Egon Schiele, Billionaire Ron Lauder’s Boyhood Version of Jimmy Page, Live at the Neue Galerie

A New York show delivers an early incarnation of the hunger artist, fascinated with the malleability of his own body

Our President, Ronald S. Lauder, has enjoyed a lifelong commitment to the art of Egon Schiele. He acquired his first Schiele drawing with his Bar Mitzvah money at age thirteen, and has been under the spell of this artist for almost six decades. —Renée Price, Director, Neue Galerie New York

At age 13, I can’t say I was under the spell of Egon Schiele. But there is no doubt that I was under the spell of the iconic rock guitarist Jimmy Page. The poster of Page that hung on the wall in my bedroom (I’m not sure if I bought it with my bar mitzvah money or not) came to represent my fantasy of embodying a skinny, pale, stringy-haired, rock idol. I kept hearing rumors about Page’s heroin addiction, his alleged communions with Satan, and his supposed pedophiliac tendencies, but nothing could spoil Page for me—nothing could break the spell.

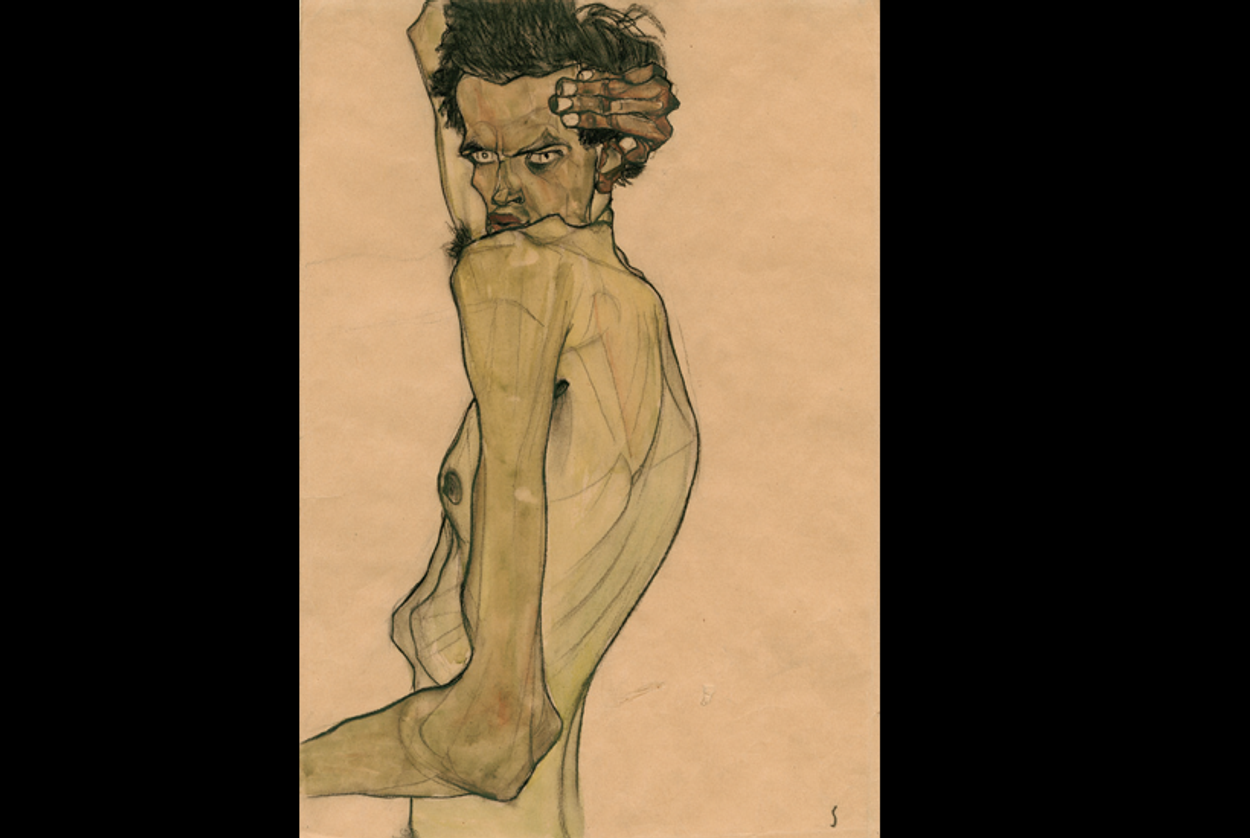

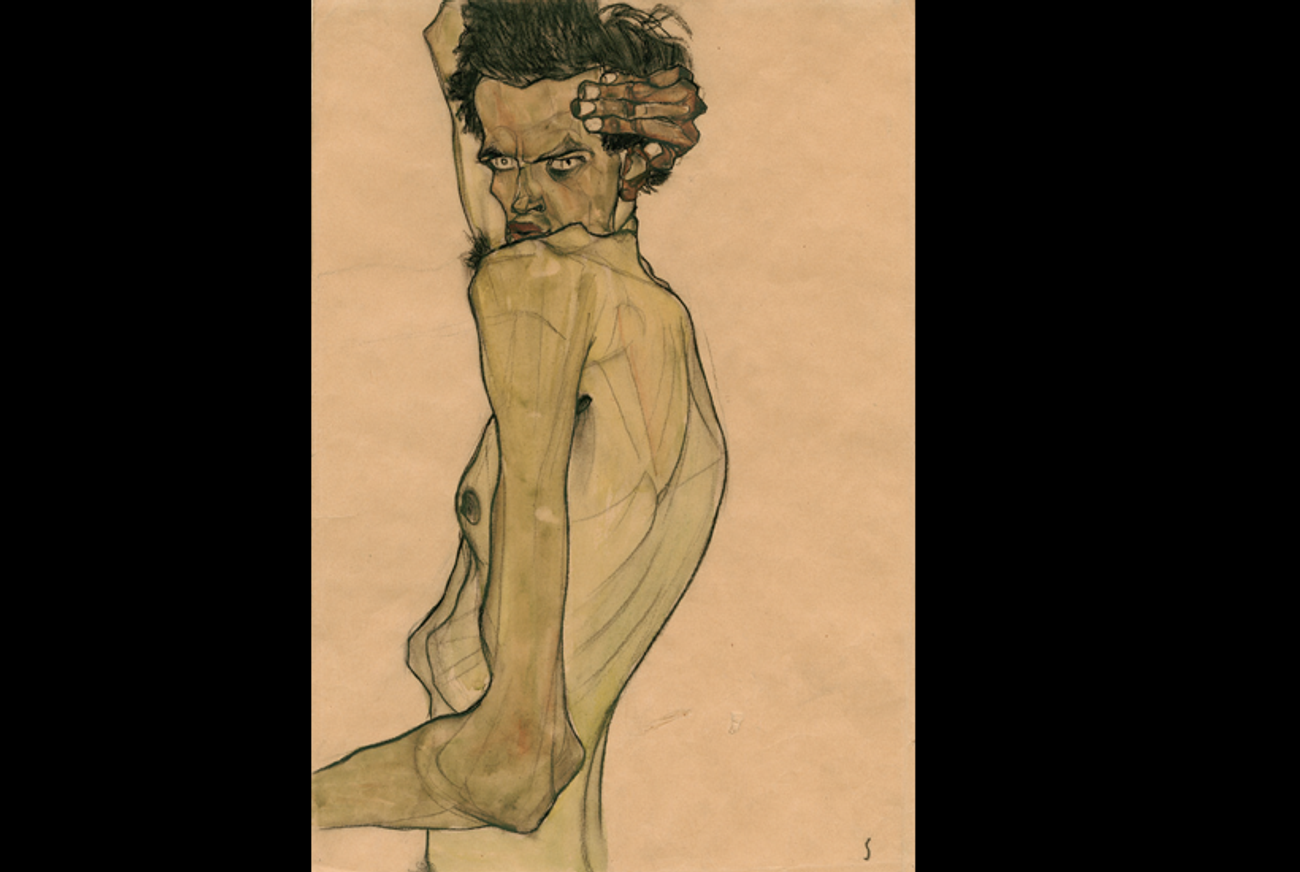

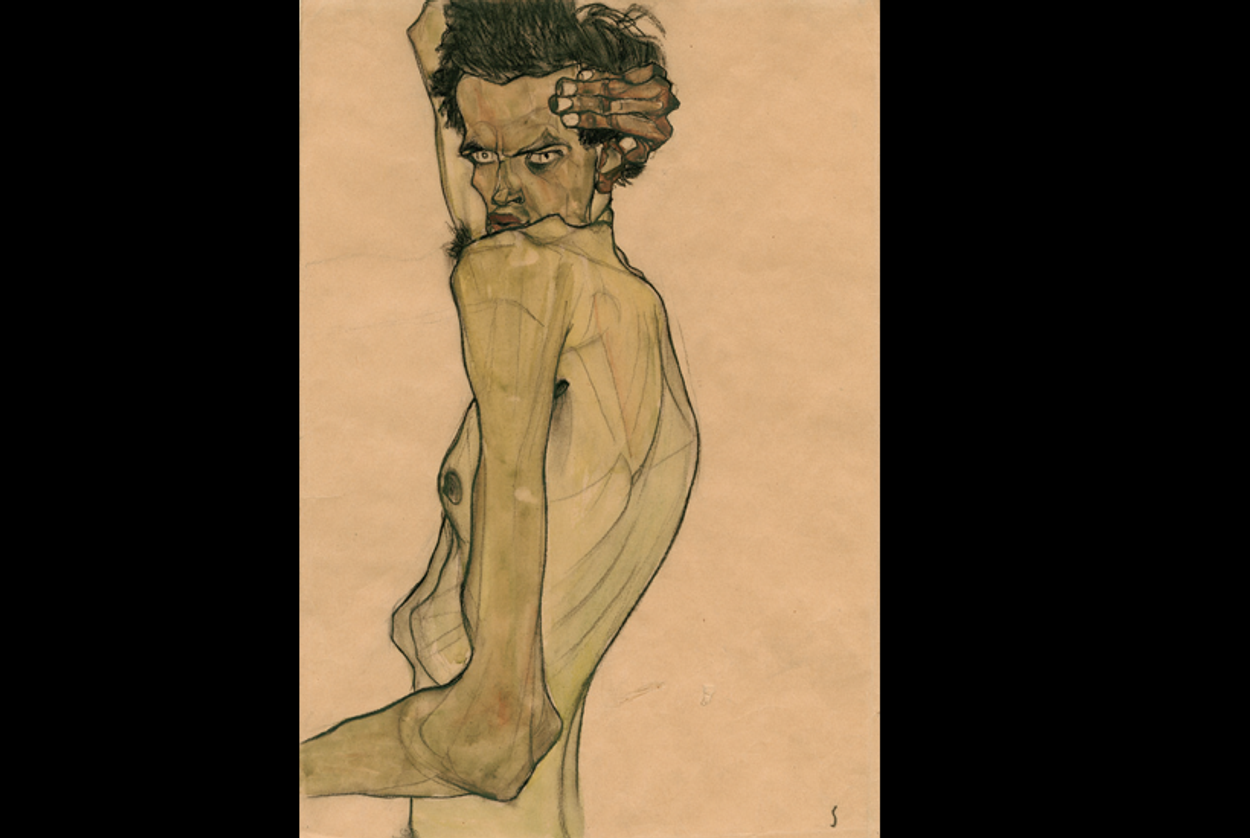

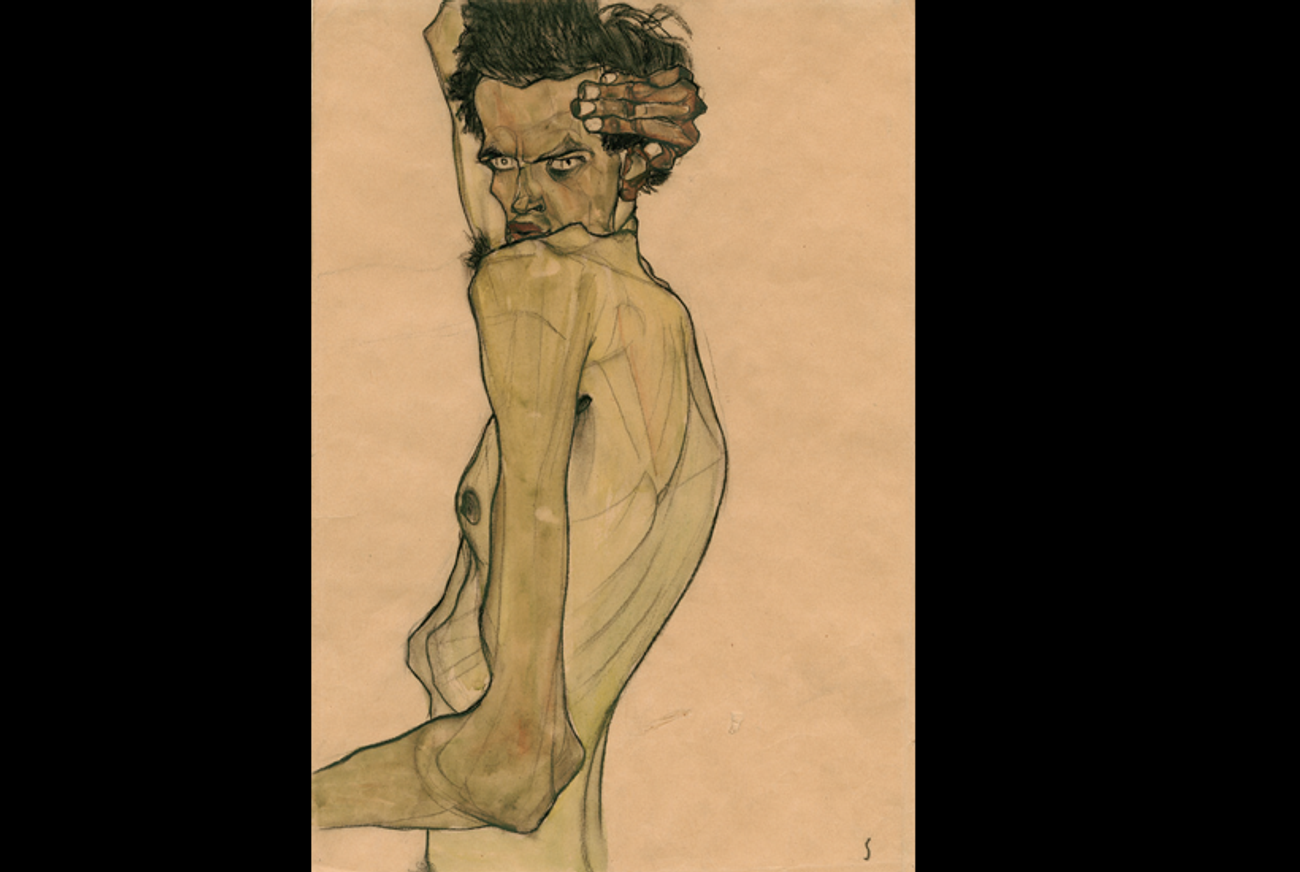

I am tempted to put Schiele and Page in the same “skinny rockstar” camp. But while staring at a 1910 self-portrait featured in the recent Schiele exhibit at the Neue Galerie in New York, it occurred to me that Schiele went beyond depictions of skinniness to explore a far more unsettling extreme: the skeletal.

Skeletal has a dark past. Most of us today can easily visualize emaciated bodies in a heap of corpses in concentration camps. What I find most unfathomable about such Holocaust images is that the piled-up corpses are not merely naked and dead, but are also victims of forced starvation—a triple whammy. Emaciation makes an impression, which echoes today in images of hungry, starving children, or those suffering from the terminal stages of cancer or AIDS.

My personal exposure to the skeletal is full of contradiction. In her Calvin Klein ads from the early 1990s, model Kate Moss came to exemplify “heroin chic.” The dark rings around her eyes and her pallor created the impression of a permanent hangover. The triangular gap between her legs was larger than usual, because the fleshy inner thighs that would ordinarily be filling this void with a plump sense of volume, were gone—starved off. The pelvic region now protruded with boney tension; hips seemed to push out from within as if they would puncture the flesh.

Fashionable emaciation is also key to the appreciation of Ziggy Stardust. In D.A. Pennebaker’s concert film Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, we see David Bowie backstage getting into character. His fangs have been sharpened, his mismatching eyeballs are well dilated with spooky intensity, his eyebrows shaved off, his Alizarin crimson mullet. His cheeks are totally hollow—body-fat appearing to have dipped into the negative. In this 1981 quote, Bowie’s first wife Angela sums up his rigor in achieving this refined skeletal aesthetic:

On stage he was the perfectionist in everything he did. Every song he performed required utmost precision and concentration. … He would lose about 2 lbs in weight for every stage performance … and at the end of the tour he would look emaciated. I cooked nutritious meals for him to regain his energy and proper weight which was around 145 lbs.

My own collection of skeletal imagery also includes Kafka’s 1922 short story “A Hunger Artist.” In it, the protagonist occupies a cage, set up in a public square, where he fasts and puts his malnourished body on display. After about 45 days, the hunger artist, having morphed into a new body—a sculpture—is ripped from the cage by concerned authorities and forced to eat. Mind-over-body is an intensely competitive game, and the mind often wins.

A more contemporary hunger artist—champion of the extreme sport of weight-loss—is Christian Bale, who mastered starvation for a number of recent films. And I have to give credit as well to Matthew McConaughey, who pulled out all the stops in Dallas Buyers Club. Here the actor chats with the press about his methods:

I found tapioca pudding and I found the tiniest little antique spoon in New Orleans, a little bitty sugar spoon, and I would eat it with that so it would last longer. … Oh it was great! I could make it last an hour.

All of these images of “skeletal”—some intentional some unintentional—sprang to mind, as I unpacked “Self-Portrait (With Arm Twisted Above his Head)” from 1910, in which Schiele appears before the mirror. What does the young artist see in his skeletal physique? Is he shocked by his deterioration; panicked by his weakened system; threatened by further sickness; ashamed? Eight years after this portrait was made, the artist, his wife, and their unborn child would all die in the Spanish Flu epidemic, and only a few years before this image was painted, Schiele had experienced his father’s decay from syphilis.

As haunted as this self-portrait may seem, however, the truth is that Schiele at this point was not dying. He was flourishing. So wired with energy and nerve was his work, that today—nearly a hundred years after the fact—the shock waves of a living, breathing creature can be vividly felt. Schiele had a gift in his bursting confidence that led to a remarkably prolific accumulation of works in just 10 years—in the face of increasing scorn from the public. The intensity of his work seems to be stored in his ever-steady barbed line (a manner of life-drawing that he copped off his teacher Gustav Klimt).

Schiele’s accuracy in capturing scale and proportion in perspective with distributed weight and gravity shows that he was and is a true master of the figure. His reclining bodies, no matter age or gender, clothed or naked, exist in an atmosphere that cannot be questioned. Believable depth-of-field is rendered always with minimal description, but with a slight nuance: Schiele tells a long story. What I’m saying is that Schiele could really draw: He had an eye, a touch, and a ruthless drive for perfection.

And while the work, known for its economy of means, is here to be celebrated and enjoyed for the simple fact of its descriptive line, there are many aspects of the Schiele biography that continue to steal away our attention from the works’ pure visuality. Aren’t we bored yet with the story of Schiele’s marginalized bohemian lifestyle, his interest in softcore pornography, masturbation (Wow! Masturbation! No way!), and his over-arching pedophilia? Our maximized mental powers are also put to waste as we contemplate and conjure the young vulnerable sex addict behind bars. Imagine: Egon in Orange Is the New Black.

***

In the late ’90s journalists got hot and bothered and had a field day with a story regarding one of Schiele’s portraits of his star model, Wally. The Jewish family of the rightful owner of Wally’s portrait, Lea Bondi Jaray, had been pursuing the work after it appeared in a show at MoMA in 1998. In an unprecedented move, the New York County District Attorney used his power to issue a subpoena forbidding the painting’s return to Austria. The portrait was then tied up in litigation until 2010, when Austria’s Leopold Museum agreed to pay $19 million to the true owners of the work, in exchange for the painting they already owned.

But before the case had been settled, our previously mentioned bar mitzvah-boy Ronald Lauder himself spoke out, if you can believe it, against the District Attorney and the Jewish family trying to reclaim their Nazi-looted painting, joining MoMA, The Met, and The Guggenheim in their opposition. The museums were adamant that if the painting was not returned to its Austrian lender the all-important future enterprise of exhibiting borrowed paintings with shady provenances would be jeopardized, and the luxurious leisure pursuit of viewing stolen art could suffer a blow. (What will I do all day?) Anyway, watch the documentary, Portrait of Wally (2012). It is, as the kids say, amazeballs.

But the documentary, like the gossip about the artist’s perversions, says nothing about what truly makes Schiele so riveting—namely, his killer, hyper-intense linear ability. I stress this because it is true, and because both stories about looted paintings and louche life choices turn Schiele into a victim; a martyr of his own desire; a man who tasted evil and died of its poison; a man who became contaminated by fin-de-siècle Vienna and experienced the fate of a real-deal “degenerate” prior to the complete Hitlerizing of Europe.

So, let’s take a fresh look at the self-portrait. Pure looking may be enough with Schiele, for there is such mischief and intelligence in this line, and such torque in the bodies, that they never stop speaking. When I gaze at this same 1910 portrait, I now see a man acting, role-playing. Schiele is not sick and suffering. He is searching for the perfectionism of bodily transformation in order to explore a persona and an idealized eroticism. Just like Ziggy Stardust! Perhaps in Schiele, we meet an early incarnation of the performance artist—the hunger artist—who’s medium is the malleability of his own body.

While Schiele distorts the features of his models—elongates arms and legs sometimes to the point of caricature—there is no doubt that he was lucidly aware of these exaggerations. His mind was not playing tricks on him, his perception was not out of whack, as is the mind of the anorexic who cannot get an accurate read from the ever-deforming mirror.

So, why then does this 1910 self-portrait appear to be a poster boy for intravenous drug abuse? Perhaps Egon is not so much acting in his self-portraits, but flaunting. The works are loaded with such conviction that they become entirely believable. Schiele, I like to imagine, is provoking us with his indulgence in the life of a rockstar who cannot hide his bad habits. The more I stare, the more I am convinced that I am seeing the self-portrait of a junkie. A man who stops to look at himself in the mirror amused by the strange animal he sees. He gathers his talent and draws his rotting teeth, blurry gaze, visible ribs, dry mouth, bony hips, protruding pelvis, bruises from needles, skin rashes from incessant scratching. This is more apparent in another self-portrait, “Standing,” also from 1910.

And the hair! In all of Schiele’s work, hair remains a preoccupation, an exaggerated symbol of virility, a mark of Schiele’s nerve. Be it eyelashes or pubic hair, every blade has a spiky threatening quality, that contrasts against the washed-out translucency of skin and garments. Hair, you could say, is where Schiele, the predator, digs in to the flesh and makes his kill. Also, I might add, it is through such bungled patches of hair that Schiele’s sitters are brought even more to life through the implication of scent—the imaginary inclusion of a distinct body odor.

But in my research to substantiate my guess that Schiele was using drugs, I came up with nothing. The closest I got was a portrait he did of Klimt presumably holding an opium pipe. How could Schiele and his posse not be nodding out in a shooting gallery slash art studio?

Indeed there is still one other side to skeletal: health. A balanced diet today means control over all intake and near total abstinence from all solid and liquid contaminants. The healthy skeleton must fast through life. You could say that the lean body at its most efficient maximized state, most athletic—optimized—is only a few pounds away from the malnourished one. I’m reminded of an article I once read about an old lady who lived well into her nineties on just a little piece of chocolate and one cigarette a day. Her skeletal body was not starved, but on the contrary, it was perfectly balanced and sustained. This beautiful woman was just like Egon Schiele; both characters were equally transgressive in obtaining an economy of means.

Schiele put Klimt on a diet. This is why Schiele’s pencil line, all by itself, becomes so pronounced—paint no longer smothers the drawing. Look at the viscosity of Schiele’s paint: Marks often appear greasy and semi-transparent because the pigment has been cut so thin, stretched so far. The smear of the brush—its skid across the dry surface—is starved of actual paint, and large areas of canvas (or paper) are often left naked. But in every finished Schiele without exception nothing is ever left out, nothing ever appears to be done hastily or halfheartedly.

Schiele had to have realized that the paintings exemplified by Klimt were soft. They were built-up with overstuffed beds of color, composed of cushions, daybeds with too many pillows. Paintings denoting luxury and relaxation, they were passive. Schiele wanted to avoid comfort and the compliance that goes along with it. By keeping his work uncomfortable, raw, deprived, his paintings remain desperate to this day—desperate ultimately to communicate with us.

Whether Schiele is seen as an image of total health or total sickness, he embodies a kind of “lean mean fighting machine”—living off just enough to maximize his vibrancy and nerve and to transform desire into art. It is this starved quality that continues to buzz in the work. Schiele is an artist that fully metabolized his world.

In some of his most pornographic drawings, his probing line—with its entrancing conductivity—intersects with the hand-eye coordination of the masturbating model. Conceivably, Schiele’s line explores the paper in synchronicity with the model’s exploring fingers. The tip of the pencil stimulates the work of art just as the tip of the finger stimulates the body. It all happens at once, and so the work powers a circuitry of creative arousal. The work, you could say, is brought closer and closer to orgasm. Focused on just this intense and even more intense rubbing, all else is forgotten. The mind is seized by pleasure. The body is reduced to just nerve endings.

Full circle back to Mr. Lauder’s and my own earliest spellbinding pictures—his Egon Schiele and my Jimmy Page, two mythic characters who were indeed poster boys for an alternative physical body and a divergent path in life. Lauder isn’t interested in Long Island, or Baltimore, split-level basement Led Zep. He paid the big bucks and keeps on paying, where I paid by essentially not getting paid (that’s poetry, as they say). While Schiele and Page may have looked gaunt—demonically so—and both had bad habits and marginal reputations, the reason they matter as much as they do is that they could both really play, and they played their hearts out. And unlike the teenage crush that wears away in no time, these rooted obsessions remain for life.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, My Vibe, was published by Spoonbill Books.

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.