Heirs to the Throne

In a new book, Robert Alter examines the debt American literature owes to the King James Bible

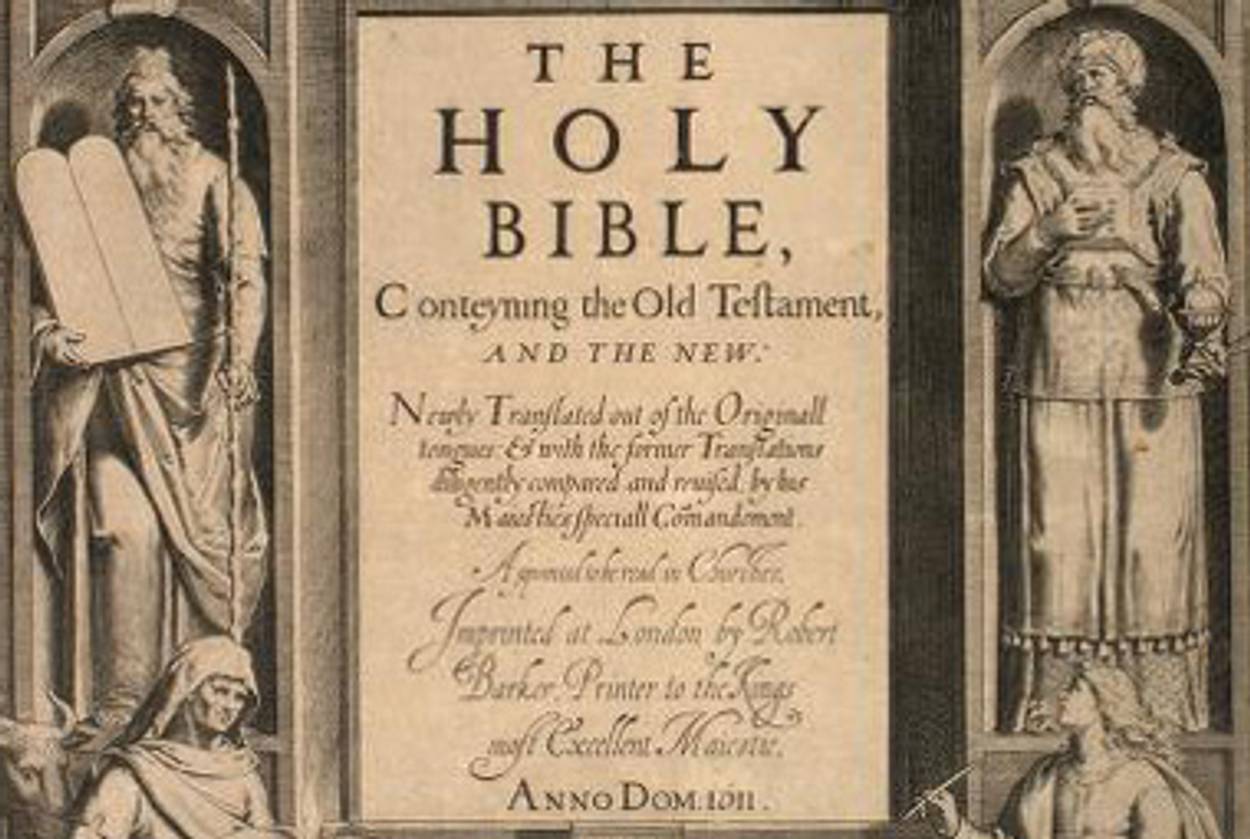

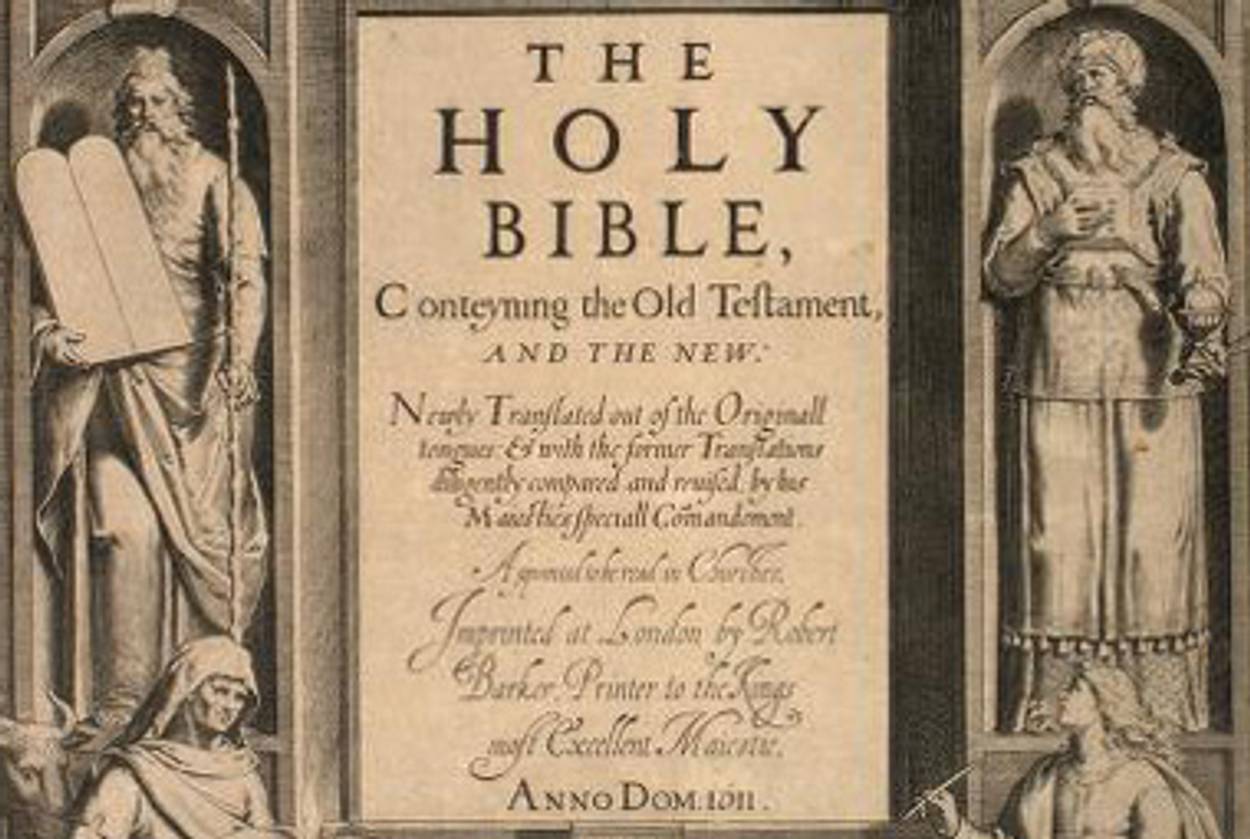

Historically speaking, America and the King James Bible are almost twins. The first English colony in North America was established at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607; four years later, the Church of England completed its translation of the Authorized Version of the Bible, which, like the colony, bore the name of the reigning monarch. And it is safe to say that, for the next 300 years at least, just about every English-speaking American grew up knowing the King James Bible better than any other book. As Robert Alter puts it in his new study Pen of Iron: American Prose and the King James Bible, America, even more than England itself, was affected by a “biblicizing impulse”: “It was in America that the potential of the 1611 translation to determine the foundational language and symbolic imagery of a whole culture was most fully realized.”

The English settlers were Christians, of course, but it was the Old Testament, much more than the New, that spoke to them and their experience. In the story of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt and conquest of the Promised Land, the Puritans found an obvious parallel to their own journey across the Atlantic and their struggle in the New World. (As Alter notes, Israelite place names are everywhere in the American landscape, from Salem to Shiloh.) The King James Bible, then, was not just the matrix of the American language, but the means of transmitting Jewish history, and the morality of the Hebrew Bible, to the American people.

As a leading scholar and translator of the Bible, who is also deeply knowledgeable about American literature, Robert Alter is ideally suited to study this complicated inheritance. Alter’s own translations of scripture—most recently, the Book of Psalms—have inevitably been measured against the familiar cadences of the King James Bible, and they can be seen in part as attempts to criticize or displace that standard text. But in literary terms, Alter recognizes, the King James version—though it may be “often inaccurate”—is canonical and irreplaceable. In a sense, the English Bible has ceased to be a translation and become a second original. If you were more mystically inclined than Alter, you could consider it an example of Walter Benjamin’s theory of translation, which holds that every true translation completes the meaning of a text as it appears in the mind of God.

The locutions of the King James Bible echo through our literature so pervasively that we often take them for granted. The Gettysburg Address offers a small but telling example. Why, Alter asks, did Lincoln begin by saying “Four score and seven years ago,” rather than just “eighty-seven years ago”? The answer is that he was drawing, perhaps unconsciously, on the phrase “three score and ten,” which appears 111 times in the King James Bible. By measuring time in this formal, archaic fashion, Lincoln raises American history to the same level as sacred history. At the end of the Address, Lincoln again turns to the Bible: When he promises that American democracy “shall not perish from the earth,” he is echoing a phrase from Job and Jeremiah.

At the core of Pen of Iron—the title, of course, is itself a Biblical allusion (“the sin of Judah is written with a pen of iron, and with the point of a diamond”—Jeremiah 17:1)—is Alter’s analysis of the Bible’s influence on three great American novels: Moby-Dick; Absalom, Absalom; and Seize the Day. In discussing these books, Alter shows that that influence cannot be measured strictly in allusions or verbal echoes. Melville, Faulkner, and Bellow do not simply use biblical language, they think in biblical categories—especially, Alter argues, when they are challenging the faith and morality that the Bible teaches.

Moby-Dick is a perfect case in point. Melville’s novel is a riot of language, whose lavish rhetoric owes a great deal to Shakespeare, Milton, and other 17th-century writers. But the elemental power and metaphysical scope of the novel are rooted in its complex response to the Bible. When the Pequod sets sail, for instance, Melville writes: “ever and anon, as the old craft dived deep in the green seas, and sent the shivering frost all over her, and the winds howled, and the cordage rang.” This simple form of narration, where events are connected only by “and,” is known as parataxis, and it is the Bible’s favorite technique: “Then Jacob gave Esau bread and drink, and rose up, and went his way: thus Esau despised his birthright.” (As Alter points out, the parataxis is still more pronounced in the Hebrew: The King James’s “then” and “thus” actually translate the Hebrew “and.”) Biblical parallelism, too, is used to heighten Melville’s style. When he writes that the sea is “worse than the Persian host who murdered his own guests; sparing now the creatures which itself hath spawned,” Alter observes that “the two long clauses … could almost be read as two lines of Biblical poetry.”

The irony is that Melville uses these biblical tropes in constructing a book that is a kind of anti-Bible—a long refutation of the existence of God and the goodness of Creation. In one of the best sections of Pen of Iron, Alter focuses on Melville’s use of Leviathan, the biblical sea-monster, as a way of turning scripture against itself. Leviathan, who is of course a prototype of Moby Dick, seems to Melville to puncture the Bible’s own chronology:

Who can show a pedigree like Leviathan? Ahab’s harpoon had shed blood older than Pharaoh’s. Methusaleh seems a schoolboy. I look round to shake hands with Shem. I am horror-struck at this antemosaic, unsourced existence of the unspeakable horrors of the whale, which, having been before all time, must needs exist after all humane ages are over.

Leviathan, as the principle of brute violence and evil, is older than the biblical dispensation (“antemosaic”) and will survive it. As Alter writes, the whale “drops the bottom out of history, leaving man as an inconsequential and transient mote in a play of cosmic energies that vastly antedates him and that will no doubt outlast him.” In this way, Melville uses the Bible to herald a new, post-biblical worldview—which is one reason why his echoes of the King James text are so starkly powerful.

Alter’s other subjects, Faulkner and Bellow, are also powerful prose stylists, but they are less directly indebted to the English Bible. The style of Absalom, Absalom, with its nonce words, Latinisms, involved syntax, and general fanciness, is as unlike the plainness of the Authorized Version as English can well be. Yet as Faulkner’s title announces, the novel’s plot is based on events from the life of King David—the rape of Tamar, the murder of Amnon, and the rebellion of Absalom. More, Alter writes, Faulkner builds the book around certain primal words that come straight from the King James Bible: “birthright, curse, land or earth, name and lineage … seed, birthplace, inheritance, house, flesh and blood … dust and clay.”

Pen of Iron makes a convincing case that it is impossible to fully appreciate American literature without knowing the King James Bible—indeed, without knowing it almost instinctively, the way generations of Americans used to know it. The problem is that, over the course of the last century, biblical literacy has plummeted, even as translations and editions of the Bible have proliferated. (Several free apps can put the whole King James Bible, along with many other versions, on your iPhone.) It would be interesting to try to read more recent American fiction through Alter’s lens: Can you hear the Bible in David Foster Wallace’s prose, or Lydia Davis’? “The essential point for the history of our literature,” Alter writes at the end of Pen of Iron, “is that the resonant language and the arresting vision of the canonical text, however oldentime they may be, continue to ring in cultural memory.” I wonder how faint the ring can grow before we stop hearing it completely.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.