrepitzer nister—hidden. Best to stay that way”

“Rebbe, you are Reb Shmuel Meir Lichtbencher?”

“Nobody done called me that in a long time. People call me Sam Lightup.”

“Rebbe, to me you must be the Rebbe.”

“I thought you were a Dekrepitzer. I been playing Dekrepitzer niggunim in the subways for years—West Side, Brooklyn, where the Jews be. Hoping maybe there’d be some Dekrepitzer who recognize the niggunim. Then here comes you, no Dekrepitzer but you recognize the niggunim. …” His voice tapered off. “I’m the Rebbe, but I ain’t your rebbe.”

He was not Abramson’s rebbe.

When the war started, Dekrepitz was so remote that people didn’t take much notice. The Germans and the Russians had partitioned Poland and Dekrepitz first learned one day in the winter of 1941 that it was in the Russian sector. After returning from the yeshiva in Baranowicz, Shmuel Meir had continued studies with his grandfather. As things got worse, the Rebbe was distracted. People came to him at all hours. Shmuel Meir left his studies and spent his time assisting with the chickens and cows.

In February 1941, a motor car managed to come up the long wagon trail to Dekreptiz. It had never happened before. Most of the people in Dekrepitz had never seen a motor car. It had a big red star on the side and looked official. It carried a Russian officer and two armed soldiers.

The soldiers shouted in Russian. Nobody except Shmuel Meir spoke anything but Yiddish and Hebrew. Shmuel Meir had learned some Polish in his years at yeshiva in Baranowicz. He understood that the soldiers wanted to see the mayor. The closest thing to a mayor was the Rebbe. Shmuel Meir led the officer to the Rebbe’s house. The officer entered alone, shut the door and, in perfect Yiddish, asked the Rebbe to start speaking to Shmuel Meir in Hebrew. Everyone was dumbfounded. There was silence. “Nu!” the officer shouted. The Rebbe told Shmuel Meir in his Glitzianer Hebrew to ask the officer if he wanted something to drink. The officer nodded—not that he wanted something to drink—but impressed. He told the Rebbe to take out his fiddle and play some niggunim. The Rebbe’s hands were shaking. Shmuel Meir doubted he’d get out a note, but he played, “Atzmos Yechezkel Yirkedu,” Ezekiel’s Bones Will Dance.

When the Rebbe finished, the officer shook his head and whistled under his breath. He was a big man about forty. He said he’d heard about Dekrepitzer fiddling but never believed it. He had to see it. The Rebbe asked where he’d heard about it. “Slabodka” the officer said. Shmuel Meir and the Rebbe looked at each other. The officer had studied at the great Slobodka yeshiva. Word was the yeshiva had been filled with Communists.

“Who else fiddles?” He asked. He looked at Shmuel Meir and ordered him to play. While he played, the officer kept shaking his head. When he finished, the officer said to the Rebbe, “We’re sending him to the conservatory in Moscow. We’re taking him with us.” He said that he’d learn to fiddle right and be great or he’d become a folk showpiece with his backwards fiddling. He’d heard rebbes fiddle and it had been an embarrassment to him, the worst playing imaginable. He’d heard about Dekrepitzers, now he saw and heard it. It was all they said it was and he was going to see that it was properly developed.

Shmuel Meir protested that he had a wife and child. The officer told him that he could send for them when he was settled in Moscow. His grandfather took him aside and blessed him. He found his father by the orchard and they hugged goodbye. His mother was with his wife and the baby. His wife couldn’t understand what was happening. Shmuel Meir kissed her on each cheek, but she didn’t respond. His mother held up the baby and he kissed it. They were off in an hour. That was the last he saw of his family. A week later he was in Moscow. On June 21, 1941 the Nazis invaded Russia.

“Eventually, I ended up in Naples in 1945,” said the Rebbe, the Dekrepitzer nister, Shmuel Meir. “It was bad. The Italians had nothing. Desperate people. American soldiers screwing the Italian ladies. First time I seen a colored man was an American soldier. I stared so I scared the daylights out of him. Never seen a Black man before. He reach into his shirt pocket and gave me a chocolate bar. Another thing I ain’t never seen before. Had to unwrap it and show me how to eat it.”

That was how he met Willie Carr. He hung after him as the Black soldier walked on after giving him the chocolate bar. They ended up by the wharfs where other Black soldiers were playing together, a fiddle, a harmonica and a guitar. Shmuel Meir had never heard music like they were playing. When they stopped, he surprised the soldiers by pulling the Dekrepitzer fiddle from the pack on his back. When he ran the bow across the strings in his left-handed way the soldiers began to laugh. But when he began adjusting the tuning pegs they stopped laughing and watched as he tuned and began playing with the fiddle in his right hand. He played a Dekrepitzer niggun. He hadn’t played in a long time and was soon lost in his thoughts of the wandering that had brought him to this city by the sea. He’d never seen the sea before nor the big ships that lined the wharfs. He played as though his playing were a prayer, though he didn’t know what remained to pray for. He played a niggun he recalled his grandfather playing after his morning prayers. The soldiers spoke animatedly among themselves. Though Shmuel Meir didn’t understand English, their talk recalled him to where he was. They motioned for him to play with them, but he’d never played with others. They finally motioned for him to start playing and they slowly joined in with his niggunim.

The soldiers were waiting to ship home. They’d been through the war. They’d seen awful things and word had gotten around about much worse. They realized the fiddler wasn’t Italian and was probably a Jew who survived. Each day the Black soldiers would play together by the American ships. Shmuel Meir took to playing with them. Having only fiddled by himself, he was fascinated by harmony and chords. With no common language they signed to each other.

One day, they hustled him behind a building by the docks. They pulled out an American Army uniform and motioned for him to put it on. They hung dog tags on him that had been left by a soldier who’d run off with an Italian girl. Willie Carr put his finger over his mouth motioning for him to keep quiet. “Nein, git it? Nein. No speak, no speak.” He then threw his hands in the air and threw back his head a few times and repeated the talking motion with his hands while shaking his head and then putting his finger in front of his mouth. Shmuel Meir understood. He was to pretend he was shocked into silence. They smuggled him on board the troop ship. They were Willie Carr, Bill Jones, and Horace Quarrels. Before the war they’d played together as the Brown Sugar Ramblers.

Below deck, among the Black sailors, they played the blues and played cards. Left by themselves, they played the blues for hours on end. Shmuel Meir began learning English as each line was sung over and over. His new friends amused themselves teaching him raunchy lyrics. He didn’t know what they meant but could sing them. When he thought he’d sensed their meaning he’d have his doubts when his friends broke up laughing at his singing:

Keep on truckin’ baby, truckin’ my blues away, yeah

Keep on truckin’ baby, truckin’ my blues away

I know a gal she’s long and tall

When she starts to truckin’ make a little man squall

Keep on truckin’ mama, truckin’ my blues away

I mean, truckin’ my blues away, yeah.

The Rebbe was embarrassed years later, but laughed when he sang them. He knew lots of them:

Hot tamales and they’re red hot, yes she got’em for sale

I got a girl, say she long and tall

She sleeps in the kitchen with her feets in the hall

Hot tamales and they’re red hot, yes she got’em for sale, I mean

Yes, she got’em for sale, yeah.

More often, they sang gospel. He had little better idea what he was singing, but there was no laughing:

On my lonesome journey, I want to be saved

On my lonesome journey, I want to be saved

Saved from the way I walk in

Saved from the way I talk in

Oh, my Lord I want to be saved

When my enemies around me, I want to be saved

When my enemies around me, I want to be saved

Saved from the way I walk in

Saved from the way I talk in

Oh, my Lord I want to be saved

Understanding came later. Meanwhile, the Black soldiers began teaching him what he came to call his blues English.

When they docked he had nothing but his army uniform and fiddle. Willie Carr took Shmuel Meir home with him to Leesboro, deep in the Mississippi Delta. Leesboro was just a store, a clapboard church and a few houses. People lived in the surrounding woods. Carr’s arrival home with the dirty white soldier was awkward. Willie’s mother couldn’t stop hugging him. His father wanted to hug Willie but had to stop over and over to control his coughing before he finally hugged him. He stared at Shmuel Meir and eventually put out his hand. When he realized Shmuel Meir was staying, he didn’t seem happy about putting up a white man who barely spoke any English.

Willie’s father, Harold, had seen chases and beatings. He’d seen mothers after lynchings. But he hadn’t seen what Willie had seen and Willie didn’t want to share what he’d seen with his father. Over the first week, the old man continued to seem hostile to Shmuel Meir. He’d never seen a Jew, only heard about them, and wondered at his harboring one.

After a week of this, Willie told his father what he’d seen and offered his guess as to what the man he brought home had been through. Harold didn’t want to believe his son had seen such things but they were too terrible for him to have made up. He kept to himself, less hostile, but very disturbed. A couple of days later Willie said, “Rabbi, bust out that fiddle for my daddy and show him what you can do.” Shmuel Meir fetched the fiddle and began “I Want to Be Saved.” Harold was torn between the poignancy of the song and the comedy of the man’s weird accent and left-handed bowing. He began laughing until he was overcome coughing. Willie shouted, “Come on Rabbi, play one of them nigguns.” Willie joined him with his harmonica. The old man shook his head. Later he asked Shmuel Meir, “You a rabbi or do Willie just call you that?” “Can’t say.” Shmuel Meir said. “Willie call me what he want.”

After that Harold built a lean-to on to their shack for “the Rabbi” to sleep in. That’s what they came to call him. Nobody knew what to do with him. They’d some idea that he’d been through things they’d rather not imagine. So they were warm but kept a wary distance.

This story is excerpted from the forthcoming novel “The Last Dekrepitzer” by Howard Langer, to be published early next year.

Howard Langer is an author and lawyer living in Philadelphia. His early stories and translations have appeared in Promethian and Shdemot.