Eschatologist

Jacob Taubes, a leading midcentury Jewish intellectual, wrestled with the weightiest questions of religion and politics

In 1947, Jacob Taubes arrived at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York as a 24-year-old Orthodox rabbi with a newly minted doctorate in philosophy from Zurich and a wildly self-assured sense that he had begun to solve the mystery of Western culture. His first book, Occidental Eschatology—a sweeping study of the influence of messianic ideas from biblical to modern times, written in German—had just been published and promised to explain nothing less than the “essence of history” and chart “the entire span of Western existence.” As a scholar of Judaism and Christianity, Taubes dealt only with the most provocative and weightiest of questions, which made him an unbearable egotist but also one of the most fascinating thinkers in mid-century Jewish intellectual life. Occidental Eschatology has finally been published in English last year; this year, a collection of his essays on modern religion has appeared under the title From Cult to Culture.

The son of a prestigious rabbi, Taubes was born in 1923 in Vienna but survived World War II in neutral Switzerland. There, he obtained his rabbinic ordination while completing his doctorate and attending the lectures of a famous Swiss Catholic theologian. But he had little desire to stay for long in a Europe drained of many of its best scholars and students. In the United States of the late 1940s and 1950s, he encountered a post-Holocaust generation of Jewish-born American intellectuals newly preoccupied with European ideas and craving reconnection with a lost Jewish tradition. For them, Taubes was a revelation, a youthful embodiment of the world of their fathers. He taught Talmud to the likes of Daniel Bell and Irving Kristol in New York and enraptured a young Susan Sontag with his Harvard lectures on how Christian ideas had been secularized and still determined the course of Western thinking.

Many of the students who wandered into Taubes’ orbit describe, in addition to his erudition, an uncanny and disturbing sexual power. “He was thin and short with a sallow complexion … seldom entirely clear of pimples,” the post-Holocaust theologian Richard Rubinstein remembered of his first Talmud teacher, “fascinating to a certain class of overly cultivated women who were perhaps more interested in exploring the hidden, the unusual, and the mysterious than in openly celebrating the uncomplicated joys of physical love.” Taubes’ appeal, it seems—both intellectual and sexual—lay in his willingness to cross boundaries. He was known to arrive to synagogue in an ostentatiously large prayer shawl and yet to speak constantly of the value of transgressing Jewish law.

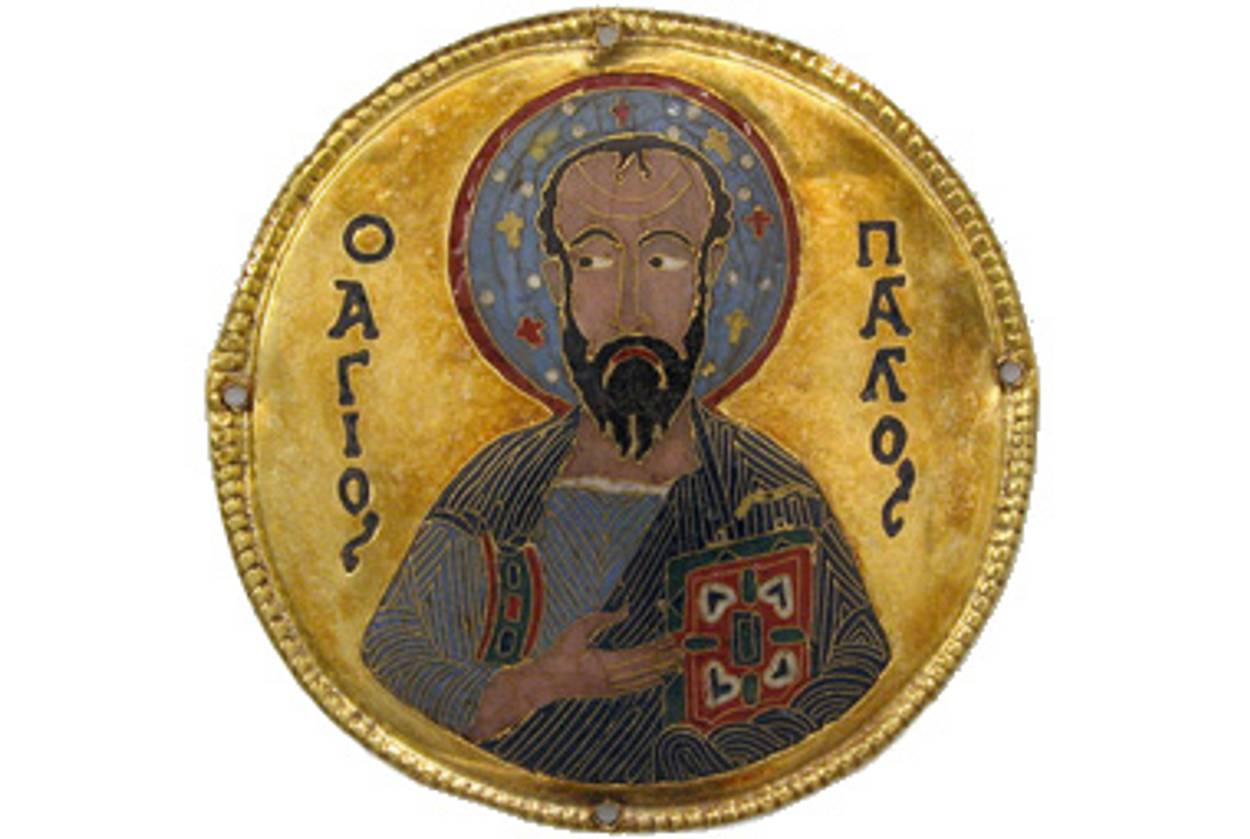

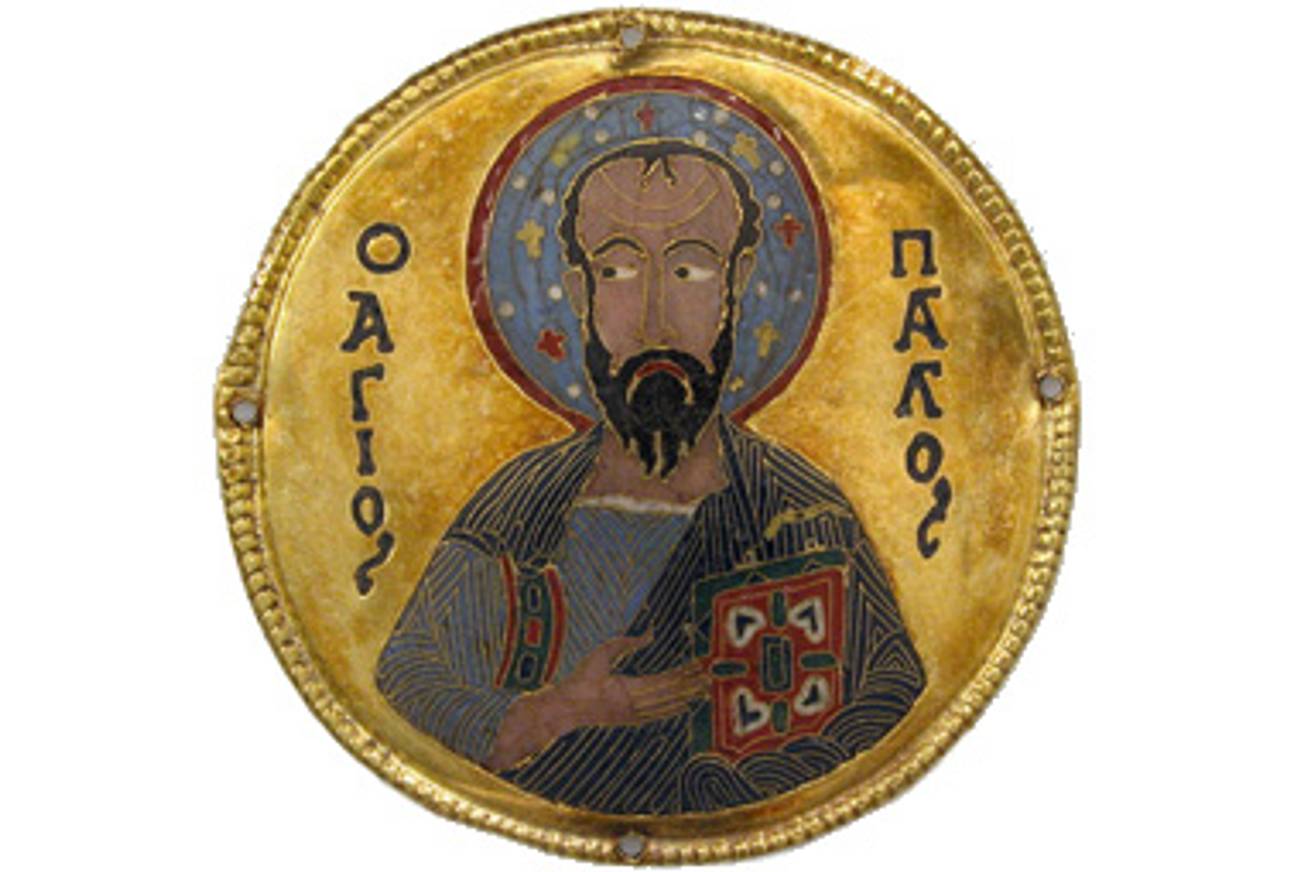

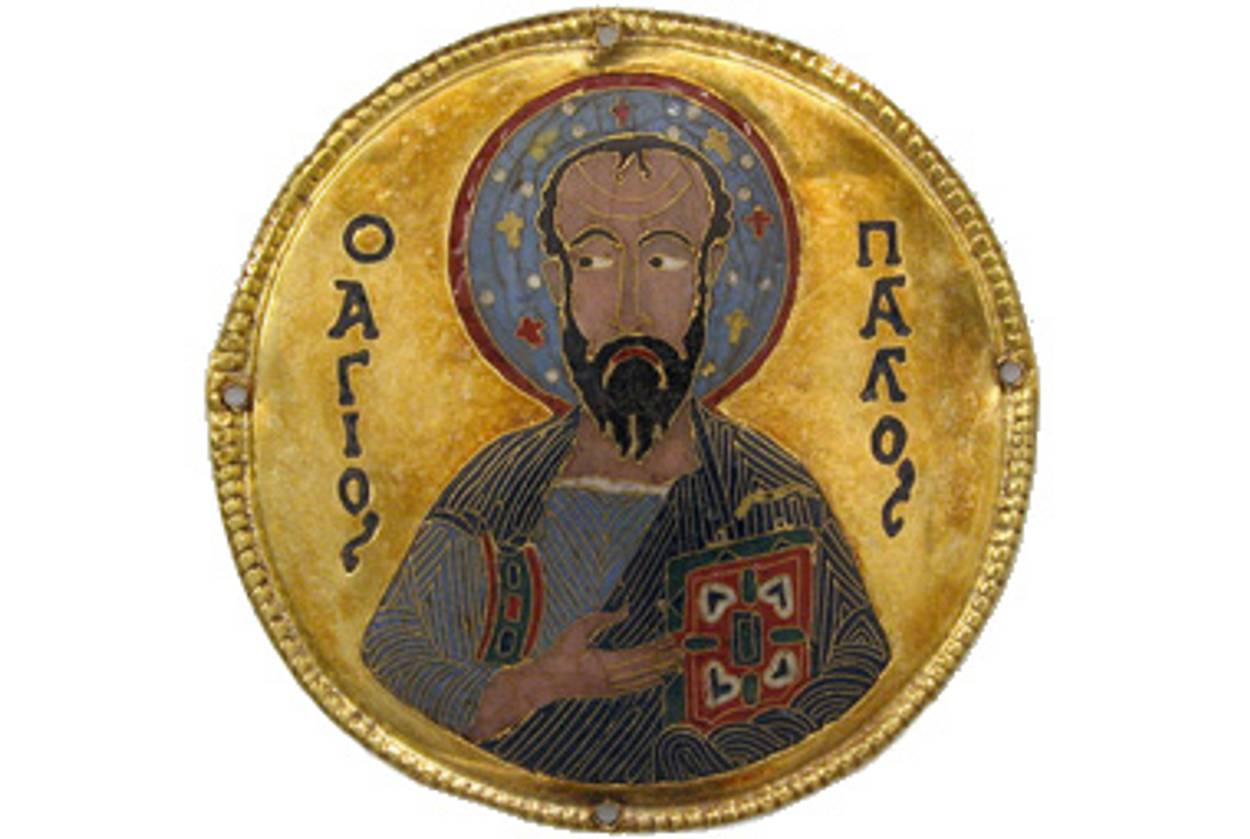

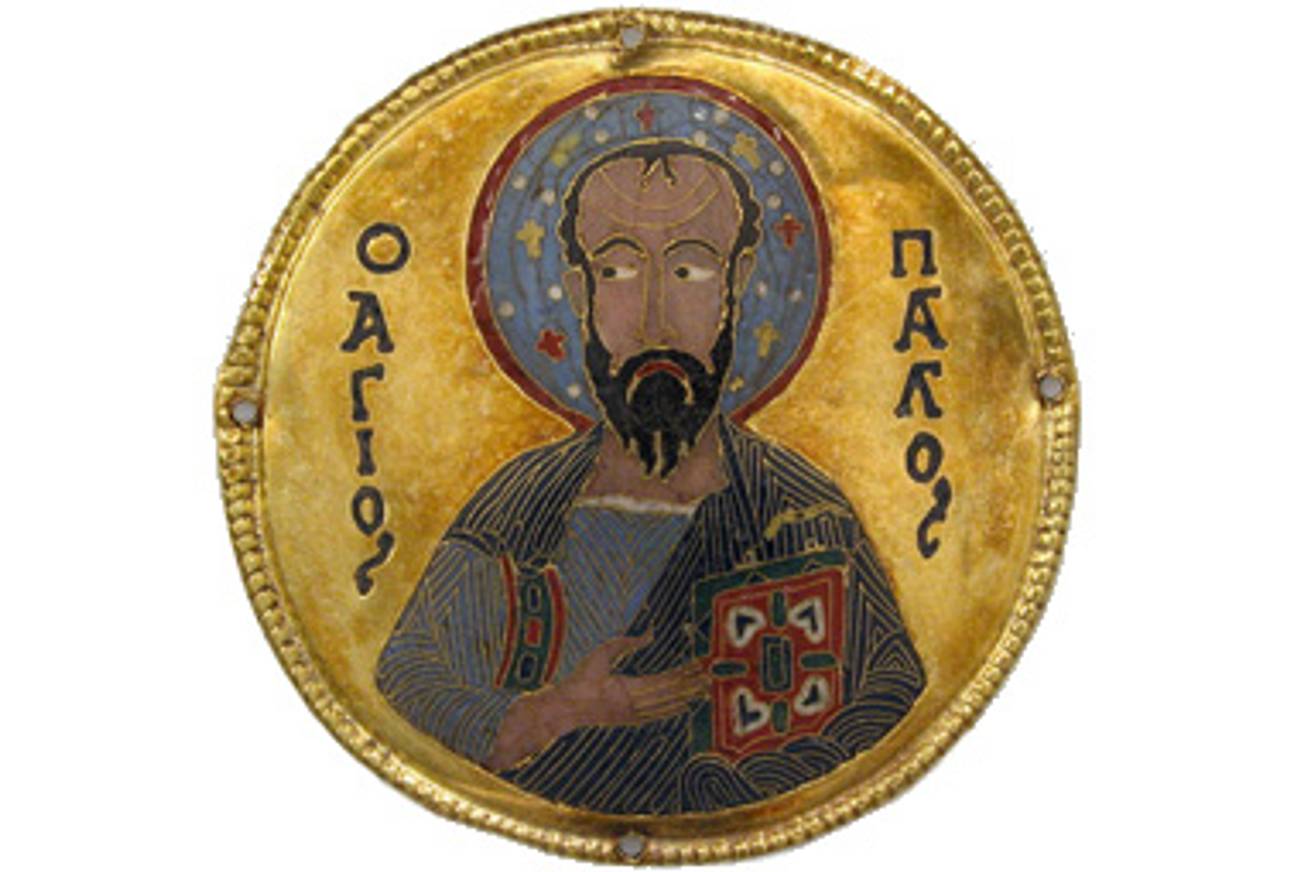

Perhaps it was Taubes’ fascination with deviance that led his work time and again to the apostle Paul of Tarsus—that most famous of historical Jewish transgressors. It becomes clear as one reads Occidental Eschatology and From Cult to Culture that the apostle Paul was never far from Taubes’ mind, even when he wrote on such seemingly far afield subjects as surrealism and psychoanalysis. It was in Paul that Taubes believed he had found the key to the mystery of Western culture. And as he aged, Taubes grew closer and closer to the image of Paul he was creating in his scholarship. His version naturally did not correspond to the Christian interpretation; for him, Paul was not the first Christian but a radical and “zealous Jew,” or, as Taubes once said, an “arch-Jew.”

At first glance, Taubes’ Paul was not so radically dissimilar to our received image of the apostle. Paul was still the same Pharisee who initially condemned the Jesus cult only to do an about-face, rejecting the Mosaic law he knew so well and going on to found congregations of Jesus-followers around the Mediterranean world in the expectation that end-times were near. Taubes asked what remained Jewish in Paul after his turn. His messianism was clearly of Judaic origin, but what about the law? Traditionally, Paul is regarded as the figure who replaced law with faith, circumcision of the body with circumcision of the soul. But according to Taubes, it was crucial that Paul considered faith not only the annulment but also the fulfillment of Mosaic law; Paul believed that faith grew naturally out of the Mosaic tradition as its self-cancellation and that it was in fact unnatural for the message of the fulfillment of the law to be extended to non-Jews. In this reading, Paul was a messianic zealot for the law, an evangelical Jew.

This arguably had political consequences. “The horns of the dilemma cannot be escaped,” Taubes wrote in 1979. “Either messianism is nonsense, and dangerous nonsense at that,” or it “is meaningful inasmuch as it discloses a significant facet of human experience.” He fleshed out what that facet might be in what he called his “intellectual testament,” a series of lectures on Paul he gave in Heidelberg just months before his death in 1987. (He had taught in Germany since the 1960s.) It seems to have been important for Taubes that he delivered his testament to a German audience, not only so he could speak in his mother tongue but because he felt that a long history of Paul misinterpretation had encouraged disastrous consequences in that country when religious prejudice was translated into political practice. The transcript of these lectures was published in English as The Political Theology of Paul in 2004, and since then Taubes’ Jewish version of the apostle has been receiving some long-overdue attention.

There, he discussed the Jewishness of Paul’s Letter to the Romans in particular. Unlike the other epistles (to the Galatians, the Ephesians, and Corinthians, for instance), the letter to the Romans was addressed to a congregation of Jesus-followers composed of both Jews and gentiles and situated in the capital of the Roman Empire. When Paul wrote to them and told them to abandon “the law” (nomos), Taubes argued, he was undermining not only the authority of halacha but of the Roman state, whose law gentiles considered divinely ordained through the emperor, a representative of the gods on earth. In that sense, Taubes said, “the Epistle to the Romans is a political theology, a political declaration of war on the Caesar.” And it was a Jewish political declaration of war because it held a universal law higher than the arbitrary dictates of an emperor who claimed to be a god.

Taubes’ reading of Paul was undeniably shaped by the experience of National Socialism and by his lifelong bid to outsmart Carl Schmitt, the jurist who had presided over Nazi legal theory from 1933 to 1936 and who Taubes told students at the outset of the Heidelberg lectures was “the greatest state law theorist of our time.” This praise must not be misunderstood. On his sole meeting with the former Nazi in 1979, Taubes said that he and Schmitt were “opponents to the death” but got along “splendidly” because they were at least “speaking on the same plane.” That plane was “political theology”—a phrase Schmitt coined to argue that all theological metaphors have political implications, just as all legal orders are underpinned by articles of faith. During their visit, the two men sat down as a hevruta, a pair engaged in study, and read Romans chapters nine through eleven, the passages in which Paul addresses most explicitly the relationship of the Jesus-followers to the Jews who remain faithful to the old law. Schmitt made his career with the Nazis based on the argument, in no small part inspired by a Catholic version of the apostle as enemy of the Jews, that there were no legitimate legal orders that a God-like leader, in whom the people had faith, could not legitimately violate. Taubes suggested that he won the argument with Schmitt—“He always won,” Susan Taubes wrote of her ex-husband in her autobiographical novel Divorcing—but we will never be sure, because no transcript of the conversation exists.

Taubes’ engagement with the politics of theology has bothered some liberals who want to keep the two realms hermetically sealed off from one another. In a rather blithe review of recent Paul literature in the New York Review of Books, for instance, Mark Lilla blames Taubes for kashering thinkers such as Schmitt for left-wing German students in the 1960s and ’70s. Were he alive today, Taubes would most likely respond that if we banned all thinkers who saw a link between theology and politics, we would have to cut out most of the Western canon in our core-curriculum courses. If Taubes bequeathed anything in his intellectual testament, it was not the value of Schmitt but the redemptive potential inherent in the work of Sigmund Freud—the only person Taubes explicitly called a “direct descendent of Paul.” Freud’s psychoanalysis, he argued, self-consciously carried on the Jewish Pauline legacy by demonstrating the universal forces of guilt and repression at work in both Mosaic law and the laws of “bourgeois custom.”

For Taubes, being a Pauline Jew meant being a fanatic universalist. This did not mean trying to translate religious ideals into good government but rather preserving religiously inspired universalism as a realm of constant critique of authority. With any luck, the new English translations of his work will reignite some of the excitement that Taubes originally provoked when he arrived on America’s shores at a time when one’s relationship to Judaism was an existential matter of political principle.

Noah B. Strote is a doctoral student in history at the University of California, Berkeley, where he is completing a study titled The Returns of Exile: German Emigrés and the Creation of West Germany, 1933-1960.

Noah B. Strote is a doctoral student in history at the University of California, Berkeley, where he is completing a study titled The Returns of Exile: German Emigrés and the Creation of West Germany, 1933-1960.