Home Alone

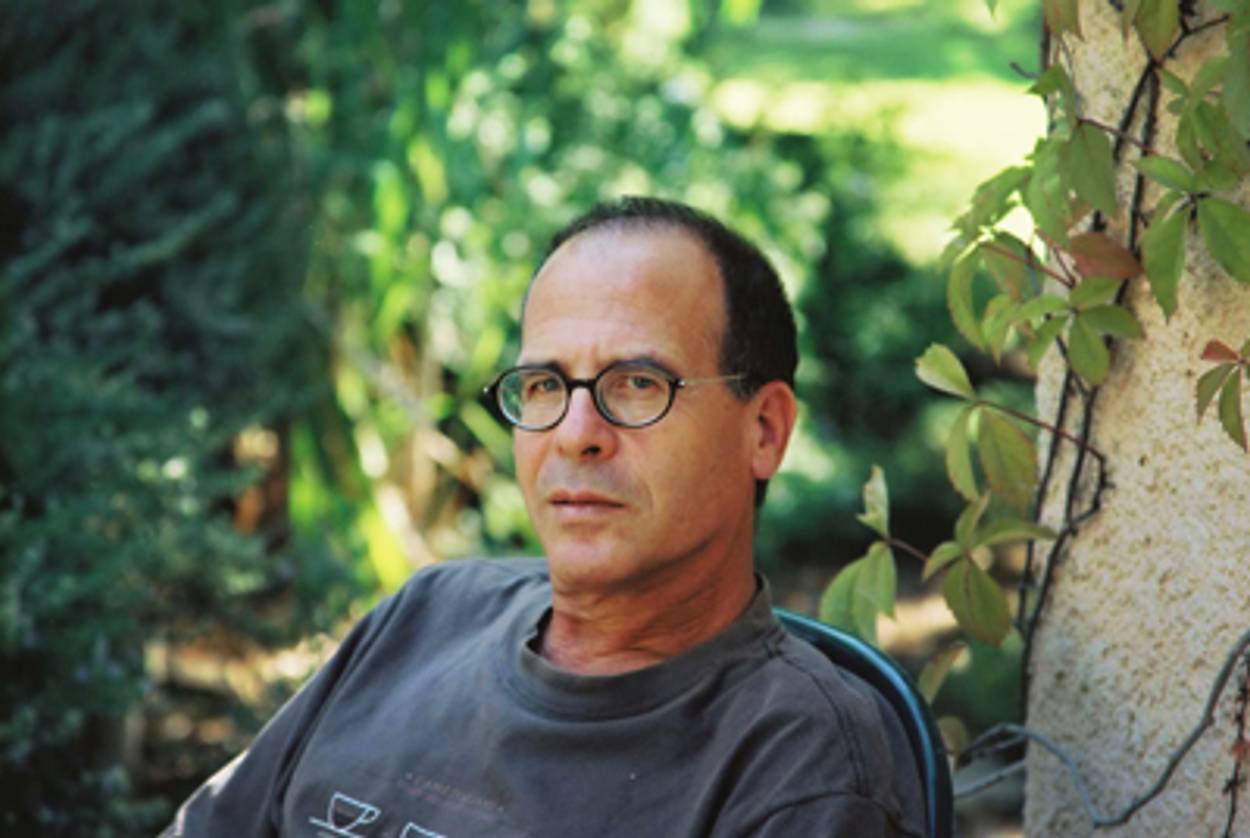

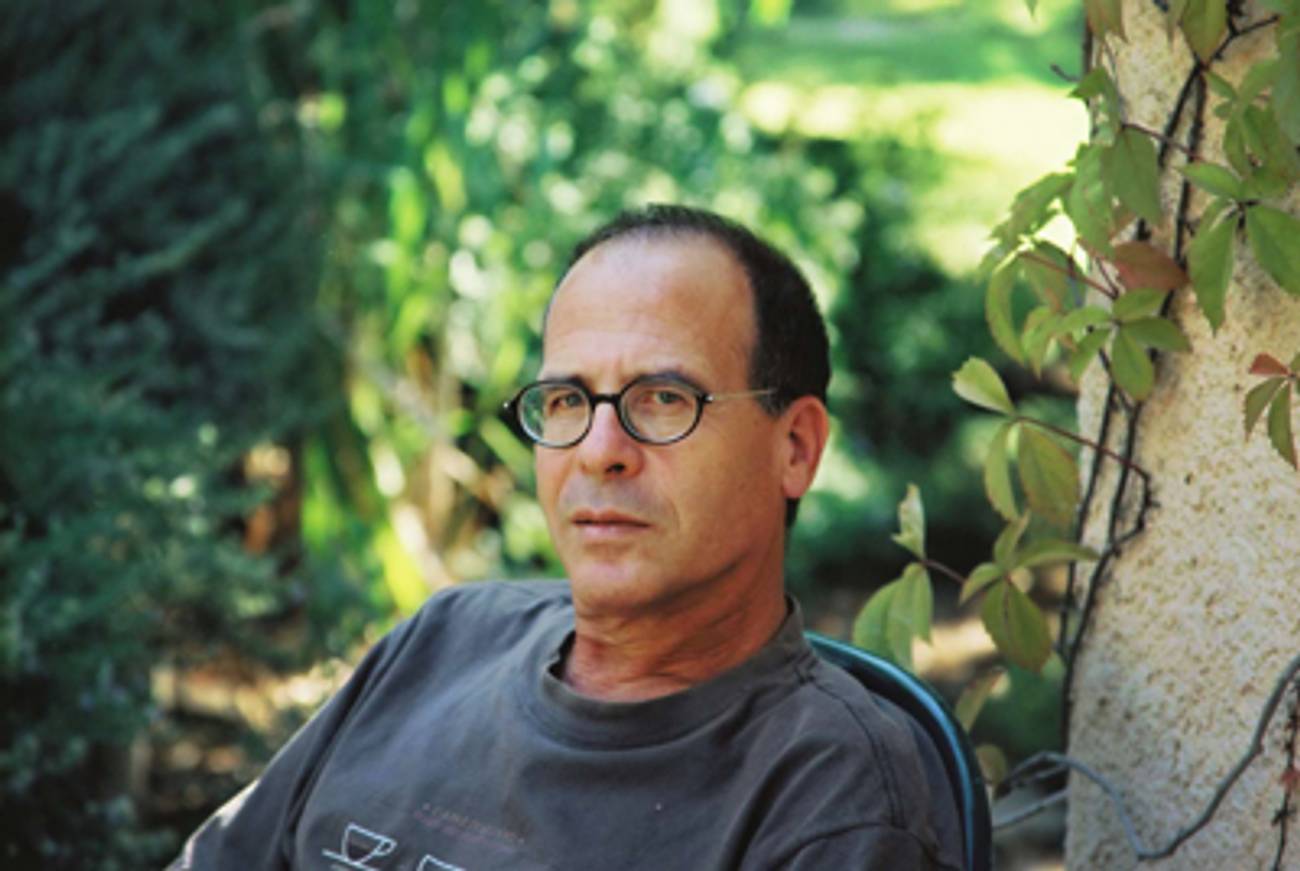

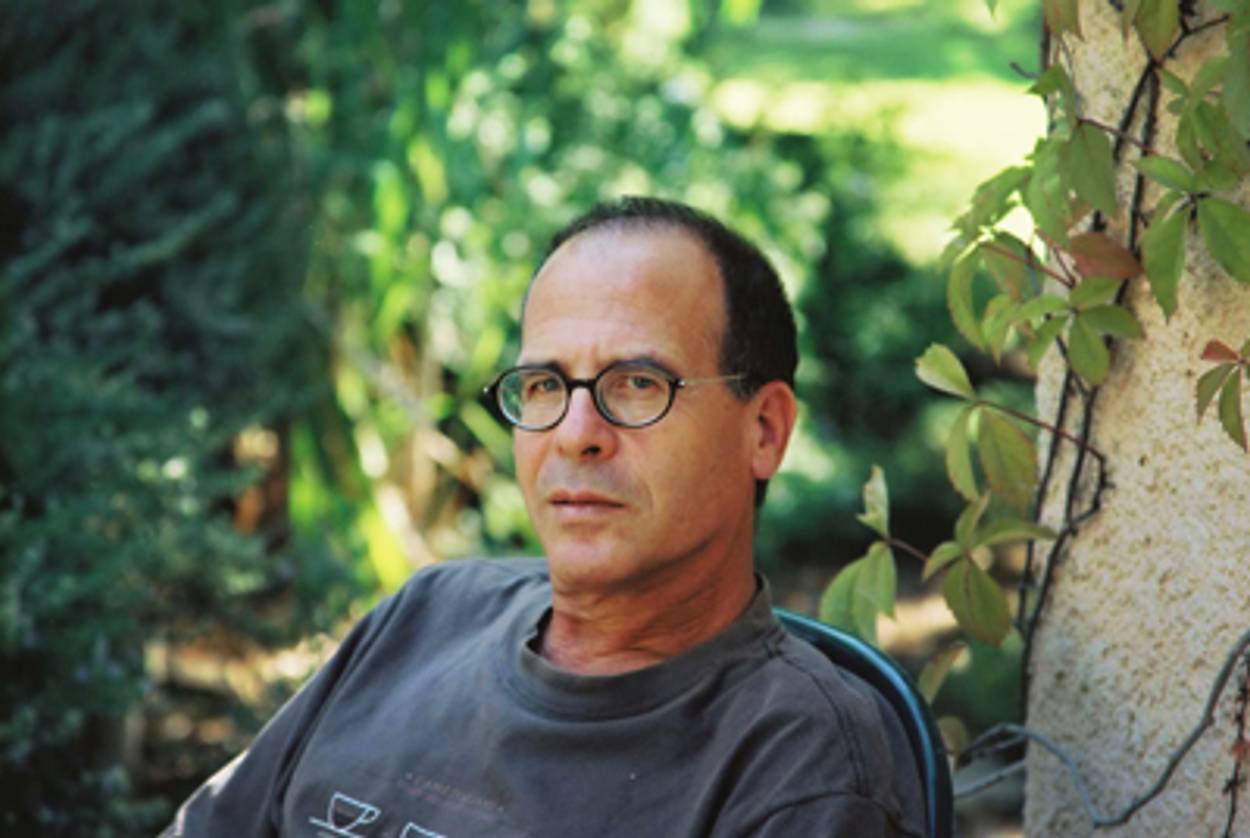

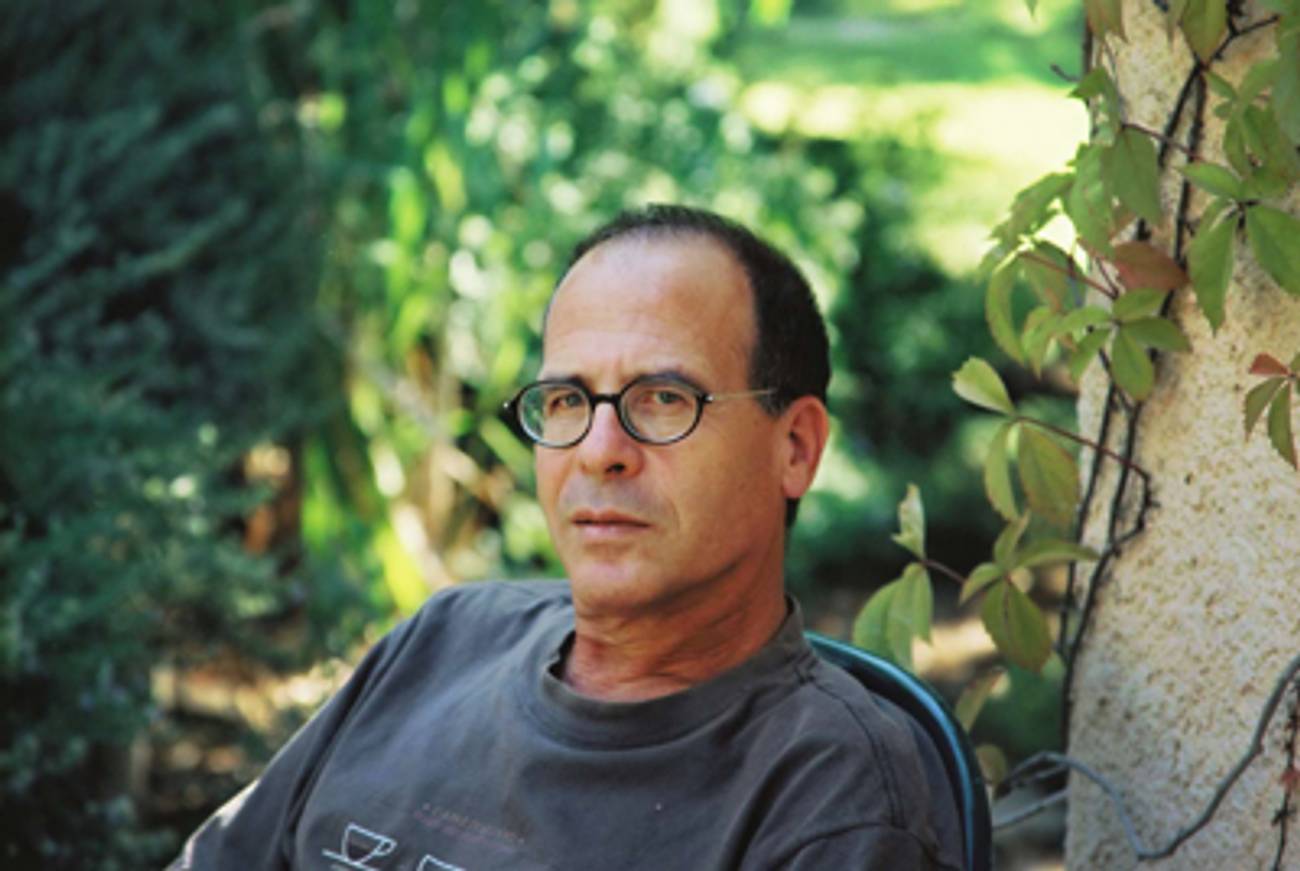

Meir Shalev holds forth on pigeons, homeland, and why reading a book is like a blind date

A Pigeon and a Boy, the new novel by Israeli author Meir Shalev, tells two stories, the first about a pair of teenagers—a boy nicknamed “the Baby” and his great love, a girl from Tel Aviv—who train pigeons as messengers for the Haganah. The second story follows Yair Mendelsohn, a tour guide, as he takes a group of American dignitaries to a monastery near Jerusalem, the site of a battle during the 1948 War of Independence in which one of the visitors had fought. Conceived during that war, Yair is now middle aged and unhappily married when, with a gift from his dying mother, he embarks on a journey to find a home of his own.

Shalev, the grandson of early settlers, was also born during the 1948 war. A regular columnist for the daily Yediot Ahronot, he has written five previous novels, three works of nonfiction, and numerous books for children; his works, translated into more than twenty languages, have been best sellers in Israel, Holland, and Germany. Last year, A Pigeon and a Boy won the Brenner Prize, Israel’s highest literary honor.

With its emphasis on pigeons and the idea of home, the novel is symbolically very rich. Which came first in your mind, the characters or the symbols?

I did not have pigeons in mind when I started to write my book. I started to describe Yair Mendelsohn, who gets this gift of money from his mother. I started to describe the relationships of Yair, his mother, and Tirzah, his female contractor.

Then I thought of using the pigeons as a symbol of loving one’s home. So I started to read a little bit about pigeons, and I met an archaeologist and historian who is a great expert on the history of pigeons in Israel, from the time we used them as poor little sacrifices in the Temple. He also knew a lot about the homing pigeons of the Haganah and the Palmach. I was curious, and he sent me to some old pigeon handlers. When I started to talk to them and heard some stories, I realized that there is much more in the homing pigeon idea than a symbol for the love of home. And I thought, I will finish this novel about Yair and his house, and this will be one book. Then I will write a love story about two pigeon handlers, and how they used the pigeons to send love letters to each other, and so on. But then one day, as if from nowhere, this idea of how to join them—that later became the last letter the Baby sends to his girlfriend—just landed on my window. It was very exciting.

Dr. Laufer, a veterinarian and the primary pigeon trainer in the novel, gives a moving speech when he visits the kibbutz where the Baby lives. He quotes a poem by Hayyim Nahman Bialik, who used the pigeon as a symbol of the Jewish people coming back to their homeland.

It is the Prophet Isaiah who said that after the destruction, we will come back to our land like pigeons returning. But pigeons are symbolic in other respects as well. They are a symbol of love and marriage—which is, by the way, a false symbol. Pigeons may “marry” for life, but there are a lot of infidelities in the pigeon loft. The other symbol, of course, is as the bird of peace, which is also false, because pigeons are very quarrelsome. They have terrible fights among themselves, and males may injure and even kill each other. I think the symbol was created because of the story of the flood in the Bible, where Noah sent the pigeons from the ark to see if the water had receded. So it became a messenger of good news.

In the novel there is a certain repetition of images and phrases that bring to mind a fairy tale. Is that something you do deliberately?

I think it happens consciously. Many of the stories I heard as a child were the stories from my grandparents about their lives and history, and those resembled fairy tales. I always knew that they didn’t tell the truth, that they added something to make the story more appealing. Most of the writers of my family come from my father’s side. But the storytellers of my family come from my mother’s side. They were farmers, and when they were telling me a story about their childhood in Russia, about their first day in Palestine, about the family characters I never knew, it always sounded like a fairy tale.

Yair’s women are quite powerful in shaping his life: His mother inspires and pays for his home, his girlfriend, Tirzah, renovates it as his contractor, his wife, Liora, a real estate mogul, employs and controls him. Why is that?

I wanted to portray a man who is passive. But I have these kind of women in my other books as well. In The Blue Mountain, in Esau, I have women who are strong characters, very influential. They are not like the Jewish mother from American literature who sits, nesting on her son and is overprotective and has something to say about everything. I have mothers who do not bother their children, but they are very strong and have influence on their lives by mere personality and integrity.

And of course, in a way, it has to do with my own mother and some other feminine characters in my family. I always had a closeness to the women of my family. We have men in my family who are taller and bigger, but I look like the women: small framed and dark. My mother, my sister, my daughter, my aunt, and my grandmother—all women who are related to me—in a way, look like me. So I felt this kind of affiliation since I was a little boy.

Yair’s mother has a list of what every person needs; a home and a story top her list. If you draw out her idea, you can argue that everyone needs a homeland and a national literature. Jews come from one of the oldest traditions in the world and yet the country of Israel is very young. How does this make you think about your literary history?

Even though Israel is very young, we still have a very long literary history that starts with the Bible. We even write the same language, and what’s so astonishing about this is that I can read texts that were written three or four thousand years ago. This is something that does not exist in any other language. If King David came to visit Jerusalem today, he could read my book and understand most of it. So even though Israel is very young, we have the longest history today on Earth of written literature in one language.

So Biblical literature forms an Israeli national literature?

Yes. For example, in my first book, The Blue Mountain, I described the pioneers of the second Aliyah who came to Palestine from East Europe and Russia. Of course, this is something that did not exist in Biblical time; it’s a new phase of the history of the Jews. But still, it’s the same land, the same country, the same language. Many of the seekers even relate to the fact that they speak this language and use Biblical expressions. So I really feel this sense of being one writer in a very, very long line of writers who started this profession so many years ago.

Yet you often get pegged as a “magical realist,” and put into a category of international writers that includes Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Salman Rushdie.

I don’t call it “magical realism” because that is a theory created by people who research and study literature. And naturally, they have this tendency to divide literature into categories because, while doing so, they feel so much more scientific.

I think it has to do with one’s imagination. We write fiction. We even call it—in English, at least—“fiction.” So things that are described in novels are not necessarily true, and they do not have to obey laws of physics and chemistry. There are two things that writers must know how to use: memory and imagination. And we all know that memory is not something we can trust. It keeps changing all the time, as if by itself. And it doesn’t work in linear mode. It’s a very jumpy, surprising process of ideas. And then there is imagination, which is, by definition, uncontrollable. My work is to give it some kind of a meaningful pattern in a book. So I don’t call it “magical realism”; it’s just my imagination.

That’s probably a welcome comment to readers who may not be fans of the genre.

Look, each of us should know what he likes in literature. You don’t have to finish a book—even if it’s my book, I will not be insulted. I look at reading a book as a blind date, and you know after, say, twenty minutes if this blind date is good for you or bad for you. So it’s possible to leave a book after forty pages. You simply say, “You are very good, I am very good, but we are not a good couple together, and I will find myself another book to read.”

So what writers have you formed long-term relationships with?

My parents were both teachers, and my father was a Bible scholar and a poet. They insisted that we children read only good books. And this is what they said, “good books.” They didn’t censor us by saying, “Don’t read this. It’s for grownups.” They always said, “Don’t read this. It’s a badly written book” or “Read this, it’s a beautifully written book.” My father gave me Lolita to read when I was fourteen years old, when it was just translated to Hebrew.

I love the Russian writers, Gogol, Mikhail Bulgakov, and, of course, Vladimir Nabokov. And in America, it is Mark Twain and Melville. As a young man, I also liked very much the works of Thoreau. He gave me many answers and, in a way, some peace of mind. As a matter of fact, the first time I came to the United States, when I was twenty-five, the first thing I did was drive all the way to New England to see Walden Pond and then go to New Bedford and Nantucket. It was like a pilgrimage for me.

A few years ago when Mario Vargas Llosa was speaking in New York, he suggested that quality literature is rarely produced by writers living in peaceful countries. Do you think an artist needs political turmoil to create good art?

Yeah, maybe. I live in a non‑peaceful country, and I am not able to write anywhere else. In my career I have been generously offered places to write, in England, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, the United States. People and organizations have said, “Come to us. Sit here. You won’t be bothered by the Israeli news. Write your literature here peacefully for half a year, a year, or even more.” And I never did it, because I cannot write outside of Israel. I need my language, my atmosphere, even though it’s not a very relaxing atmosphere. I feel I lose my powers when I leave my place and my country. So maybe Llosa is right in saying this. But then I can think about writers who wrote in a very peaceful manner. Thomas Mann wrote some very beautiful literature in a peaceful time, living a very relaxed, peaceful existence. So it is not necessarily the truth for everybody.