Before the ascendance of photography and television, Abram Games‘ posters helped define an era of advertising and propaganda. He catapulted the high-speed airbrush to popularity among graphic designers, and his streamlined draftsmanship—marshaled on behalf of everything from Guinness beer to knitting to displaced-persons camps—created a spare language both vivid and evocative.

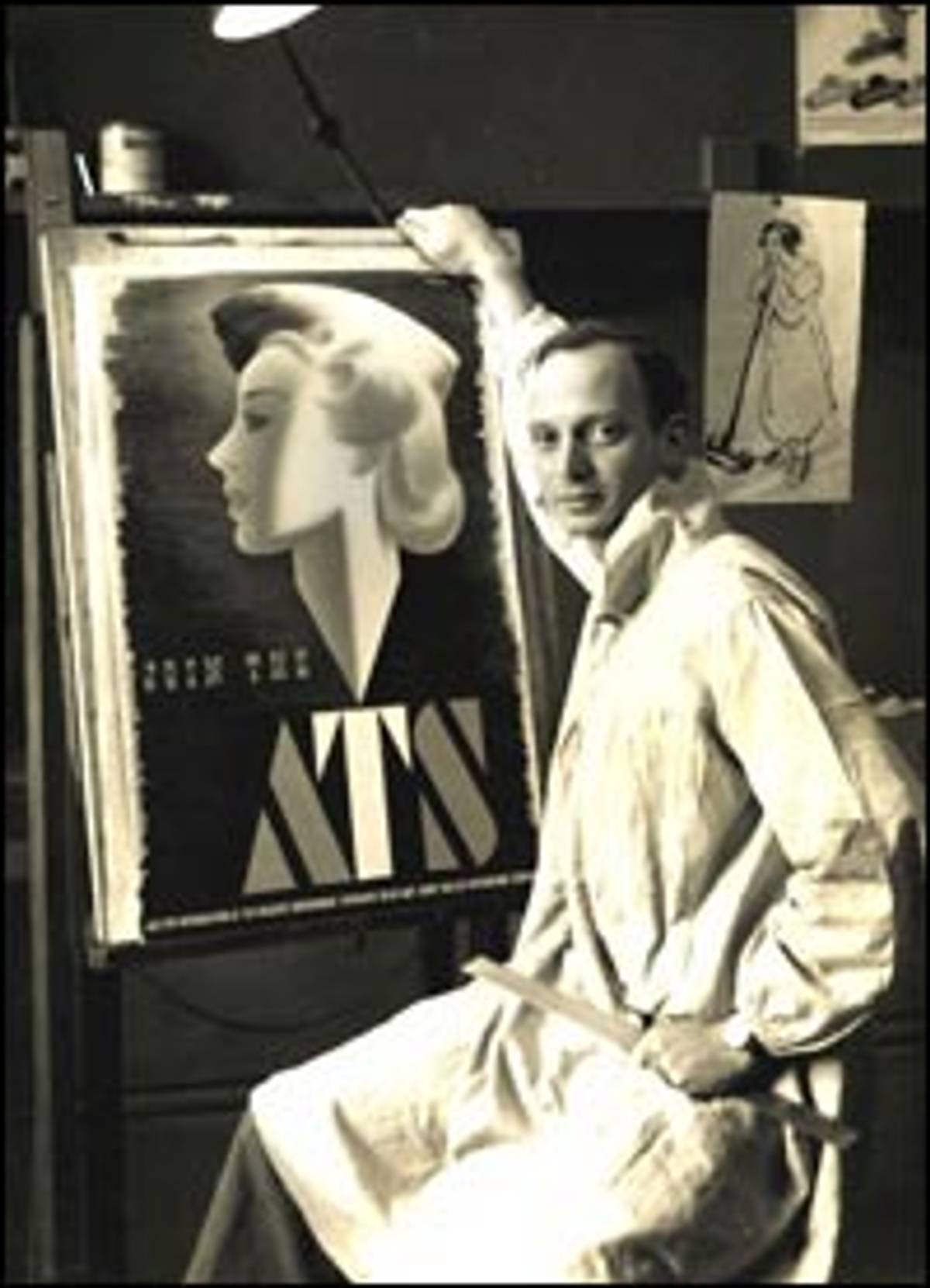

Born Abram Gamse in 1914 in Whitechapel, East London, the son of Eastern European immigrants, Games studied briefly at the St. Martin’s School of Art but left to follow his own creative path. He drew inspiration from graphic artists such as El Lissitzky, Edward McKnight Kauffer, A. M. Cassandre, who worked independently and applied simple designs using unexpected forms. Games first gained widespread recognition in 1936, when he won a competition conducted by the London County Council for a poster encouraging people to take evening classes, and was soon at work on projects for Shell, Guinness, London Transport, and the BBC. However, it was as Official War Artist—a position created for Games—that he left an indelible mark, designing more than 100 wartime posters and creating the visual language of British domestic propaganda.

Working in the shadow of World War II, the Holocaust, and fascism, Games worried about the ethical responsibilities of graphic designers. His concerns led him to develop an ethics of form, which he saw as a designer’s responsibility to provide “maximum meaning” with “minimum means,” and also an ethics of content; a designer, he wrote in 1951, must be “convinced that what he is doing is right, not only for himself but for his fellow men.” Games often worked pro bono for causes in which he believed—he created posters for agencies resettling liberated European Jews in Palestine, and postage stamps for Israel’s young Philatelic Department. Although Games, who died in 1996, never identified himself this way, it is possible to think of him as a designer for a nation, first helping to craft the vision and voice of mid-century Britain and then the emerging state of Israel.