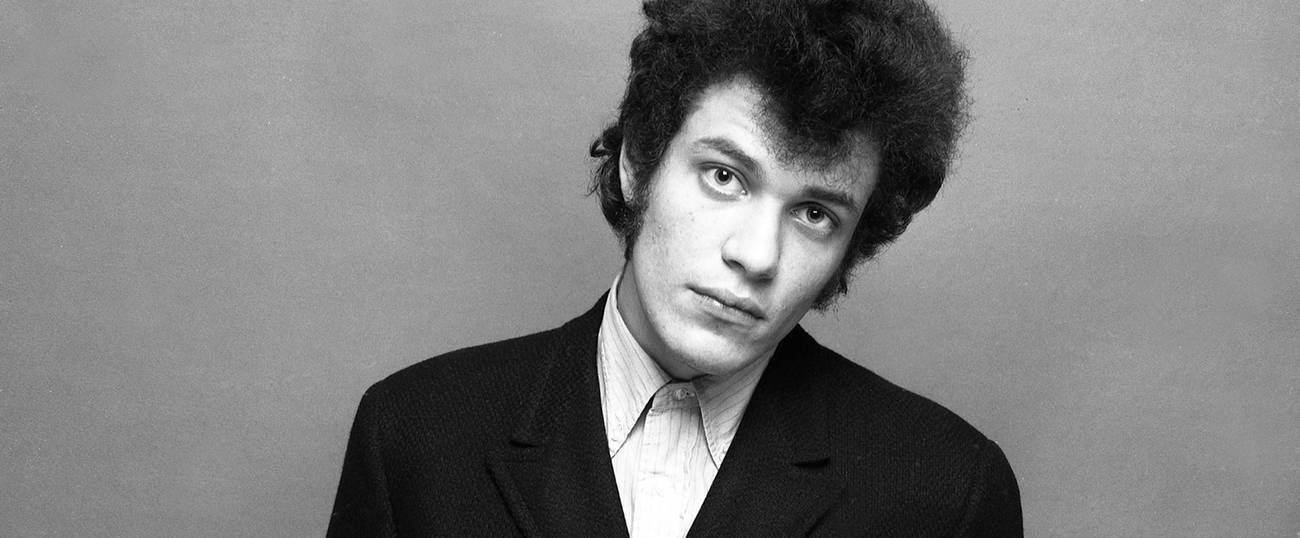

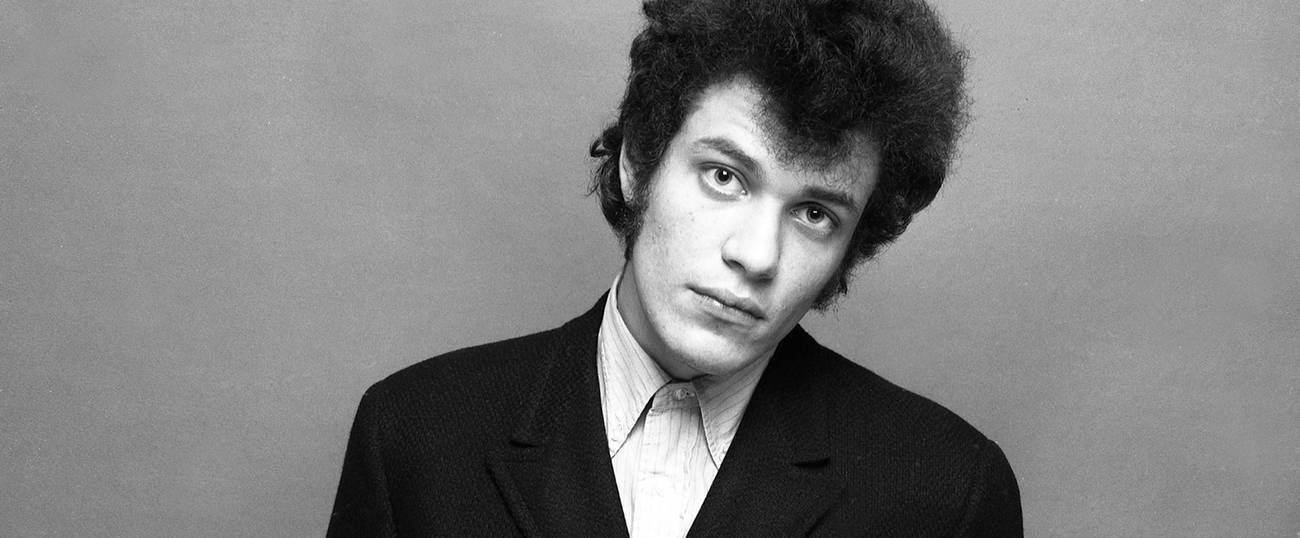

Jewish Guitar God Mike Bloomfield’s Blues

A revised and updated rock bio explores the influential and tragic life of the underappreciated riff master

In 1977, Michael Bloomfield performed at McCabe’s guitar shop in Santa Monica, California. The man who, between 1965 and 1968, had been the future of blues music was settled in semiretirement. Late in the set, he played a blues riff and sang: “I’m glad I’m Jewish, I’m glad I’m Jewish. Hebrew to the bone, Lord, Lord, Lord.” The audience laughed and Bloomfield later refrained: Judaism “kept me strong all my life.”

The song is jokey in nature, but it poses the question: How does one talk about Michael Bloomfield without talking about him being Jewish? Just as one might ask: How can one talk about the man, whose melodic and furious playing set Bob Dylan’s music alight, without mentioning his fear of fame, heroin addiction, insomnia, and mental anguish?

Rock author Ed Ward explores these issues in Michael Bloomfield: The Rise and Fall of an American Guitar Hero, in order to give a warts-and-all portrayal of the man Eric Clapton described as “music on two legs.” This Chicago Review Press edition is a revised version of a 1983 release and includes new interviews, as well as the extensive 1968 interview Bloomfield did with Rolling Stone co-founder Jann Wenner. It also includes an extensive 59-page discography.

Ward’s gravamen is laid out in his opening chapter, “The Devil and Robert Johnson,” in which he argues Bloomfield’s decline bears similarities to that of the original Delta blues singer. He writes:

An intelligent, well-read man from the Jewish upper middle class could not possibly share even a modicum of the experience that haunted Robert Johnson, or so we tell ourselves, and to sell one’s soul to the devil, one has to believe that the transaction is possible. Michael Bloomfield was not Robert Johnson. That is not the point of the story. But his identification with Johnson’s fear was real. So was his concern for his soul. Let’s just put it this way: Satan is irrelevant to this story; Robert Johnson is not.

***

Michael Bernard Bloomfield was born July 28, 1943. Raised in Glencoe, a wealthy suburb on the North Shore of Chicago with a large Jewish population, his father, Harold, was a successful industrialist and his mother, Dorothy, was from a Czech family of artists. For his bar mitzvah, he was given a portable transistor radio. The kid who struggled at school and rebelled against authority found comfort in black music on the airwaves. He would later remark: “I was just a product of the radio, and all I wanted to do was imitate radio as fast as I could.”

As a teen, he worked in his grandfather’s pawn shop, which gave him the chance to play on guitars hanging in the window. Despite being left-handed, he forced himself to play right-handed—and by 15 he claimed he was a “great” guitarist. Ward writes this was “the sort of statement that one takes with the proverbial grain of salt, except, in this case, he just happened to be telling the truth.”

As a teenager, Bloomfield ventured to the black blues clubs on the South Side of Chicago with his family’s maid and quickly began playing with artists like Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, and Howlin’ Wolf. He said: “I would go down there thinking I was really some hot stuff, you know, ’cause I had some fast fingers and I had plenty of licks, but I didn’t have no soul or nothing. All I had was that speed and some brash Jewboy confidence.” Brash Jewboy confidence or not, his talent was recognized by his heroes, and the late Muddy Waters told Ward: “When I first heard Michael, I knew he was gonna be a great guitar player. I let him play with me all the time, sit in with my band. … As a guitar player? One of the greats!”

In March 1964, aged 21, he was signed by Columbia. John Hammond, who was the first to record Billie Holiday and Bob Dylan, was given Bloomfield’s demo in New York and flew to Chicago to sign him. During that visit, Hammond saw a friend, Rabbi Edgar Siskin, who asked what he was doing in Chicago. The rabbi raised an eyebrow upon hearing he was there to sign the boy whose bar mitzvah he had presided over. But Hammond was unsure what to do with Bloomfield because of his lack of singing ability. “He could not have competed with the Rolling Stones,” Hammond told Ward. “He was no Mick Jagger, but he was a hell of a guitar player.”

Aware he would be unsuccessful as a frontman, Bloomfield joined America’s first interracial blues outfit, The Paul Butterfield Blues band. He showcased his breakneck improvisation and melodic phrasing on their eponymous 1965 debut album and 1966’s East-West. “When I’m playing blues guitar real well,” Bloomfield told Rolling Stone in 1968, “that’s when I’m not fooling around but I’m really into something—it’s a lot like B.B. King. But I don’t know, it’s my own thing.” Carlos Santana told Ward he “used to wait” for Bloomfield to solo in anticipation. “Just the way he put his finger on it,” he said. “You get a chill and it gets you excited.”

***

Bloomfield met Dylan in 1963. He left enough of an impression for Dylan to call him two years later to ask Bloomfield to play on his Highway 61 album. Ward describes this record as changing “the course of popular American music”—and Bloomfield’s performance with Dylan at Newport in 1965 “would mark a turning point in the history of electric guitar.” He adds: “It’s not hard to understand why some people in the audience were confused, because what Bloomfield gave them on the evening of July 25, 1965, was the future of rock guitar.” Dylan wanted Bloomfield to join his touring band full-time, but Bloomfield wanted to stay with Butterfield as a bluesman.

But relentlessly touring with Butterfield was too much, and Bloomfield’s hellhounds started trailing him. Ward writes:

Michael was making a discovery that would stay with him from then on. He hated touring. Hated it. Eternally wired, he had suffered from insomnia for years. It would keep him up for days, and although he was enough of a pro to keep it from interfering with his playing, he didn’t like it at all.

In 1967, he quit. He created rock and blues group The Electric Flag later that year. They were hotly anticipated but failed to make the mark with their debut album, and by 1968 had dissolved. During this time Bloomfield’s marriage fell apart and he got hooked on smack, and descended into addiction. Around this time, Al Kooper called him to play on Super Session, a jam album. It would elevate him to rock stardom, but he dismissed it as a “scam.”

***

Engrossed in a junkie lifestyle, Bloomfield quit playing in 1970. His mother, Dottie Shinderman, sought out B.B. King, who wrote a letter and called Michael to sort him out. Bloomfield said: “My God, the next time I had a chance to see B.B. King, I was embarrassed to face this man who had meant so much to me. I so much wanted to be like him, play like him, and like he knew that I didn’t want to.” The feeling of admiration was reciprocal. King told Ward he considered Bloomfield his “son” who helped his career by getting him heard by a white audience. “That’s the kind of guy he was,” King concluded. “No telling what he might have accomplished if he’d lived longer, that’s how talented he was. I miss him.”

Throughout the 1970s Bloomfield took on projects with friends, cut cheaply-recorded records, and stayed reclusive in his San Francisco home. Being away from the limelight kept his hellhounds at bay, as he told Ward in 1973:

I used to be a very crazy guy, and I had pain almost every day for years and years and years. It never stopped. I don’t know if you’ve ever been crazy or ever really lost your mind to the degree that you hurt every day, physical, man, so that you would do anything to stop it. Now that is a distant memory.

During the same interview, he told Ward of his dissatisfaction:

I hear music and think of it in my mind, and I know how I want to hear it. All these sonorities and all the sounds everyone is capable of, and I live it all, in a way. It all comes through the radio, man. It all comes from the air, you know, and it all feeds into me. I think I know the sonorities and the melodies and the chords that are really beautiful, that you would find really beautiful and that most anyone would. I would like to put out a record that had those sounds on it. And I will. Oh, if I could only do just one that would make me as proud as the Beatles probably were with Sgt. Pepper or Jimi Hendrix was with Axis or I was with the first Butterfield album.

Ward remarks: “He thought I didn’t hear the pain in his voice, that I missed him brushing tears from his eyes. He was wrong.”

Ward explores Bloomfield’s fragile mental health in detail. His father suffered from depression, and the family had a history of suicide. In 1979, Bloomfield entered a state mental hospital to come off Placidyl, a hypnotic prescription drug he used to replace heroin. You get the impression mental illness was the biggest hellhound on his trail.

Toward the end of his life, Ward describes how a distressed Bloomfield became an alcoholic. His friend Norman Dayron had stopped spending time with him at this point. “I couldn’t stand it, and I felt very guilty about it because I felt as his friend I should take care of him,” he said. “But he wouldn’t let anybody take care of him.”

As a biographer, Ward successfully conveys the complex story of a troubled Jew, who could shake a string like no one else. The book is short and impassioned, and recounts the downfall of a man who, aged 24, told Rolling Stone: “Without a guitar, I’m like a poet with no hands.”

On Feb. 15, 1981, he was found slumped in a car in San Francisco. His corpse had no ID and was registered as a John Doe. The cause of death was cocaine and methamphetamine poisoning. Ward admits he can’t answer the questions about what happened; how he got there; why there were methamphetamines in his system (he avoided them); and why he was in a part of town where he knew no one. For Ward, none of that matters. All that matters is Bloomfield’s legacy. He concludes: “All we know is that Michael Bloomfield found sleep for the last time and, perhaps, as he left this Earth, heard the hellhounds’ baying receding into the darkness.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Ben Lazarus is a British journalist. He tweets at @BLazarus1.