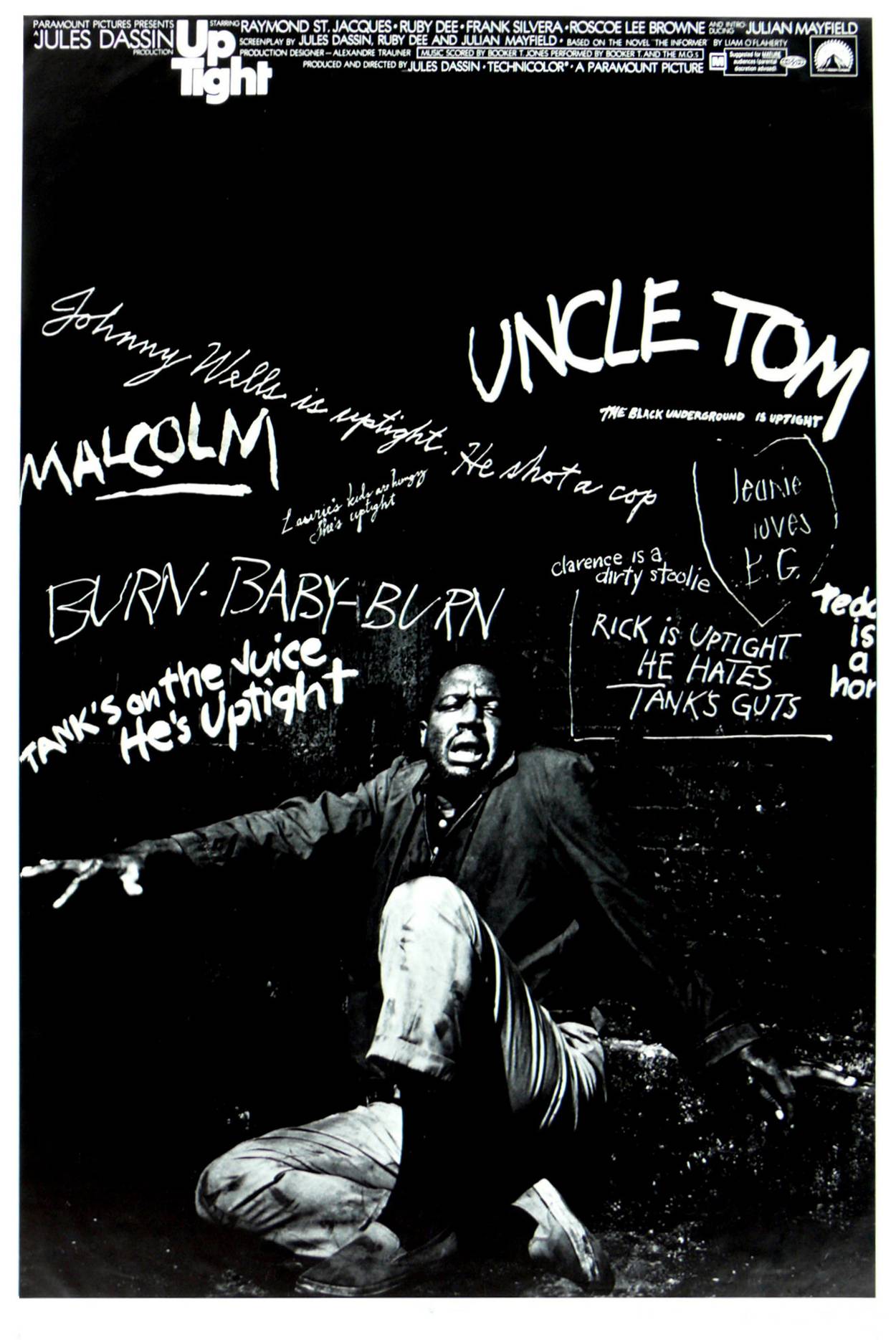

Uptight

Black History Month: Jules Dassin’s militantly Black 1968 movie echoes American social tumult today

Racial violence roils a Rust Belt city where an unemployed steelworker seeks self-obliteration even as an underground army battles an occupying police force. At once dated and topical, Jules Dassin’s echt 1968 Uptight depicts a fiasco and was one—at least at the box office.

Before Judas and the Black Messiah, a year in advance of the murder of activist Fred Hampton that is the subject of Shaka King’s new movie, there was Uptight. Made by the only member of the Yiddish “proletariat theater,” Artef, to become a big-shot, albeit blacklisted, Hollywood director, this bruising film maudit was the most deeply Red movie produced in Hollywood since the dawn of the Cold War. In addition to Dassin (1911-2008), Uptight is heavy on former communists and fellow travelers. Even the title sequence is by blacklisted animators, Faith and John Hubley.

More to the point, Uptight was also the most militantly Black movie of the 1960s. As the headline for a New York Times production story read, “‘It’s Gonna Blow Whitey’s Mind.’”

Uptight is predicated on conflicts between Black and white, integrationists and separatists, the Old Left and the New. A pure product of its moment, the film manifests American social tumult and Hollywood’s confusion; its title, sometimes rendered as two words followed by an exclamation point, was suggested by cast member Ruby Dee who, along with another ex-Red, Julian Mayfield, revised Dassin’s screenplay.

Dassin wanted to call the movie Betrayal, apt name for his Hollywood homecoming. An up-and-coming director in the 1940s, best known for his neorealist policier The Naked City (1948), Dassin was named as a communist before the House Un-American Activities Committee and blacklisted in 1950. Resuming his career in Europe, he directed the classic French heist film Rififi (1955) and, working in Greece, concocted the ultimate happy hooker comedy, Never on Sunday (1960), a movie whose sprightly theme popularized the misirlou at countless weddings and bar mitzvahs.

Groping for the new youthful audience and mindful of Bonnie and Clyde’s surprise success—a violent Depression Era gangster story beloved by the kids!?—the brains at Paramount Pictures conceived a remake of The Informer (1935), John Ford and Dudley Nichol’s adaptation of the bestseller by Liam O’Flaherty. A founder of Ireland’s Communist Party, O’Flaherty was one more free-floating radical; however steeped in Irish culture, his psychologically charged account of the brutish IRA renegade Gypo Nolan’s journey to the end of the night, pursued through foggy Dublin slums by his own demons as well as ruthless former comrades, after he sells out his closest associate to the police, could easily be imagined as a late-19th-century Russian novella.

Ford’s wildly atmospheric, much celebrated adaptation (presented with multiple Oscars including ones for Ford, Nichols, and Victor McLaglen as the hapless oxlike Gypo) was characterized by a domestic German Expressionism. Thus The Informer scored a unique trifecta—praised by aesthetes, certified by the industry, and championed by leftists. (“The Informer is about the closest Hollywood will ever come to producing a film with living human beings in it,” New Masses opined.) What better property to remake and who better to direct it than a certified ’30s Red turned European “artiste”?

‘Uptight’ was the most militantly Black movie of the 1960s. As the headline for a ‘New York Times’ production story read, ‘It’s Gonna Blow Whitey’s Mind.’

Dassin, back in the United States to direct the Broadway musical version of Never on Sunday, took the bait but switched the premise. Rather than student radicals, he stipulated that the movie deal with a group of Black Panther-like revolutionaries. Harking back to The Naked City, which had included extensive footage of the Lower East Side, Dassin planned to shoot on location, this time in Harlem, the neighborhood in which he grew up. New York was not hospitable however and for reasons likely connected to the recent election of Cleveland’s first Black mayor, Carl Stokes, the production relocated to that city’s African American ghetto, Hough.

Two months before the shoot opened, Dassin went to Atlanta to document the scene outside the Ebenezer Baptist Church following the funeral of Martin Luther King. The trauma of King’s assassination haunts the film, which was in a constant state of revision even once production began in June 1968, shortly after the killing of Robert Kennedy. Despair rules. Nonviolence is denounced as a nonstarter. King’s murder precipitates the movie’s tragic events—driving the Gypo Nolan character, Tank, to drink. Subsequently rejected by his former comrades, he informs on his best friend Johnny, sought by police for shooting the night watchman in the robbery of a Cleveland ammunition depot.

Dassin originally wanted James Earl Jones (the future voice of Darth Vader) to play Tank; when Jones proved unavailable he cast Mayfield in the role. Hardly a novice, Mayfield had acted on Broadway in the early 1950s (among other things replacing Sidney Poitier in the Kurt Weill-Maxwell Anderson musical Lost in the Stars). Mayfield was a less imposing presence than Jones, but his interpretation of Tank, a role he reworked for himself, gives the film an element of psychodrama. So does screenwriter (and Cleveland native) Ruby Dee’s searing portrayal of Tank’s girlfriend, Laurie, driven to prostitution to support her children.

Dee was not only a leading Black actress but a left-wing stalwart who played an angel in the all-blacklisted off-off-Broadway original production of The World of Sholom Aleichem. Mayfield was a produced playwright and published novelist, as well as a public intellectual whose political journey had taken him from the Harlem-based group around Paul Robeson that also included Dee (along with her husband Ossie Davis, Harry Belafonte, Lorraine Hansberry, and novelist John Oliver Killens) to revolutionary Cuba and newly independent Ghana.

Most controversially, Mayfield had defended Robert F. Williams, the North Carolina NAACP leader who advocated armed resistance to the Ku Klux Klan, most notably in the April 1961 issue of Commentary, alongside a symposium on “Jewishness & the Younger Intellectuals,” among them Philip Roth. Mayfield’s piece, “Challenge to Negro Leadership: The Case of Robert Williams,” ends by predicting that a “purely legalistic” approach to civil rights would prove insufficient: “Then to the fore may come Robert Williams, and other young men and women like him, who have concluded that the only way to win a revolution is to be a revolutionary.”

That in a sentence is the attitude that Mayfield, who left the CP in 1956, deeming it too reformist, brought to Uptight.

Liam O’Flaherty’s anti-hero informs on his comrade in the novel’s second chapter. In the Ford-Nichols movie, Gypo goes to the police in the first reel. Tank, by contrast, needs nearly half of Uptight before he betrays his friend.

The prelude allows for considerable political discussion and multiple viewpoints, principally those of the imperious radical leader B.G. (Raymond St. Jacques, fresh from appearing as the sole African American in John Wayne’s Vietnam movie The Green Berets) and the moderate politician Kyle (the Jamaican actor Frank Silvera, another leftist as well as Mayfield’s drama coach).

B.G., a junior-high-school teacher who affects a Nehru suit, has utter contempt for befuddled Tank, his background as a union organizer notwithstanding; another key confrontation has B.G. effectively expel an erstwhile white ally Teddy (Michael Baseleon), identified by his horn-rimmed glasses as an intellectual if not a Jew. Even here there is a divergence of opinion, with another, gentler member of the cadre urging Teddy to educate “the white brother.” For his part, B.G. nastily suggests that the only way Teddy can help the struggle is by supplying the group with guns. (Hard to watch this scene without speculating on the way that Dassin and Mayfield and Dee may have negotiated the screenplay.)

Other points of view are articulated by the welfare mom Laurie and professional stool pigeon Clarence (played with typically aristocratic aplomb by Roscoe Lee Browne). Uptight is not exactly Brechtian but, however stilted, it is a movie of ideas. Not until Michael Schultz’s Carwash or Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing would the Black community have a so programmatically polyphonous Hollywood movie. It’s significant that Gypo’s original cri de coeur, “I didn’t know what I was doin’,” is modified in the movie to Tank’s more existential question, “can anyone tell me why I did it?”—thus throwing the nature of his betrayal back to the audience.

Dassin’s trademark is a form of theatrical neorealism. Locations are inherently allegorical. The movie also employs a number of blatantly expressionist devices, notably a spinning camera and a scene largely reflected in a fun-house mirror. Not talk but action was Dassin’s forte. In one set piece, an entire neighborhood housed around a courtyard in a manner suggesting the worker’s domiciles in Eisenstein’s Strike witnesses Johnny shot down by police and proceeds to rain garbage on the cops.

Effectively restaging the drunken party scenes that won McLaglen his Oscar, Uptight builds a sense of bottled rage that explodes like a Molotov cocktail in the movie’s apocalyptic final reel—a manhunt closer through the slag heaps of Cleveland that evokes the dénouements of The Naked City and Dassin’s most formally accomplished movie Night and the City.

Paramount scarcely knew how to promote Uptight. In desperation, the studio recruited SNCC chairman and Black Power militant H. Rap Brown to explicate a preview screening at a Greenwich Village movie house. Their strategy went awry when members of the youthful audience accused the movie of being insufficiently revolutionary and a delegation of radical documentary filmmakers disrupted the post-screening press conference by smuggling a projector into the balcony and illuminating the stage with a newsreel on the real Black Panthers.

Critics were racially polarized. Uptight found cautious support from the Black mainstream—“the anger of black people has never been dealt with by the film industry, but in this picture, that anger is there,” noted the Amsterdam News—but only there. New York Times reviewer Vincent Canby was an exception to the general outrage. His observation that Dassin’s “intense and furious” movie was more than entertainment—the “sizable black audience responded almost as if it were at a revival meeting”—prompted a rebuttal from the paper’s lead critic Renata Adler. Something similar happened with the CP’s Daily World: An initial notice thought Uptight would “add more knowledge about the black world”; a second review warned that the movie was designed to “intensify the racist fears held by whites.”

Shell-shocked Dassin had long since announced that he would never make another movie in America; Paramount attempted to cut its losses in the spring of 1969 by rereleasing Uptight on a double bill with another failed “new wave” experiment, Otto Preminger’s bizarre LSD comedy Skidoo, which featured Groucho Marx as a gangster known as God. Uptight’s most successful element was the score provided by the Memphis soul band Booker T. and the MGs. The movie’s incongruously upbeat theme would be the band’s biggest hit and has enjoyed a long life as a radio “sound bed.”

Indeed, while writing this piece, I heard “Time is Tight” thus used on All Things Considered. However it might have been buried in 1969, Uptight (which can be streamed via iTunes, Vudu, Criterion, and Amazon) is still news.

J. Hoberman was the longtime Village Voice film critic. He is the author, co-author, or editor of 12 books, including Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds and, with Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting.