Divided Families on Film

The family dynamics in World War II-era movies make today’s political disagreements seem like sandbox squabbles

If you think the times we’re living in now are perilous and dark—they are not, I believe—and that people are divided, especially within their families and among spouses and friends, we should take a look at film history. Films made in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s—before, during, and in the aftermath of World War II—explore the abyss that opens wide between family members, even husband and wife, due to different viewpoints on current events, or because of ideology and ambition. This overview of some of these films from both sides of the conflict may make you feel better about whatever disagreements you recently had at the Zoom Seder.

The Man I Married (1940)

Set in 1938 after the Austrian Anschluss (annexation), The Man I Married features Francis Lederer as Eric Hoffman, a German-born and German-raised resident of New York who is married to an American. He and his wife, Carol, an art critic for a magazine (Joan Bennett), have decided to travel with their 7-year-old son Ricky to Hoffman’s birthplace in Germany to help Eric’s father (Otto Kruger) to dispose of the factory the family owns in Berlin. Upon their arrival, Eric’s father tells his son that the old Germany is gone. But Eric doesn’t care. He loves the transformation he has witnessed all around him and is mightily proud of his country and his Germanness. He falls under the influence of Frieda, his father’s secretary and a former schoolmate of his (Anna Sten), an enthusiastic Nazi, prim and proper and determined to lure Eric away from his American wife. He doesn’t need much luring. Carol at first tries to fight for her husband but resigns with disgust when it becomes obvious he slept with Frieda. He demands a divorce from Carol and declares that he will keep their son to grow up in the new Germany. Carol is horrified. The German authorities are certainly on his side. Carol must find a way to leave the country together with Ricky.

Lederer’s portrayal of the subtle, slow, but certain transformation of a German American into a Nazi is a masterpiece. (The actor was an émigré to America from the small enclave of German-speaking Prague Jews that included Ernst Deutsch, Kafka, and Franz Werfel, among others.) He reveals the ultimate vainglory of a man finding his roots and proclaiming them loudly in the hope he can join the new “master race”: the quiet metamorphosis of a mild-mannered husband into a human monster—who is proud of it.

Address Unknown (1944)

James Agee was off-key when he called Address Unknown “vapid anti-fascism” in a contemporary review. Photographed by Rudolph Maté, it stars Paul Lukas as Martin Schulz, a San Francisco art dealer in a partnership with his good friend Max Eisenstein, a Jew, played by Morris Carnovsky. They both hail from Munich. Martin Schulz leaves America with his four young boys and wife (the Austrian émigré Mady Christians) to return to Munich, leaving his son Heinrich (played by Peter van Eyck) with Max in San Francisco. Heinrich and Griselle, Max’s daughter (K.T. Stevens), were to be married but they have agreed she would go to Germany for a year to see whether she could launch her career on the famed German-speaking stage.

Schulz is a man of weak character; he hungers for power and influence and is apparently willing to do what is necessary and what is asked of him, without qualms, in his readopted country. Germany has new rulers and new rules. The power broker Baron von Friesche (played by Carl Esmond, another émigré Hollywood actor) gets him a job as a high bureaucrat in the Ministry of Culture.

Meanwhile, Griselle goes on stage in Berlin. She is nearly arrested for saying some forbidden lines during a performance and must escape. She gets to the estate of her “uncle” Martin Schulz while being pursued by SA storm troopers. Martin shuts the door in her face. She is killed.

Martin writes to Max in San Francisco to inform him of the death of his daughter. Heinrich, who is present when Max receives the letter, is silent. At first he wants to comfort Max, who is seen crushed with hunched shoulders, but then Heinrich balls his fist: silent but boiling inside.

Martin starts receiving cryptic letters that appear to relate to art dealing but are transparently coded, although the code is unknown. The letters are opened by the Nazi censors. The letters keep coming. The baron warns Martin. The repeating scene of the mailman on a bike leaving a letter in his mailbox at the front gate and then ringing the bell is like a death knell for the suspected traitor. Schulz is desperate to stop the letters. Martin is fired from his job at the ministry. He is definitely under suspicion.

Alone in his house, the bell rings to announce the arrival of new letters. The interior is like an elegant cage for the frightened and increasingly frantic Martin, with its lone lit window, the leaves blowing across its shadowed court, its interior checkered black and white. Martin is in a web of his own ruined ambition, in a snare caused by his own ruthlessness and immorality, his failure in remaining humane. Now he is contemptible.

Who has sent the letters to Martin Schulz?

At the end, we are back in San Francisco at Max Eisenstein’s gallery. Max receives a letter with the stamp “Address Unknown” across the recipient’s destination in Germany. He tells Heinrich, whose face and shoulders are framed on both sides by two shafts of black darkness in what is apparently the rear of the gallery, “I don’t understand. I didn’t send Martin this letter. Why, I haven’t written him since …” Max looks at the returned and unopened letter and then looks again at Heinrich; it dawns on him what has happened. We see the horror on his face.

Hitler Youth Quex (1933)

In the Reich, Hollywood’s bad guys were often the good guys. Hitlerjunge Quex (Hitler Youth Quex) featured a teenage Nazi named Heini Völker who fights with his father, a lifelong communist (Heinrich George), to let him join and participate in the Hitler Youth. As depicted in the film, the Hitler Youth did have more fun than the communist youth. Besides that, they wore snazzy uniforms and waved flags. But father Völker definitely did not approve—until the father is convinced by brigade leader Kass (Claus Clausen) to recognize where his true loyalties lay: with his volk, not with his working-class comrades and corrupt communist leaders.

S.A.-Mann Brand (1933)

This bit of salacious propaganda is the story of a heroic Nazi storm trooper who defies the communists in his working-class neighborhood as well as his committed Social Democrat father (Otto Wernicke) to organize a Nazi propaganda march, which his father finally joins at the end. The picture ends with the very first use in film of the Horst Wessel song that starts with the words: “Raise the flag ...”

Chin Up, Johannes! (1941)

Kopf Hoch, Johannes! was produced by Viktor de Kowa. It starred Douglas Sirk’s estranged son Klaus Detlef Sierck. Sirk had divorced his then wife, the actress Lydia Brincken; his son was left to grow up with his mother, who became a convinced Nazi in the early 1930s. Sirk himself left Germany in 1937 for Hollywood after directing some films in Nazi Germany. The boy had gotten into the acting business by then. He became a youth star. Chin Up, Johannes! took place in a so-called Napola school (a Nazi boarding school for young leadership talent), involving a wayward adolescent (Sierck) who refuses to buckle down to school and comradely discipline. He’s a rebel. But that was also OK, according to the film, because he was talented (he composed marches) and his heart was in the right place (with the Fuehrer).

Young Johannes doesn’t get along with his strict father, doesn’t like the school he’s been stuck in, and is generally a nuisance, albeit a talented young man. Johannes ultimately finds his way to become an exemplary young Nazi. The young actor who played him, Klaus Detlef Sierck, had a harder way, though. He fell into disrepute with Goebbels the following year. Goebbels suspected him of being homosexual. The young man, by 1942 all of 17 years old, enlisted in the Wehrmacht and died fighting in 1944. His father searched for him after the war ended when Sirk returned to visit Berlin. The boy’s grave was in Ukraine. Sirk had not known what had happened to him.

And the Heavens Above Us (1947)

Und über uns der Himmel, with Hans Albers in the starring role, directed by Josef von Báky, is, at first glance, about the functioning of the black market in Berlin before the introduction of the German mark and the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany, in 1948 and 1949, respectively. Hans Albers plays Hans Richter, who has lived through the Third Reich and the war years and is quite happy to be rid of both; he makes a living on the black market. His son Werner has returned blind from the war. Hans the father must continue selling on the black market because he needs money to pay for medicine and medical care for his son. He gets the money, and his son’s eyesight is restored. Now the young man sees what his father is doing, resents his activity, and tells his father to his face that he is not happy. At first, the elder Richter is in disbelief that his son is moralizing about the black market; at the beginning of the film, the older man says he is so glad to be alive in the city without the “boom-boom” of bombs dropping on the city’s collective head, happy to be safe and sound now that the war is over. And the young Werner now sounds as morally pure as a Nazi, chiefly because the young people like him only know the “morality” of the Nazis—the same claptrap phrases that the party had been preaching to the German people for 12 years. So as a reward for his sacrifice and effort to scrape up the money to pay for his son’s medicine and a cure, the father hears his son’s reproaches about “morality.”

The Last Illusion (1949)

Der Ruf, again directed by Josef von Báky, starring Fritz Kortner, takes place initially in America, then follows its protagonist to a German university town. Kortner also wrote the screenplay. As the film opens, The Last Illusion features a depiction of a one-of-a-kind artistic and intellectual community that had found its home in the city on the West Coast in the 1940s, the exiled Germany in Los Angeles, a once vibrant émigré subculture. Kortner plays professor Mauthner, an exiled professor of philosophy, a Jew, who is called back to teach at a famous German university. The Last Illusion presents an effective and wholly doomed portrait of postwar German students and academia in the small university city. Mauthner tries to reconnect there with his ex-wife (Johanna Hofer, Kortner’s real-life wife).

But the reconciliation doesn’t work. Mauthner is still bitter about her family and the antisemitism he experienced with certain members of her clan; she is bitter over him and his headstrong and proud behavior. She had obviously stayed behind in Germany. One young man is particularly vehement in protesting Mauthner’s lectures on Plato and the ideals of philosophy. We learn at the end that this young man is actually the professor’s son. The young man himself was unaware of it; his mother had kept it from him during the Nazi years. He attempts at the end to make amends, but it is too late. The rift remains; the chasm does not seem mendable.

The Big Lift (1950)

Montgomery Clift plays Tech Sergeant Danny MacCullough, the flight engineer for a C-54 Skymaster, with Paul Douglas as Master Sergeant Hank Kowalski. They are part of the crew delivering vital supplies to the Berlin population during the Berlin Airlift in 1948-1949. Kowalski had been a prisoner of war in Germany during the war. He hates the Germans and does what he can to be rude to them, doesn’t trust them. He is dismissive of Danny MacCullough’s empathy with and interest in them.

Danny meets the pretty Berlin widow Frederica Burkhardt (Cornell Borchers), who speaks English. Danny gets very involved with Frederica, a German dame whose number Hank thinks he has—Hank doesn’t like her at all.

Frederica tells the two Americans her father was a professor at Berlin University and active in the resistance against Hitler. She also says her husband was killed in the war; he had been a conscripted soldier, implying he was no Nazi since Frederica also ironically asked whether there was conscription in America too. Afterward, Hank does research—at the Berlin Document Center, where all the records of Nazi party organizations and personnel, including the SS, were kept—and finds out Frederica was lying: Her father was a committed Nazi and Frederica’s husband was in fact in the SS.

Danny applies to his base commander for permission to marry the German national Frederica.

Living in the apartment below Frederica is Herr Stieber (O.E. Hasse), who humorously admits he is a Russian spy. He tells Danny he feeds information to the Russians on the number of American planes flying in supplies to Berlin.

Stieber is an important character in the film. He develops a suspicion for Frederica. He has to deliver Danny’s papers for her to fill out for their permission to marry. He also has another letter for her, from America. Frederica rips open the letter from America; it contains a photograph of a man in his 30s standing in front of a shop, “Mirbach’s Camera Shop.” Written on the photograph, in German, are the words: “Darling, here is the new shop. Love, Ernst.” Herr Stieber knows that Frederica’s husband is not dead but is in America, the same man we know was in the SS; Frederica had deceived Danny and was only using him to get to the United States and to her ex-husband. Of course, Danny learns of Frederica’s deceit, thanks to Stieber. (Maybe Frederica will try her wiles with another naïve American GI, we can presume, if it doesn’t work out.)

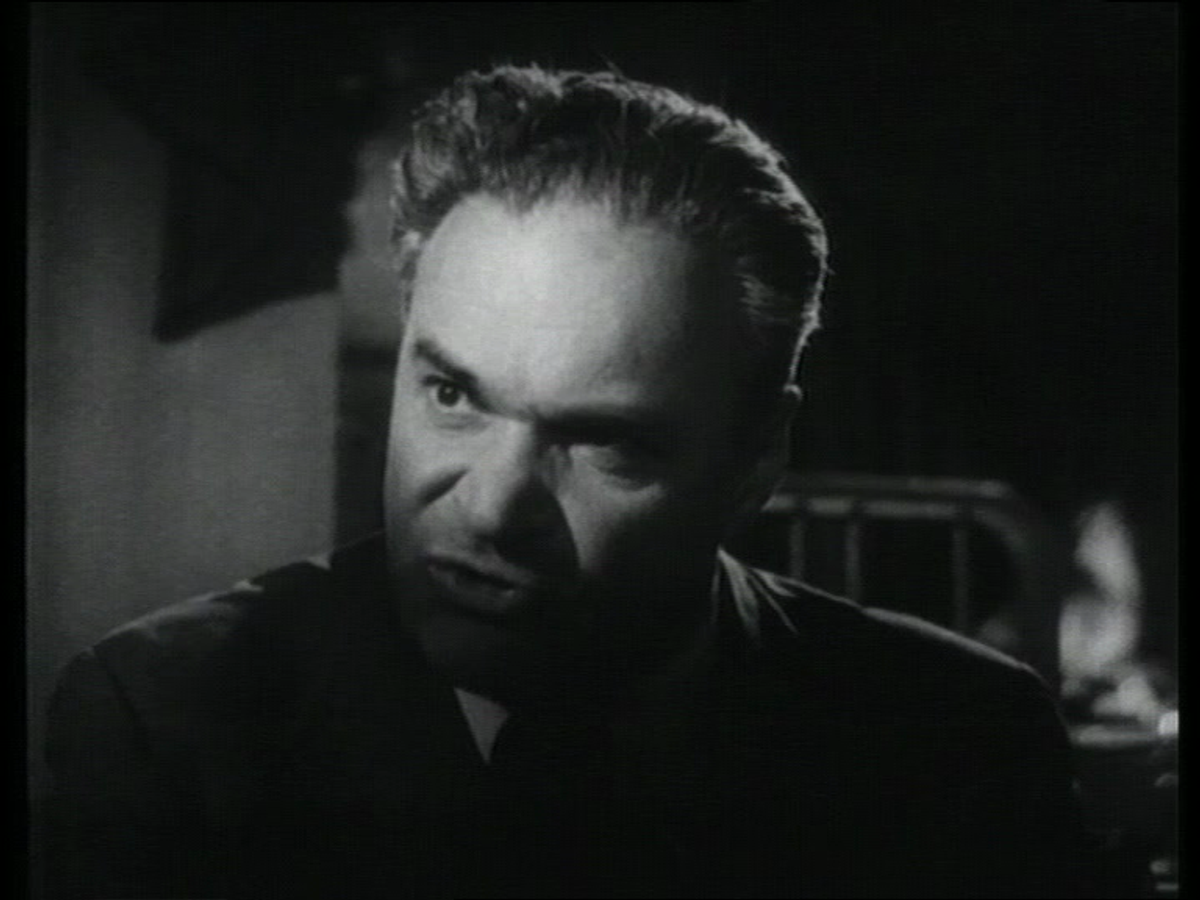

Watch on the Rhine (1943)

Paul Lukas and Bette Davis star in this well-meaning but highly propagandized message movie, based on Lillian Hellman’s play. It effectively advocates—is a virtual plea for—murdering your political opponents, even if you’re not at actual war with them.

It is 1940, and we are introduced to a well-known intellectual and leader of the anti-fascist resistance, a German named Kurt Muller (Lukas), who is exiled in the United States along with his American wife, Sara, played by Bette Davis, and their three children. Sara comes from a well-to-do and well-connected Washington, D.C., family, who are of course staunchly anti-Nazi but don’t really understand how bad things are in Germany under the Nazis.

Kurt Muller does what he must do. In Washington, D.C., in a garden shed on the estate of Sara’s family, he liquidates the Romanian informer and blackmailer Teck de Brancovis (George Coulouris), who is also staying in the house of Sara’s mother, by shooting him with his revolver. This hapless man is not even a fascist, has not yet done anything to anybody but is obviously somebody “weak” and indifferent to the fates of those who might fight the Axis. Of course, Brancovis is a sleazy, greedy, and thoroughly venal man.

The murder is perpetrated on American soil, right in the heart of Washington. At the time the film was set (1940), the United States was not at war with Nazi Germany nor with German’s Axis ally Romania. The only thing of which the iron necessity of liquidation reminds me as a viewer is that this was how the communists in Russia dealt with class enemies in their various inventions but not at all what you would expect, in terms of humane behavior, from the noble Kurt Muller.

Kurt Muller tells Brancovis he wishes he didn’t have to do what he is going to do and that he, Kurt Muller, must now kill him because Brancovis is weak and poses a danger to the greater goal. Later, Muller goes to say goodbye to his children before he is on his way back to Germany. His mission is a rather fantastic enterprise anyway, but somehow Hellman thought this a plausible way to justify her good zealot, the underground leader Kurt Muller, as though this one man meant so much in the context of the upheaval that was going on in Europe. Muller, with his disheveled hair and dirty clothes (clothes he has dirtied owing to his struggle to kill Brancovis), comes back from his murder to tell his kids piously that he did wrong but that it was for the greater good. An idealist must kill for the good of all mankind, and Muller has murdered Brancovis in cold blood: not a hero but a henchman.

Marc Svetov is a translator, fiction writer, and writer about film.