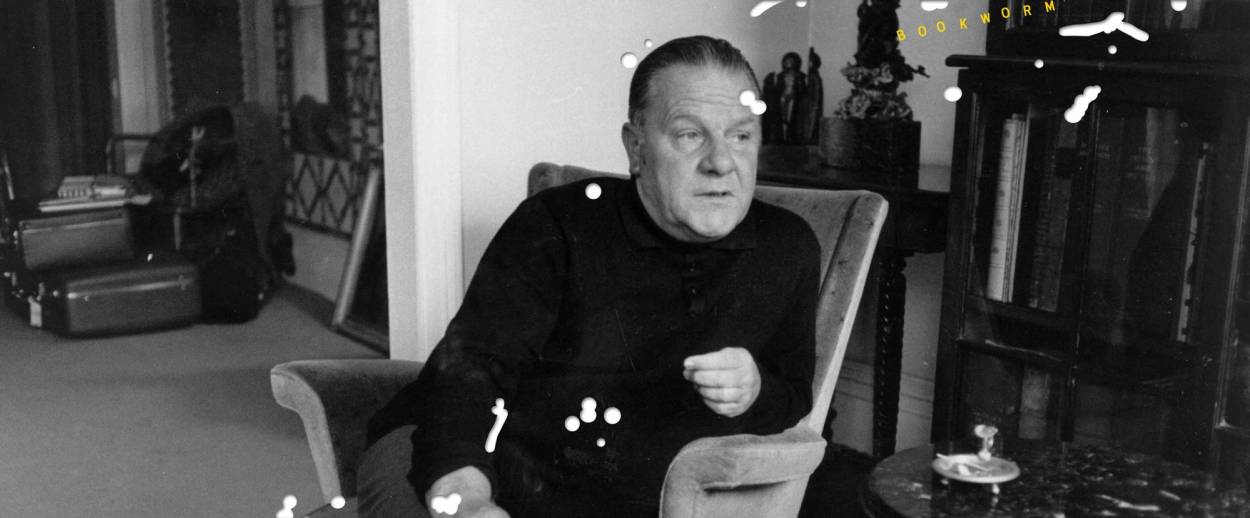

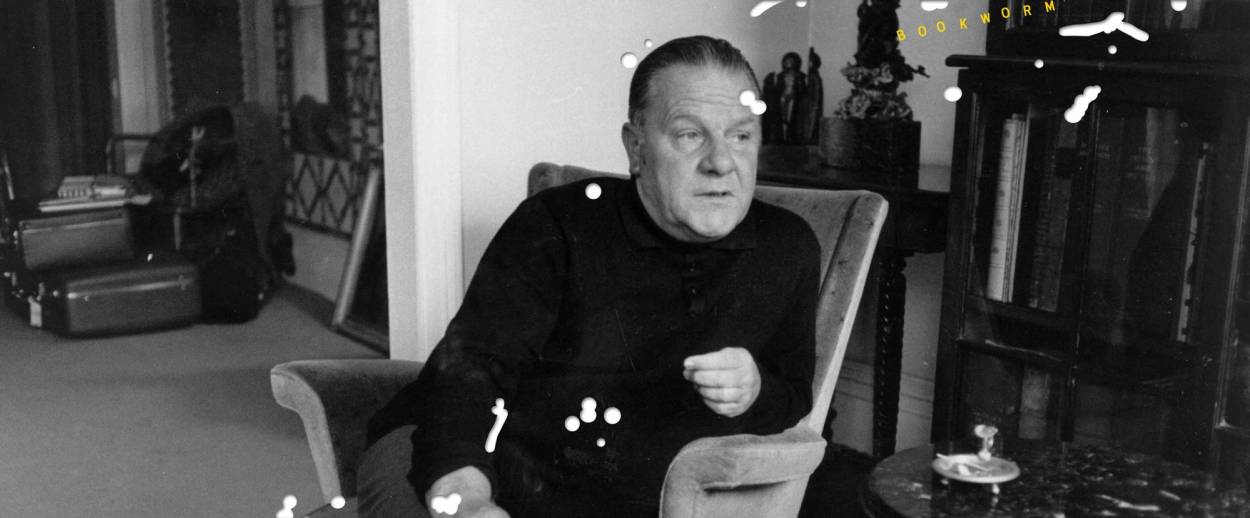

The Stunning, Delicious Depravity of Lawrence Durrell’s ‘Justine’

‘Bookworm,’ Tablet’s voracious new column: Alexandria swoons

I am going to steal this sentence.

This is my first thought after reading the opening line to Lawrence Durrell’s Justine, the first installment of the author’s Alexandria Quartet. “The sea is high again today, with a thrilling flush of wind.” Two pages later I have a similar thought, and I make a slight tear in the middle of the page then fold over the paper, a signal to some future version of myself: Here is where we can learn a lesson.

By the time I finish the first chapter, I am devastated. I realize that one of my greatest flaws as a writer—one of my greatest failures—will be that I had not written Justine. Worse, I will never be able to produce something like Justine.

Justine is the story of a floundering writer juggling two love affairs and teaching English in his spare time to the wealthy Egyptians in Alexandria. He meets Justine, the Jewish wife of a wealthy Egyptian businessman who, from time to time, finds her way into the beds of strange men.

Reading this love story that takes place in a still-colonial Alexandria is somewhat disorienting for me—an experience not dissimilar to reading the most intimate letters of a grandparent whose stories you know too well but who also passed away long before you were ever born. Alexandria is the city where my father was born—the setting not only of his most exciting childhood stories but of his memoir Out of Egypt.

I have never visited Alexandria. When Durrell’s narrator walks through the Corniche of Alexandria—a long, thin dissolving strip of sidewalk beside the sea of which I have seen only a few photos—I know it only as the street where my grandfather, in the late stages of dementia, asked me to take him for a walk one afternoon in the spring of 2008 while living in New York. But it doesn’t take long, however, for Durrell’s Alexandria to feel like an entirely different city from the one I sort-of know. In the late afternoon sun above the Mediterranean, I hear the nasal tones of Damascus love songs, the flesh and blood and death screams spilling out of a nearby abattoir, and wonder if something so vile has ever seemed so beautiful.

Beyond Durrell’s stunning prose, there is a sinister sensuality that wounds a reader as suddenly and as unforgivingly as it does the narrator, the tale of broken and misguided love affairs, a fleet of disconsolate hearts and characters as shamelessly deceitful as the narrator is honest. In Justine, lies are simply ways of communicating a difficult truth. Justine makes us yearn for the sort of wealth we can get only from the love of another person, from loving someone more than they want us to but just as uninhibitedly and savagely as they demand. Justine is a book that teaches you what it means to be a great writer. It is is a book that shows you how little you know, how rich, how extravagant the world is, how little of it you have seen, and exactly how much you have failed to describe it.

Durrell’s single large failure in this book was his attempt to turn Alexandria itself into a character—a city whose spirit imbues every person with a sort of mystery, a shadow that compels us to abandon all affectation and become savage. But it is sex, not a physical location, that does this to us. Durrell tries half-heartedly at times to get this idea across, scattering lines throughout the book on how Alexandria was the source material for all this, as if in response to some theme-seeking editor’s note. Yet Alexandria is, aside from the stunning descriptions, largely immaterial to the plot. I am not at all convinced that Durrell couldn’t have strung together descriptions as halting and as heartbreakingly perfect about Tallahassee or Jersey City.

But this conceit is easy enough to forgive because of the breathtaking skill and insight with which Durrell lays bare the hearts of his Alexandrians. With this novel, which has so few lines of dialogue, which takes place almost entirely in the cutting metronome pitter-patter of a broken writer’s mind, a reader sees bordellos, Italian specialty shops, low-hanging clouds of hashish, the bed of his live-in girlfriend—a fragile prostitute whose work seems to bother him not at all and very, very deeply at the same time—the long strand of the corniche, shady cabanas where two people who shouldn’t be together somehow end up, their skin coming closer and closer together. You read Justine and then walk to your window on 109th and Columbus and can only think: The sea is high again today, with a thrilling flush of wind. The sea is high again today, with a thrilling flush of wind.

***

Read Alexander Aciman’s Bookworm column in Tablet magazine on Mondays.

Alexander Aciman is a writer living in New York. His work has appeared in, among other publications, The New York Times, Vox, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic.