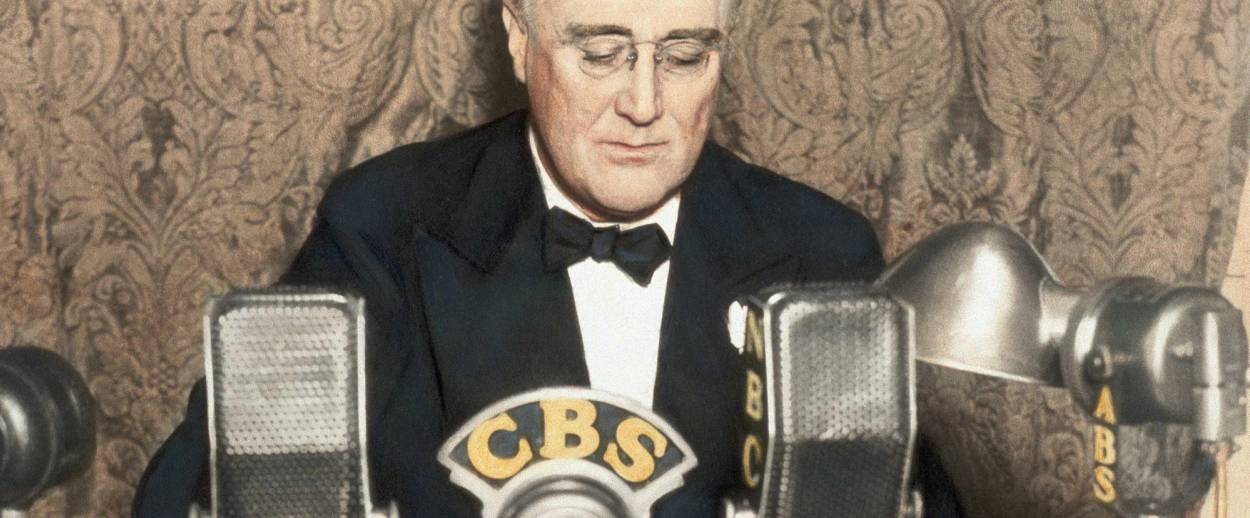

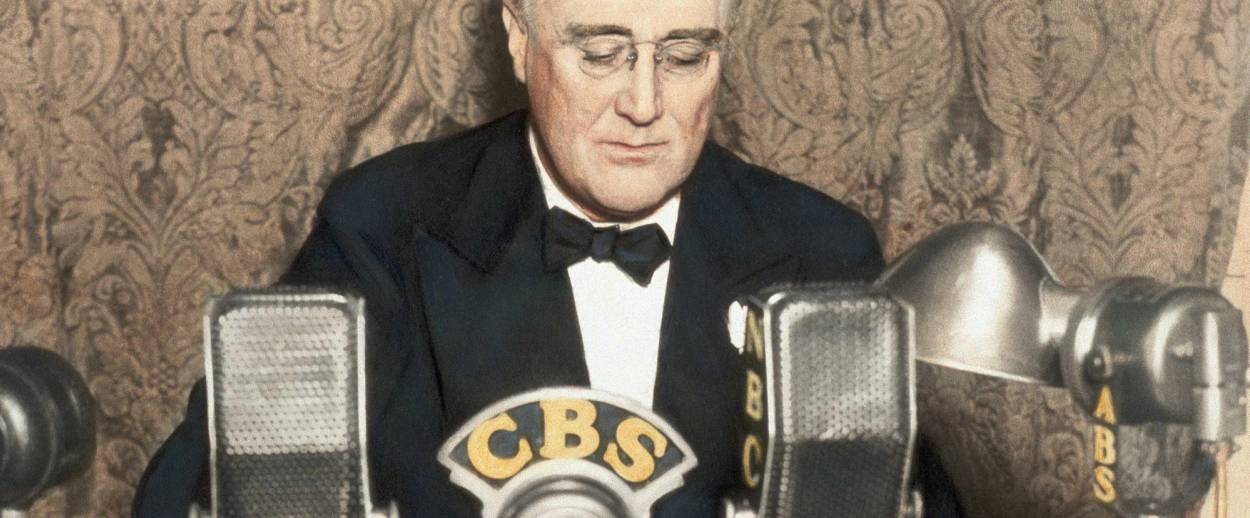

Franklin Roosevelt Betrayed Europe’s Jews

Leading American historians and rabbis covered for FDR’s mistake

On August 8, 1942, the American Consulate in Geneva received an urgent visit from Gerhart Riegner, the Swiss representative of the World Jewish Congress. A consular official noted that the young lawyer appeared in a state of “great agitation” as he conveyed the devastating information he had just obtained from a German industrialist with high-level contacts inside the Nazi bureaucracy. According to the industrialist (whose identity Riegner pledged to keep secret) the Hitler regime had launched a far-flung operation for the extermination of the Jewish people of Europe by means of poison gas in secret, industrial-style killing centers in the East.

Riegner asked that a cable summarizing these revelations be sent to the State Department and then forwarded to Rabbi Stephen H. Wise, president of the World Jewish Congress in New York. To the American diplomats it sounded “fantastical,” just another war atrocity rumor. Nevertheless, they agreed to transmit Riegner’s cable to their superiors in Washington. It was the first time that reliable information about Hitler’s Final Solution reached the U.S. government.

Gerhardt Riegner kept his promise to never reveal the name of his German informant. More than 40 years later, however, the historians Walter Laqueur and Richard Breitman were able to identify Riegner’s secret source as Eduard Schulte, the chief executive of a large mining company supplying strategic metals to the German war ministry. In Breaking the Silence: The German Who Exposed the Final Solution, the authors recounted the dramatic story of a “righteous gentile,” another Oskar Schindler, who risked his life to alert the world to the Holocaust. Part of Schulte’s information came indirectly from SS chief Heinrich Himmler, who had recently stopped at the Schulte mining works en route to a secret military installation near a small town formerly called Oswiecim, just across the old German-Polish border. As Laqueur and Breitman describe in their book, Schulte then learned that Himmler had observed the gassing of 450 Jews at bunker 2 of the Auschwitz death camp.

Schulte hoped the information that he passed on to Riegner would reach American government officials and the country’s Jewish leaders and prompt a forceful response by the United States and the Allies. He was convinced that “unless the Nazis are faced with some tangible major threat ... they will not be deterred,” according to Laqueur and Breitman. Unfortunately, Schulte had a somewhat exaggerated notion about the influence of the Jewish leaders. And he could not have imagined that the American president, the leader of the free world alliance against the Nazis, would be missing in action during this historically unprecedented moral challenge.

Nor could Gerhardt Riegner have known that the desperate warning he was trying to send to the American people would be suppressed for over three months by the U.S. State Department, which had been turned into a viper’s nest regarding the plight of the European Jews.

In the years before America entered the war, the Roosevelt administration ruled out political protest on behalf of Jews facing mounting persecution in Germany, because it wasn’t deemed to be in the “national interest”—that is, in the economic interests of a country still mired in the Great Depression. Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long, an admirer of Mussolini and a known anti-Semite, then became the administration’s point man in charge of refugee policy. Long erected a maze of bureaucratic barriers, (“paper walls,” as historian David Wyman later called them) which made it impossible to fill even the very restrictive immigration quotas established by Republican administrations in the 1920s. Hundreds of thousands of Jews fleeing the Nazis were effectively blocked from entering the United States.

In December 1940, the State Department disrupted an underground rescue network, led by the gallant journalist and Harvard literary editor Varian Fry, that helped over a thousand Jewish artists and scholars escape the Nazis through southern France. Intent on maintaining proper diplomatic relations with France’s collaborationist Vichy government, the department viewed Fry’s unauthorized operation as a political nuisance. It refused to renew Fry’s passport and then requested the Vichy police to arrest him in Marseille and force his return to the U.S.

After the U.S. entered the war, the Roosevelt administration convinced itself that efforts to aid Jews trapped in occupied Europe would divert resources from the military campaign against the Axis powers. Thus when the Riegner cable arrived at the State Department on Aug. 10, 1942, it was treated not merely with appropriate skepticism, but also downright obstructionism. Fearing that news of the extermination would encourage unwanted public pressure to do something about the endangered European Jews, the State Department declined to pass Riegner’s report on to Rabbi Wise. A top diplomatic official warned that Wise “might kick up a fuss” if he found out the department was withholding information about the fate of the Jews. The State Department then asked the Geneva consulate to refrain from transmitting any more reports from Riegner unless they could be shown to be in the “national interest.”

Riegner, though, had the foresight to present Schulte’s information to the British Consulate in Geneva with a request that it be sent to London and then on to Rabbi Wise. Thus Wise received the Riegner cable not from representatives of his own government, but from a British official. Shocked and distraught, yet knowing Riegner to be reliable, Wise immediately placed a telephone call to Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles to report what he believed to be vital new information about the Jewish catastrophe in Europe. He also pressed for a direct meeting with President Roosevelt.

Welles didn’t let on that the State Department had been sitting on the Riegner cable for almost three weeks. Nor did Rabbi Wise get a meeting with the president. Instead, Welles asked the rabbi to maintain secrecy while the department supposedly checked the cable’s veracity. Wise agreed to keep the matter under wraps and refrained from stirring up public protest.

During the next three months of U.S. government-enforced silence, trains packed with Jews continued to roll into Auschwitz, Treblinka, Sobibor and other killing centers in the East. It’s true that the FDR administration was still unaware of the secret Wansee Conference of Jan. 20, 1942, in which top Nazi officials meticulously planned the logistics of the Final Solution. However, at a rally in Berlin 10 days after Wansee Hitler boldly announced that “the result of this war will be the complete annihilation of the Jews.” The Fuehrer’s speech was monitored in Washington and London. Any reasonably interested American administration should have been able to connect the dots—taken together, Hitler’s “annihilation” speech followed months later by the revelations from the “German industrialist” would confirm the truth about the ongoing, systematic massacre of the European Jews.

As more information about the death camps arrived in Washington from other sources, the State Department found it increasingly difficult to maintain the news embargo. Finally, on Nov. 24, more than three months after Riegner’s original telegram had arrived in D.C,. Undersecretary Welles informed Rabbi Wise that the cable had been verified and could now be made public. That evening Wise held a press conference in Washington, D.C., to announce the U.S. government had confirmed that Hitler “ordered the annihilation of all Jews in Europe” and 2 million had already been murdered.

Five reporters attended Rabbi Wise’s presser, none from TheNew York Times or Washington Post. The country’s two leading newspapers ran a few paragraphs from the wire services, burying Wise’s announcement deep inside the next day’s papers. Time and Newsweek ignored the news entirely. It didn’t help Wise’s credibility with the press that the State Department declined to comment on his statement. Still, the fact remains that the “mainstream media” (as we now call it) was offered a scoop on the greatest mass murder story in history and merely shrugged.

It has been said (usually by journalists themselves) that “journalism is the first rough draft of history.” In the case of America’s response to the Holocaust the historians didn’t do much, at least at first, to improve the drafts written by the reporters at the scene.

Within two decades after the war’s end, major biographies of FDR were published, including by reputable scholars such as James MacGregor Burns, Frank Freidel, and Eric Goldman. These studies made important contributions to American political history—except in one crucial area. Almost across the board the biographers uncritically echoed the Roosevelt administration’s self-exculpatory account of America’s failure to come to the aid of the European Jews. According to the consensus view first promulgated by members of the government and later echoed by journalists and historians, the U.S. could do nothing to save Jews under Hitler’s control because such endeavors would have diverted resources from the first and ultimate priority of winning the war. Defeating Nazi Germany on the battlefield was the only possible way to rescue any substantial number of Jews.

James MacGregor Burns’ two-volume biography of FDR, published starting in 1956 and concluded in 1970, was widely regarded at the time as the best of the genre. It received the Pulitzer Prize in history and the National Book Award. Yet in over 1,100 total pages Burns barely mentions Breckinridge Long and says nothing about the Riegner cable. Nevertheless, the historian confidently asserts that the logistical and military problems of trying to rescue Jews in occupied Europe were too “intractable.” As with Roosevelt’s other preeminent biographers, Burns simply elides the possibility that the president might bear any personal moral responsibility for America’s indifference to the Holocaust.

Thankfully, historiography is a self-correcting process. By the late 1960s, a new group of scholars stepped into the vacuum, uncovering new archives and challenging the establishment Roosevelt historians. Works such as Arthur Morse’s While Six Million Died and Henry Feingold’s The Politics of Rescue offered convincing evidence that the Roosevelt administration obstructed practical proposals for saving Jews facing extermination, just as it had previously blocked asylum for hundreds of thousands of Jews fleeing Nazi persecution.

Finally, David Wyman’s massive 1984 study, The Abandonment of The Jews: America and The Holocaust, 1941-1945, demolished virtually every argument used by the Roosevelt biographers to exonerate the president. It also became a surprise bestseller. Wyman’s most disturbing revelation (originally published in Commentary magazine) was that in the summer of 1944 U.S. warplanes were flying over Auschwitz on their way to attacking German oil refineries farther north. The bombers could have dropped some of their payloads on the death factories then operating on overtime, or on the rail lines leading to the camp—a proposal advocated by a wide array of Jewish leaders in the United States and Palestine. But the anguished pleas for action were rejected out of hand by the administration. According to an official War Department memo, a military mission against Auschwitz would have resulted in diverting resources “essential to the success of our forces now engaged in decisive operations elsewhere.”

Wyman demonstrated that the government’s rationale was riddled with deception and hypocrisy. At the same time that the administration ruled out bombing Auschwitz, the U.S. military command pulled more than 100 heavy bombers out of regular strategic missions to drop supplies to units of the Polish Home Army which had risen up against the Nazis in Warsaw. The operation had no appreciable effect on the doomed Polish revolt and most of the material fell into enemy hands. Nevertheless, a War Department report stated that “despite the tangible costs which far outweighed the tangible results achieved, it is concluded that this mission was amply justified. America kept faith with its ally.” Clearly, the Jewish people were not viewed by the U.S. government as an ally that it had to “keep faith” with.

“Franklin Roosevelt’s indifference to so momentous an historical event as the systematic annihilation of European Jewry emerges as the worst failure of his presidency,” Wyman concluded.

In 1984 I wrote an extended essay based on Wyman’s book for the Village Voice, where I was then a regulator contributor. I was somewhat amazed that the editors of this bastion of New York liberalism decided to place the article on the cover, under a banner headline: “Bystander to Genocide: Roosevelt and the Jews.” I took it as a sign that even progressives were willing to take a critical look at FDR’s legacy as America’s greatest “humanitarian” president.

Wyman’s book represents one of those rare occasions when a single work of scholarship overturns the previous historiographical consensus. An example of how Wyman influenced future historians to reconsider the Roosevelt administration’s record on the European Jews is Michael Beschloss’ 2002 book, The Conquerers: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Nazi Germany, 1941-1945. Beschloss was a student of James MacGregor Burns and is now often referred to as “the nation’s leading presidential historian.” Thus his conclusion about Auschwitz is significant: “With more than a half-century of hindsight, it is clearer now than in 1944 that the sound of bombs exploding at Auschwitz would have constituted a moral statement for all time that the British and Americans understood the historical gravity of the Holocaust.”

Beschloss goes even further than Wyman and lays the blame squarely at President Roosevelt’s feet for the administration’s decision to spare the Auschwitz death factory, of all places, from U.S. bombing raids. Citing a newly discovered letter from Secretary of War John McCloy, Beschloss quotes this comment made by Roosevelt about the proposal to attack Auschwitz: “If it’s successful it’ll be more provocative and I won’t have anything to do [with it] … We’ll be accused of participating in this horrible business.”

In a moving e-book on Varian Fry’s heroic rescue mission, the novelist Dara Horn allows herself to meditate on how it happened that only a few rare individuals became rescuers, while most people—and nations—remained bystanders to the extermination. “Why didn’t everyone become Denmark?” Horn asks.

Even David Wyman wasn’t able to answer that haunting question. Perhaps only a psychologist could. Or maybe it takes a novelist like Horn to convincingly imagine the moral debacle of the Roosevelt administration’s silence in response to the Riegner cable, or explain how a revered leader of American Jewry was lured into cooperating with the government to suppress news of the extermination for more than three months.

Rafael Medoff is neither a psychologist nor a novelist. He’s a Holocaust historian, yet he has come closer than anyone before him to explaining the inexplicable. He does so in a new book titled, The Jews Should Keep Quiet: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, and the Holocaust.

Medoff sets himself the task of answering two pivotal questions: “How did President Roosevelt manage to prevent the American Jewish leadership, with its longstanding tradition of seeking U.S. government intervention on behalf of persecuted Jews abroad, from acting similarly during the Nazi era? How did FDR keep Rabbi Wise and other leading Jews quiet, so that his policy regarding European Jews could proceed unhindered?”

Using new materials from the Wise archives, Medoff closely examines the psychologically fraught relationship between the putative leader of the small American Jewish community and a very powerful and popular American president. He begins by quoting from an amazing letter by Rabbi Wise to his son on Feb. 16, 1943: “Justine and Shad [Wise’s daughter and son-in-law] had dinner with the Roosevelts on Saturday, including the president,” Wise wrote. “Justine said [President Roosevelt] sent his affectionate regards to me.” Wise then added this sad but revealing sentence: “If only he would do something for my people.”

The letter was written three months after Rabbi Wise was pressed into cooperating with the Roosevelt administration to maintain silence about the extermination of the European Jews (“my people.”) He ended up in this moral trap, according to Medoff, because of his coveted personal access to President Roosevelt, which then served to burnish his credentials as a major leader of American Jewry. To preserve his privileged status at the White House Wise found it necessary to contain the growing outrage from American Jews over the president’s apparent indifference to the fate of their European brethren.

Of course, there were no leadership elections in the often fractious American Jewish community and individual Jews never chose Wise to be their leader, any more than they elected their local rabbis. But Wise had a very impressive and broad set of qualifications for the role: He was simultaneously president of the World Jewish Congress and the American Jewish Congress; founder and chief rabbi of the Free Synagogue in Manhattan; founder and head of the Jewish Institute of Religion; one of the founders and a board member of the ACLU; a board member of the NAACP. He was a proud American Zionist, passionately concerned with the fate of his fellow Jews around the world, but also a pillar of American progressivism and liberalism—a combination one now needs to remind people– that was for many decades unexceptional before it became unspeakable.

Politically, Wise started out far to the left of FDR, supporting Socialist party candidate Norman Thomas in the 1932 presidential election. He then enthusiastically enlisted as a soldier in Roosevelt’s New Deal. After Hitler’s rise to power Wise spoke out forcefully about the dire situation of Jews in Nazi Germany. To his credit, he also urged the Roosevelt administration to loosen the rigid immigration quotas so that more European Jews could find asylum in the United States.

But Rabbi Wise soon found himself navigating a delicate political balancing act. As his prominence grew within the president’s circle of Jewish advisers, an inevitable tension surfaced between his loyalty to the New Deal cause and to FDR personally (whom he affectionately called “boss”) and his own role as a defender of Jewish interests.

That tension first surfaced during the clamor among American Jews (and quite a few non-Jews) to protest the Nazi persecution of European Jewry by launching a boycott of German goods. Wise initially opposed the boycott as too risky, then came around to supporting it. At the same time, he made sure to let the White House know he was doing his best to temper the growing militancy on the boycott issue within the Jewish community.

To make his own political task easier Wise urged the president to at least verbally condemn the Hitler regime for its anti-Jewish policies. But FDR steadfastly refused to speak out about what he considered Germany’s “internal affairs.” Instead, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, representing the views of the administration, declared that a boycott would damage U.S. “economic interests.” The implication was that Jewish Americans protesting against Hitler were harming America.

The same contradiction between Wise as an American Jewish leader voicing his community’s concern over the Nazi onslaught and Wise as a domestic ally of President Roosevelt would surface over and over again throughout the 1930s. After each new outrage in Germany, from the Nazi Olympics, to the Nuremberg rallies, to Kristallnacht, Roosevelt steadfastly refused to condemn Hitler. And each time Rabbi Wise felt called upon to mollify American Jews while avoiding personal criticism of the president.

Wise sincerely believed that maintaining access to the White House would allow him to accomplish good things for his fellow Jews in America and Europe. For all the modern trappings of his politics, Wise followed centuries of European Jewish leaders who believed the key to defending Jewish interests lay in maintaining good relations with the local sovereign, which sometimes required turning a blind eye to Jewish persecution to preserve their influence with the court. In American politics, the strategy of gaining access to powerful elected officials often does work out well for the leaders of small minority groups and for the constituencies they represent. In this case, however, Wise was overmatched by a president who was a master at the game of personal politics.

“Franklin Roosevelt took advantage of Wise’s adoration of his policies and leadership to manipulate Wise through flattery and intermittent access to the White House,” Medoff writes. “Calling Wise by his first name made the rabbi feel he was a personal friend of the most powerful man on earth.”

It’s bad enough to cling to a strategy of political access when it is clearly failing. Even less forgivable is the manner in which Wise sought to undermine independent Jewish groups and individuals who favored a politics of public protest. Wise was a great believer in democracy, but not so tolerant of democratic dissent within the Jewish community. He assumed that because of his personal relationship with the president, he had become the indispensable leader of American Jewry and therefore was due a great deal of deference from Jewish activists.

In 1934 two of those activists, the famous lawyer Samuel Leibowitz (defense counsel for the Scottsboro Boys) and Leo Gross, editor of the Brooklyn Jewish Herald, launched a new grassroots organization called Brooklyn Jewish Democracy. The group announced that it stood for “militant leadership for the Jewish people” in combating anti-Semitism in the U.S. and abroad. When 4,500 people showed up for the group’s first major event, Rabbi Wise decided this was a threat to his own leadership. From the pulpit of the Free Synagogue he denounced the leaders of the organization as “our foremost enemies” and lobbied with elected officials to curb their influence.

The greatest challenge to Wise’s leadership and to his strategy of courting President Roosevelt behind closed doors came from a Zionist organization initially called the Committee for a Jewish Army of Stateless and Palestinian Jews. The group’s leader was Peter Bergson, a 30-year-old Palestinian Jew stuck in the U.S. for the duration of the war. (Bergson was his nom de guerre. His real name was Hillel Kook and he was a nephew of the leading rabbinical figure in Palestine, the sainted Rabbi Abraham Kook.)

Kook had been a young officer in Jerusalem of the militant Zionist underground group, Irgun Tzvai Leumi. In 1940 he was sent on a mission to the United States to work with the titular commander of the Irgun, Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, on a campaign to create a separate Jewish army that would participate in the free world alliance against the Nazis. Since the Jewish people were Hitler’s No. 1 target, Jabotinsky argued, they should be recognized as an ally in the military struggle against Nazi Germany. (Jabotinsky’s insight became tragically prophetic a few years later when the U.S. government refused to bomb Auschwitz because the Jews, unlike the Poles, were not considered “allies.”)

Jabotinsky died in 1940 and Kook, now Bergson, took over as leader of the Jewish army committee. After Rabbi Wise’s press conference about the Riegner cable, Bergson and his colleagues suspended Zionist activities and devoted all their political energies toward rousing public opinion about the extermination of the European Jews.

The “Bergson group,” as they came to be known, proved that Rabbi Wise was wrong when he insisted that the only way for American Jews to aid the endangered Jews of Europe was to shun public protests and support his quiet diplomacy behind the closed doors of the White House. The group quickly organized a public meeting in New York City called the Emergency Conference to Save the Jewish People of Europe, where panels of experts in the fields of diplomacy, psychological warfare, and rescue logistics made recommendations for specific U.S. rescue initiatives in Europe.

The group then reorganized itself as the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe and launched a full-scale public campaign to create a separate government agency devoted solely to rescuing European Jews. One of the committee stalwarts was Ben Hecht, the famous journalist, playwright, and Hollywood screenwriter. The immensely talented Hecht wrote provocative full-page ads that ran in The New York Times (each one of which infuriated Rabbi Wise) castigating the Roosevelt administration for its inaction on the extermination. Hecht was also the main inspiration and chief scriptwriter for a massive musical pageant about the doomed European Jews titled, “We Will Never Die.” The production was performed in New York’s Madison Square Garden on March 9, 1943. Twenty thousand people filled the garden for each of two performances and thousands more listened on microphones on the streets outside.

Rabbi Wise didn’t take kindly to what he viewed as a rival group brashly speaking out against his friend, President Roosevelt, and capturing public attention. He became even more outraged after the Bergson group helped organize a march by 500 Orthodox rabbis from the Capitol to the White House to protest the lack of action about the extermination.

Shortly after the march of the rabbis, Wise and Peter Bergson had their only face-to-face meeting. Wise, the 68-year-old American Jewish statesman, accused Bergson, the 30-year-old Palestinian Jew and Irgunist, of “endangering American Jewry” with his publicity tricks. “Who appointed you?” Wise demanded. Bergson answered that no one appointed him, which was why he was free to act according to his conscience.

Describing that encounter, Medoff concludes, “it was precisely such independence of thought and action that ultimately enabled Bergson to have a direct impact on the American government’s response to the Holocaust.”

The outsider from Palestine demonstrated a more acute understanding of the possibilities of American politics in cases of emergency than the seasoned Rabbi Wise. Recognizing that the president could not be moved on the rescue issue, the Bergson group went around the White House and appealed directly to the American people and their elected representatives in Congress. Bergson had a knack for attracting support across ideological and party lines. Prominent American politicians from both sides of the aisle joined the committee’s campaign for the creation of an official U.S. rescue agency, including pro-New Deal Sen. Will Rogers Jr., Republican Sen. Guy Gillette, and New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia.

By the end of 1943, the Bergson group was close to achieving its major objective. Congressional hearings were scheduled for a resolution, introduced by Sens. Rogers and Gillette, calling on the administration to establish the rescue agency. The cause then received a big boost from several “whistleblowers” within the Roosevelt administration.

Treasury Department officials Josiah DuBois and Randolph Paul had been tracking Undersecretary of State Breckinridge Long’s sabotage of every effort to provide asylum in the United States for the endangered European Jews. The young officials discovered that Long had falsified documents about the extermination and then lied blatantly in public testimony about the total number of visas the department had granted to European Jews.

DuBois compiled an 18-page dossier titled, “Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of This Government in the Murder of the Jews” and delivered it to his boss, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. The report stated that State Department officials (primarily Long) “not only failed to use the Government machinery at their disposal to rescue Jews from Hitler, but have even gone so far as to use this Government machinery to prevent the rescue of these Jews.”

Secretary Morgenthau presented the report to President Roosevelt. In a face-to-face meeting, Morgenthau essentially confronted the president with a stark choice: Either establish a rescue agency yourself or deal with a major scandal, plus endure political humiliation when Congress passes its own rescue resolution.

On Jan. 22, 1944, two days before the full Senate was scheduled to vote on the Rogers-Gillette rescue resolution, the president created the new agency by executive order and called it the War Refugee Board. The Roosevelt biographers later gave the president credit for creating the rescue agency, but the truth is that he had to be dragged kicking and screaming to finally do something decent for the Jewish victims of the Nazis.

At the late hour of its creation, the WRB was able to accomplish far too little. Still, by some estimates, the rescue agency was instrumental in saving as many as 200,000 Jews who otherwise would have been sent to the death camps. The WRB’s biggest achievement came in Hungary where the heroic Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg served as one of its secret emissaries. Using his diplomatic credentials and creating safe houses to thwart Nazi roundups and deportations, Wallenberg was responsible for saving thousands of Jews in Budapest alone. Even as the Roosevelt administration refused to bomb Auschwitz, Wallenberg was literally pulling Jews off railway cars bound for the Auschwitz death camp.

We don’t know how many more Jews might have survived if a U.S. government rescue agency had been created, as it should have been, soon after the Riegner cable arrived at the State Department with its deadly accurate report about the Final Solution. What we do know for sure is that every one of the Jews rescued by the WRB and the hundreds of thousands of their descendants became living testimony to the absurdity of the Roosevelt administration’s mantra that nothing could be done for the Jews until the war was won.

Dozens of world leaders gathered in Jerusalem last week to mark the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. As in past ceremonies, eloquent statements were issued about the human catastrophe of the Holocaust and the need to combat any renewal of anti-Semitism.

It would be useful and somewhat more educational if more time was spent focusing on the choices made by people and governments along the path that led to Auschwitz. The world needs to be reminded that there were not only the perpetrators of the Holocaust, but also the bystanders who refused to take any risks to intervene. Dara Horn’s haunting question should be asked over and over again: “Why didn’t everyone become Denmark?”

Any commemoration of the Holocaust must note that a few exceptional human beings did “become Denmark.” There were the rescuers, like Varian Fry, Eduard Schulte, and Raoul Wallenberg, who risked their lives. (In Wallenberg’s case he lost his life when he disappeared into a Soviet gulag after the Red Army conquered Budapest.) And there were the advocates for rescue such as Peter Bergson, Ben Hecht, and the Treasury Department whistleblowers, who courageously spoke and acted. They should be honored, not least because they salvaged a little bit of the free world’s honor.

Finally, we should consider this essential lesson of the Holocaust for America: There can be no American greatness if there is no American moral leadership, a leadership that commands the United States to sometimes take risks, even at the expense of narrow definitions of the “national interest.” As we memorialize Auschwitz, we should honor the imperative in the question, “why didn’t everyone become Denmark?” and ask of ourselves—if not America, who?

Sol Stern is a former fellow of the Manhattan Institute and has written for many publications, including City Journal, Commentary, The Daily Beast and the Wall Street Journal.