“Some of us are not Jews.” So ran the first sentence of a glowing March 6, 1977, review of John Cheever’s novel Falconer by Joan Didion on the front page of The New York Times Book Review, an article that lamented the “homelessness” of the “white middle-class Protestant writer” in America and went on to critique as woefully misguided an analysis of a Cheever short story, “The Country Husband,” by Alfred Kazin. Didion calls Kazin’s comments a “deflationary reduction” (although Kazin had characterized the story as “brilliant”), but the implication was obvious—namely, that Jewish literary critics such as Kazin were deaf to Cheever’s singular accomplishments and had been responsible for Cheever’s relatively low repute in the literary world.

Unsurprisingly, Kazin responded in an aggrieved letter to the editor, pointing out that he had spent his entire career as a critic writing almost entirely about non-Jewish writers. Didion responded with the cool terseness for which she was celebrated: “Oh, come off it, Alfred.”

Didion’s review is nowhere cited in Josh Lambert’s The Literary Mafia: Jews, Publishing, and Postwar American Literature, but her basic proposition is everywhere affirmed in its pages. Although Lambert repeatedly disavows the idea of a Jewish mafia, calling the notion “false and even pernicious,” that term forms the title of his book and the title of his conclusion in which he welcomes the dominance of other ethnic groups in publishing (“We Need More Literary Mafias.”) Moreover, the book’s central argument is that Jews shaped postwar American literature through a tacit, unstated, and often unfair system of influence in which Jewish agents, editors, intellectuals, academics, and writers promoted other Jews. Lambert variously calls this system a “network,” an “ethnic niche,” “a system that has privileged” Jews, a sphere of “privileged access,” “consequential gate-keeping roles,” and “positions of influence and power.” The Literary Mafia is offered as a work of Jewish Studies (Lambert is an associate professor of Jewish Studies and English at Wellesley College), but it also has an evident theoretical foundation in the work of the French social theorist Pierre Bourdieu, famous for his idea of “cultural capital,” a debt buried in a footnote. Yet Lambert’s book represents a crude misapplication of Bourdieu’s influential ideas about “fields of influence” as Lambert tries to export them to the New York publishing sphere.

The Literary Mafia is not a book about Jewish cultural accomplishment or the Jewish love of learning or even about how the People of the Book—openly discriminated against in American higher education and effectively barred from tenure at America’s most prestigious universities—gained a foothold in the New York book industry. Like other conspiracy-laden critiques about Jews, from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion to the recent rants of Viktor Orbán, The Literary Mafia is about perceived Jewish power—the rule being that the presence of more than one Jew in a room demonstrates the existence of a malign Jewish cabal.

Yet even if Lambert’s questionable contention about Jews dominating American publishing were true, it is baffling why Lambert would choose to deploy the word mafia—which denotes, of course, a tightly knit criminal organization that murders people. In 1974, as Lambert points out, Richard Kostelanetz referred to a Jewish “mob” overseeing New York publishing in a much-derided essay, a view shared by Truman Capote, Jack Kerouac, and Katherine Anne Porter. Lambert manages to outdo the unpleasant accusation of that disgruntled cohort by going on to state that “Jews were also for the most part complicit in the U.S. publishing industry’s and literary field’s misogyny and white supremacy …”

Get it? Jews were not only “complicit” in discrimination against women and African Americans but in a hatred of women and in a belief that white people are inherently superior to black people. So that’s what they were up to, all those evil Jewish literary mafiosi—like Robert Bernstein, President of Random House, who hired Toni Morrison and then arranged for her novels to be published at Knopf in order to fasten his white supremacist claws ever-deeper into the flesh of virtuous African American womanhood. … Yeesh.

The Literary Mafia keeps pushing the funny idea that postwar American literary Jews all identified as Jewish, wanted to be seen as Jewish, identified with other Jews, wished other Jews to succeed and, because of these identifications, chose to advocate for the professional aspirations of their Jewish brethren. There are pages and pages in Lambert’s book on Lionel Trilling (whose attitude about his own Jewishness is a much-debated subject among critics and biographers) that laboriously try to demonstrate that Trilling favored his Jewish students. But there is just as much, if not more, evidence to suggest that Jewish editors, teachers, publishers, and critics competed with, disfavored, ignored, or tried to undermine other Jews. The examples are everywhere: Norman Mailer dismissed the fiction of Saul Bellow (“self-willed and unnatural”), Herbert Gold (“reminds me of nothing so much as a woman writer”), and J. D. Salinger (“the greatest mind ever to stay in prep school”). After initially praising the early writing of Philip Roth, the critic Irving Howe skewered the novelist in a 1972 essay in Commentary magazine, prompting Roth 20 years later to satirize Howe as the pompous critic Milton Appel in Roth’s 1983 novel The Anatomy Lesson. There is a lot to indicate that Jews mostly promoted the careers of non-Jews. The great postwar editor Jason Epstein’s authors—from Jane Jacobs, Peter Matthiessen, and Edmund Wilson to W. H. Auden, Vladimir Nabokov, and Paul Kennedy—were mostly non-Jews.

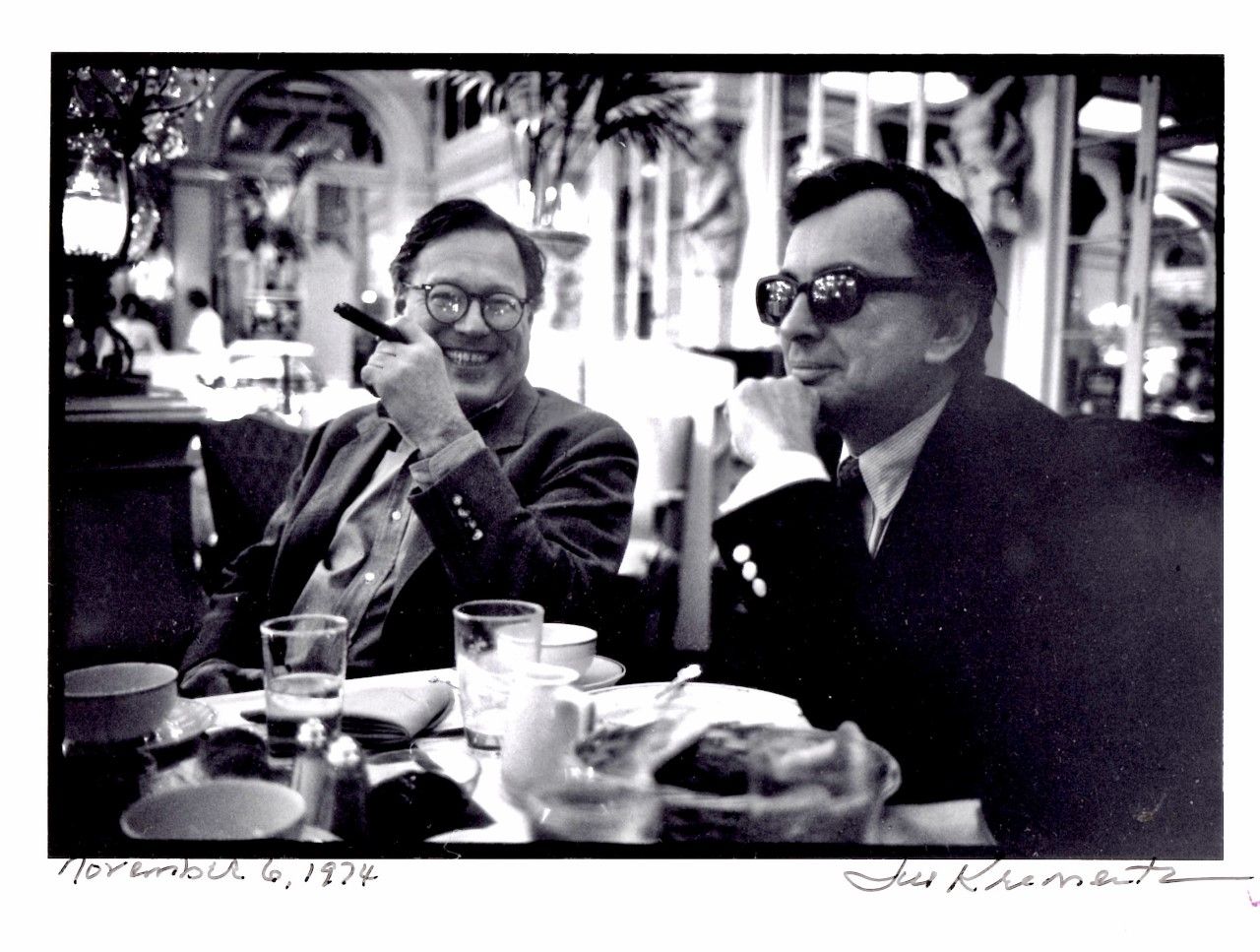

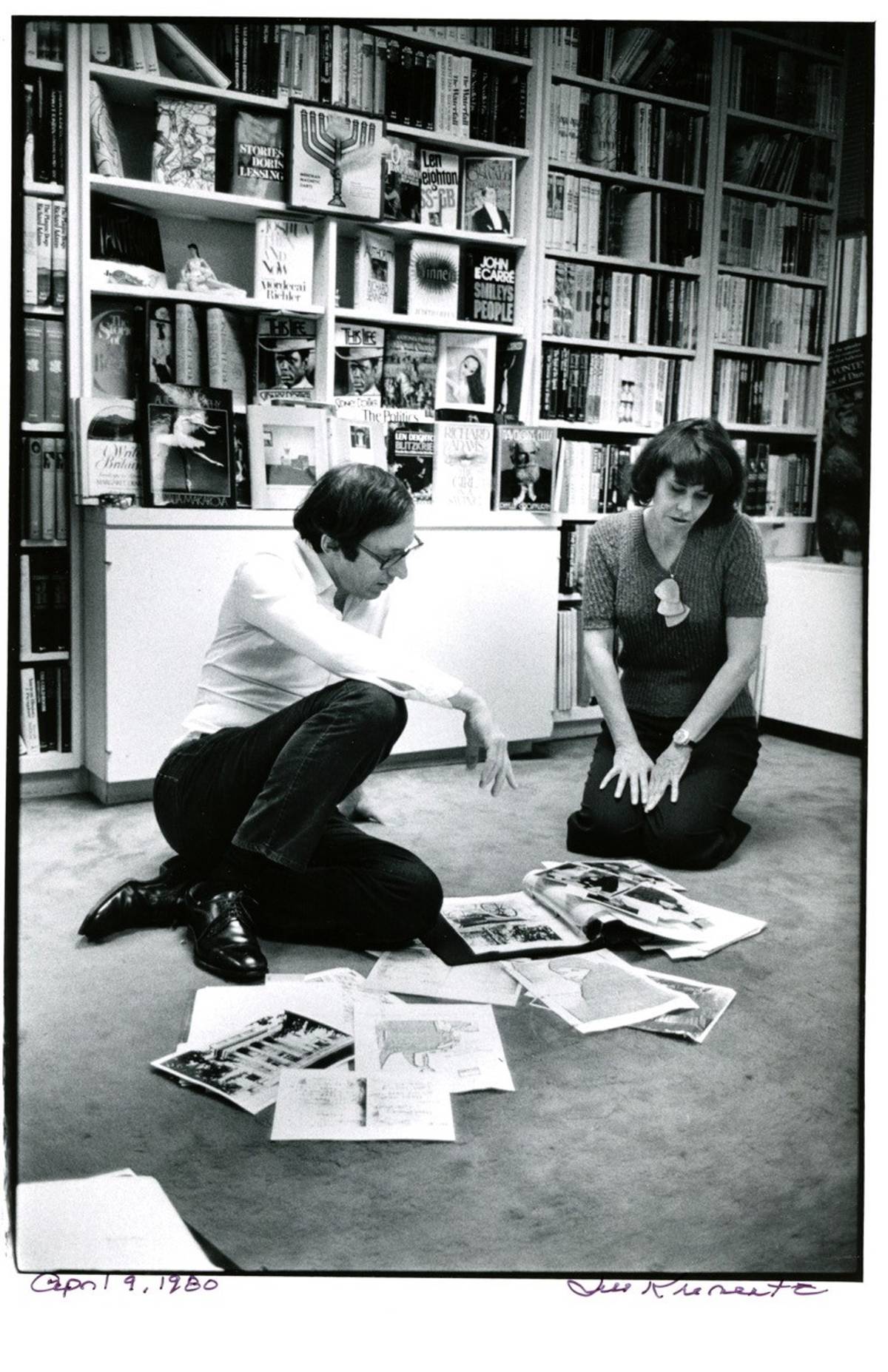

Bob Gottlieb and Barbara Goldsmith, 1980Jill Krementz

My own experience as an editorial assistant at The New York Review of Books for four years in the 1980s was that, to the extent that whether a contributor to the NYRB was Jewish was even a discernable issue, the journal’s two editors, Robert Silvers and Barbara Epstein, could be dismissive of writers they perceived as overly attached to their Jewish origins. While Isaiah Berlin was in at the Review, Kazin definitely was not. Barbara once explained to me that she disliked Kazin’s writing except when he was writing about the “ghetto.” She also liked to tell me how Edmund Wilson once had complained to her, “I wish Alfred did not like me so much.” Kazin, equally combative, once shared with me his feelings about Jason. “There is something about Jason Epstein,” he confided, “that just makes you want to punch him.” I recall a conversation with Bellow, who had been my undergraduate thesis advisor at the University of Chicago, in which he told me that he would not respond to an article in Commentary magazine disparaging his friend the poet John Berryman, which Silvers, my then-boss (mob boss?), wanted Bellow to write. “I don’t,” Bellow informed me when I asked him why he had declined to write a response to the Commentary piece, “believe in blowing up latrines.” The point here is that the famously feuding New York Jewish intellectuals of the postwar era were far more interested in fighting with each other than in literary log-rolling.

There is a lot of speculation, innuendo, and gossip in The Literary Mafia, along with something approaching slander in Lambert’s discussion of the careers of highly accomplished Jewish editors, publishers, and influencers, nearly all of them dead and unable to speak in their own defense. Piggy-backing on the controversial, anonymous 2017 Google doc that targeted purportedly misbehaving men in the media—because, hey, one has to go with the Zeitgeist—Lambert entitles one chapter “Women and Shitty Media Men.” Literary accomplishments, innovations, breakthroughs, artistic merit, and entire careers are ignored, held suspect, trivialized, criticized, or trashed. The playwright Lillian Hellman pops up only to endorse her friend Jason’s son’s book. Jason Epstein himself, often credited with inventing the serious paperback book (reprinting the out-of-print work of major European and American writers) and with modernizing the American book industry, is almost entirely discussed as a promoter of his son Jacob’s fleeting ambitions as a novelist.

The Literary Mafia’s handling of Jacob Epstein’s story is especially strained. In 1979 Jacob Epstein was exposed for having plagiarized some of the British novelist Martin Amis’ novel, The Rachel Papers, in his own first novel, Wild Oats. Epstein apologized, moved to Hollywood where he became a successful television producer and, properly, never published another work of fiction.

Lambert thinks it very telling that after the scandal The New York Review of Books never reviewed any of Amis’ books. Clearly, Lambert explains, this was a protracted NYRB hit job. But it should be obvious that the editors of the Review were in an impossible situation. If they published a negative review of a book by Amis, they could be accused of retaliation, while a positive notice of an Amis novel could be perceived as a disingenuous effort to make amends. There was no way the NYRB could review a novel by Martin Amis while Barbara Epstein, Jacob’s mother, was co-editor of the journal. And can anyone seriously contend that being ignored by the Review hurt Amis’ career?

The absence of any discussion of some of the important Jewish editors of the postwar period in Lambert’s screed is striking, to the point of seeming like a deliberate act of cultural erasure. Ted Solotaroff, among the most accomplished editors of his generation (founder of the journal New American Review, later titled American Review, which for years published innovative writing), is dispatched in a single, snarky sentence: “Ted Solotaroff’s career as a literary critic and editor at New American Review and Harper and Row was never separable from his friendship with Philip Roth, whom he saw as a kindred spirit beginning in their graduate-student days in Chicago, in part because they were from neighboring towns in New Jersey; Roth got Solotaroff the writing assignments that led to his first editorial job, so in a very concrete sense, Solotaroff owed his career to Roth.” The forced logic of this warped insinuation reduces an extended friendship to a life-altering favor reminiscent of those Balzac novels in which a single encounter catapults a character to social and professional prominence. Silvers, a central figure in American intellectual life for some 50 years, is referenced, en passant, only once, and Aaron Asher (the editor of Bellow, Roth, Carlos Fuentes, Charles Rosen, and Milan Kundera) not at all. Perhaps more astonishingly, William Shawn, longtime editor of The New Yorker, raised in a secular Midwestern Jewish home, is also entirely ignored, in a book that purports to be about Jewish literary influence in 20th century New York.

No doubt Shawn’s absence from Lambert’s book may be explained by the fact that his career undermines the whole thrust of The Literary Mafia. Under Shawn’s stewardship, The New Yorker was not especially associated with Jewish writing, but rather with showcasing literary goyim (John Cheever, E. B. White, John Updike, John Hersey, Donald Barthelme, Raymond Carver, Truman Capote, Dwight MacDonald). Salinger, although born to a Jewish family, could hardly be described as writer of Jewish themes. The most important work by a Jewish author that The New Yorker published—Hannah Arendt’s 1963 Eichmann in Jerusalem—was attacked as antisemitic by Jewish critics (though none of them could reply in a Letter to the Editor page because the magazine decorously—WASPily?—did not have one). There may be an interesting story in how Shawn, perhaps wanting to establish The New Yorker as a cosmopolitan (some would say middle-brow) magazine, mostly and timorously eschewed writers who came off as explicitly Jewish. But that would be the opposite of the story Lambert is determined to tell.

As affrontingly cynical and confused as Lambert’s thesis about inordinate Jewish influence is, he makes matters worse by seeking to tie his lurid fantasies of Jewish power to the (easily demonstrated) sexism of the postwar New York publishing world and to the (far less demonstrable) supposedly rampant nepotism. In linking misogynist behavior and nepotistic practice to his argument about Jews having so much undue sway over writers’ livelihoods Lambert inadvertently revives some ugly, well-burnished antisemitic canards about predatory male Jews, implying—without explicitly saying, of course—that sexism and nepotism are specifically Jewish problems. There is no question that, with some notable exceptions (the Jewish-born Blanche Knopf, Barbara Epstein, Diana Trilling, Midge Decter, the non-Jewish Nan Talese, Elisabeth Sifton, and Judith Jones), New York book and magazine publishing in the postwar period was a man’s world—as it was in nearly all other professions of the period.

Yet Lambert’s interest in bringing up misogyny in the context of a finger-wagging exposé of Jewish publishing cenacles suggests a kind of Me Too opportunism, in which now nearly every Jewish male editorial figure is retrospectively guilty because it was (thank you, Pierre Bourdieu) a system— and according to Lambert, a very corrupt one at that. Jews had assumed so much cultural capital, he implies that they could get away with anything. But the New York postwar publishing world was not monolithically hostile to feminist aspirations, and it published numerous talented female writers. While Lambert explores the editor Gordon Lish’s early advocacy of the writer Cynthia Ozick, he generally ignores evidence that Jewish male editors promoted the work of women. Ted Solotaroff, for example, oversaw the writing of dozens of female authors, including Kate Millett’s 1971 feminist classic Sexual Politics, excerpts of which first appeared in American Review. Is that typically what Jewish “shitty media men” do?

Lambert’s earnest, lengthy anti-nepotism case in his book is, as they say, found money. Who, after all, is really for nepotism (except, perhaps, Bellow’s son Adam, who, as Lambert is eager to point out, wrote a book defending it)? Lambert’s charge of Jewish nepotistic practice is based on a handful of cases, among them Alfred Knopf’s son Pat’s publishing fortunes; Jacob Epstein’s novel getting published; Adam becoming a publisher, and John Podhoretz succeeding his father, Norman, as editor of Commentary in 2007. (The “Postwar” of the book’s title runs heavily into overtime.) The wonderfully un-categorizeable novelist Steven Millhauser is included in this chapter not as the beneficiary of nepotism, exactly, but as someone in a position “of privileged literary access and inherited cultural capital.” Millhauser’s father was … a powerful literary agent? An influential publisher? A career-making editor? No, an English professor at the University of Bridgeport, Connecticut.

By way of proving the sexism of the New York Jewish literary establishment, Lambert focuses on what he characterizes as three “studiously neglected or misread postwar fictions” by three women—Ann Birstein’s 1973 Dickie’s List, Rona Jaffe’s 1958 The Best of Everything, and T. Gertler’s 1984 Elbowing the Seducer—what he calls “whisper novels,” romans à clef that exposed the unseemliness of all of that Jewish male publishing power (“studiously neglected,” needless to say, sounds like part of a conspiracy). Since Lambert’s book is interested in the alleged cultural control wielded by Jews and not in Jewish aesthetic achievements, Lambert doesn’t bother to make a case for the literary merit of these novels, which is understandable given that they are all interestingly topical, fetchingly silly, but decidedly forgettable minor works of fiction.

Yet novels only appear to interest Lambert if they can, as in Millhauser’s case, be interpreted autobiographically. Not content to indulge in tittle-tattle about, for example, who the real-life harasser referenced in Gertler’s tell-all novel might be, he hints at the need for some sort of public showdown. “Readers have no trouble treating books like Jaffe’s, Birstein’s, and Gertler’s as salacious and sometimes enjoyable gossip,” he writes with excited prosecutorial relish, “but have not seen them as grounds for action.”

The Literary Mafia keeps trying to drag the reader into a melodramatic fever dream in which Jewish male editors, agents, critics, and publishers promote Jewish writers and in which some of these same Jewish men discriminate against, decline to promote, ogle, harass, and abuse women while Jewish mothers and fathers strenuously use their power to advance the positions of their offspring. (Yale University Press really should have marketed Lambert’s book as part of a new literary genre, paranoid Jewish fiction.) In fact, The Literary Mafia is like a whole season of The Sopranos recast in a Manhattan, Jewish-dominated publishing world (call it The Shapiros) and conceived by a non-Jewish graduate of the Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop who, unable to get his first novel published, ends up, bitter and obsessed, working as a proofreader at, say, Publishers Weekly. (Hey, if not for that horrible New York Jewish clique, he could have been a literary contender!)

The unpleasant vibes given off by The Literary Mafia extend into the Acknowledgments pages at the end of the book, the last line of which finds the author thanking his two children thus: “I love you, and so I am doing my best not to do to you what some of the parents in this book did to their kids.” So add bad parenting to the bad rap the Jewish literary elite receives in The Literary Mafia. After 258 pages of a tendentious, gossip-driven diatribe masquerading as a work of serious, theoretically informed literary scholarship and as a brief on behalf of more enlightened publishing practices, a reader could be forgiven for wondering why Condé Nast publisher S.I. Newhouse, brooding over who to appoint as the editor in chief of Vogue in 1988, did not choose his co-religionist and New York City style icon, Cynthia Ozick. Postwar American culture really could have been so much better.