Ralph Waldo Emerson, a Tantalizing, Unsentimental Prophet, Is Miles More American Than Maya Angelou

Just don’t ask him about sex

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“If an inhabitant of another planet should visit the earth, he would receive, on the whole, a truer notion of human life by attending an Italian opera than he would by reading Emerson’s volumes,” John Jay Chapman remarked. “He would learn from the Italian opera that there were two sexes; and this, after all, is probably the fact with which the education of such a stranger ought to begin.” Chapman, a devoted reader of Emerson, was not wrong. Emerson seems willfully ignorant about the torments of love and sex, the pangs of vengeance, the rancor that afflicts the weak, and our sadistic domineering urges. And in Emerson, unlike the opera, no gorgeous women plunge to their deaths.

But Emerson is far from sanitized, upbeat or anodyne. He is a tough, tantalizing prophet of the American self. James Marcus’ new biography, Glad to the Brink of Fear: A Portrait of Ralph Waldo Emerson, gives the best picture yet of Emerson—this country’s key thinker—whose writings try to answer, more than any others, the question of what it means to be an American.

The late-19th-century frontier household was sure to have a well-worn copy of the Bible and often a Farmer’s Almanac. Next up in popularity was a volume of Emerson’s essays. Emerson urged Americans to practice self-reliance, pull themselves up by their bootstraps, see the auspicious possibility in the rough-and-tumble facts of experience. He was a secular preacher, urging us to follow our own genius wherever it might lead.

Along with Frederick Douglass, Emerson was the most popular lecturer in antebellum America. Somewhat stiff on the podium, the wiry-looking Emerson in his black suit resembled a “perpendicular coffin,” the humorist Artemus Ward joshed. But when he started to speak, the audience was spellbound. One awestruck anonymous reviewer said that Emerson “let off mental skyrockets and fireworks.” He gave nearly 1,500 lectures over 50 years.

Nowadays, I reliably find that none of my students has read an Emerson essay in high school. Maya Angelou has replaced him as the canonical American author of nonfiction prose, according to the political criteria favored by our grade schools. (It’s fine for Angelou to be read in schools. But to read her instead of Melville, Whitman, Douglass, Cather, Hurston or Emerson replaces literary sublimity with sentimental tokenism.) When students finally encounter an Emerson essay, which is increasingly unlikely in college classrooms as well, they are shocked and pleased, and ready to meet him on his terms.

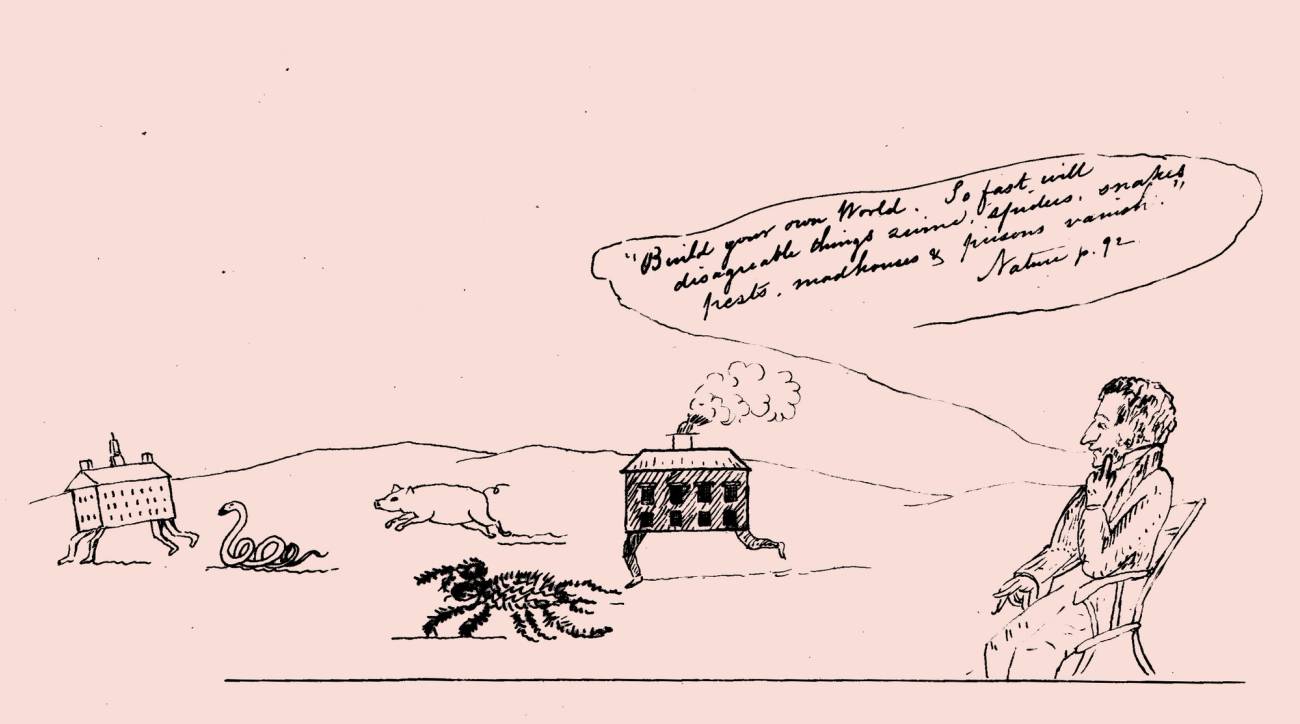

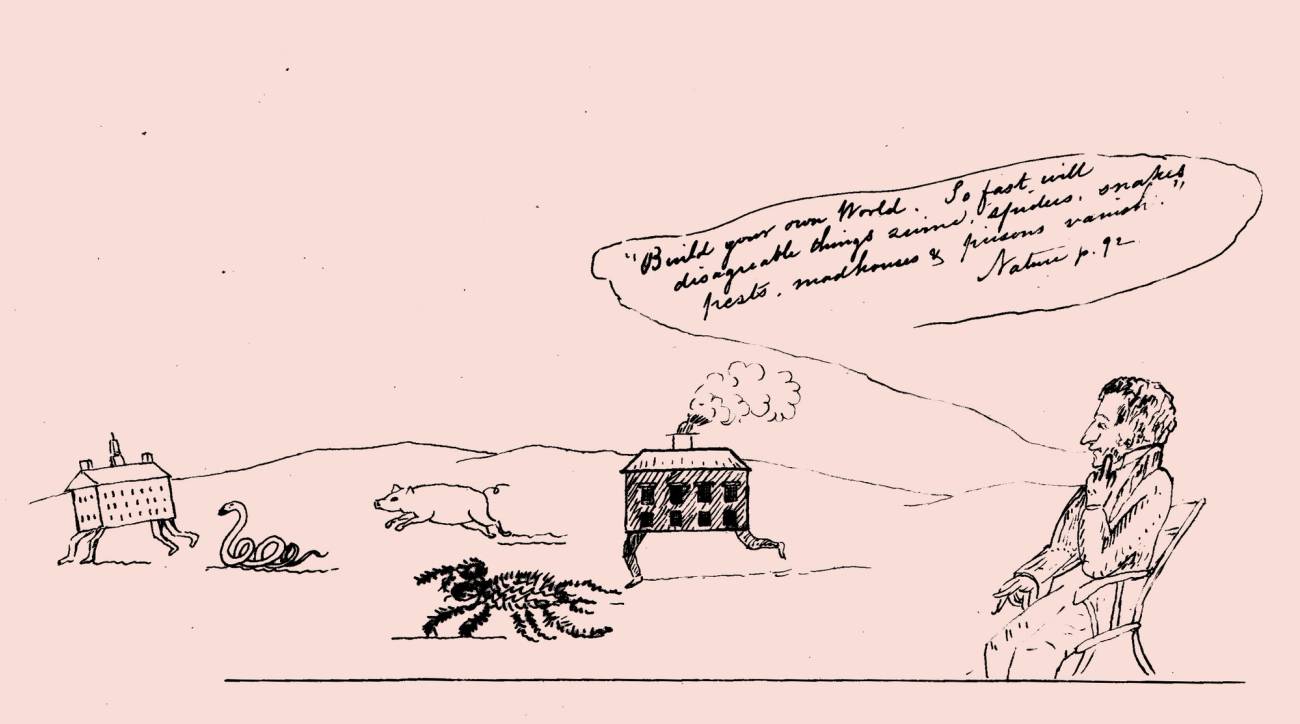

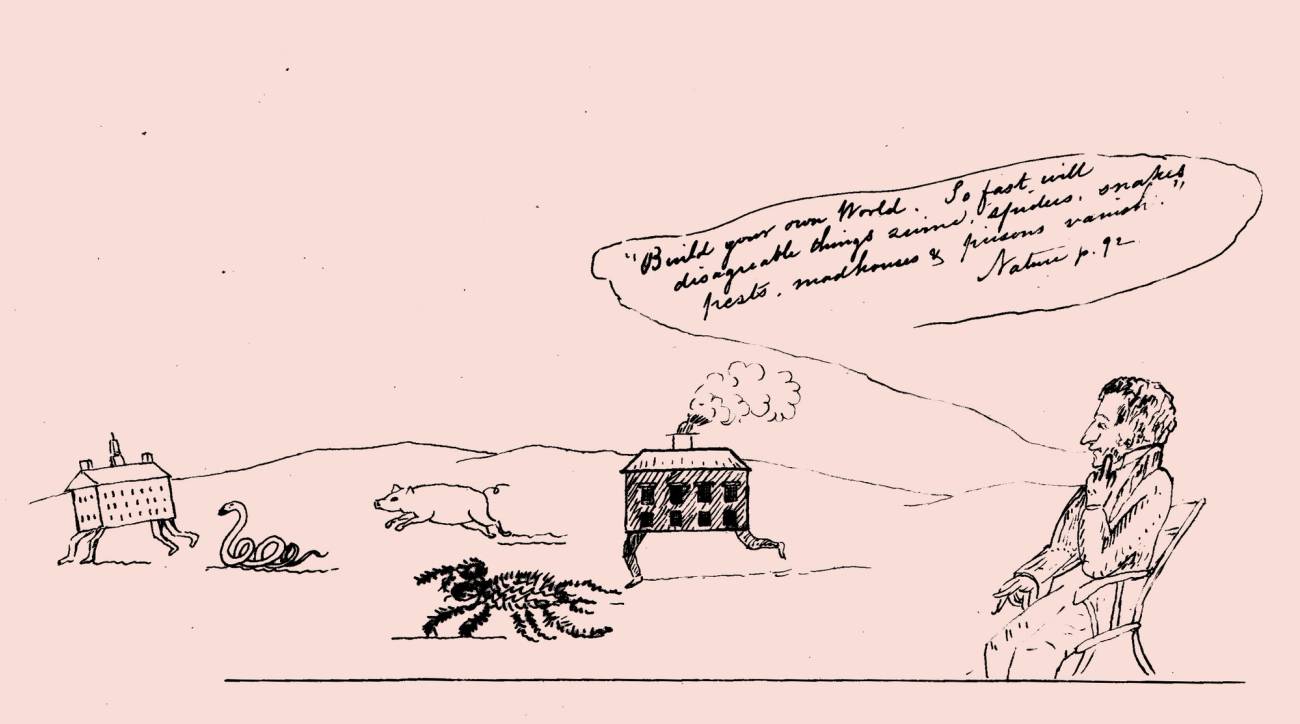

Emerson’s provocations begin with his daring aphoristic prose, which shakes you loose from your moorings. Moving from one Emersonian sentence to the next can feel like crossing a stream on “th’unsteadfast footing of a spear,” as Shakespeare’s Worcester says in Henry IV. Consider a few lines from Emerson’s early book Nature:

A man is a god in ruins. When men are innocent, life shall be longer, and shall pass into the immortal, as gently as we awake from dreams. Now, the world would be insane and rabid, if these disorganizations should last for hundreds of years. It is kept in check by death and infancy. Infancy is the perpetual messiah, which comes into the arms of fallen men, and pleads with them to return to paradise.

First Emerson thrusts out with a memorable aphorism. We are ruined gods, like Milton’s Satan, for whom there was no route back to paradise—but there can be for us. “Life shall be longer” is lulling and ordinary, but rises softly into a promise of immortality. Then Emerson rudely retracts such Edenic tones, telling his readers that if “these disorganizations”—a disturbing, at once dodgy and evocative way of describing our lives—lasted for centuries, we would inhabit a savage world, “insane and rabid.” All that saves us is death, and more to the messianic point, the infancy that “pleads with” us to come back to a possible paradise. Every baby is a messenger who could save us. Emerson dips down low, then scales a high peak, the Romantic hope that a childlike eye points toward holiness.

Emerson urged us to read for the lustres, the shining patches of brilliance that adorn a literary work. His work has an abundance of those, but he also delivers a sustained case for aspiration. He wanted us to look at everything with new eyes, as if the world had just been created. But we are not “tuned up to concert pitch our whole lives,” as Marcus admits, and so the awakening Emerson urges frequently passes us by. When it does hit us, it remains inside the sole self. “His ecstasies were internal,” Marcus comments, unlike the crowd-thrilling convulsions offered by the Second Great Awakening’s aroused prophets.

The late-19th-century frontier household was sure to have a well-worn copy of the Bible and often a Farmer’s Almanac. Next up in popularity was a volume of Emerson’s essays.

There have been plenty of slurs aimed at Emerson. We’ve been told he avoids life’s troubles, specializes in vague mystical consolations, that his prose is an unstructured, starry-eyed mush. None of this is true. Emerson in fact mocked the New England Transcendentalists for their lack of realism. (Transcendentalist was a “jeering nickname,” Marcus notes, applied to those who had imbibed too much German metaphysics.) Emerson was hard-edged, cognizant of tough facts. In “Fate,” which like “Self-Reliance” and “Experience” is one of his essential essays, he writes, “We must see that the world is rough and surly, and will not mind drowning a man or a woman; but swallows your ship like a grain of dust ... The diseases, the elements, fortune, gravity, lightning, respect no persons.”

Emerson confronted the abyss of skepticism in “Experience,” which remains one of the glories of American writing. He wrote the essay just a few years after the loss of his beloved son, little Waldo, “the world’s wonderful child, for never in my own or another family have I seen anything comparable,” as Emerson wrote to his Aunt Mary. “Experience” begins in a daze, with the shimmering aura of life’s unreality lingering like an opiated hangover. “All things swim and glitter. Our life is not so much threatened as our perception,” Emerson remarks. “Ghostlike we glide through nature, and should not know our place again.” Even more than elsewhere, Emerson in this essay conveys what Marcus calls his “elation and puzzlement and playfulness, and also the communion: the eerie sense that he is speaking to you and through you,” as well as a strange sadness about human existence.

By temperament, Marcus explains, Emerson was far from an evangelical. Yet he was as eager for revelation as any hot-blooded revival preacher. Divinity is hidden in the most ordinary corners of the world, he urged. “What would we know the meaning of? the meal in the firkin; the meal in the pan; the ballad in the street; the news of the boat; the glance of the eye; the form and gait of the body,” he wrote in “The American Scholar.” His wish to be jolted by experience differs from Wordsworth’s more analytic, heart-scrutinizing Romanticism, which turned Emerson off.

Emerson graduated Harvard in 1821. He felt, he said, “a sore uneasiness in the company of most men and women.” He became a minister, his father’s profession, but was awkward when visiting bedsides and bereaved families. “What is called a warm heart, I have not,” he admitted.

In 1832 Emerson stopped being the pastor of the Unitarian Second Church, located in Boston’s North End, near saloons and brothels. This was in part an effort to stir himself up to greater passion: He sneered at “the corpse-cold Unitarianism of Brattle Street and Harvard College.” He became a freelance preacher, and eventually a hugely busy lecturer on the Lyceum circuit, enduring many a rough train journey to hardscrabble towns in the Midwest. During a stop in Belvidere, Illinois, he noted, “Winter in Illinois has a long whip. To cuddle into bed is the only refuge in these towns.” It was the 12th day of a cold snap, and 22 degrees below zero.

Emerson’s first wife, Ellen Tucker (who was “smart, silly, immersed in books,” Marcus says), died from consumption in 1831. So did Emerson’s brother Edward, in 1836, and then little Waldo, at age 5, in 1842. His second wife, Lidian, had a passion for animal rights, encompassing even flies, wasps, and spiders, but she balanced her idealist fads with a healthy sarcasm. She lampooned her husband’s lofty ardor in a pamphlet she wrote called the “Transcendental Bible”: “Loathe and shun the sick. They are in bad taste, and may untune us for writing the poem floating through our mind.” She added, “Spare me from magnificent souls ... I like a small common-sized one.”

‘All things swim and glitter. Our life is not so much threatened as our perception.’

Marcus’ book is not perfect. Sharing the prejudices of coastal liberals, he sometimes writes superficially. Apropos of nothing, he calls resistance to masking during the COVID era a “national neurosis.” Yet masking toddlers, for no scientific reason and in contrast to European practice, is exactly the sort of mindless conformity that Emerson detested. Marcus’ deference to received ideas hardly accords with what he calls Emerson’s “vision of the individual as limitless, held back only by fear, stupidity, caution, custom, tribal deference.”

Glad to the Brink of Fear manifests a disease of our time: being gravely, solemnly, performatively disappointed when some figure from the past fails to share every single one of our current opinions, like good little mannequins. Marcus indulges in endless hand-wringing over the traces of prejudice he finds in his hero. Emerson was too slow to come to the anti-slavery cause, Marcus charges (he waited until 1847). The abolitionists, some of whom wanted to secede from the Union, seemed to him fanatics with little sense of political reality. But when he came in, he came in big, denouncing the “greatest calamity in the universe, negro slavery.”

Marcus quotes Emerson’s fiery sentences from his 1848 essay on the emancipation of slaves in the British West Indies. This new freedom, Emerson announced, meant “the annihilation of the old indecent nonsense about the nature of the negro.” “The might and right are here,” he wrote. “Here is the anti-slave: here is man: and if you have man, black or white is an insignificance.” These lines, and others like them, ought to be sufficient to prove Emerson’s anti-slavery credentials.

Adhering to the needs of present-day progressivism, Marcus requires a straight-faced, unblinking piety that, thankfully, Emerson refuses to supply. “I wish Waldo hadn’t found the activists of his age so comical,” Marcus moans. But they were, and Emerson would have been a fool not to discern the crackpot side of the trendy causes that swirled around him. In “New England Reformers” he describes the activists who “made unleavened bread, and were foes to the death to fermentation.” Then there were “the adepts of homœopathy, of hydropathy, of mesmerism, of phrenology.” In “New England Reformers,” Emerson complains that “a restless, prying, conscientious criticism” has taken the place of true self-renewal among the social justice warriors of his day. Marcus sometimes exhibits these same carping traits. Tiresomely, he worries that Emerson was just a little too fond of capitalism in his English Traits.

Despite his cramped gestures toward political correctness, Marcus gives the best portrait of Emerson we have, along with Robert Richardson’s classic Emerson: The Mind on Fire. Unlike his subject, Marcus is no bold taboo-breaker, and his style, at times, can be breezy and annoying (Emerson’s detractors, he tells us, dislike his “high cholesterol” prose, with its “empty calories”). He is more often eloquent and moving in his effort to get as close as he can to Emerson the human being. He gets closer than Richardson, who is admirable on Emerson’s intellectual sources, but who doesn’t peer into the crannies of his life the way Marcus does.

Marcus is excellent on the falling out between Emerson and his disciple Thoreau, who wrote in 1849, “While my friend was my friend he flattered me, and I never heard the truth from him, but when he became my enemy he shot it to me on a poisoned arrow.” And this biography gives us many a piquant detail, like a 13-year-old Teddy Roosevelt rowing Emerson and his daughter Ellen to lunch on the Nile during their trip to Egypt in 1873. The future Rough Rider and president was a “handsome boy, though plain,” with “round red cheeks,” “honest blue eyes, and perfectly brilliant teeth,” Ellen noted.

Marcus also wonderfully describes Achille Murat, Napoleon’s 26-year-old nephew, a flamboyant atheist who befriended Emerson during a youthful voyage to Florida. The colorful Murat “slept on a rough mattress filled with Spanish moss and dined on turkey vulture, owl, crow, lizard, alligator and the occasional rattlesnake,” Marcus tells us. For Emerson, atheism just didn’t compute—he was never tempted by its sheer nullity. Yet Murat, who spurned all moral laws, entranced him. The two still remained polar opposites. During his time with Murat, the 23-year-old Emerson was stung by conscience when he witnessed a Florida slave auction. Horrified, he heard the auctioneer’s voice (“four children without the mother”) coming from the yard next door to the Bible Society meeting he was attending.

Emerson has his limits. Nietzsche, who read Emerson with admiration, encompasses much more than the sage of Concord. If you are looking for wisdom about erotic longing, or about the chasm between what we say and what we do, or the myriad ways we trick ourselves into belief—in other words, all our tawdry-yet-vital human perversity—you need to read Nietzsche, not Emerson. Emerson, who seems to have had a few unfulfilled platonic crushes with female disciples, appears vaguely baffled by sexual desire, on the rare occasions when it surfaces in his prose. There is a high-starched-collar doctor-of-divinity side to his persona, which never gets down and dirty with humans at their frequent worst. He wants to think the best of us, an endearing American trait, but this sunny hippie-ish vibe can be wearying.

Yet Emerson is always ready to snap back at us the moment we type him as a cheerful saint. After little Waldo’s body was moved to Sleepy Hollow cemetery in 1857, Emerson opened the grave to gaze at his dead son, as he had earlier opened the grave of his first wife. Emerson knew all too well what Marcus calls “the slow-acting drug of disappointment.” When the universe thwarts us, crushing our spirits like a juggernaut, Emerson sees and feels the defeat. Yet, he keeps insisting, we are born for nothing else but victory. What could be more American?

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.