It’s a hallowed Parisian tradition that, come autumn, as the kids go back to school and the conkers begin to fall, the publishing houses start claiming every new release as a candidate for the most prestigious literary prizes. From early September through the end of October furious debates take place on the opinion pages of Le Monde, Libération, and the satirical weekly Le Canard Enchaîné. Prominent intellectuals who love an excuse to get their name in the papers, publishing directors pushing their own novels and other novelists with books up for the same awards use the debate over the upcoming prizes as an excuse to put forward their agendas, and all this amounts to a very effective—and inexpensive—marketing campaign.

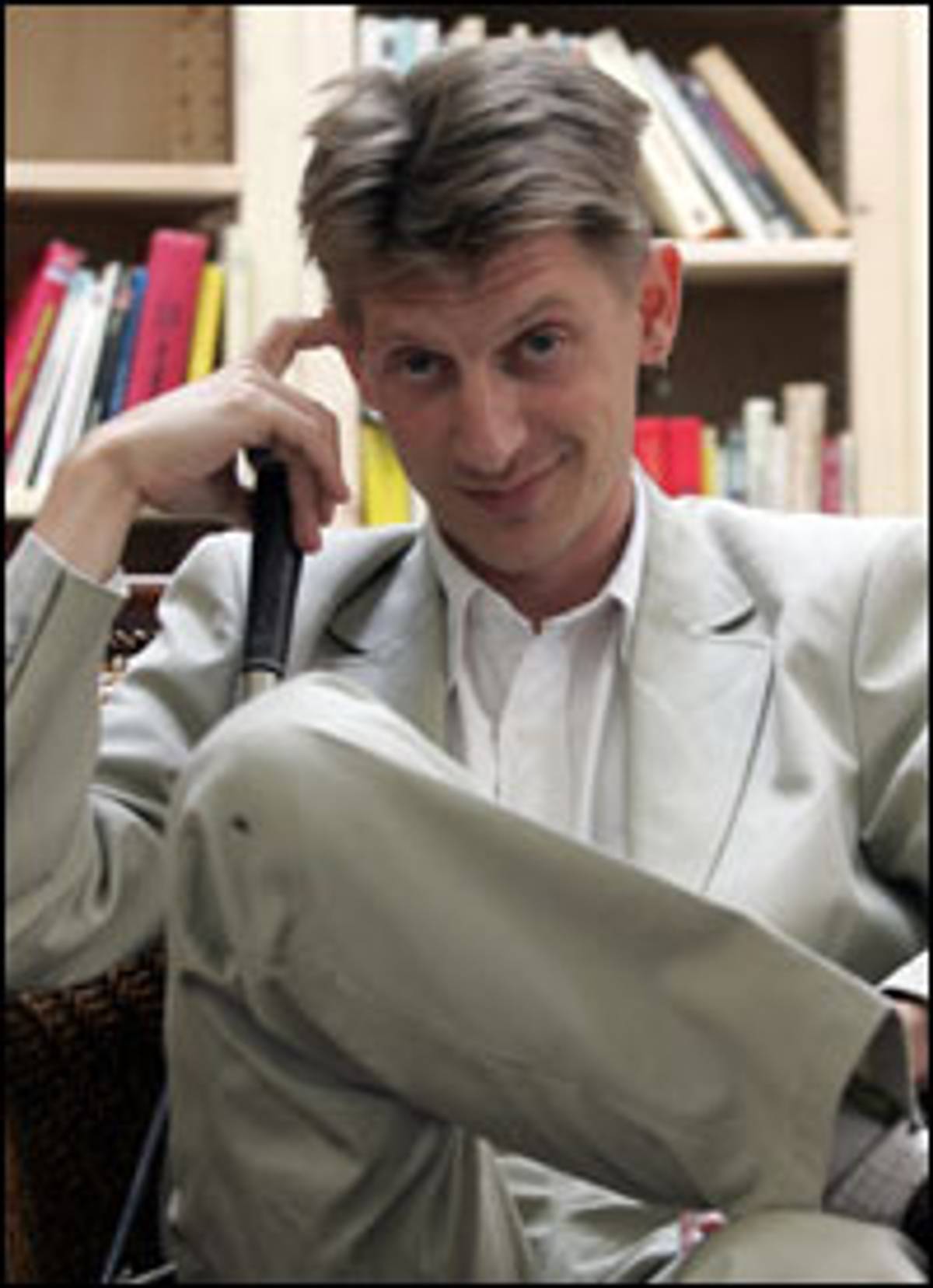

Even by the standards of literary Paris, the awarding of both the Grand Prix de l’Académie Française and the Prix Goncourt to the American Jonathan Littell for his novel Les Bienveillantes has caused—if not quite a scandal—a definite stir. On the one hand people in France are flattered (if a little perplexed) that a writer who could have written in English actually chose to do so in French. For a country that seems permanently on the edge of a nervous breakdown about the dwindling global importance of its language there could surely be no greater compliment. On the other there is palpable outrage that an American has not only dared to write a novel about the Holocaust—the consummate European experience—but has been awarded two of the most prestigious French literary prizes for his trouble. One of the Goncourt jurors was so opposed to the award going to Littell that he voted for Elie Wiesel —who wasn’t even on the shortlist.

Littell certainly raised the stakes in giving a voice to the fictional Maximilian Aue, a coolly unrepentant former SS officer who has decided to tell his story. Over the course of 900 pages Littell pulls no punches; his often horrifically graphic descriptions of brutality led Michael Mönniger, Paris correspondent for Die Zeit, to charge Littell with indulging in a pornography of violence.

Claude Lanzmann, who has said that he considers himself and Raul Hilberg the only people who understand how to represent the Holocaust, described Littell’s novel as nothing less than “a poisonous flower of evil” in Le Journal de Dimanche. “In spite of the best efforts of the author,” he goes on to say, “these 900 stormy pages are completely unconvincing…. The book as a whole is simply a scene setter and Littell’s fascination for the villain, for horror, for the extremes of sexual perversion, work entirely against his story and his character, inspiring discomfort and repulsion, even though it’s hard to say against who or what….” Le Nouvel Observateur considered Lanzmann’s remarks “moderate.” God save anyone who gets a bad review from him.

For some, the mere fact of giving voice to the killer rather than to his victims is pushing the boundaries of moral acceptability. German historian Peter Schöttler, writing in Le Monde, claimed that by forcing the reader into an empathy with the SS the novel is more Hollywood than literature or history—a claim strongly refuted a fortnight later on the same pages by fellow specialist in German history Jean Solchany’s assertion that Lanzmann’s and Schöttler’s “narrowness of vision” borders on “philistinism.”

Feminist novelist Christine Angot (no stranger to controversy herself, she remains best-known for her autobiographical novel Incest) wrote a lengthy article in the magazine Têtu trashing Littell, basing her argument on the claim that a Jew couldn’t possibly get under the skin of an SS officer. This failure of imagination on her part may stem from her allegiance to a French strand of feminist critical theory that insists on the indivisibility of the self and the text, or may just be pure spite, given that her novel Rendez-vous—a confessional “text” about Angot’s real-life affair with a Parisian banker—didn’t make this year’s Goncourt shortlist.

But this is France, where emotions run high with regard to all things literary. Within six hours of the announcement that Littell had won the Goncourt, more than 150 lengthy and passionate comments had been posted on the popular literary blog of Pierre Assouline, a venerable literary journalist and writer who adored Les Bienveillantes.

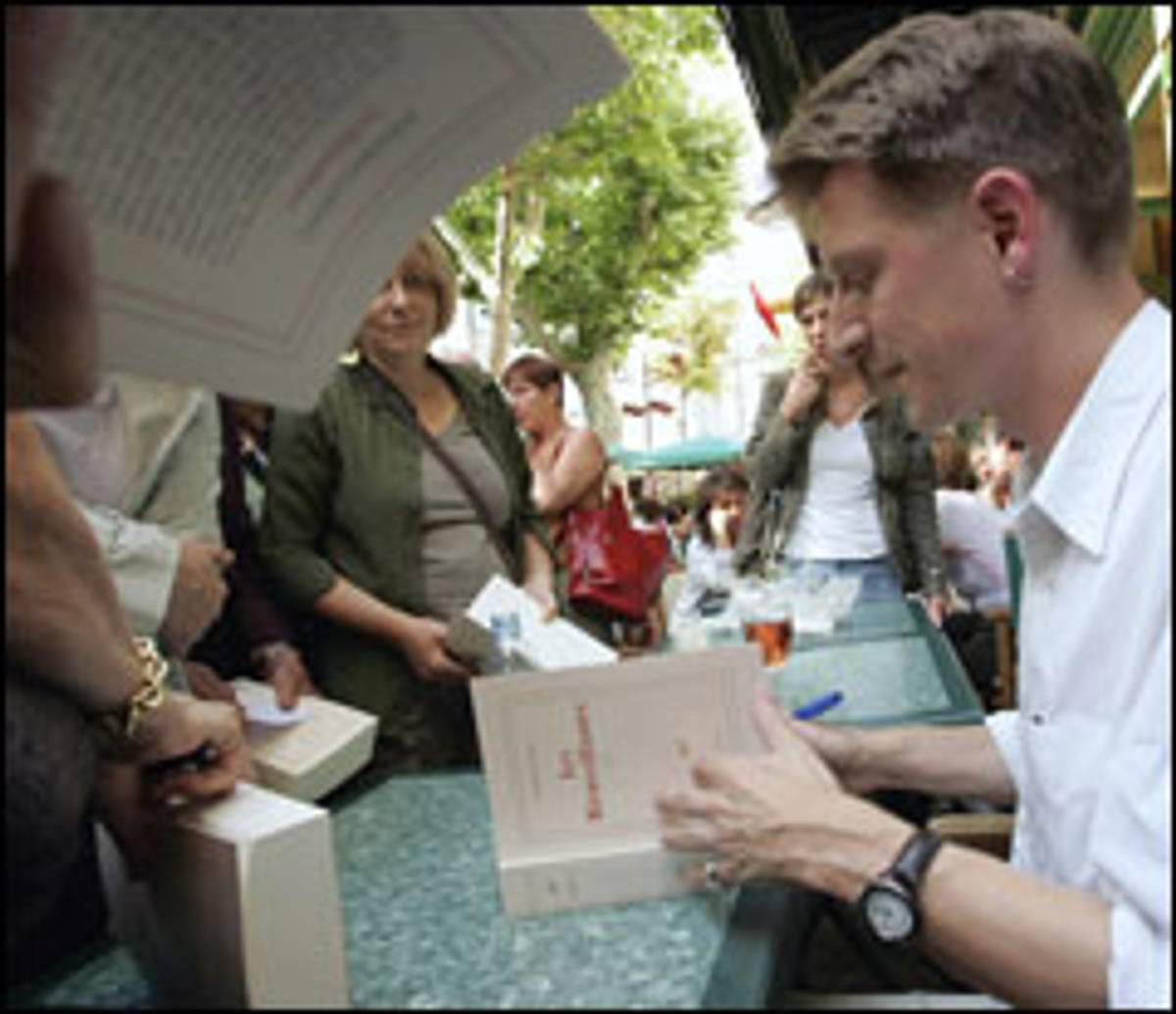

The critiques by Lanzmann, Angot and the rest don’t seem to have made a dent in sales of Les Bienveillantes which this week topped 250,000 (it’s also the bestselling book on Amazon.fr). Paper set aside to print the latest Harry Potter has been requisitioned by Gallimard, Littell’s publisher, to deal with the unexpected demand. Meanwhile Littell—who spent years doing field work in Africa and Eastern Europe for the aid agency Action Contre la Faim—has distanced himself from the whole award merry-go-round, deputizing his publisher to accept both prizes on his behalf. Since the book’s publication he has given only a few interviews from his home in Barcelona. This has, of course, only added to his mystique.

As Le Figaro pointed out on Tuesday—the day after the Goncourt was awarded—it tells you something about France that “six months before a Presidential election, all the front pages this morning are devoted to literature.” Whether this is because in the end the Goncourt shortlist offered a choice that was less depressing than the current featherweight tussle between the various Socialist candidates, or the grandstanding of the Kärcher-wielding Sarkozy, is open to debate, preferably, like the Goncourt, in the private dining room of one of Paris’s oldest and finest restaurants, Drouant, where the jury makes its decision over lunch in a tradition that dates from 1914. When it comes to the finer things in life it seems that the French still have something to teach the rest of us.