Dreyfus, Zionism, and Sartre

Captain Alfred Dreyfus would have been 162 years old today. His legacy on the left is dying, while the malice that targeted him is alive and well.

I spent most of the summer in Paris, where sidewalk tables were packed with refugees from lockdown, most of them gabbing, drinking, and vaping. (“Belle Vape,” one store’s sign read.) If you were alone, the unspoken rule seemed to be that one must smoke and stare into space instead of looking at an iPhone. Some people even read print newspapers. Belleville, my neighborhood, had five bookstores within a narrow radius, approximately as many as in the entire borough of Brooklyn, thanks to a French law forbidding booksellers to undercut one another’s prices—a blow to Amazon unimaginable in the monopoly-addicted United States.

On Shabbat, I went to a synagogue where the aliyahs were auctioned off and teenagers expertly chanted the grand and solemn Sephardic trope. A few blocks away stood a row of COVID-masked Chinese prostitutes, each separated by a 20-foot sanitary interval, studying male passersby for signs of interest.

Paris’ restaurants, which survived coronavirus with the help of an insanely generous government aid package, are as distinguished as ever. The arts are back, too. I went to the low-rent theater group El Clan Destino, headed by Argentine Jew Diego Stirman, and saw a comic sketch where someone went back in time to chop off Hitler’s head, only to discover afterward that he’d actually decapitated Hitler’s downstairs neighbor, one Samuel Goldenberg. “Encore un Juif!” the actors lamented.

In Paris I did something that is even more forbidden in America than smoking or laughter—I watched Roman Polanski’s J’Accuse, which won the 2019 Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival but has yet to appear in theaters or on streaming in the U.S., presumably due to the director’s 1978 flight from the country after he pleaded guilty to unlawful sex with a minor. The film is a small masterpiece, and I hope you get to see it someday, whatever you think about Polanski’s morals.

The Dreyfus affair was the first culture war, with half of France gripped by the ironclad conviction that Dreyfus must be guilty, while the other half doubted the flimsy evidence against him. It all started with the famous bordereau, a note giving details about French artillery that was fished out of the wastebasket of Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, the German military attaché in Paris. The bordereau wasn’t in Dreyfus’ handwriting, and nothing particularly suggested that he might be Schwartzkoppen’s informant. But Dreyfus was convicted and sent to Devil’s Island off the coast of Guiana, where he was shackled to his bed at night, the island’s sole prisoner. His guards were forbidden to speak to him, and the rotting scraps of food he was given destroyed his health.

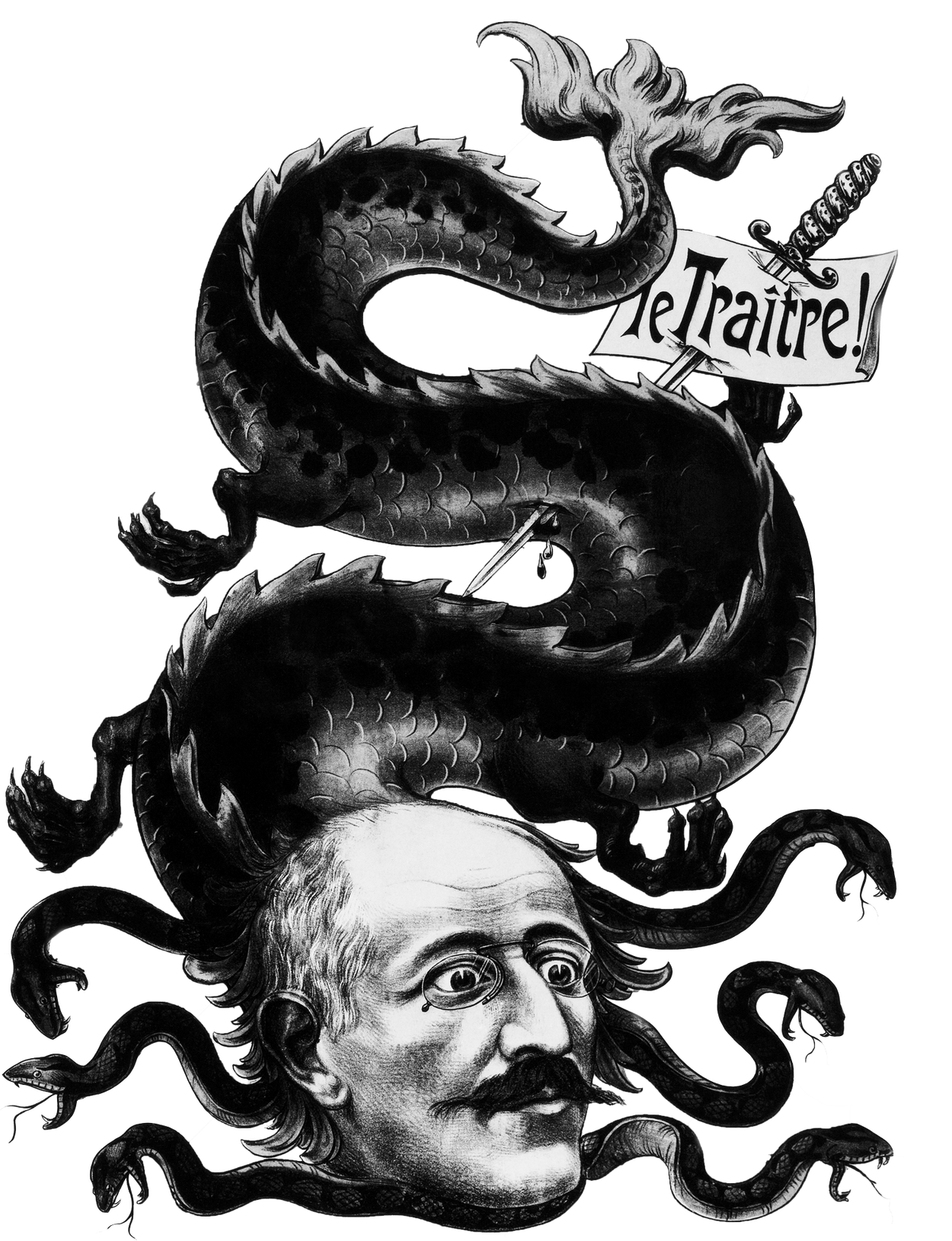

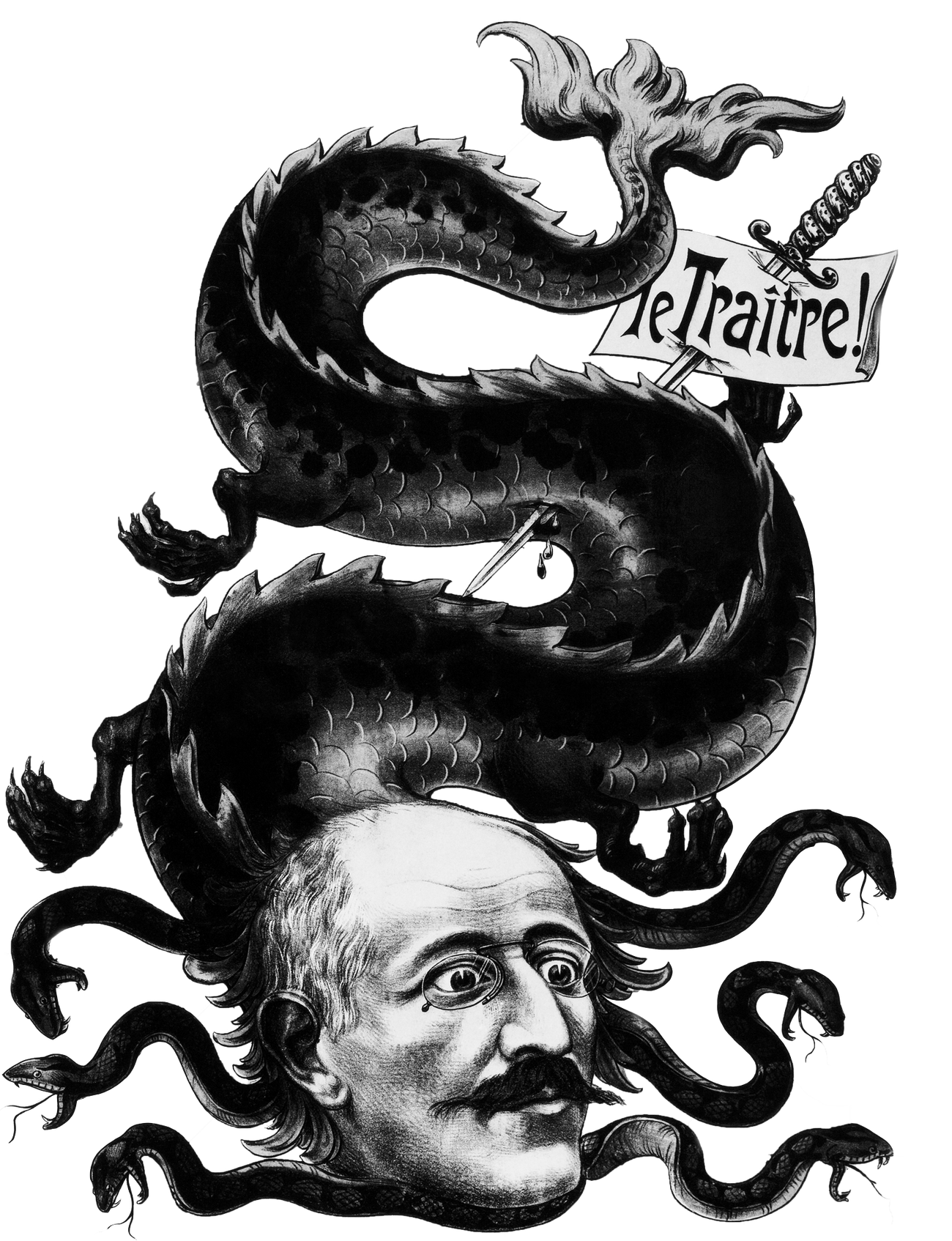

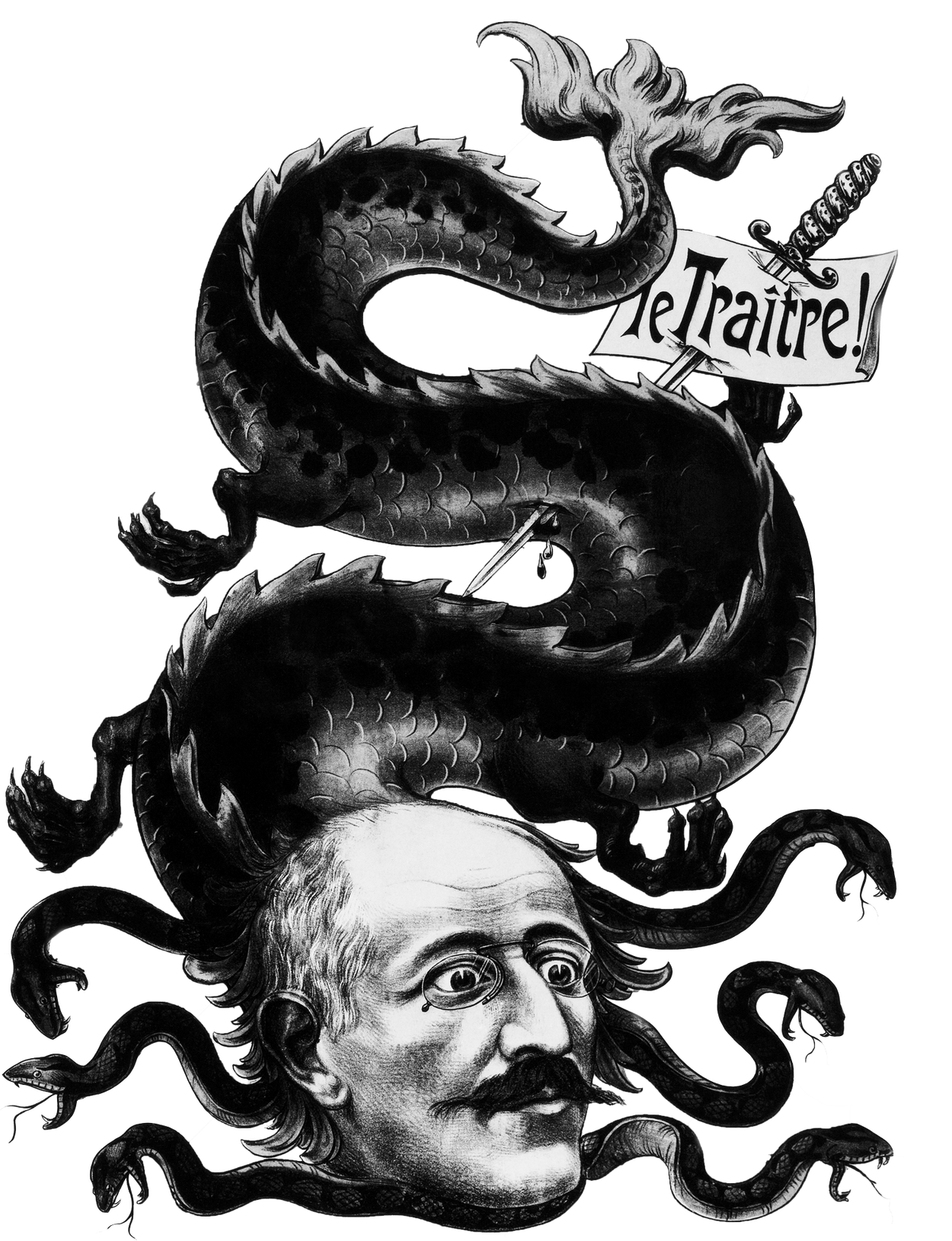

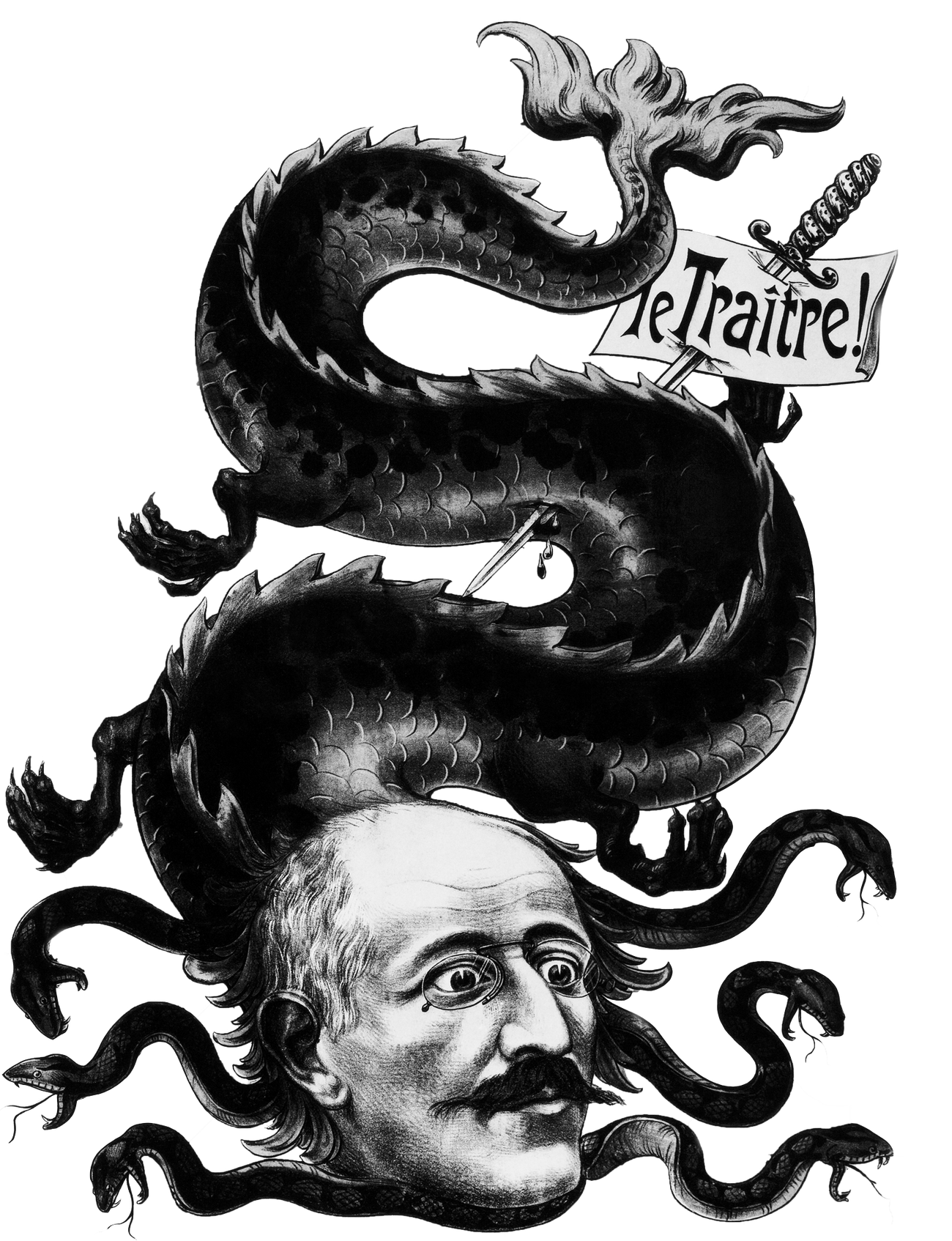

The Dreyfusard intellectuals—a term that originated with the Dreyfus affair—believed that only a fair legal process could yield the truth, while anti-Dreyfusards trusted the word of the army. For the mob out for Dreyfus’ blood, evidence didn’t matter. Dreyfus had to be guilty, since the generals who attacked him represented France and the captain was, after all, a Jew. But the Dreyfusards had a growing audience, too. When Zola’s bombshell op-ed “J’Accuse” appeared in the newspaper L’Aurore, the issue sold 300,000 copies.

The Dreyfus affair presented a clear-cut battle—between the liberal credo of equal protection and reactionary belief in the army’s authority—to which America’s current culture war offers a brutally depressing contrast. America’s right wing is loyal to a clownish ex-president with his false claims of electoral fraud, while “the left” scorns due process, free speech, equal rights, and critical thought. Neither side believes in fair trials. Major liberal organizations now stand up for censorship and injustice, as long as the victims are deemed proper targets because they are the wrong race or gender, or have the wrong ideas. The ACLU filed suit against the reform of Title IX under former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, because the erstwhile champions of civil liberty were alarmed that universities might allow people charged with sexual harassment to defend themselves. President Biden is actively trying to reinstitute the Title IX persecutions that he spearheaded during the Obama years.

There are many Dreyfuses in American prisons, some of them put there with the help of our vice president when she was attorney general of California. Meanwhile, the president pursues a drug war that imposes harsh sentences on low-level street sellers, and he has said not a word since entering office about the barbaric overuse of solitary confinement in our prison system.

When Dreyfus returned to France from Devil’s Island for his second trial, he could barely speak or walk. He stuffed his uniform when he appeared in court so he would look less emaciated. He was convicted again on the basis of fake evidence, then pardoned (the military men who hounded him were also pardoned). Finally exonerated in 1906, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur. In 1908 an assassin’s bullet grazed Dreyfus while he attended the transferring of Zola’s remains to the Pantheon. The would-be murderer was acquitted by a sympathetic court. The big lie about Dreyfus’ guilt and the sinister Jewish conspiracy behind him lasted for decades, fuel for Charles Maurras’s proto-fascist party Action française.

Polanski’s film begins with Dreyfus’ degradation in January 1895, a staggering legendary moment. For the right-wing novelist Maurice Barrès, Dreyfus’ dishonoring was “more exciting than the guillotine.” Dreyfus’ sword was ceremonially broken and his epaulets and stripes ripped off while the army pronounced him a traitor to France. A nearby crowd howled for the death of the Jews. Dreyfus called out that his accusers were “cowards,” a precisely fitting word for the military’s later cover-up of their crime against him.

The main focus of Polanski’s J’Accuse is not Dreyfus but his defender, Marie-Georges Picquart, the Catholic officer who in 1896 first discovered that the handwriting on the bordereau exactly matched the letters of Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, who was the real traitor. The mildly antisemitic Picquart, played to perfection by Jean Dujardin, resembles Dreyfus himself—stiff, somewhat haughty, not particularly likable. Picquart spent a year in prison for his defense of Dreyfus, and also fought a duel against Lieutenant Hubert-Joseph Henry, who had forged evidence to condemn the Jewish captain.

In the final scene of Polanski’s movie, Dreyfus comes to see Picquart to complain that he has not been given the rank he deserved. His years of imprisonment were not taken into account, so he was promoted only to commander, while Picquart had become a general—Dreyfus would never join the General Staff. Picquart rigidly explains that he can do nothing about the situation, and Dreyfus is not appeased. This was their last meeting, the end of an unlikely alliance between two touchy, stubborn personalities, both devoted to a France that they desperately hoped would choose reason over prejudice.

Picquart shared with Dreyfus the naïve belief that the facts would win out in the end—every thinking person would condemn the generals and realize that Dreyfus was innocent. But the anti-Dreyfus camp remained strong even in the face of crystal-clear evidence. Reason could not convince the conspiracy theorists, who simply knew that Dreyfus was guilty.

The Dreyfusards, too, needed more than just material evidence: Dreyfus’ intense patriotism played a key role in his defense. Dreyfus was not a French Jew so much as a proud Frenchman who just happened to be a Jew. He was also an Alsatian who had always detested the German occupiers of his land, and he attracted Alsatian supporters eager to show their loyalty to France. As the affair dragged on, the Dreyfusards promoted their own conspiracy theories about Jesuit influence, so that being pro-Dreyfus started to mean being anti-Jesuit.

Hannah Arendt gives an account of the Dreyfus affair at the end of Antisemitism, the first volume of her 1951 Origins of Totalitarianism. The book’s final sentence reads: “The only visible result [of the Dreyfus affair] was that it gave birth to the Zionist movement—the only political answer Jews have ever found to antisemitism and the only ideology in which they have ever taken seriously a hostility that would place them in the center of world events.”

Arendt relied on Theodor Herzl’s passing comment that the Dreyfus affair first set him on the path to Zionism. True, Herzl was in the crowd at Dreyfus’ degradation, but a closer look at Herzl’s diaries reveals that Viennese antisemitism was the real spur for his Zionism.

But Arendt is right that the anti-Dreyfusards’ exterminationist antisemitism should have made clear to the Jews of Europe that they were living on borrowed time. She cites the 1899 charity campaign for the widow of Lieutenant Henry, who had committed suicide after his forgery was revealed. Many donors supplied not only money for the “Henry memorial,” but also grotesque solutions to the Jewish question: “Jews were to be torn to pieces like Marsyas in the Greek myth; Reinach [a prominent Jewish Dreyfusard] ought to be boiled alive; Jews should be stewed in oil or pierced to death with needles; they should be ‘circumcised up to the neck.’” The historian Ruth Harris notes that “one contributor propos[ed] to make violin strings out of Jewish intestines.” A cook wanted to bake Jews in his ovens. These vile testimonies, scarcely to be outdone even by the Jew-hating fanatics on contemporary Twitter, appeared in La Libre Parole, founded by Édouard Drumont, the father of modern French antisemitism.

The Dreyfus affair also threw its long shadow over Jean-Paul Sartre, who must have been thinking of the anti-Dreyfusards when he described the antisemite’s psychology in his book Anti-Semite and Jew, published in 1946. Antisemites, Sartre wrote, are frightened by any search for the truth (like the one demanded by Dreyfus and his allies). Nourished by the antisemitic myth, they ignore evidence-based arguments and debate. Since they are afraid of reason, they wish to lead the kind of life wherein reasoning and research play only a subordinate role. Only a strong emotional bias can give a lightninglike certainty; it alone can hold reason on a leash; it alone can remain impervious to experience and last a lifetime. Mere reason could not sway the anti-Dreyfusards, whose message was passed on to the exterminationist antisemites of Vichy France.

“The antisemite has chosen hate because hate is a faith,” Sartre continues. “At the outset he has chosen to devaluate words and reasons.” Antisemites “know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge ... they even like to play with discourse for, by giving ridiculous reasons, they discredit the seriousness of their interlocutors. They delight in acting in bad faith, since they seek not to persuade by sound argument but to intimidate and disconcert.”

A Jew most often combats the antisemite’s onslaught by being reasonable. He asks for fair treatment, as Dreyfus did, but this, Sartre points out, is a frail defense, which causes the Jew to further victimize himself, while inflaming the malice of his accusers.

Sartre has gotten much bad press for his claim that “it is the antisemite who makes the Jew.” But Sartre was being polemical—he ignored the rich resources of Jewish self-definition so he could focus on the Jew who was anxious about being a Jew. Such an anxious, inauthentic Jew, Sartre says, “has allowed himself to be persuaded by the anti-Semites ... He admits with them that, if there is a Jew, he must have the characteristics with which popular malevolence endows him, and his effort is to constitute himself a martyr, in the proper sense of the term [i.e., a witness], that is, to prove in his person that there are no Jews.”

Sartre’s analysis applies to those Jewish anti-Zionists who wish to wipe Jewish nationalism from the map and turn the Jew into the universal man or woman—a purely virtuous apostle of human rights (while at the same time applauding Palestinian nationalism). By contrast, Sartre was a committed Zionist who argued that the United Nations ought to have armed the Jews when the British departed from Palestine. In 1949, he said that the creation of Israel was one of the rare events that “allows us to preserve hope.” “I will never abandon this constantly threatened country whose existence ought not to be put into question,” he remarked in 1976. In Anti-Semite and Jew, composed before the birth of Israel, he wrote that the Jew “may also be led by his choice of authenticity to seek the creation of a Jewish nation possessing its own soil and autonomy.” Though Sartre also says one can be an authentic French Jew, this seems a less attractive option given pervasive French anti-Semitism.

For Sartre, as for Herzl, the Jew’s problem was rootlessness: the Jew ran the risk of becoming nothing except a defender of universal rights, and so not Jewish at all. By default, his loyalty, like Dreyfus’s, would belong to the nation-state that oppressed him. A new Jewish rootedness—Zionism—was needed instead. And so Sartre’s logic leads in a Zionist direction, though this remains less than explicit in Anti-Semite and Jew.

Near the end of his life, Sartre gave a lengthy interview to Benny Lévy, his young Maoist secretary, who later abandoned Marx and became a rabbi in Israel. Sartre shocked his leftist comrades by telling Lévy that Jewish messianism was superior to the Marxist ideology he had long championed. For the Jews, Sartre argued, each virtuous act is justified because it contributes to the coming of the Messiah, and this seemed to him a better idea than Marxist class warfare, since it spoke to Sartre’s ideal of committed personal action.

Most European Jews, instead of emigrating to Palestine, had either remained loyal like Dreyfus to the nations that scorned them, or simply hoped they could survive the coming persecution without leaving their homes. Their hopes were ruined. Outside Paris’ schools, the visitor can now see plaques commemorating the thousands of Jewish children murdered by the Nazis with the active assistance of the French state.

Dreyfus’ nephews fought and died for France in World War I. His son Pierre, who passed through the hell of Verdun, earned the Croix de guerre. Dreyfus himself died in 1935, too early to see French gendarmes deport his favorite granddaughter, Madeline, to Auschwitz.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.