The Holocaust Play That Helped the Roman Catholic Church Reject Anti-Semitism

‘The Deputy,’ staged in West Berlin in 1963, was the first German drama to take on the horrors of the Holocaust and Pope Pius XII’s moral failures in World War II

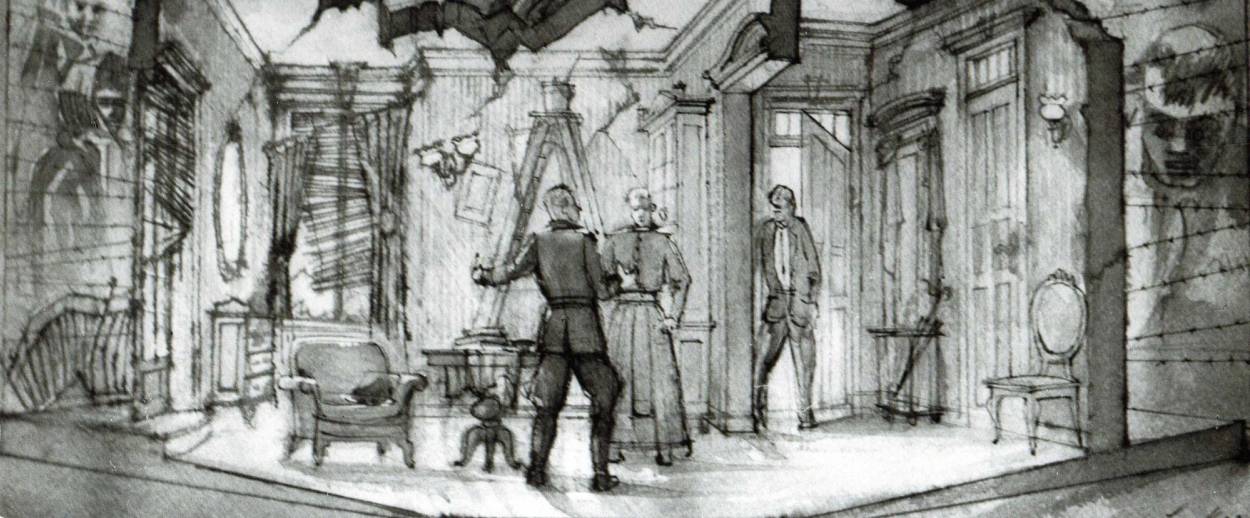

The Deputy, a blistering attack on Pope Pius XII’s response to the Holocaust, was the first major German work to openly address the question of the country’s complicity in the Holocaust. In the play, the heroic character Father Riccardo declares, “A deputy of Christ who sees these things and nonetheless permits reasons of state to seal his lips … that pope is a criminal.” Authored by Rolf Hochhuth, an unknown 31-year-old playwright who had belonged to the Hitler Youth, the play was brought to the stage by its legendary and by then elderly director, Erwin Piscator, and Leo Kerz, a Jewish refugee and The Deputy’s costume and set designer. It premiered in 1963 at West Berlin’s Freie Voklsbühne Theater.

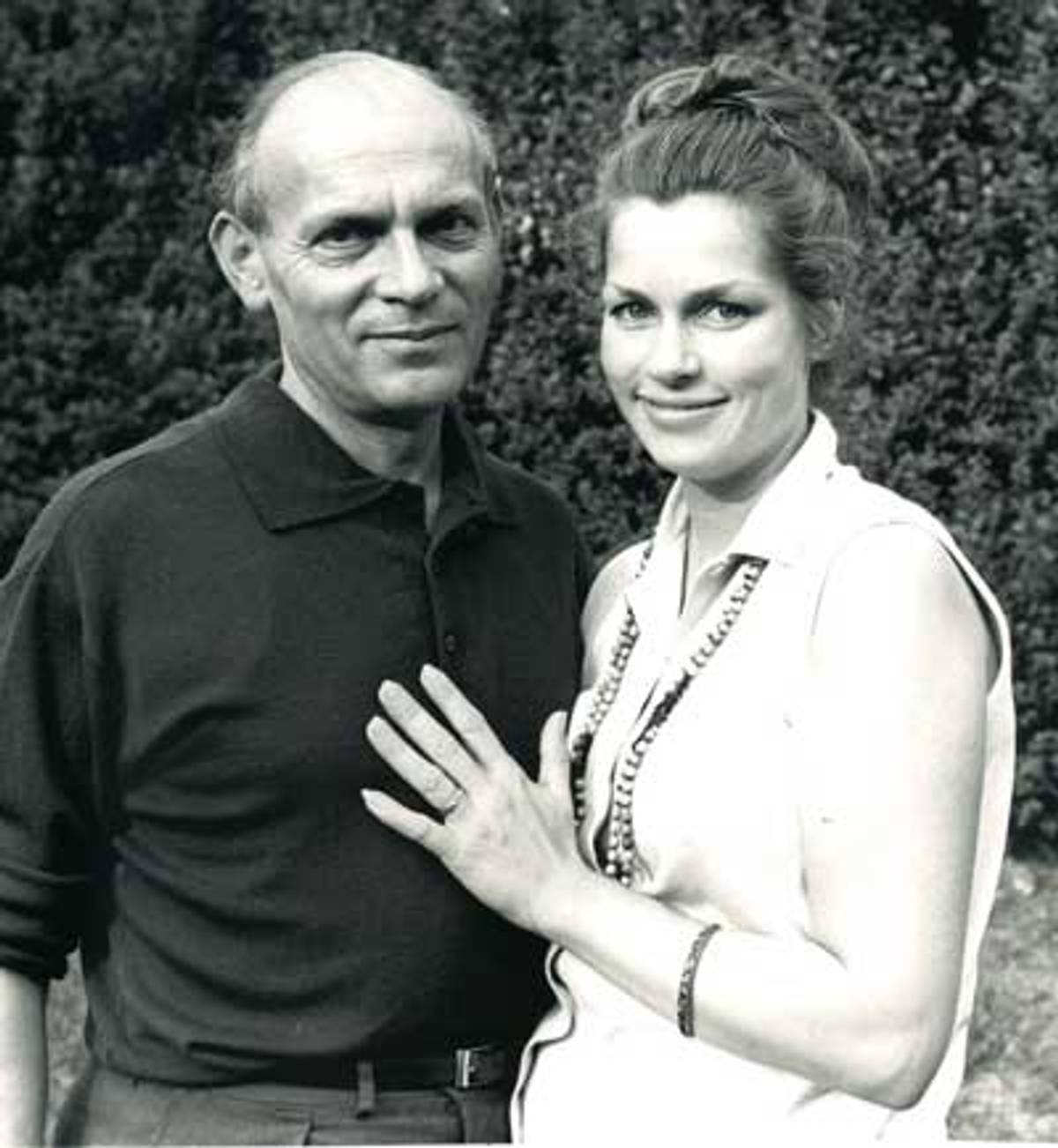

Curious about the play’s genesis and reception, I recently interviewed Louise Hirschfeld, Kerz’s wife. Her husband, a Jew in left-wing German theater, had fled Berlin in 1936, eventually settling in the United States. His family remained behind and perished at Sobibor. I wondered what it had been like for Kerz to be back in Germany only 18 years after the war’s end, staging a major and controversial Holocaust work.

The force behind the staging of The Deputy, Hirschfeld said, was Erwin Piscator. By the early 1960s, the famed director who had delighted and shocked Weimar Germans with his left-wing politics and technological innovations had, in Kerz’s words, come to be regarded as “The Grand Old Man who had outlived himself.” Piscator disagreed. Believing that it was the artist’s responsibility to confront the Holocaust, he decided to produce The Deputy. The moment was favorable: A year earlier, the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, reported around the world, had stirred interest in the Holocaust.

Assembling his team, Piscator wrote to Kerz, his former student, in New York. “I need you here to design a play by an author who has not written for the stage before. … You will see yourself that the subject matter has to be treated delicately.” Without hesitation, Kerz accepted.

In the winter of ’62 Hirschfeld and her husband arrived in West Berlin, a city encircled by parallel concrete and barbed-wire fences, the beginnings of the Berlin Wall. Avoiding the city’s center, they rented a refurbished chalet in the Gruenwald suburb. “There were bullet holes in every other building surrounding us,” Hirschfeld recalled. Queried as to how her husband dealt with these constant reminders of the war, she answered, “He just threw himself into his work.”

Kerz had years of experience to draw on having worked for CBS TV, Broadway, and the Metropolitan Opera. Still, The Deputy had its singular challenges. “Don’t forget the play was eight hours long,” Hirschfeld commented. “He had to read that. And as things were cut, it was reduced to five and then to three hours, he had to redo the sets.”

Using photographs, Kerz designed huge and haunting concentration-camp murals. He had eschewed abstract and modern designs, favored by Piscator, for realism. “He couldn’t do something that used contemporary art or covered something up,” remembered Hirschfeld. After all, he was the one member of the production team directly connected to the Holocaust. “When I saw them,” Hirschfeld recalled, “I knew that his emotions were on full-force.”

One morning, Kerz arrived at the theater and discovered that the stage painters had their own sense of reality. “I’ll never forget it,” Hirschfeld stated, “murals of Jewish prisoners, all with hooked noses, like the kind of terrible anti-Semitic drawings that existed during the Nazi period.” Kerz exploded; why hadn’t they followed his drawings? Confused and exasperated, they retorted “but they are Jews.” He fired back, “Well, I am Jewish and I don’t have that kind of nose.”

Consumed by the myriad production tasks, long intense work days, and occasional disagreements, The Deputy’s team failed to fully appreciate that outside the theater walls, controversy was mounting daily. “I don’t think they were really prepared,” Hirschfeld surmised. “However, when the Krupp family and the Vatican sent lawyers to try and stop it, they started to realize that this was really explosive material.”

“I don’t think it would create such a stir today,” notes Rabbi A. James Rudin, author and former director of Interreligious Affairs at the American Jewish Committee. “But at the time, and I was a congregational rabbi in Illinois, it was an enormous debate. Pius was the pope for 19 years, through WWII and then 13 years after the war. So for many Catholics, he was the only pope they ever knew. He was ascetic, had a prayerful mode, lean, and very formidable. So for anybody to criticize him, in any way, came as a shock. And then to criticize him for perceived inaction or worse during WWII, that came as an even greater shock.”

Just weeks before the premiere, Father Hans Muller spoke before 5,000 West Berlin Catholics, urging them to fight this defamation. But Catholics, a small percentage of Berlin’s population, were hardly the only outraged Germans. For while Pius may have failed to respond with adequate moral force to the Holocaust, it was not the pope but Nazi Germany that had initiated, planned, and executed these monstrous crimes. Germans who preferred that this past remained buried understood that The Deputy, in a loud and public fashion, would raise uncomfortable questions. The play broke “the loud silence” of the 1950s when Holocaust discussion was avoided, explained Dr. Erika Fischer-Lichte, professor of theater at the Freie Universitate Berlin. A student at the time, she attended three performances. “The Deputy,” she notes, “marks the beginning of a process that was long overdue.”

***

On Feb. 20, 1963, after close to 12 months of tension-filled work, Kerz and his wife arrived at the theater for the premiere. Standing outside were police in riot gear. If the cast and crew had been unsettled by the police and demonstrators, by the end of the evening they had their reward. “Piscator, Hochhuth, and Kerz, all stood on stage holding hands to thunderous ovations,” recalled Hirschfeld. There was good reason to celebrate that evening. But Kerz skipped the cast party, opting for a quiet night with his wife and Robert Lackenbach, an American photographer. “He wanted to be with Americans,” Hirschfeld stated.

During their stay in Germany, they had lived in Berlin, without ever being of the city. Once, while driving, Kerz looked out at the multitude of shiny Mercedes and Volkswagens, turned to his wife and scoffed, “Oh, sometimes I really feel like just ramming right into them.” Outside of work, Kerz had had little contact with “them”—Germans—for their social orbit had been a group of American journalists, what Hirschfeld called “their rock.”

Yet alienation and anger, while clearly present, were never strong enough to erase Kerz’s German identity. Hirschfeld is certain that her husband’s decision to join The Deputy’s crew was based in part on a desire to reconcile with his homeland. As a child and young man in Berlin he had, in her words, “lived in a large world.” A bundle of talent; Kerz had been like a firecracker that could explode in multiple directions. He played the violin at the age of 4, participated in gymnastics and boxing, thought of becoming a conductor, studied watercolor with the famed painter Paul Klee, and later design with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, one of the city’s most respected stage designers. “I think,” his wife noted, “it was difficult to separate from all that.”

Shortly after The Deputy’s premiere, Kerz and his wife returned to New York. Kerz had completed his work but the life of the play had just begun. It opened in cities across Western Europe. In Paris, Archbishop Cardinal Feltin denounced the play as “useless accusations and sterile polemics.” Unwittingly he helped to put it on the front page of the city’s daily papers and ticket sales exploded. On opening night, angry theatergoers hurled protest pamphlets from the balcony. In Basel, the theater received bomb threats, while in Vienna verbal altercations between the play’s supporters and detractors became so raucous that the police were called in to restore order.

The situation was the same in the United States. New York City Mayor Robert Wagner was flooded with letters urging him to revoke the Brooks Atkinson Theater’s license. Producer Herman Shumlin, citing the “deep antagonism” toward the play, offered his cast members an unconditional release from their contracts. They all stayed. Opening night, protesters paraded with signs, “Bigots Enjoy The Deputy” and “Shumlin is a Bigot.”

The protests were not the entire story. Dr. Albert Schweitzer, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, viewed The Deputy as “a solemn warning to our culture admonishing us to forgo our acceptance of inhumanity.” Walter Kerr, prominent New York drama critic and American Catholic, despite finding The Deputy void of artistic merit, wrote, “Without the play, we might not have looked into ourselves, and the looking—in my opinion, for what it is worth—is due, salutary and already profitable.”

A notable cleric who “looked in” was German Bishop Josef Stangl. In 1964, when the Second Vatican Council reached an impasse regarding the rejection of the deicide charge, the belief that the Jews were collectively responsible and thus damned for killing Christ, Stangl realized he could not remain silent. Speaking to his fellow clerics, he recalled the controversy and pain The Deputy had produced in his German homeland. He concluded with a challenge: Addressing the councilmen as “Deputies of the Lord,” he urged them to issue a message of “truth not tactics.”

“Stangl’s moving address broke the ice,” wrote historian Michael Phayer. “The Council Fathers moved ahead with deliberations on Nostra Aetate. A German bishop had made a significant contribution to reversing the church’s anti-Semitism.”

Leo Kerz died in 1976, after decades of notable and award-winning work in both the American and German theater. His wife notes that he had always been careful in selecting his projects, always wanting to do serious productions. In selecting The Deputy, he chose wisely.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Charlotte Bonelli is the author of Exit Berlin.