The Ghost Landmarks of the East End

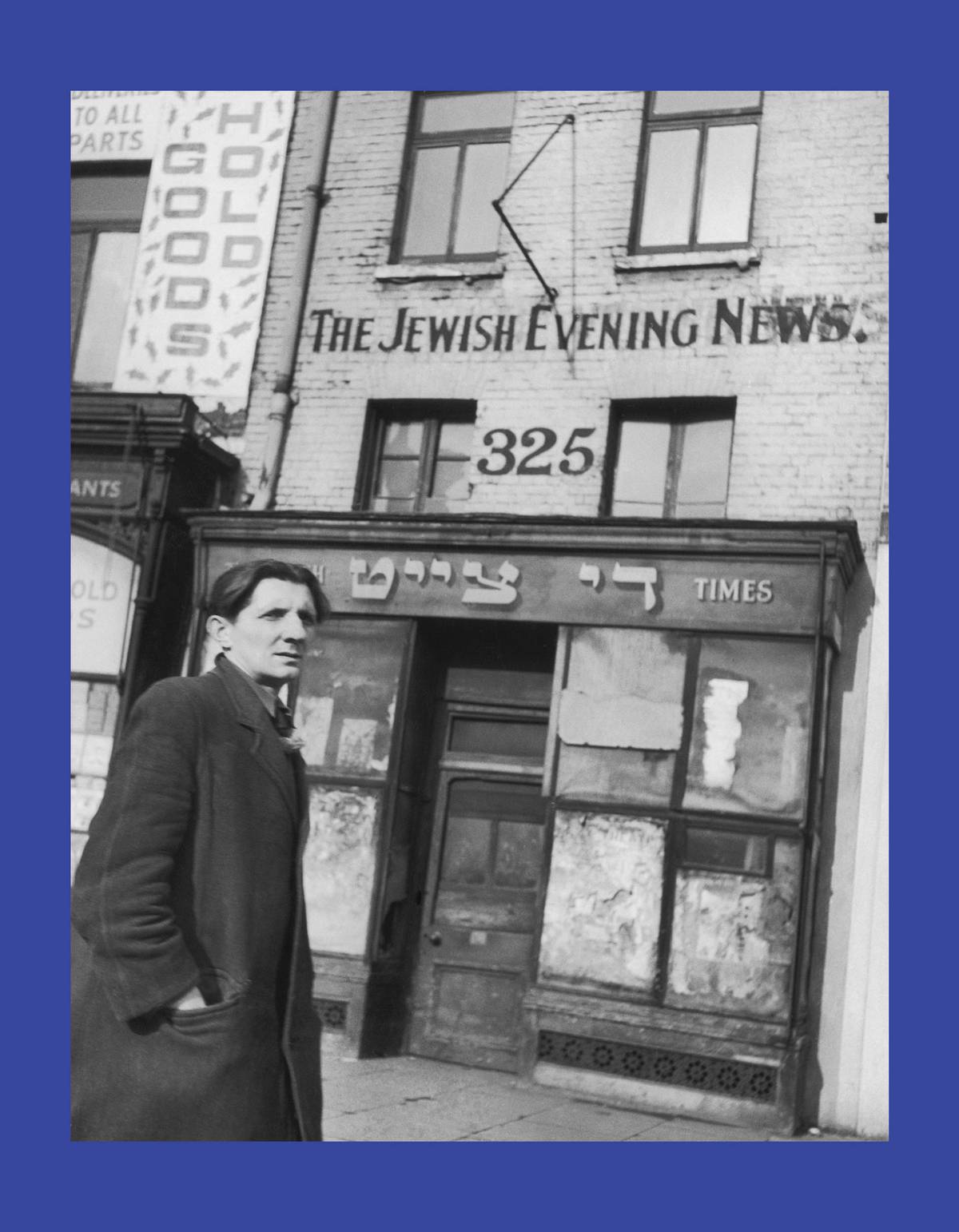

Strolling through London’s once-thriving Jewish quarter with the British novelist Will Self

“I don’t know what you want from me, I’m so fucking deracinated,” says Will Self, standing at the foot of the early-18th-century Christ Church Spitalfields, east London.

It is a warm late afternoon early last July that follows days of torrential rain. Self, dressed in a navy-blue cotton blazer and sky-blue slacks, smokes lumpy, hand-rolled cigarettes with no filter.

We move from the front of the church to a pocket park next to it. After taking our seats on a bench, we observe the relentless bidirectional flow of the nearly 2-mile-long Commercial Street, with its four busy lanes carrying traffic across east London.

Over 120,000 Jews, fleeing persecution in Russia and Eastern Europe, settled in the streets surrounding us in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They established a Jewish area that, by the turn of the century, became the area of England with the most foreign-born inhabitants. Across the following generations, the Jewish population departed gradually, as has almost every trace of their presence. We are preparing to visit the ghost landmarks of this vanished world.

The decline of the Jewish East End has an odd place in the annals of Jewish migration. This micro-exodus was not a tragedy. Jews were not compelled to flee by a central authority or a mob; suffering was not inflicted upon them in the process. Instead, it was a quiet story of upwardly mobile assimilation into a strategically inclusive English society.

Jewish movement away from the East End was gradual, and seemingly began as soon as the means for it became available. “Few people were so fond of the area that they didn’t want to get out of it,” observed editor and critic John Gross. It was also propelled by extraordinary institutions of Jewish self-help, such as the Jewish Free School, the largest school in Europe at the turn of the century.

The most lasting and consequential movement of the Jews who left the East End was to north and northwest London: Hampstead, Golders Green, Hendon, Barnet. The migration was described as the “north-west passage,” a term invoking the late-19th-century English desire to find a trade route through the Americas to Asia.

Will Self, the British novelist and political commentator, grew up with an American Jewish mother and an English father between East Finchley and Hampstead Garden Suburb. There, he had a front row seat to the transplantation of East End Jews. At Christ’s College Finchley, the kids used to describe their demographic—which was a third each English, Jewish, and Indian—as consisting of “the Yoks, the Yids, and the Pakis.” The Jewish third were all descendants of the Jewish East End.

“I grew up thick with the children of these people; cheek by jowl with them in the mode of their reinvention,” says Self. “I sensed their shtick even as a child. They managed to reinvent themselves as immigrant people who passed completely—and they got away with it.”

Was there any sense of the world from which their parents had come, any remnants of its cultural and verbal complexity?

“I was aware that the Jews around me had been in the East End, but fuck they had done a good job on purging that complex community. All the Jews we knew in the suburbs felt like dull English people. It was like: The shtick is not a shtick anymore; it’s a reality. We aren’t Jews anymore!”

Regarding the later Jewish migration into London in the 1930s, Self tells me: “The Jews are afforded two opportunities to perform this vanishing trick. And the second vanishing act retroacts into the perception of the first. It isn’t so much of an act because the first one was already underway. The class move has already been established, which is the essence of it.”

The true legacy of the Jewish East End, then, lies paradoxically in its disappearance.

In What You Did Not Tell, his transnational memoir of familial upheaval, resettlement, and memory, historian Mark Mazower depicts Golders Green in the 1960s as a blank site of epiphany:

“It was precisely Golders Green’s lack of history that had been the draw for others, that it was in this ultra-new suburb—with its thousands of houses built in scarcely a decade, with no one already there to claim prior ownership—that these newcomers to England found themselves most at home, most easily able to sink into the comfortable anonymity that they valued … The very names of its streets had marketed an anodyne vision of English pastoral to new entrants to the metropolitan middle class. From the start it had been a kind of survivors’ paradise.”

By the time Self was in his mid-20s, Margaret Thatcher’s second cabinet was initially a quarter Jewish, whereas from 1945-1970, there had only been two Jewish Tory MPs and dozens in Labour. (In the East End, said Thatcher’s early intellectual influence and speechwriter Alfred Sherman, a Hackney native, “you were born a socialist.”) The line of former Tory Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, that this cabinet featured “more old Estonians than old Etonians,” is testament to both the rise of Jewish status and the muttering nature of the conservative establishment response to it.

“I just wanted a cabinet of clever, energetic people—and frequently that turned out to be the same thing,” Thatcher once said. Jews were being propelled upward on the broader ideological tide of individualist aspiration. Thatcher flattered a sense of Jewish specificity while abstracting them based on those specific qualities.

“The key thing: We pass,” Self expounds. “We fucking pass. Note: I say ‘we.’ And the reason I say ‘we,’ is that whenever I tell an English person I’m of Jewish heritage they go like this [he tilts his head and puts on expressions of scrutiny and then recognition]: oh yeah. I’ve had this all my fucking life. As if the English—those legendarily polite English middle-class people—don’t think it’s weird to look at the size of a man’s nose and then pronounce on his ethnicity.”

Self detests ethnonationalism, yet he deems it inescapable. (He took a DNA test when reviewing Shlomo Sand’s The Invention of the Jewish People and discovered that, while he was 51% Ashkenazi, his father’s lineage turned out to include a surprise Balkan component.) This tension allows him to move across the boundaries of ideas and attachments, unmoored by identity—to reject narrow definitions and their opposites. He feels sorry for anyone who lacks this relation to place and belonging.

“I never think: I wish I felt more at home here,” he says of England. “I remember my father dying in Australia where he had emigrated, faintly mournfully saying, ‘I wish I could have a pint of Harvey’s bitter, in a nice pub in the lea of the South Downs.’ And it’s like: No, man, that doesn’t fucking cut it. He was dying in every sense. Shrinking down to this tiny datum. Like the inversion of Proust’s memoire involontaire: Everything condenses down to the madeleine rather than opening out of it.”

A lull in the conversation lets us know we have become absorbed by subject matter at the expense of motion. We set off back across the front of Christ Church, making the decisive turn from the main road onto Fournier Street.

Imposing white stone, buffering us from the noise and bustle of the present, establishes a different sense of time. We pass into an intricate web of small streets compressed with history, defined by cycles of communities and the rise and fall of economic fortune. Much of this area, sitting today in the shadow of the modern City of London, was established in the 18th century to accommodate Protestant Huguenots seeking refuge from persecution in France. Jews later established themselves as the vast majority here, in poverty, working as garment workers, cabinet makers, furriers, shoemakers, and so on.

The first shop sign after the Old Bells Pub, which straddles the opposite corner, reads “David Kira,” a reference to a family of Jewish banana salesmen. (The injunction on the church wall on the other side towers above us: Commit no Nuisance.) As is the case with the small number of other Jewish signs in the area: The sign remains where the people it was named after do not, even across multiple incarnations of the premises.

These Georgian terraced houses with their alternating autumnal bricks guard reservoirs of memory, even as the signs of the contemporary intervene everywhere: plastic alarm system shields fastened onto the outer house walls, inane street signs, little cards with bureaucratic recommendations wrapped around poles.

Once we arrive at the intersection of Fournier and Brick Lane, we are in full return to the present: glowing plastic, life in flux, the imbrication of peeling posters. Here we are flanked by the Brick Lane Mosque, which incarnates, and serves as a metonym for, the history of heterogeneous immigration in the area.

This building was first constructed in 1743 as the Neuve Eglise serving the Huguenots. By 1809, it was used by the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews; it then became a Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. It became Spitalfields Great Synagogue in 1898, after a group of Orthodox Jews established a breakaway synagogue in an outraged response to local adaptations of Jewish practice.

It became a mosque in the mid 1970s, following the arrival of immigrants from Bangladesh, who now form nearly half the population of the area. A minaret sculpture, added in 2009, is one of the most striking features: A sleek metal structure with an intricately textured surface, it stands on a block separate from the building.

Engraved above a sundial on the Fournier side of the mosque building is Umbra Sumus (“We Are Shadows”). This Horace reference, dated 1743 in the inscription, seems to have foreshadowed the limit of each community’s time here.

In the 19th century, the East End—then a public eyesore marked by poverty and crime, and sensationalized by Jack the Ripper’s local exploits—became a central focus of journalists, philanthropists, and social reformers. Its slums became targets of civilizing missions.

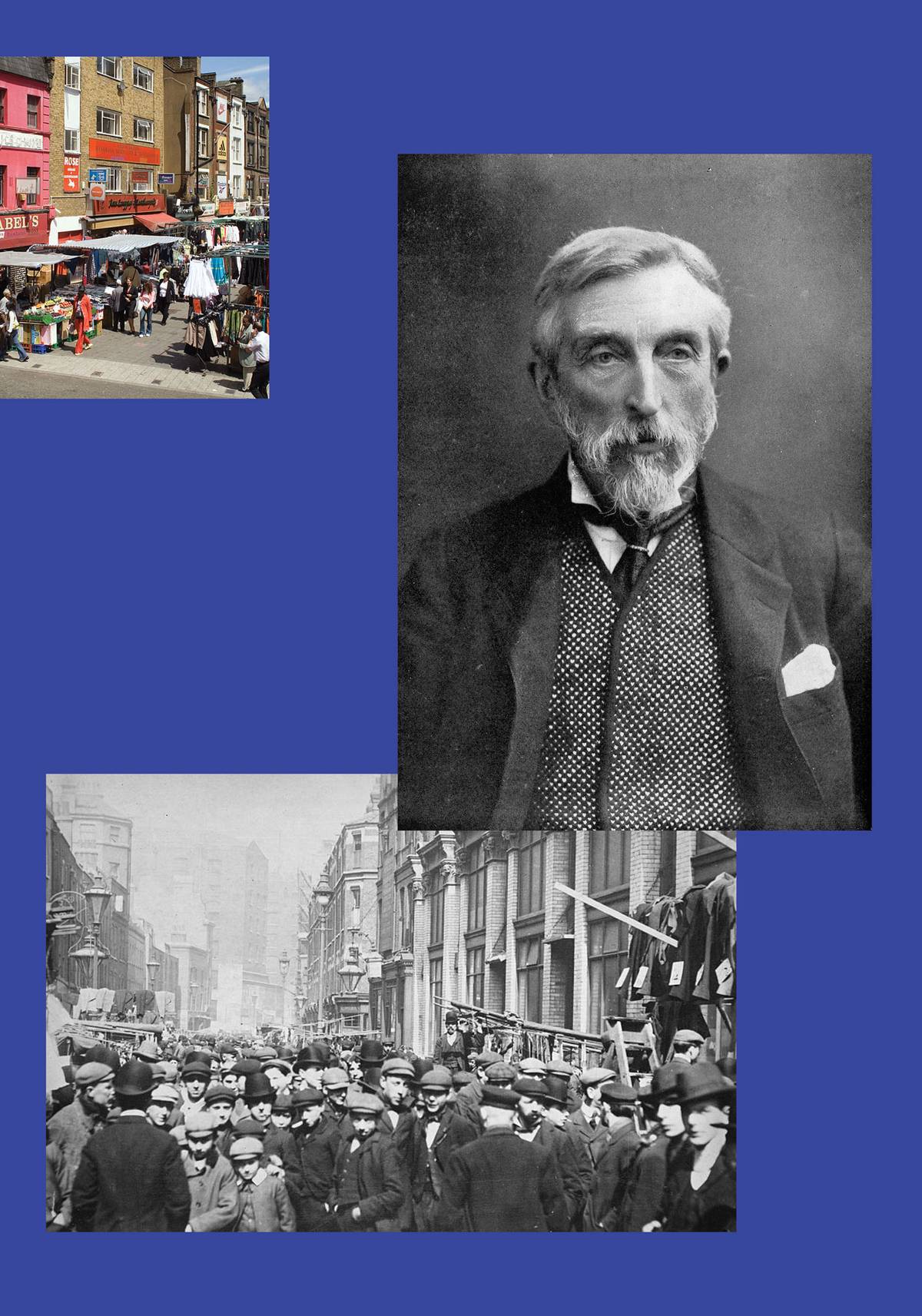

One major report into poverty in London carried out by wealthy businessman and urban surveyor Charles Booth spoke of “Jewish influence” being “everywhere discernible” in this area, of “the slow rising of a flood.” “No Gentile could live in the same house with these poor foreign Jews,” Booth proclaimed, “and even as neighbours they are unpleasant.”

But these descriptions, read in isolation, overstate the bluntness of Booth’s xenophobia. He also had a detailed sense of the relative utility of Jews within the broader project of English social reform and assimilation. Even as he noted that “people of this race” were “sometimes quarrelsome amongst themselves” (and enumerated many aspects of this internal quarrel), he also noted the potency of Jewish self-help, and the capacity of even “the most exclusive and backward” Jew to absorb “the environment of English custom and administration.”

Through her app, Zangwill’s Spitalfields, academic Nadia Valman narrates an encounter between Englishmen and Jews at this particular site of intersections. George R. Sims, a journalist writing in 1911, was fascinated by the internal hubbub of the synagogue here. He described a place “open night and day,” filled with “reverent and intelligent loungers,” since “the alien Jew has brought with him the old custom of making the Synagogue a meeting-place and a club.” For Sims, these “pious Jews, most of them from the lands of persecution and massacre” had “not yet learned the true meaning of English freedom.” Sims senses they are “nervous and fearful” of his presence; he is questioned in “broken English,” before a survivor of the Kishinev pogrom ushers him out.

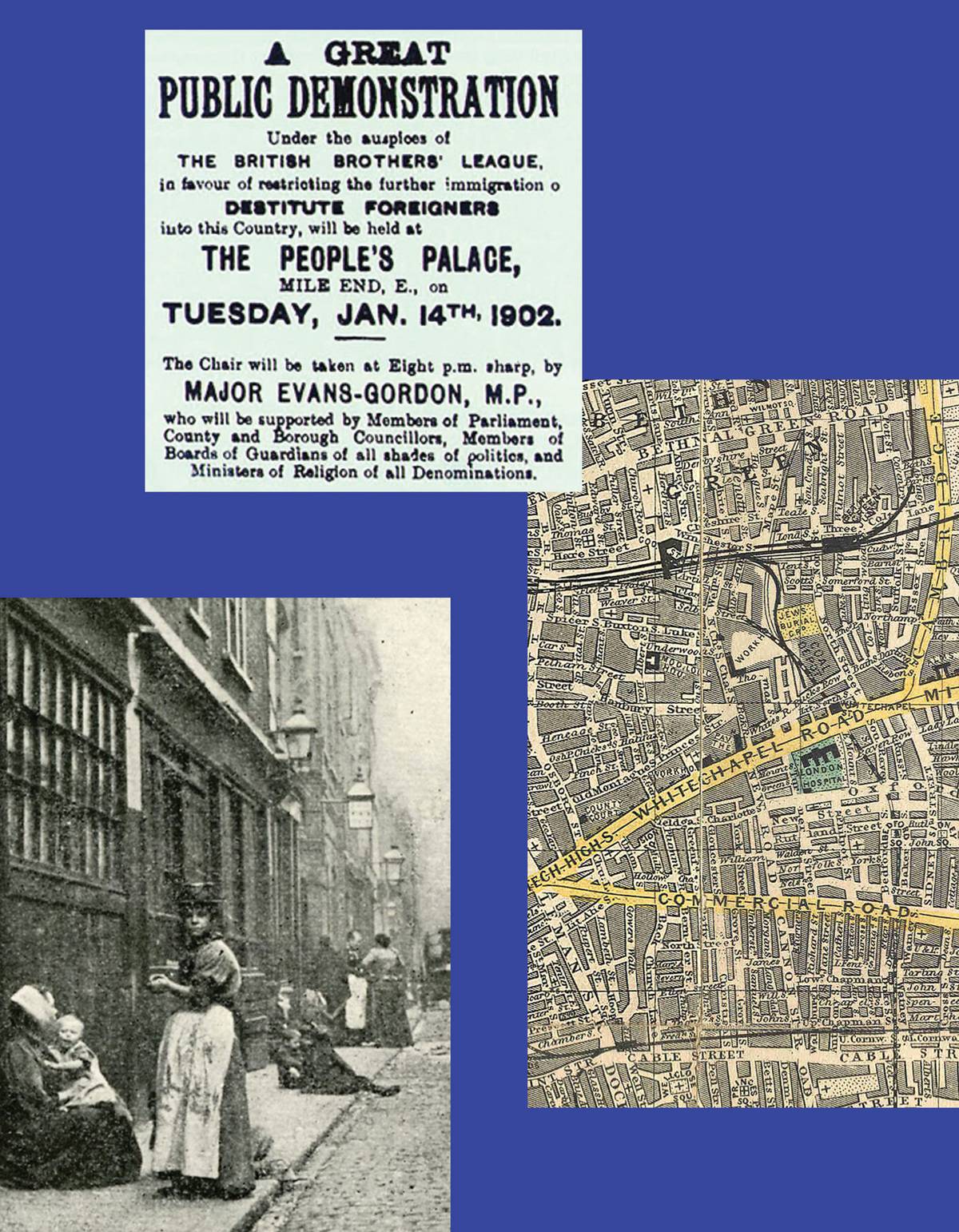

Valman describes the importance for poor Jews in the late 19th century of “not being seen to be a burden on the British state.” After the influx of Jews into the East End, wealthy Jews from the West End of London “feel as though the whole Jewish population is under scrutiny.” In this context, reasons for status anxiety included halts on immigration as represented by, for example, the Aliens Act of 1905, as well as the presence of far-right groups such as the British Brothers’ League. The presence of the Edward VII Drinking Fountain on Whitechapel, in tribute to a king whose close relationships with Jews advanced Jewish status in public life, was tantamount to a pitch to consolidate this nascent security.

The Jewish attempt to advance the assimilation of the East End Jews, therefore, was both a form of direct internal empowerment and a way to erase the external shonda that arose from their poverty in the first place. Valman depicts the dynamics within the Jewish community, such as the efforts of the Anglo-Jewish religious establishment and master tailors to combat socialism. At this junction where we stand now, cramped by the tumult of human traffic, tailors striking for better conditions would chant on the street, the noise crossing into the worshippers in the synagogue.

Self remembers how this transplanted dynamic manifested in the context of northwest London:

The secular Jewish culture in northwest London that I knew was an Ashkenazim pale of settlement culture. If you went to the Cosmo Café on Finchley Road, you’d see old Viennese ladies wearing fox fur and eating whipped cream on apple strudel. Now all you’ve got left are the mad frummers. With the marrying out in the community, over time, they win.

In these quintessential Spitalfields streets, like Fournier and Princelet, silence feels like a presence, not an absence. The space feels most populated during lulls in the day, when memory seems to resurface at will.

This area was largely in disrepair by the 1950s and ’60s, and began to attract obsessives who bought up homes and invested in their gutted interiors. Some of these homes are now boutique portals where the past is cultivated for its charms, efforts inspired by the simultaneities that are on offer here. An American named Denis Severs, for example, purchased a ramshackle house nearby and committed himself to transforming it into the imaginary home of an invented Huguenot family. Two decades after Severs’ passing, it remains open to visitors who must silently endure passage through the house, in which everything is modeled on life in the early 18th century.

Self’s steps resound on the Princelet pavement: There is a sudden intimacy to the way the sound settles along so many surfaces in such a small space. This closeness has been retained even as the street passed through cycles of poverty and prosperity. He dangles his glasses from his lip as he weighs up the sheer quality of the housing stock: the stately casing of doors and windows, the detailing in the panels and brickwork. I summon him to peer through the columns of space between the door panels of one seemingly vacant property, where a front yard filled with strange objects and tiles belies a rundown exterior.

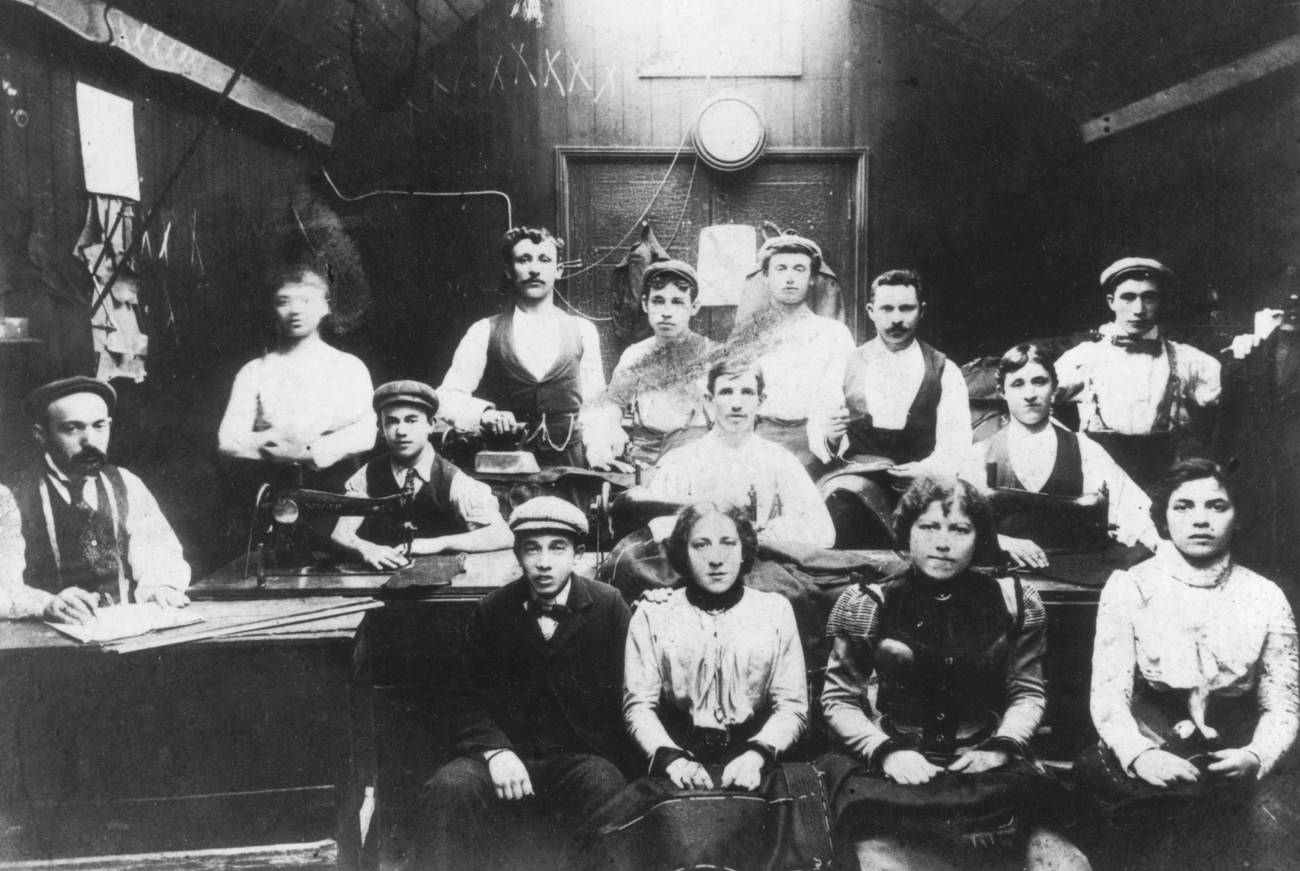

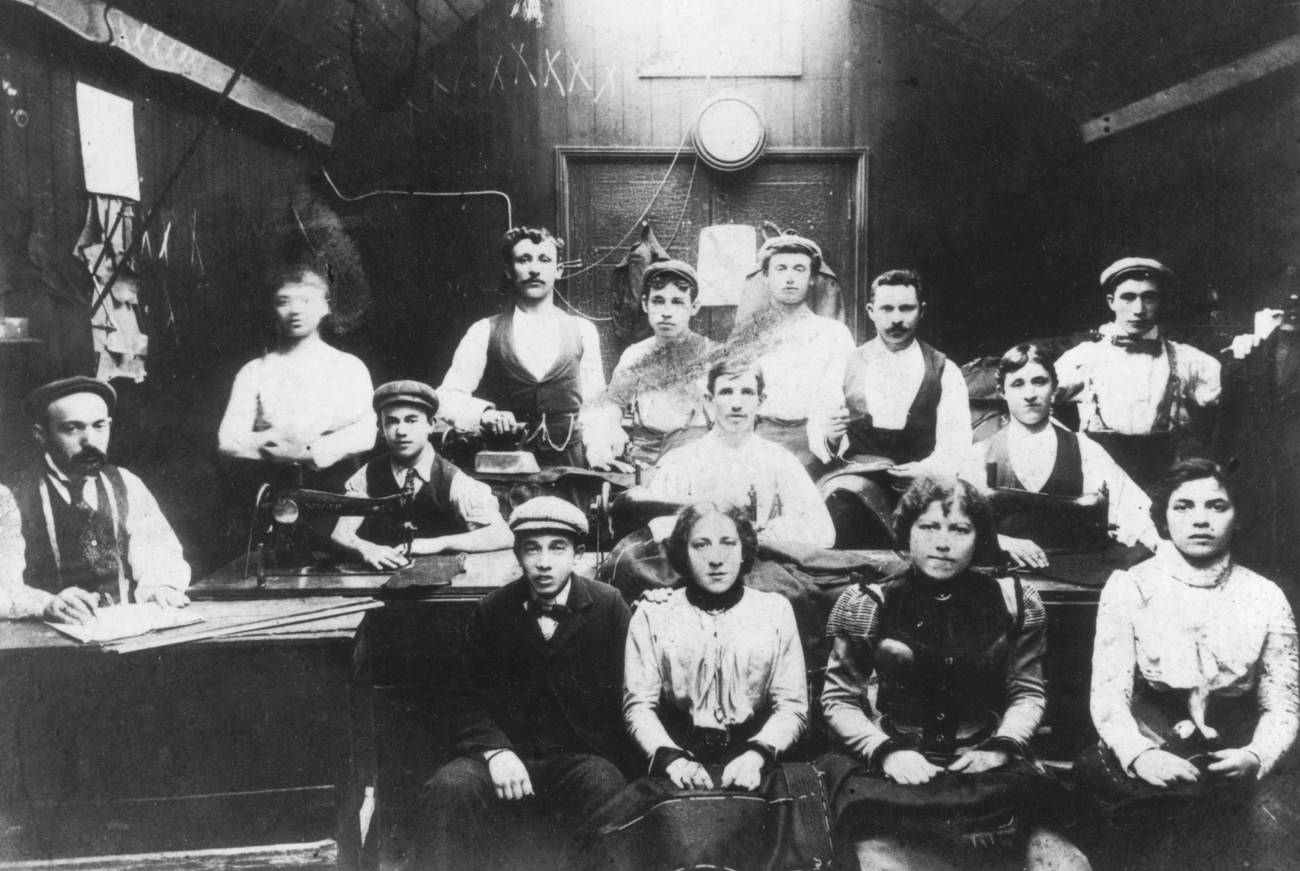

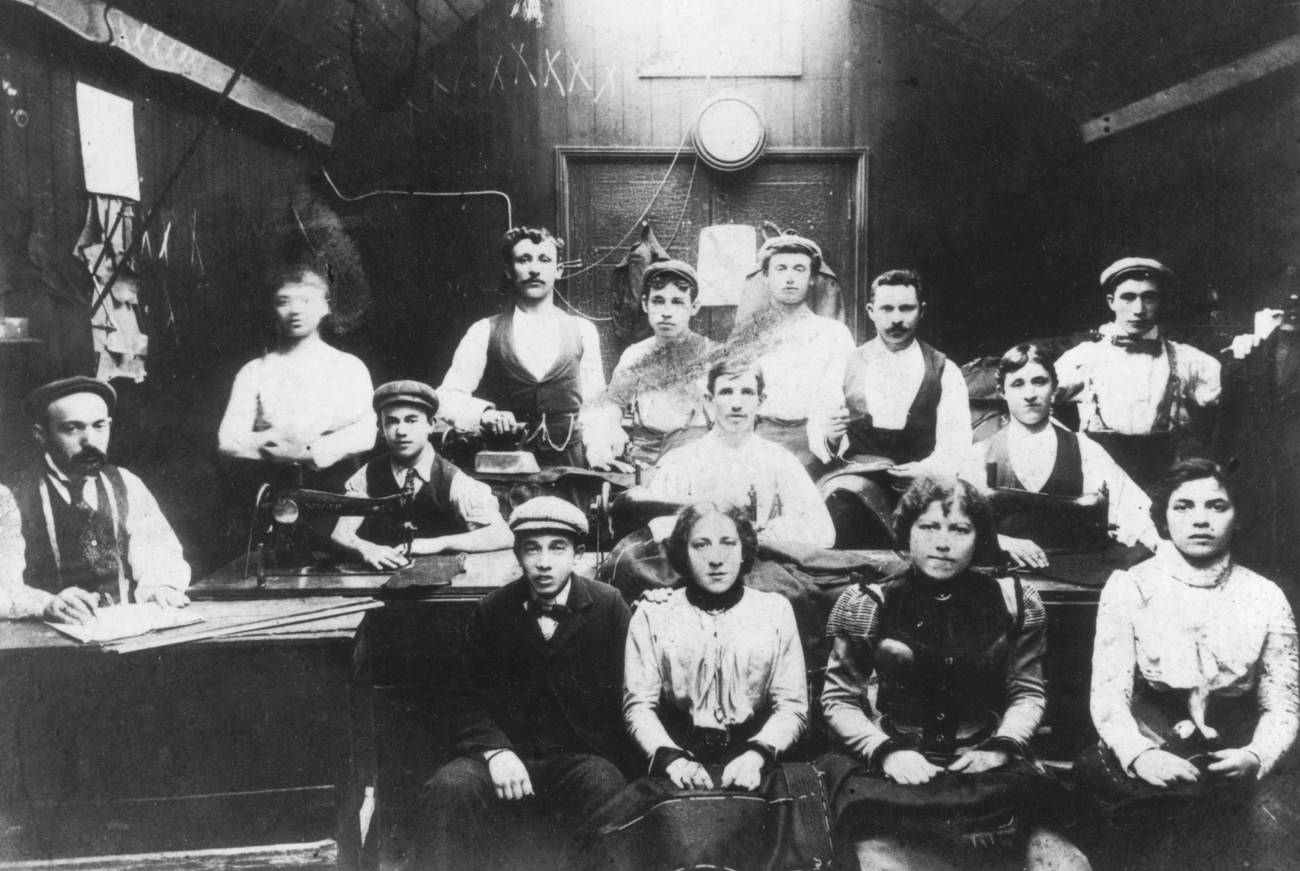

Valman narrates the socioeconomic dynamics on Princelet Street in the late 19th century, telling the story of the Jewish economy at a moment of transition. Today, on these Spitalfields streets, dotted with garment workshops, it is “not always easy to tell the difference between the bosses and the workers.” Many of the employers are themselves on the verge of ruination.

But on 17 Princelet Street, Mark Moses, head of the local tailors association and opponent of unions, is thriving. He employs 40 people: “machinists, basters, pressers, plain hands, apprentices, and buttonhole hands.” His daughter, Miriam Moses, who became mayor of Stepney and is referenced on a plaque here, became a galvanizing organizer in the area.

Rachel Lichtenstein, a sculptor and author whose paternal grandparents, immigrants from Poland, had a watch shop here, became spellbound by the Jewish East End and moved “back” to the area. Her approach to the subject is shot through with a trembling sense of the fragility of ancestral inheritance. There is a hypnotic isolation to her drive to complete the present by locating herself as fully as possible in the past. Her Jewish East End Memory Map, which lays out her reconstructions, research and collation of testimony, was an invaluable resource in my own navigations.

David Rodinsky, a reclusive scholar who “disappeared” in the late 1960s, lived here, above the synagogue on 19 Princelet Street. His room—strewn with scraps and scribbles, texts in various languages, and kosher food packets—was only accessed 11 years later, and it appeared even then to have been left unchanged. Hunting for traces of Rodinsky became one of Lichtenstein’s obsessions, even resulting in a book co-authored with Hackney mythologist Iain Sinclair.

His house is now the Museum of Immigration and Diversity, which, in a sort of parallel to the Tenement Museum in New York, aspires to frame the building as itself embodying the narrative of London migration. But it is not clear what Rodinsky’s place is within that narrative. His attic remains part of the story in an inert way; his disappearance subtracts him from coherence, renders him a nonsymbol. The sense is of an opaque project that has tried to tie up the loose ends of this space, but has only erected a monument to their failure.

We cut an eastward trail along Hanbury Street, where the time-burdened air of these streets yields to residential banality. Council estates recede on either side of the main road. The sky feels squat. The landscape: dumpsters behind railings; short iron fences in front of dark tower blocks; pavements impaled with bollards; craning, skinny lampposts in disjointed array.

At the far end of Hanbury, a three-story building fronted by an awning expanded over a strip of enlarged pavement was once the Brady Girls’ Club, made up of Russian and Eastern European Jews who lived nearby in “tiny flats with no bathrooms,” and run by Miriam Moses, daughter of Mark. Lichtenstein describes the Brady as a place that offered Jews “space, friendships, freedoms.” Activities included swimming galas, theatre trips, and camping holidays.

Concert parties, a social highlight, saw elaborate costumes and girls playing the parts of both sexes. But when the boys from Brady (the male equivalent club on Whitechapel) and the girls met up, one Brady boy recounted to Lichtenstein, “no wallflowers were tolerated” and “boys had a responsibility not to leave a girl standing alone.” A reference to elocution lessons at the Brady club interests Self in particular, sparking a flash of memory:

The woman who lived behind us in the Hampstead Garden Suburb, Ruth Rappaport, was my mother’s dream. She regarded Ruth’s uncle as a nebbish—he sold adverts for the Jewish Chronicle and wore a gray trilby hat. But Ruth, who had a prow of a nose and great tight curls, grew up on a huge Scottish estate and drove a car when she was 11. She was a woman, a psychiatrist, posh, Jewish—and she was English. It never got better than that for my mother, in identity terms.

“Nothing compared in brutality and degradation with the sights I witnessed in the East End of London,” wrote anarchist Emma Goldman, in a section of her autobiography that weighs the abjection of the East End against the universal nature of suffering under capitalism. Goldman had seen “drunken women lurching out of the public houses, using the vilest language and fighting until they would literally tear the clothes off one another” and children sucking on “whiskey-soaked” pacifiers. Without saying they were gentile, she implies the difference through Yiddish: “The Jewish children,” she noted, “called the women bummerkes.”

Alcohol was a fundamental cultural difference between Jews and gentiles. In a country with a profound drinking culture, and in a part of the city that became notorious in the late 19th century for overtly displaying the ills of alcoholism, Jewish sobriety was noticeable.

Dorset Street, a street so notorious for intoxication, violence and prostitution that it was eventually not only physically demolished but effaced from the map altogether, for example, was a gentile exclave within the Jewish enclave of the East End. By contrast, writing in 1879, Charles Dickens observed that among the Jews here, drunkenness was “an offence all but unknown.”

In his pained and comic memoir East End My Cradle, Willy Goldman wrote that Jews perceived the drunk gentiles as “obscene animals who squandered hard-earned money that should have been spent on their homes,” and that “by abstaining, the Jews proclaimed their independence as a racial entity.” “But [the home] wasn’t the only reason why Jewish men hardly drank,” wrote playwright Bernard Kops. “It was important never to let our guard down. Being always a minority, the home was the only safe place for us. We always had to be alert, doubly alert. To survive in foreign cities we had to be that much more sober.”

Pubs were gentile spaces. In the early decades of the East End, this manifested in direct territorial demarcations. But something of the spirit of the distinction lingered, and kept the self-annihilatory demands of English drinking at bay. Theatre director Steven Berkoff, who grew up in Stepney in the ’40s and ’50s, noted: “You see, we were of the café society and didn’t go to pubs … It was talk, talk, and more talk that governed our lives. We lived to talk and tell and communicate and reveal and kibitz.”

“Even in my childhood and into the 1970s, it was the self-perception of Jews that they don’t drink,” Self tells me. “When I got in trouble with booze, my mother said: You can’t be an alcoholic, you’re Jewish. You’re Jewish enough not to be an alcoholic.”

On the north side of Vallance Road, we come across Hughes Mansions, one of the many projects of the Industrial Dwellings Society, established by Nathan Rothschild and others to allow (mostly) Jews to live in better conditions. Here, 134 people (120 of them Jews) were killed in the final German V2 rocket attack on London in March 1945. Miriam Moses, who was a first responder, dispatching assistance from the Brady Club, completed the arc of Jewish self-help. A nearby plaque, with no allusion to Jews specifically, commemorates the attack.

The war seems to have affirmed a sense of Jewish identity as well as uniting Britons and Jews through mutual purpose and commitment in fighting Nazism. The bombings, however, physically blew apart the world of the Jewish East End. Evacuations lurched forward the process of leaving.

We walk southward down Vallance before turning onto Old Montague Street, heading back toward Christ Church.

Within the current urban topography, Old Montague Street is still a “central” street: It cuts a swath through the area. But it is difficult to summon the old, different centrality it had, when historian Raphael Samuel described it as “the nearest thing in the East End to the way I imagined a shtetl.” There were a wealth of shops here that served local Jews, and indications of the interconnected Jewish life that had started in the late 18th century everywhere. Lichtenstein lists a cigar factory, cinema, restaurant, library, dressmaker, barbers, sweetshops, kosher butchers, a matzo oven at the back of a pub.

Old Montague Street was greatly harmed due to wartime evacuations and postwar clearance and rebuilding. Today, behind wide pavements, residential clusters recede into the space beyond this quiet central street.

The Rothschild buildings, some of the most important projects of the IDS, were located nearby, and were demolished during the 1970s. The entrance arch for those buildings, though, was taken and placed here, at the forecourt of an unrelated council estate complex a few minutes away. It sits puzzlingly at this site of non-Jewish residence—not particularly decorous or kempt, with a small description attached, but no particular reason why anyone would care. We stare at the sign together, while someone passes through the gate, having a conversation with someone behind an open window in Bengali.

The Kosher Luncheon Club was one of the few functional Jewish establishments when Lichtenstein gave tours of the area in the early ’90s. She writes of how it provided her a kind of respite as a guide, allowing her to pep up her tour group by pointing to a Jewish landmark that retained Jewish life, instead of symbols and tokens of disappearance. It was described as the kind of place where they’d put their thumb in your soup; where you had to specify you wanted a fresh cup for your tea. Once a bustling meeting place, the club dwindled until it became merely a register of the decline of Jewish togetherness in the area. It was finally closed in 1994, two years after a series of attacks by neo-Nazis. Now it is a nondescript set of flats and offices.

We arrive on the corner where the club used to stand, struggling to figure out whether Greatorex Street, which sounds to me like an outdoor clothing brand, is Huguenot or Anglo-Saxon, when two excited women, walking in the opposite direction to us, recognize Self, and say they love his books. The discussion almost immediately turns to our location. The other woman, who is from South London, asks if Self lives there, having perhaps picked up on the numerous citations of Self’s residential location in profiles.

“I’m stuck down there,” he says, and their knowing and sympathetic response—“I know, you’ve been there for a long time”—suggests the comment was redundant. They list some of the various communities in the area approvingly—but Self stops them at the Portuguese, his tone becoming chastising as he laments their transience: “They don’t stay, though.”

He introduces me and points to my parted portfolio of documents, accounting for our presence: “We’re doing the old Jewish East End sites. I’m nominally of Jewish heritage, but I don’t know anything about it at all.” Both women turn out to have done the tour many times. They mention a little church on Brick Lane, now a primary school, originally built by Jews, where there’s still a hidden Star of David that no one can find; I haven’t heard of it.

“We’re all building our knowledge of country,” Self concludes.

As we continue down Old Montague Street, we end up at the intersection where the original location of Bloom’s deli stood. Bloom’s, which had another branch on Whitechapel (now a Burger King), eventually moved northwest along with the community, and Self remembers visiting the branch in Golders Green. The East End Bloom’s, seemingly never renowned for its food, closed in 1996.

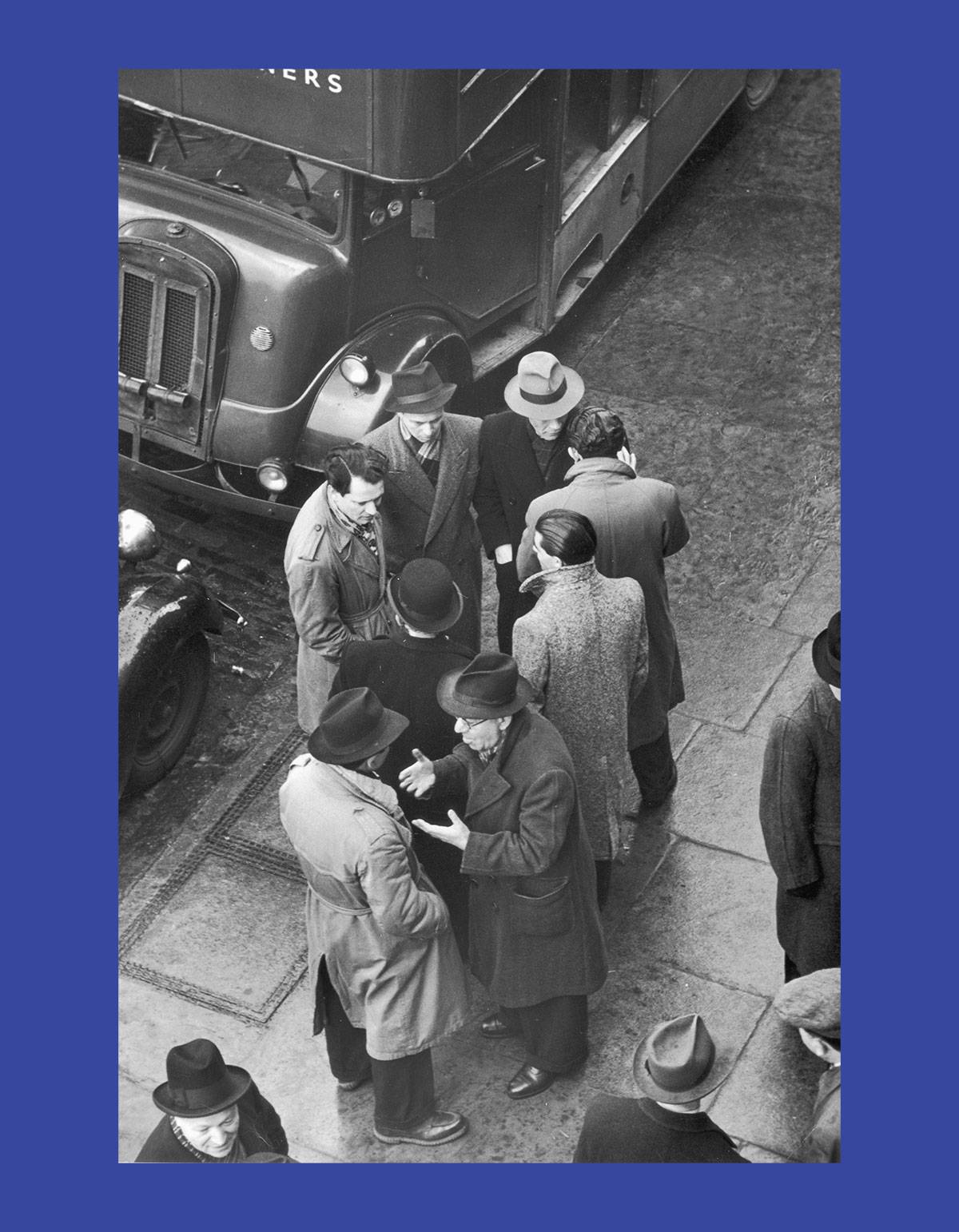

In a world where “the teeming streets sheltered the family,” Jewish life would flow from cramped apartments to crowded pavements. Outside Bloom’s on Sundays, Jews would meet to argue politics. Communism, socialism, anarchism, and Zionism all had their time here. Each presented Jews with the argument that their individual responses to poverty, and the ideological questions of solidarity and assimilation, meant their fate was tied to the resolution of grand conflicts between ideas. But while Jews here shared Yiddish folkways and a European recent past, and their attachment to those places and the struggles that defined them were potent, the echo of those experiences inevitably became increasingly distant.

What rose in its place was England, which offered a new pathway for existence: salvation through politeness, property, the rule of law, away from abstraction and toward the all-encompassing conception of “common sense.” At this juncture, England offered the freedom to discuss grand struggles, but by providing remove from them, drained them of their vitality.

“Men stood around everywhere, anywhere, outside the kosher restaurant or the Turkish bath, or the Labour Exchange,” wrote Kops. “Arguing was their occupation and you would have thought that they would soon be hitting each other—but instead they’d pat each other on the back and most reluctantly tear themselves away as midnight approached.”

Going out in order to be together runs contrary to how space works in this city, which is regulated and regimented, delimited by function. Everything that matters happens behind closed doors. I ingest the silence here, and think of the suburbs.

Petticoat Lane (on Middlesex Street) now stretches before us. The smell of dull, stale rancidity that is oncoming surely does not compare with this place in its heyday, when Zangwill described how “every insalubrious street and alley abutting on it was covered with the overflowings of its commerce and its mud.” This was a place where, as cartoonist Harry Blacker wrote, “the cries of the vendors, the chatter of the shoppers and the sickly sweet smell of rotting vegetation, acted as a homing beacon for the natives.”

Once perceived as an unruly zone of chaos by the authorities, it is a more effectively regulated place today. But there has been continuity from the Jewish era: this place still sells shmatter. Stalls have been stripped down to their frames now. Fragments of the day’s market—plastic, tape, paper and cardboard—are strewn across the floor. Motes of detritus drift through the air.

“The Lane” is one of the few places in the East End to which Jews seem to have returned well after having undertaken the northwest passage. Here, Willy Goldman wrote, “nothing was ever sold without words,” and something of that verbal life lingered in some form. Self remembers being taken here by his mother as a child, catching the tail end of the old market culture: “The costers were known to be the most vocal of all the markets. They would whack down these huge rosettes of crockery: I’m not asking for a five bob! There was a whole shtick, a whole performance.”

This shot of Thatcher making a purchase at packed local deli Mossi’s, featured in a documentary, somehow completes the picture. “I never saw Maggie put her hand in the barrel and shlep out a herring or a cucumber,” one East Ender recalled—in that nontactile exchange, she isolated commerce from culture, affirming the logic of capitalism and pointing the way forward to how it might animate and shape the whole of life.

We peel off to Goulston Street, where Zangwill described a “pandemonium of caged poultry, clucking and quacking and cackling and screaming” at festival times.

Outside the corner store, a girl sits on a stack of magazines with her back against the wall, her bare feet nodding to the Drake tunes playing out of an open window above the row of shops. I turn back halfway down the quiet street to an unimpeded view down Bell Lane, sweeping upward to the skyscrapers of the City in the distance.

To our west once stood the Brunswick buildings: tiny, overcrowded, fetid apartments housing Jews from various countries. Lichtenstein notes that the design of the bathhouse opposite, the first public baths in London, was “considered world leading and helped lead to the ‘Baths and Washhouses’ Parliamentary Act of 1846, after which many other public baths were constructed following its model.” After I relay this trivia, Self recalls his experience in the shvitz in Westbourne Grove, northwest London:

“There were old Jewish cabbies—another lost culture—and they’d be sitting around, eating jelly and drinking milky tea. You’d lie on a slab, and they’d dip the grass skirt into soapy water and rub it vigorously over your body, doing it as a team in the heat. And if you don’t take your turn with the schmeiss: ‘He’s a fucking schmeissponce, you don’t want anything to do with him!’ And it’s all very sexual and homoerotic.”

Having looped back, we are in the middle of a constellation of the great self-help institutions of the Jewish East End. There is an abundance of glass ahead of us, an intense feeling of windows glaring at each other in close quarters, with the Chicagoan projection of 155 Bishopsgate in the background. Here in this delta of streets between Bishopsgate, Commercial Street, and Whitechapel, the lack of activity is offset by the rumbling of the greater significances beyond it.

The Jewish Board of Guardians was based here for 50 years from 1896, commemorated on a plaque on a widely fronted cocktail bar on an otherwise quiet, inward facing corner. According to East End writers, it was a complex presence, even in the context of self-evident material need. The shame that rich Jews felt at the East End was mirrored by some of the narrators on the receiving end of their designs.

Kops writes that his mother, for example “hated to be seen” taking him to receive clothing, “handed down by wealthy Jews the other side of nowhere.” At one point in Emmanuel Litvinoff’s memoir Journey Through a Small Planet, the writer is filthy, flea-bitten, hungry and directionless, yet still has to be persuaded by a Welshman to walk over to the Jewish Board of Guardians to replace his destroyed shoes. “According to our folk,” the narrator reflects, “the worst thing that could ever happen to a human being was to become the recipient of charity.” “Boots is not charity, you’re entitled to boots,” the gentile says, seeking to replace the protagonist’s prideful anxiety with a rational approach to his material options.

The Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor, now converted to apartments, still has its memorable terracotta arts & crafts style sign designed by Lewis Solomon, which includes the Jewish date of its founding. The “Way In” and “Way Out” signs affirm the processinglike function of the space. As Valman writes, “the structure of the building shows an intention to control its disorderly clients, by firmly steering their movement through it.”

Dynamics and attitudes surrounding the kitchen were also complex. Kops writes of the Jewish resistance to charity offered by other Jews—the “strange snobbery” that persisted “even though we were all in it together.” A friend stopped talking to Kops after spotting his dad eating here; the way around this spectacle was to take the soup home. Dismal silent footage from 1934 shows men queuing up for their soup, angling their faces away from the camera.

As we pass the Bell Lane entrance to the Jewish Free School, I channel Zangwill, who saw, even in the tumult of Jewish life here, the gradual way that “respectability crept on to freeze the blood of the Orient with its frigid finger, and to blur the vivid tints of the East into the uniform gray of English middle-class life.” His topographic, panoramic perspective on Jewish assimilation was rooted here:

“It was the bell of the great Ghetto school, summoning its pupils from the reeking courts and alleys, from the garrets and the cellars, calling them to come and be Anglicized. And they came in a great straggling procession recruited from every lane and by-way, big children and little children, boys in blackening corduroy, and girls in washed-out cotton; tidy children and ragged children; children in great shapeless boots gaping at the toes; sickly children, and sturdy children, and diseased children; bright-eyed children and hollow-eyed children; quaint sallow foreign-looking children, and fresh-colored English-looking children; with great pumpkin heads, with oval heads, with pear-shaped heads; with old men’s faces, with cherubs’ faces, with monkeys’ faces; cold and famished children, and warm and well-fed children; children conning their lessons and children romping carelessly; the demure and the anaemic; the boisterous and the blackguardly, the insolent, the idiotic, the vicious, the intelligent, the exemplary, the dull—spawn of all countries—all hastening at the inexorable clang of the big school-bell to be ground in the same great, blind, inexorable Governmental machine.”

Self acknowledges the power of the passage, but points to its vast scope as a sign of its limitations. “It’s enacting what it is: The impact of life in the metropolis forces the human psyche to become a tabulator,” he says. “There’s too much stimulus. You create a list that feeds itself into the very Moloch that it’s created.”

As we approach the end of our walk, and I have unburdened myself of the circuit of knowledge of the Jewish East End that I have accumulated, I can feel a refreshing, unsettling return to ignorance.

“Anglo-Jewry itself was not interested in the East End as a location of memory, until it was almost completely lost,” Valman told me. “The establishment narrative was that the Jews were in the East End temporarily, and that is why it was an object of shame—of flight and embarrassment—rather than something embraced as a constituent of Jewish identity.”

I was drawn by the historical silence as much as the physical silence of the Jewish East End. The question of why the Jews left is answered by every current of logic moving in the same direction. But the drive to frame the decline of this world as inherently and uncomplicatedly positive troubled me, as much as passive nostalgia dissatisfied me. I was not content to look backward. I was distressed that this world had its own demise baked into its existence—that it couldn’t retain more of itself and evolve instead of vanishing completely.

In an unflinching article, historian David Cesarani focuses on the 1930s, the period during which the London-born Jewish population became the majority within the East End. He uses the bitter novel Jew Boy by Simon Blumenthal, which focuses on a generation “suspended between the debased and denigrated Yiddish culture of their parents and the culture of England, a society which was none too welcoming to them,” as the basis for his edgy investigation.

Cesarani’s discomforting approach attacks the core identity and narrative of the East End as a site of continuity built on a holistic transmission of a Jewish way of life. Instead, he depicts a fragmentary and chaotic period on almost every level of life, with young Jews both “stigmatized by the majority society” and “unable to find solace in Judaism or leadership within the Jewish community.” Organizations like the Board of Deputies failed to recognize the needs and aspirations of younger Jews, which showed itself painfully in Anglo-Jewry’s supine response to local fascist organizations.

Jewish East End literature contained some of these rogue perspectives by registering the slow tide of assimilation: both its inevitable force and the friction of resisting it.

Roland Camberton (born Henry Cohen), a novelist who vanished in the early 1950s after publishing two novels, writes of punctual worshippers: “If they were scheduled to begin service at nine o’clock, they began at nine o’clock, or even—to show themselves more English than the English—at ten to nine.” But Kops writes, by contrast, of the jubilant dancing at his sister’s wedding, when he felt “that the veneer of England and Europe was very thin upon us.”

John Gross’ memoir A Double Thread (the two threads being English and Jewish) is a specimen of the moderation of the Jewish sensibility. “It would be as wrong to deny the significance of the last scraps of inherited Yiddish as it would be to make too much of them,” is pure English prudence.

But there are also moments that convey the contortions that assimilation requires. Litvinoff, who did not describe himself as English and was famous for reciting a poem critical of T.S. Eliot’s antisemitism in front of the poet, wrote: “I tried to remember to not talk with my hands, but the moment I got excited they jumped out of my pockets and made un-British gestures. When I shoved them out of sight my tongue stumbled on the simplest phrases.”

In Self’s early story, “The North London Book of the Dead,” the narrator, who had always expected his mother to outlive him, goes through an “intense depression” at “having lost an adversary” when she dies. But after she is interred at Golders Green crematorium, he encounters her again in a Crouch End flat similar to the one she lived in, where she is still a “crushing snob about where people lived in London.” This was the city as a kind of internal continuum, a metempsychosis trap.

Growing up, Self—with his family connection to America and intellectual and literary connections to Europe—assumed he would leave London eventually. But after his mother died and his father and brother emigrated, as he told editor Claire Armistead, “I realized it wasn’t that I wanted to leave London at all, I just wanted to get away from my family. So I stayed.”

Even though Self once said that London was inseparable from his fictional project, he is not quite a “London writer.” His attachments are to London’s anarchy and its miasma. He resists reverential circumscriptions of community and place. Nor does he find the possibilities of London writing inexhaustible in their metaphysical depth, drawing the line at “claims to a form of mythopoesis that in some sense will transcend the material.” He is suspicious of seeing gnosis in the city, believing arcana are encrypted in it. “There’s a perversity about seeking communion in a city,” he tells me. “Only occultism or ethnonationalism could lead you to expect it.”

While Self inserted alien elements into a tradition of novels set in London, he did not anchor his sensibility here. Self’s focus on Outer London allowed him to explore one of his essential preoccupations: the relation of the psychological and cultural margin to the core.

He would replace getting out of his head with going out of town. Inspired by getting clean, his “radial walks” to the “interzones” on the periphery of the city became a new way to investigate the inner/outer dynamic. This hunger for expansiveness eventually extended to places that were not physically contiguous: leaving his house in Stockwell, walking to Heathrow airport, flying to Los Angeles, and then walking to Hollywood from LAX, for example. His trip to New York chronicled in Psychogeography was charged with a roving, dissatisfied curiosity about his mother, who “spoke little of her childhood and was profoundly uneasy about her Jewishness,” and contained minidramas of place and belonging in relation to his other country of citizenship.

“I hold a U.S. passport; I’ve lived there. I feel no more American than I do English,” he says, as we pass along the Spitalfields arcades. “The part of me that doesn’t feel English used to hearken to America: muscle up to the bar and say hi! to the guy next to me, and think: maybe this is gonna work. But it didn’t, really. Again, it’s the nationalism; I can’t cope with the nationalism.”

Today, he feels that he wants to leave London, and that this stance reveals something about his fundamentally unsettled status within England.

As evening approaches, we find ourselves in the midst of marching England soccer fans. They are on their separate paths to one pub or another, to watch a knockout semifinal of the European Championship against Denmark. The frisson of common purpose and stakes has charged the day: There was an excuse to drink earlier, to talk to strangers more freely. Now the urgency is palpable: Voices are rising along with the pace of movement.

English soccer has rhetorically embraced progressive ideas, and has made strides in establishing a multiracial constituency for the English flag, which, during the peak years of football hooliganism, became tainted by association with both reflexive smallness and violent expansiveness. When England fans first booed the anti-racist, knee-taking gesture the team performed in the warmup games for the tournament, a rupture appeared in the new progressive narrative.

Self is not a sports guy; he wasn’t aware of the game. But he is aware of the debate surrounding the team, and once I expound on some of the conflicting dynamics, he gets more excited about the evening walk he had planned with his son. They had prepared to peruse Brick Lane—its shadowy lanes and brightly lit interiors—but now there was a different phenomenon to observe. They would search out the pubs—not to drink within, but to look into from the sidewalks. Instead of watching the game, they would watch the English.

Mardean Isaac is a writer and editor based in London. Educated at Cambridge and Oxford, he has written for publications including the Financial Times, Lapham’s Quarterly and New Lines magazine.