Jack Mormons

When I left the church, I found myself, and some Jewish roots

There is no more misunderstood place on Earth than Salt Lake City. Unless you were raised in the area you probably think of SLC as one of the nation’s great red-state bastions, a city run by religious fanatics who itch to create an unironic version of the Handmaid’s Tale and are only thwarted in constructing this dystopia by that pesky thing called the U.S. Constitution. “Damn you, Roe v. Wade! And, damn you U.S. Constitution with your separation of church and state—and reifying protections of the female body.” (This is how your coastal voice sounds: postmodern, arrogant, and entirely uninterested in the intricacies of any American cultures outside of the coasts.)

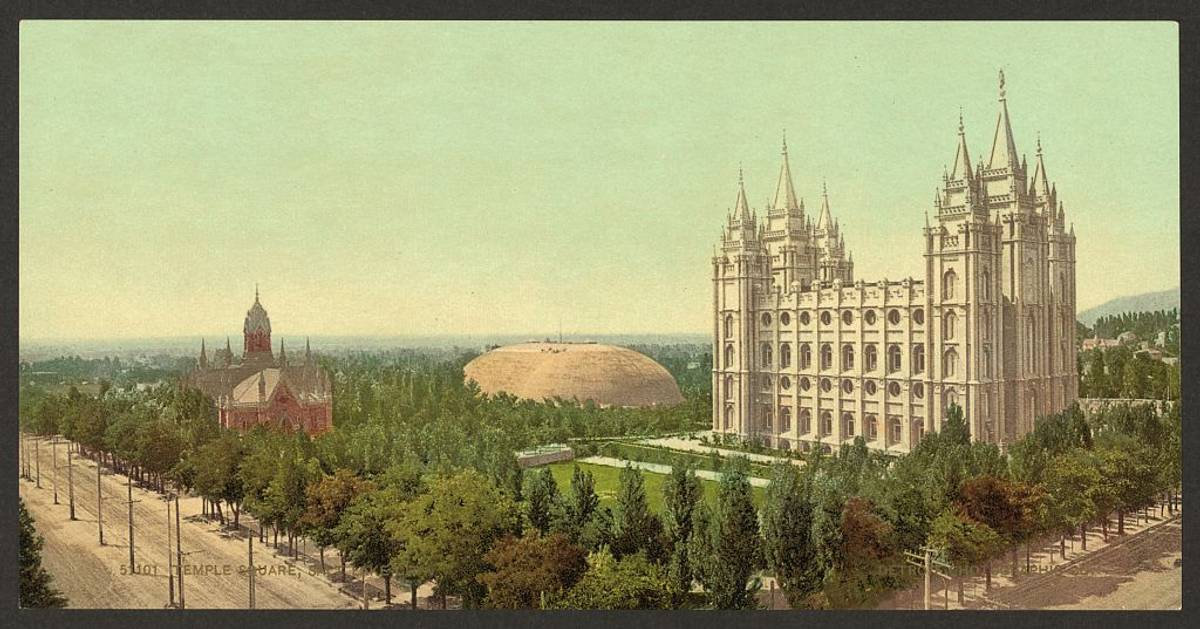

Utah Mormonism is America’s largest homegrown religion with an origin story of persecution that mirrors that of Judaism in Europe and yet almost no one, including those in the supposed knowing classes, learn anything about its culture other than jokes about polygamy. As a result, in the 180 years since Mormons were driven out of Missouri—the governor declaring an extermination order that allowed nativists to ransack Mormon settlements and assault, if not murder, religious adherents—popular opinion about Mormons has changed very little. After the Mormons fled to Western Illinois, they were met with similar contempt, and their prophet, Joseph Smith, was eventually captured, jailed, and soon after shot and killed by anti-Mormon nativist mobs. Brigham Young then assumed leadership of the Mormon congregations and initiated the church’s exodus across the West. At the end of a 1,300-mile trek, Mormons arrived in a frozen desert snuggled between the 9,000-foot Wasatch Mountains and the remnant of a massive ancient lake that once covered much of the Utah region, a dead sea with a strange color and a worse odor.

Great Salt Lake City, as it was originally called, represents both the Vatican and Jerusalem of Mormon culture. Today, Utah’s capital stands also as ground zero of the LDS church’s demise within the state it founded. It’s been three and a half decades since a Mormon represented Utah’s capital as their chief executive and a decade more since a Republican held the office. To experience the devout, dominating, and highly righteous Mormon culture most people expect to find in Utah you’ll need to drive 45 miles south of Salt Lake, to Provo.

Last year, the possibility of a Mormon returning to Salt Lake City’s highest office became a major talking point throughout Utah. Ex-Mayor Rocky Anderson wrote in a widely shared Facebook post arguing that the city’s independence and longstanding progressive tradition was “threatened” by any candidate adherent to the Mormon faith “who seems willing to do the bidding of the church.” Pundits and commentators rightly called Anderson’s view bigoted and reminiscent of the nativist political prejudices that drove Mormons to Utah in the first place. Utah state Sen. Luz Escamilla, the election runner-up, may have purposefully hid her Mormon faith or, at minimum, strategically deemphasized it prior to the summer run-off vote. Had more SLC voters known she was in fact Mormon, she probably wouldn’t have made it through to the final stage of the election process.

Politically and socially, Salt Lake is in fact a progressive “blue” island inside the red sea of conservative Utah—and one of the strongest and most consistently progressive city governments in the entire nation. The aforementioned Anderson was a fire-breathing antagonist who took crap from no one. Check out this 2007 interview he did with Fox News where you can see him go toe to toe with Bill O’Reilly. Anderson regularly toured the leftist protest scene in 2006-07 demanding Bush’s impeachment, and eventually debated the efficacy of impeachment (for lying about Iraq’s WMDs) with Sean Hannity in a truly surreal, almost WWE-style televised event.

Overtly anti-Mormon in every breath he took while Salt Lake mayor, Anderson was entirely aware his popularity—and electability—depended on bashing the Mormon church whenever possible. I know this because I was his communications director from late 2005 to early 2006-ish. During this era, I spoke to him multiple times a day, wrote his speeches, and outlined his talking points to the media. He ignored almost all those talking points (and most of my media strategy, too), just as he did my advice to strategically flatter rather than insult Mormon Republicans in the Utah legislature. Anderson wanted to fight. Desperately. Taking down the LDS church, especially its “retardlicans” remains one of his favorite pastimes.

The phrase “retardlicans” is my father’s. To tell you the truth, I’m not sure I ever heard Anderson use it. If you knew anything about Salt Lake politics you might understand why the two men are easy to confuse—the infamous ex-mayor of Salt Lake and my sort-of famous Utah activist father ... my two tyrannical Jack Mormon ex-bosses.

“Jack Mormon” means less than fully devout, halfhearted, or completely disaffected Mormons. I place all ex-Mormon—including anti-Mormon—culture under the broad umbrella of “Jack Mormonism.” Many Utah commentators would take issue with my definition, but those people can go suck an egg. I have three graduate degrees in three different fields, including a Ph.D. in American culture; therefore, I am not just correct, but superior—a standing, or ambition, that I share with the coastal crowd.

In my early pursuit of intellectual superiority over others, I decided to leave the church. At age 13, around a Boy Scout campfire in the Uinta Mountains, I announced: “I no longer believe in God.” In this entirely Mormon troop, both my fellow preteen scouts and the adult scout leaders quickly informed me I was “going to hell.” When I teared up and walked back to the open-air, wooden bunk beds, only one person followed me back—a boy who had never been nice to me before (or since). He said, “I still love you, even when you insult our Lord and Savior.”

When I refused to go to church soon afterwards, my father responded by “fining” me $20 for every day of church I missed. He then started fining me more for swearing, talking back to him, and for not doing my three hours’ worth of daily household chores. When it came time to write the payment check for my private school in downtown Salt Lake, he wrote it minus the $1,200 or so he calculated I “owed” him. Things did not progress well from there.

Mormon culture is hypermasculine and male-dominated to an extent rarely seen in polite society anymore, at least not in the industrialized West. The devout alpha Mormon will be celebrated like the climax scene in Tinto Brass’ Caligula, except in G-rated form (OK, maybe this isn’t the best metaphor). An alpha Jack Mormon male will be met with the reverse. The rebel’s alpha status will only strengthen the father’s resolve to exert control over their fading ancestral and spiritual legacy—which Mormons see as one and the same.

Losing a dominant son to the proverbial dark side is a Mormon failure of colossal proportions. In a desperate attempt to get the wayward alpha back to the “tried and true,” the Mormon father will exert every means possible. At age 17, my father signed paperwork to forcibly lock me away in a youth psychiatric ward. I was escorted there by police. They came to my parents’ home, a bright purple and blue monstrosity with tall castle turrets my father designed to look like a Disneyland castle (this isn’t some kind of metaphor). The police entered this ridiculous domicile and told me I was the one who was crazy.

“Why’s that?” I said.

“Because your father says so,” the officers replied. There were three of them.

“Who cares what he thinks,” I said.

“I hear ya. He has the power here, though. You do not,” the lead officer said. The other two stood there with their hands at ready, resting on their firearms.

“You have two options,” he said.

“What are they?”

“Voluntarily, ride in the police car with me,” the officer stated flatly.

“—or?” I asked.

“—strapped down in a gurney and put in an ambulance.”

He seemed like a pretty good guy, just following procedures.

“Third option?” I asked him.

“Nope.”

My sister rode in the police car with me, wanting to show support somehow. Dad had the power and he was going to use it, consequences be damned. It happened to a lot of rebellious Mormon kids in the 1990s SLC punk-rock scene—their parents forcibly placing them in mental or rehab facilities for extended periods of time to teach them a lesson about staying on the “straight and narrow.”

I personally know at least two other people to whom something similar happened, one of whom was Brit McConkie—my best friend’s older sibling and also the BFF of my own older brother.

At age 16, the McConkie parents found Brit’s stash of drugs. Pot. Mushrooms. Maybe some LSD. Even he can’t remember exactly. When they found the stash, the scene was like something out of the Nancy Reagan-era “Just Say No” TV ads, except there was nothing unintentionally comedic or heartwarming about what his parents did in response. They locked him up indefinitely in a rehabilitation facility based in Provo.

“They would surround you on all sides. Everyone in the room. Forcibly make you conform to their way of thinking. I saw kids made to stand for 12 hours straight while dozens of people berated them until they literally broke their will,” Brit told me recently, recalling his more than yearlong “rehab” ordeal.

Brit’s grand-uncle is Bruce R. McConkie, a general authority of the Mormon church who wrote a famous piece of 20th-century Mormon doctrine, and regularly gave dictatorial speeches at LDS general conferences about the horrors of abandoning Mormonism’s tried-and-true path. There was simply no way this family was going to stand for using “hippie drugs,” or any shit like that—except they didn’t say shit … probably something more like “crapola.”

Brit quickly figured out there was no point in resisting the Provo rehab people. So, he cooperated with his captors enough to obtain some degree of freedom of movement. Eventually, he built up enough “privileges” to watch over other patients without staff supervision. He then used this freedom to escape.

“I told the other kid I was with, ‘Dude, I’m getting on this bus and getting the hell out of here. I’m not going to tell you where I’m headed unless you come with me,’” he said, laughing in a dull, uncomfortable way that masks half-resolved childhood trauma.

Shortly afterwards, there were flyers with Brit’s long-haired face all around town. My older brother knew where he was hiding, so did most of the other Jack Mormon skateboarder kids I grew up with. Many people took turns hiding him. The whole thing was pretty dramatic all around.

Unlike my friend, almost no one knew what happened to me. My parents lied to my girlfriend, my school, and even my older brother—probably because he would have driven a dump truck through the front door of that place to break me out of there.

In total, I was in that youth psych facility for about a month, but I’m not really sure. Forced medication. Forced therapy sessions. You lose not only track of time, but your sense of self in these places—and that is exactly their intention.

If you’re not from Utah, you may not realize that it is remarkably easy for parents to lock their teenagers away in mental facilities or rehab centers. All they need is a sympathetic psychiatrist of their same faith who will agree their child is “out of control.”

There was a 13-year-old girl in there with me. Thirteen. Her Mormon parents caught her having sex with an older neighborhood boy in her bedroom ... on top of her Care Bear sheets. They just couldn’t cope. She had been in there for nine months.

When my parents finally came to their senses and let me out, the girl was still in there—and, no closer to getting out. But, I’m sure she is totally over it now.

PTSD affects me on a cellular level. My nervous system is now sensitive to, well, everything—hot foods, bright lights, and especially gaslighting. Anyone trying to tell me something about my lived experience (now I sound like you coastal snobs) is “crazy” or “ridiculous” will inevitably create substantial reactions within my body that will last for weeks. I believe we can accurately call this a trigger.

For Utahans, Salt Lake is Gomorrah and has been for a very long time. Today, Jack Mormons like me and Brit rule the place. Salt Lake politics making a little more sense now? Good. Let’s move on to my other grievances with coastal prejudices.

When I began graduate school in journalism at NYU, I had a lot of culture shock, not because of New York’s Democratic politics, “multiculturalism,” or anything like that. I just couldn’t believe how elitist, narrow-minded, and dismissive nearly everyone was compared to the people of Salt Lake City.

In my J-school assignments, I wanted to write about my culture, specifically Salt Lake’s uniquely aggressive, super creative, and artistic punk-rock scene—a music scene that produced Iceburn and their unreal Hephaestus album, which is one of American punk’s greatest achievements—a 75-minute hard-edged symphony (with no stops) that seamlessly mixes metal, jazz, and math rock into a coherent whole.

Who else other than a bunch of kids trapped under the Zion curtain would ever even try to combine Paranoid, Bitches Brew, and Spiderland? Had Gentry Densley—Iceburn’s lead—done his work in LA, or Chicago he would be known as one of the most unique guitarists since Hendrix. Instead, he toils in near-total obscurity. (Last time I talked to him, he was working a state job as the librarian for the Salt Lake County Jail.)

I couldn’t find a single media outlet even willing to respond to my pitches about Salt Lake punk rock or Jack Mormon culture. It was all too much for anyone to fathom. Ex-Mormon rebels … Salt Lake punk? “Okey,” people would say, rolling their eyes. There were no angry, aggressive, but also supercreative and artistic ex-Mormons and certainly not a unique punk scene in Salt Lake City. Utah’s capital was full of happy Mormons who have four and five wives. Why didn’t I understand this?

My father’s trauma came from being one of eight children. His Mormon mother was more interested in painting pictures of the Oquirrh Mountains and writing theatrical plays about delightful little fairies than raising him or any of his siblings, especially the later ones—and he was number seven in the litter.

No matter how much my father accomplished—student-body president of his high school, entrance to Stanford followed by graduation from Harvard Medical School—his Mormon mother never bothered to take much notice of him. What she really wanted was for someone to produce her plays, and for her paintings to hang in a gallery somewhere. Those outcomes were simply not possible for a Utah Mormon woman born in the early 1910s. I understand how confined her choices were and the undeniable pull to create your art, and I think my father does as well. But, there is nothing quite like the effect of a mother’s neglect. Someone might get over their father’s lack of interest (I feel I have … mostly), but a mother’s negligence falls into its own separate category of primal wound.

My father is a crazy person, but he’s a lot more mellow about it now. He wouldn’t dare lay a finger on me today (though that may change after this is published). He’s also about to turn 70, has two types of cancer, and he might be dying. I could kick his ass now with one hand tied behind my back. Yes, this is where my thoughts go.

Like the woke crowd, my father has decided to seek his salvation in politics. When he received his cancer diagnosis, the first thing he did was go to the keyboard and write an op-ed column for the Salt Lake Tribune about the state’s environmental policies. He is now a high-profile environmental health activist, regularly writing screeds for the Tribune that condemn the (still mostly Mormon) state legislators for narrow-mindedness, corruption, and their general lack of concern for pollution’s impact. Due to all his regular columns and media appearances, he has become a popular, if not adored figure among the Salt Lake Valley’s progressive community. When I’m back in town, nearly every other time we’re having dinner someone will stop us mid-meal and say:

“Hey, I know you—I really admire what you’re doing. Keep it going,” or some blathering along these lines.

When this happens, I smile and shake my head a bit. I’m happy for him. Happy his life has meaning. Happy people recognize his efforts to change the state. But, inside I want to say, “If you only knew.”

He and my mother eventually stopped trying to prevent me and my three siblings from leaving the church. After a few years, they stopped going as well. It’s a fairly typical Jack Mormon scenario, actually.

Unlike the popular Broadway character Elder Price, a lot of Mormons don’t “just believe.” Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s The Book of Mormon musical is a profane, but also lighthearted spoof of Mormon missionaries. Its portrayal of LDS culture is purely one-dimensional, though.

A great many Mormons have large doubts about the doctrine. They don’t believe the golden plates were real. They don’t believe Joseph Smith, Russell Nelson, or any of the rest of the “quorum of the twelve apostles” leadership have talked directly to God. They don’t believe ancient Israelites made it to America. Nor do they believe good people get to spend eternity in heaven with their families on their “very own planet.” Some conceptualize that vision for what it would be: the bad place ... or as Mormons call it the “terrestrial kingdom.”

There are indeed entirely genuine progressive Mormons who do not care a wit what the LDS leadership says about politics or anything else. Luz Escamilla was not a Manchurian candidate for the LDS leadership, as Anderson implied. From what I hear, people in the trenches of SLC politics preferred her to Erin Mendenhall (the victor).

Progressive Mormons are interesting folk. They see large parts, if not even most, of the Mormon doctrine as absurd on its face, but treat those absurdities as little different than how most Christians treat Leviticus 19:19 or Deuteronomy 25:11-12, or frankly, the ridiculousness of Christ being reborn. Many Mormons look the other way at the kookiness of the LDS origin stories because they have decided the culture that was spawned from them is worthwhile and they’re not interested in starting anew. My friend Brit—remember, the one from the famous Mormon family sent off to “rehab”—he is now one of these people.

Brit ended up marrying a Mormon widow with two little girls. “I go [to church] now for them—but I don’t believe any of this crap. For some reason, from a really young age I just didn’t believe it. Intuition I guess.” Due to his father’s work, Brit spent a lot of time in Los Angeles during his adolescence. There, he picked up a surfer twang he’s never discarded.

“I’m not gifted with numbers, but I had an idea of how many people there are, and I was like—dude—there is just no way this little church in Utah had figured it all out. This one person Joseph Smith did not come up with the secret to the whole world. … The ‘entitled one.’ I didn’t think it was very Christ-like, you know.”

In revisiting the rehab experience—like me—he couldn’t recall exactly how long he spent in confinement. “I went for three months, escaped for four-and-a-half months. Then, they caught me and put me back in there for like another five months.” It was more his mother that insisted he go. His dad with the famous Mormon ancestry was more on the fence. That surprised me.

Apparently, it was one of our Mormon neighbors who convinced Brit’s mother a no-holds-barred practice in Provo was the right direction. “‘If your kid is doing drugs and not going to school, take them to this program and it will turn them around,’—that’s what happened,” he said.

In the 95% Mormon neighborhood of Holladay, Utah, where Brit and I were raised, tolerance was merely a façade the 19-year-old men donned prior to boarding the plane on their missions. Their acceptance of other belief systems and lifestyles is only as deep as the dimples they use to smile through their intense annoyance that Mormonism is not dominating the entire world. They are after all, “the one true church.”

The Mormon exterior of tolerance is mere realpolitick. Due to their disastrous experience with American (mostly Protestant) nativism, Mormons learned that when outside their home turf they must lower their tone of superiority and pretend to accept others’ belief systems or face the kind of blowback that sent them to Utah in the first place.

Perhaps Mormons become so upset when members leave because, like Judaism, Mormonism is both a religion and an ethnicity. Brigham Young is my great-great-great-grand uncle. But don’t be too impressed. It isn’t that hard to be related to a man who, at one point, had 29 wives and who-the-hell knows how many descendants. It’s like being related to Genghis Kahn.

“Race” is a silly and outdated 19th-century concept fraught with logical and factual absurdities. The persistence of the concept’s use in our culture says disturbing things about how little we have progressed intellectually. However, when talking about the pioneers who traveled to the Utah territory in the middle of the 19th century—most of them English in origin with later waves of Swedes and Danes coming in the last part of the century—we can accurately talk about a “tribe.”

As with the Vikings, the Moors, or any other group of founders or invaders, the original 60-70,000 Mormon pioneers had an inevitable effect on the biology of the eventual Mormon community. Ernst Mayr coined the term “founder effect” (I am an academic, you see) to describe a loss in genetic variation that occurs when a new population—especially of, say, an island variety—is established by a small number of ancestors who then become isolated from the larger species.

During the 19th century, Utah was functionally an island. Due to persecution, Jewish communities were often functional islands inside Europe as well. In the West, people once used to openly talk about the Jewish “look.” When I moved from Utah to New York to attend NYU—and encountered Jewish communities for the first time—I found these stereotypes highly exaggerated. Some had a small ring of truth, though. Once I realized that, I started to think about whether there was in fact a Mormon look also.

If scouting for it, you can see the founder effect in many Mormons’ appearance: a round, small-nosed, fairylike face that seemingly never gets chiseled no matter how much weight you lose. It looks better on the women than the men. Mormon men tend to have a wispy, blond, towheaded look that persists even in adulthood ... fair-skinned, blond-haired men with receding hairlines resembling perpetual children standing next to their Emma Watson-looking wives. Four children between them. One in each of their arms, another in the stroller, and one more pulling on the pant legs. I see this scene at the Salt Lake airport whenever I get off the plane to visit family. Once I encounter it, I know two things: A) I’m home B) I’m triggered.

That first night in the psych facility for teenage Mormon castoffs, I just kept saying, “I’m a straight-A student. ... I don’t do drugs. ... I haven’t hurt anyone. … There is no reason for me to be here.”

No one cared. During intake, the staff told me to be quiet and sign the paperwork acknowledging that I “voluntarily” put myself in that place. I refused. They then brought in three different “doctors” to explain that “it would be better for me if I did.” Their insistence went on for hours. They really wanted me to sign the paper. I never budged, though. They told me I was the only person who had ever refused to sign.

In retrospect, that refusal to comply remains one of the greatest moments of my life. Ultimately, though, it didn’t prevent them from keeping me there. They took all my belongings, including my clothes and even the Stridex pimple pads my sister kindly brought for me. They said, “you might try to drink the alcohol.” Shortly afterward, I stood in the bathroom, staring in the mirror, planning my escape.

I took apart the bathroom towel rack, then brought its metal rod to my room’s window where I began assessing its use as a club. If I swung the towel rod hard enough could it break through the window’s glass? Clearly, it had been reinforced somehow. Maybe, I could use the rod as a lever to pry the window out of the frame.

After staring at the metal rod in my hand for a minute or two, I decided it wouldn’t work—at least not before two or three orderlies came down the hallway. There would be more of them than I could fight off.

What if I took apart the bed frame piece by piece—was there anything in there that had more weight than that rod? I decided there wasn’t. But, after I took everything off the bed, I discovered the frame was one large, rectangular wooden piece with legs. I decided to see if I could lift the entire thing over my head.

I could.

If I got a running start with the bed frame over my head and threw it full force at the window, what then? I brought the structure up over my head then paced myself backward to the very end of the room.

Standing there, wearing a hospital gown—with a bed frame over my head—I was overwhelmed with the absurdity of my situation and the futility of escaping. I still, though, had to negotiate with myself not to at least try.

I needed to get away … from all of it. I realized then and there I did in fact believe in God. He wanted me to tear it all down, but not with my hands.

So, I made a Viktor Frankl-like compromise with my brain and decided at that moment I would suffer through this for one purpose alone—to tell the story of the ex-Mormon experience. Eventually, they would have to let me out.

Nietzsche once remarked, “if you stare into the abyss—the abyss stares back into you.” After what I went through growing up, no answers or theories have ever been off limits. It’s a somewhat natural response for the betrayal felt by the Jack Mormon mind.

While working and studying in New York there was something I just couldn’t help but notice about the journalism scene there: the Jewishness of the whole thing. Of the nine professors I took graduate courses from at NYU, six were Jewish. Nearly everyone who worked at the think tank where I was employed was also Jewish, and it seemed like one-quarter to one-third of nearly every media outlet I encountered was Jewish as well.

For a while there, I began unfairly associating all the regionalist snobbery I encountered not with the general coastal prejudice of middle America, but with Jewish culture specifically. And, it also just seemed to me that Jews really had a leg up in landing gigs at major journalistic outlets. Maybe there was something to this whole Jews control the media thing. Mormons definitely didn’t.

Now that I’ve offended you, let me risk digging the hole a bit deeper. Putting aside for a moment the breadth and depth of that whole Holocaust thing, Mormons and Jews share a lot in common. Both are hated by the radical left and the radical right almost equally. Both were persecuted by Christians and driven out of nearly every place they ever tried to settle until packing up and building their own Zion. Their population numbers inside the United States are also remarkably similar: Jews: 5-7 million. Mormons: 6 million. Both also clearly view the world in terms of us and them. For Jews, the other is “goy.” For Mormons, it’s “gentiles.” There are, of course, major differences between the two groups’ place in American culture, and this is where I started to become resentful.

While there is hardly a lack of healthy “representation” for Jewish culture in American literature, Hollywood films, or any mass media, Mormon culture remains a joke. Along with “white trash,” which Mormons are associated with, LDS culture is perhaps the last minority group in the United States it is OK to stereotype and stigmatize in polite society.

In creating their Zion, Jews fled to the dead center of the Middle East only to surround themselves with even more people that hate them than hated them in Europe. Whereas, Mormons fled to a (mostly) unclaimed piece of real estate protected by mountains inside the United States. Before declaring Mormons found the better spot, consider that inside the United States most Jews settled on the coasts, alongside the country’s power brokers, whose children they sometimes went to school with, and even married.

Consider the disadvantages of settling in an isolated place, thousands of miles away from the rest of a culture. The only piece of Mormon art that ever got any legs in modern culture is the film Napoleon Dynamite—except almost no one seems aware it was a gigantic inside joke on LDS youth culture. Napoleon is wearing a freakin’ Ricks College T-shirt for half the movie, for Christ’s sake. Gosh.

A few years back, after watching Napoleon Dynamite together and laughing hysterically at all its Mormon references, my mother and I started going through the family albums (every Mormon family has an extensive set). Offhandedly, she mentioned her maternal grandmother—with the surname “Rousch”—was actually a German Jew. She said this with a measure of shame, as if it were merely a curiosity and not something to seriously contemplate.

Of course, I realized what it meant, even if she didn’t: Me and my three siblings were halachically Jewish. We were Jewish enough to have been killed by the Nazis, anyway. Obviously, this was a revelation and it explained a few things; namely, my dark brown, crazy-curly Jewfro hair—and my family’s tendency to endlessly debate politics and history, but never to openly express vulnerability of any kind.

After discovering my own (albeit small) Jewish roots, I can’t say I felt embarrassed to have ever entertained anti-Semitic stereotypes when living in New York. Really, I just wished I had known earlier. Perhaps, I would have been more accepted by my New York journo peers. More than anything, though, I felt glad I could now identify with something other than the philosophical and artistic barrenness of my Mormon background.

In academic life, everyone who is not explicitly anti-Semitic generally recognizes the Jewish people’s outsize impact on Western intellectual life. Spinoza. Marx. Freud. Einstein. Walter Benjamin. Hannah Arendt. Martin Buber. Leo Strauss. The list goes on and on. Whereas, you say the words “Mormon” and “intellectual” in the same sentence and most observers will be waiting for the punchline.

But, like the South Park writers’ satires, this is not really fair. Mormons may not have the long intellectual tradition of the Jewish people, but they are not the ignorant yokels they are often portrayed as. As with Jews, a history of exclusion and persecution has hardened the Mormon mind, and missions to every corner of the world have brought a global awareness to the culture most wouldn’t anticipate. The Jack Mormon scene is–obviously–what I’m concerned with most. It has not produced a truly great mind yet, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it did.

There’s a lot more quirkiness to Northern Utah’s culture than any outsider would ever imagine. As strange as it might sound, I wouldn’t have wanted to grow up anywhere else or have been raised by any other family. Next to me, my father is the weirdest person anyone knows. And that’s something I say with great pride. The man truly does not give a crap what anyone thinks. Inside a 95% Mormon suburb, he designed for himself, and then built, a bright purple castle house, which he still lives in. Above the front door, he has placed his own handpainted, maroon battle lion. It looks nicer than you might think, but no one—including his immediate family—believes anything about this makes sense. I adore this aspect about him. It’s his house, and his vision.

Mormon doctrine bred into my father a relentless work ethic and provider mentality that has served all his children well. He has supported all four of us through bouts of graduate school even when we all strayed thousands of miles from Utah and the Mormon tribe—which is the only thing he’s ever known. Without that support, I absolutely would not be here writing this story today. When I called him last night to let him know a piece would be running today that discussed the “gory details” of my teenage years.” He said, “Well, I’m excited to read it,” knowing full well what happened.

On many levels, he thinks all the difficulty I went through made me a much stronger, more determined person. He’s not wrong. His own father descended from a famous Mormon polygamist by the name of Louis Frederick Moench, the founder of Weber State University. To this day, there is a large, brass statue of the man prominently placed in the center of the school’s Ogden, Utah campus. He’s holding a rolled-up map and a cane, majestically looking off into the distance.

In 1890, when Utah officially outlawed polygamy, L.F. Moench did what nearly all polygamists decided to do at that time: discarded the older of his two wives. Unfortunately, the abandoned “first wife” was our side of the family—my grandfather’s grandmother. Her husband’s choice resulted in exactly the kind of poverty you’d expect for a woman left to provide for her family all alone in the days when riding shotgun on a stagecoach was an actual profession. Eventually, my grandfather made his way to medical school in Chicago. When he got there, he had so little money he was forced into a difficult choice: Buy his medical books in German (only a vestigial language for him) or eat. He would eventually go on to become a well respected Salt Lake-based psychiatrist. He spent nearly all his time in his downtown office. There, he secretly harbored grave doubts about the veracity of the Mormon doctrine and, probably, the mental state of his own wife.

This was my father’s parental background. Why would he know how to properly nurture someone? His depression-era parents never modeled it for him. Like nearly every other Mormon of his generation, my father was thrust into adulthood at the age of 19. After a salutary mission farewell at the ward church house, he was boarded on a plane and sent off to New England to knock on doors.

“Hi there, we’re here to tell you a story about Jesus Christ,” my father would say, introducing himself to strangers while wearing a comically bland outfit and ELDER MOENCH name tag. He did this, that much is certain. However, I’m not sure what he ever genuinely believed. I know this, though: he has never said he is sorry—not for anything he did to me as an adolescent, or for anything else, really.

He did, though, help me out financially while I completed my doctorate. I think this is the only way he knew how to apologize. Occasionally now, he’ll even call me up and we’ll talk about something other than potential trades the Utah Jazz could make. I wouldn’t say that we’re solid now, but the pain is no longer raw. Gay and lesbian ex-Mormons often cannot say the same thing. Many would like to forget everything about their experience growing up Mormon. At times, I can relate. When the police came and surrounded me in my bedroom, I did the same thing most children of abuse do: protect the abusers.

I didn’t tell the officers my father had been throwing me into walls, stair railings, or pinning me down on the floor, requiring my older brother to run across the hall like a linebacker and tackle him off me. Nor did I tell them about how, two years earlier—at age 15—he punched me in the face with a closed fist, then screamed to my mother he would keep doing it unless I did “exactly” as he said.

The next day at junior high school, standing at my locker between classes:

“What’s up with this scab beneath your eye?” a friend asked, his face quickly fading from curious to concerned.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” I replied, telling the truth.

“He hit you—didn’t he?” my friend said intuitively, his face starting to fill with anger. I don’t remember confirming or denying his question. My entire focus was in one direction: not crying hysterically. I desperately needed to avoid more unwanted junior high attention.

“You should tell someone, man,” he said. “If you need a place to crash, come to my place. My parents won’t care.”

My friend’s intentions were good but, in reality, turning in my father was the nuclear option for my Mormon family. It would have had irreparable consequences then, and those same consequences hung over me as I stood there two years later, surrounded by police, two of whom were ready to shoot me in my own bedroom if the situation went south.

Publicly, my father was by all accounts an upstanding, if not kooky and even good-natured member of Holladay’s Mormon community. Who was I? Some hyperrebellious punk kid who had a reputation for problems with authority and getting into fights (can’t imagine why). Assuming the police believed me—and there is a very good chance they would not have—telling the truth would have resulted in my escaping my parents’ ridiculous castle house only to enter the bastille of the foster system. I would only have had to tough out a foster home for a year, but my 7-year-old kid brother, who routinely would squat in the corner of the living room reading books on ancient history, playing out a scene like something out of The Shining while my father had his daily temper tantrums—what would have happened to him? Our older brother has spent his entire legal career in child protection law and that career choice was hardly coincidental.

Had the officers believed me and actually done something about our situation (again, doubtful), my father’s medical career certainly would have been over. In the process, my mother and the members of my immediate family would have lost their sole financial provider. Equally important to me—at that time—had I turned in my Mormon father, he certainly would not have ever paid for my education and, last time I checked, there are no major college scholarships designated for the children of abusive parents. Go to any college scholarship database, remove race and gender from the options, click “filter.” Look at the screen. You’ll see exactly how many options I had.

If you’d ever experienced anything like me or my friends’—or so many gay Mormons’—parental treatment you might understand three things. First, why young men join groups like the Proud Boys when confronted with clue-free, liberal-arts-school grads telling them they’re indelibly “privileged.” Second, why Salt Lake politics are so doggedly anti-Mormon. Third, we get to bash devout Mormons. You do not.

I take that back. You can bash them, who cares what goy gentiles think anyway.

B. Duncan Moench is Tablet’s social critic at large, a Research Fellow at Heterodox Academy’s Segal Center for Academic Pluralism, and a contributing writer at County Highway.